Excerpted below is a Quora discussion with illuminating commentary from Aaron Brown, former asset risk manager. AB responds to Topic Question and related comments, text in italics with my bolds and added images.

Excerpted below is a Quora discussion with illuminating commentary from Aaron Brown, former asset risk manager. AB responds to Topic Question and related comments, text in italics with my bolds and added images.

Quora? What will make conservatives accept climate change as real science?

AB: There are scientists who study cloud formation, ocean currents, rainfall patterns and other aspects of climate. Some are good, some not so much. Most people, liberal or conservative, accept that much of this is science.

Then there are scientists who build climate models and make predictions about things like global average temperature from 2081 to 2100 under different assumptions about human emissions and other factors. The people doing this work are considered scientists, but the conclusions are not science in the sense of empirically verifiable facts or consensus theories with strong empirical confirmation.

It’s a semantic game whether you call the conclusions “science” or not, but either way they are not as certain as scientific laws about gravity or momentum. People who like the predictions will embrace them, people who don’t like the predictions will resist them.

Liberals tend to be open to new ideas, conservatives tend to be more skeptical. That means many liberals are more willing to take strong action based on model predictions than are most conservatives. Skeptics tend to accept models if they make useful, non-obvious predictions that turn out to be true. Unfortunately it will take at least a century to gather that kind of evidence for climate models.

One possible breakthrough would be improvements in forecasting weather. You can prove a weather model in months rather than decades or centuries. But the fundamental claim of climate science is that it’s easier to predict global decadal averages in fifty years than next month’s weather in New York’s Central Park. That kind of claim—”I can’t predict the stuff you can check but trust me on stuff you can’t check”—makes skeptics skeptical.

A more likely breakthrough would be the the people making climate predictions proving their modeling ability by making useful, non-obvious predictions in other fields that can be validated. So far we have not seen this—successful modelers in other fields moving to climate science, or climate modelers proving success in other fields. This is a major point of skepticism for skeptics.

Finally, many conservatives are skeptical due to the big money involved in climate change combined with intense government interest and possibilities for vast wealth from subsidies and other programs. This is called Big Science and it’s often been dead wrong in the past, not to mention occasionally threatening all life on Earth. There are some successes of Big Science as well but skeptics will note the temptation to skew climate science for money or to push policies the advocates wanted before any climate support showed up.

None of this is relevant for policy decisions. If we somehow knew for certain today what the global mean temperature would be from 2081 – 2100, it wouldn’t tell us whether it was a good idea to ban coal or impose a carbon tax today. Conservatives are apt to assume any legislation will be written by lobbyists paid by cronies and empire-building bureaucrats rather than any kind of scientist. The laws will have unintended consequences, and send the economy and technology down unpredictable novel paths. We can’t estimate the effect on the human environmental footprint, we have only limited ability to relate the human environmental footprint to climate, and even less to relate climate to human welfare.

In such circumstances, the conservative inclination is to wait until you’re sure you’re helping things before spending a lot of money and writing a bunch of rules. The liberal tendency is to use your best judgement today, and expand the stuff that works tomorrow, while fixing or abandoning the stuff that doesn’t. This choice has nothing to do with climate science.

Comment: A model is just a theory put into numbers.

AB: Agreed, but the problem is lack of data. You can’t check 80 year in the future predictions with 30 years of data; and the global climate is so complex you need far more data even than we have with current measurements.

The data from more than 150 years or so is local data averaged over centuries or longer, useless for predicting global shorter-term data. Prior to 1990 we have very noisy data that is broader and available daily or sometimes even more often, but only since 1990 do we have anything like reliable, consistent global data.

People do calibrate their models to be consistent with the past, sometimes with more success than others. But there are so many parameters to global climate that this is not a useful check.

Comment: The required accuracy of your data and models grows exponentially with the amount of time you are predicting. It’s practically impossible to improve weather models beyond a certain point, so it’s not fair to consider this a failing of climate science.

AB: This is the central claim of climate science, but it remains unproven. Chaotic systems are not inherently unpredictable—for example the multibody solar system—and three or more bodies under gravity are chaotic—appears to have remained stable and pretty easy to predict for billions of years.

Attempts to predict weather in the most straightforward way, breaking the atmosphere down into small parts and applying rules of physics, have not succeeded in precise or long-range predictions—but there clearly are weather patterns that repeat often enough they must have some explanation. Modern weather prediction relies mainly on observed regularities without firm theoretic explanations.

You may be right that weather prediction will always be intractable, but perhaps some out-of-the-box idea will change that. If it did, we’d probably understand a lot more about climate.

It’s not obvious that long-term averages are more stable and predictable than shorter-term ones. In the stock market, for example, prices are pretty close to a random walk and uncertainty increases pretty steadily with the square root of time interval.

If you look at actual temperature measurements over local areas or global, over time scales from days to millions of years, uncertainty seems to increase with time, but slower than the square root. The unit of most certainty seems to be a year—predicting the average temperature over the next year has less uncertainty than predicting tomorrow’s temperature, but also less uncertainty than predicting the average temperature over the next decade or century.

Trajectories of a double pendulum. The simple predictable behavior of a pendulum appears chaotic when a second pendulum is attached. How many factors interact in our climate system?

This is a pure statistical observation, ignoring all climate science. The claim of climate science is models that incorporate things like solar variation, volcanoes, human emissions and so forth can make long-range averages less uncertain than annual averages. But we’ll need a lot of examples of long-range predictions—centuries of data—to confirm that directly, without resorting to climate theory; meaning that’s unlikely to convince skeptics in this century.

Of course you’re right that there seem to be physical limits that cause climate to move in cycles rather than drifting off to entirely new regimes—but regimes do change, and on planets other than Earth perhaps to extremes like losing the atmosphere.

Long exposure of double pendulum exhibiting chaotic motion (tracked with an LED)

But conservation of energy, for example, does not necessarily impose a constraint. There are many ways for energy to be removed from or added to global temperatures. It’s not necessarily true that, say, reducing incoming solar radiation cools the planet. In a simple system, reducing heat input lowers temperature. But in a complex system you could touch off any number of positive and negative feedback effects that could lead to any outcome.

Comment: I think this group is under valuing the large amount of research that has been predicting increases in global temperatures and the effects it will cause. There is ample data on the rate of increase in green house gases [CO2 and Methane] caused by humans lately.

AB: Are you saying that the predictions will convince skeptics? I disagree for several reasons.

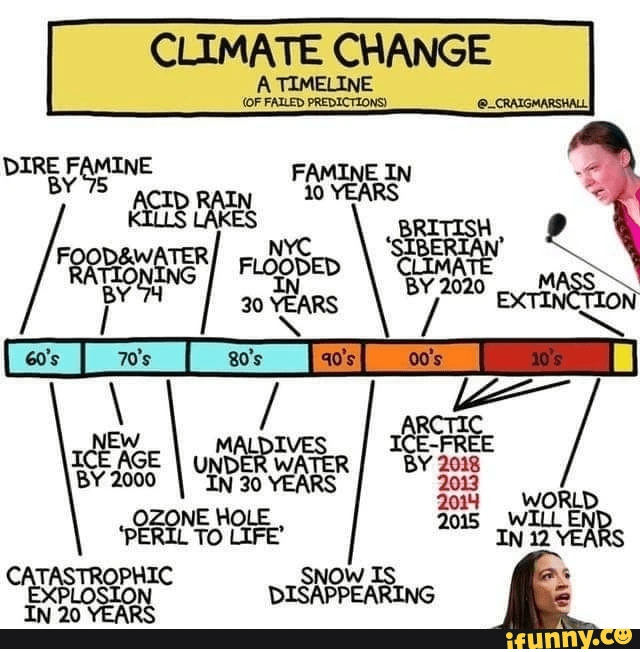

1. There have been many predictions, many of which were spectacularly wrong, none of which were spectacularly right. The more catastrophic the prediction, the more often it turned out to be spectacularly wrong. Now you can go back after-the-fact and say the people making the worst predictions were nuts and other people made predictions that were not spectacularly wrong, but skeptics will find this unconvincing—like someone sifting through horoscope predictions to find some that seemed to come true.

2. The more sober predictions have merely been extrapolations of the recent past, too obvious to convince skeptics. Every time anything happens lots of people claim to have predicted it, and that it will continue in the future until disaster. Skeptics think that if temperatures started falling tomorrow, the predictions would quickly shift to predicting global cooling.

3. Yes, atmospheric CO2 levels have gone up, and those could cause temperature increases, and humans are emitting CO2, and there’s no other obvious explanation for the increases in CO2. But those are simple observations. To convince skeptics of your explanations and predictions, you have to do more. If temperature increases tracked CO2 increases—rather than CO2 going up steadily and temperature bouncing up and down with more down months than up months—but an overall increase, the connection is not obvious.

4. Videos like the one you posted that tell us what things will be like decades in the future, something we cannot check, will not convince skeptics.

I think I outlined the main things likely to convince skeptics in my answer.

Comment: Many of the inter related factors determining climate have non linear relationships so modeling is extremely challenging and in order to produce sensible sounding outputs, tuning software is used to produce an answer deemed politically correct. If funding agencies would ban the use of tuning software the model funding would soon stop because of the self evident garbage answers.

AB: I agree and would go even further. I think climate is chaotic, and cannot be usefully modeled.

Everyone agrees that weather is chaotic, so only tentative short-term predictions are useful. But the defining claim of climate science is that if you average parameters like temperature over the entire globe over 20-year periods, it becomes predictable.

But if you check that assumption by comparing the standard deviation of temperature changes over larger regions and longer periods, you see it hits a minimum at single locations over one year. You can predict the average temperature in Central Park over the next year more accurately than tomorrow’s average temperature over New York State, or 20-years’ average temperature in Central Park.

It’s possible that casual models driven entirely by physics could surmount that issue, but so far these have been entirely unsuccessful without statistical tuning—tuning that does not improve ability for future predictions. Moreover you would expect such a model to predict weather better than climate, and no models can do that—they can only claim successful predictions over periods too long for practical testing.

That doesn’t mean climate models are worthless, but they are less reliable than weather reports, not more reliable.

Comment: In the case of climate, it’s the case that a large chunk of conservatives are still conservationists, who don’t get counted as environmentalists because of the heavy left (Marxist, even) bent of the green movement over the last several decades. Why not appeal to this perspective?

AB: I think you’re focusing on the wrong issue. You don’t have to convince anyone that protecting the environment is important, you have to convince them you have a plan that will do more good than harm.

Nuclear power is a great example. It reduces CO2, but also other forms of pollution. It doesn’t require decades and trillions of dollars to build a new power-grid infrastructure, it’s plug-and-play with the existing system (almost, anyway). The technology is well-understood, safe and efficient. You won’t find opposition from conservatives, only from some liberals.

But other tactics will require more argument. A carbon tax, for example, would send technology and the economy down an entirely new path, with entirely unpredictable consequences. It would seem to increase uncertainty about future climate rather than decrease it. It has other issues as well. To gain support for one from skeptics, you’ll have to convince them that you can predict the effects of such a tax on human welfare in 2100 well enough to make it a good bet.

Geoengineering is the cheapest and surest way to reduce global temperatures, but it controversial on both left and right for its possible unintended consequences. Here you have to convince people the gain is worth the risk.

The single best no-brainer solution is to work for world peace and cooperation. War is the biggest threat to the environment and climate. Solutions to climate change and dozens of equally consequential global issues will require cooperation—or at least less conflict—among nations. Redirecting military spending to climate research and mitigation would do tremendous good. Best of all, world peace and global cooperation have many direct advantages, not just vastly improving our ability to respond rationally to issues like climate change.

One comment