Progressively Scaring the World (Lewin book synopsis)

Bernie Lewin has written a thorough history explaining a series of environmental scares building up to the current obsession with global warming/climate change. The story is enlightening to people like me who were not paying attention when much of this activity was going down, prior to Copenhagen COP in my case. It also provides a rich description of happenings behind the scenes.

As Lewin explains, it is a particularly modern idea to scare the public with science, and thereby advance a policy agenda. The power of this approach is evident these days, but his book traces it back to more humble origins and describes the process bringing us to the present state of full-blown climate fear. It is a cautionary tale.

“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.”

― Edmund Burke (1729-1797)

This fearful belief evolved through a series of expanding scares as diagrammed below: This article provides only some highlights while the book exposes the maneuvers and the players, their interests and tactics. Quotes from Lewin appear in italics, with my titles, summaries and bolds.

This article provides only some highlights while the book exposes the maneuvers and the players, their interests and tactics. Quotes from Lewin appear in italics, with my titles, summaries and bolds.

In the Beginning: The DDT Scare

The Context

A new ‘environmentalism’ arose through a broadening of specific campaigns against environmental destruction and pollution. It began to target more generally the industries and technologies deemed inherently damaging. Two campaigns in particular facilitated this transition, as they came to face-up squarely against the dreams of a fantastic future delivered by unfettered sci-tech progress.

One of these challenged the idea that we would all soon be tearing through the sky and crossing vast oceans in just a few hours while riding our new supersonic jets. But even before the ‘Supersonic Transportation Program’ was announced in 1963, another campaign was already gathering unprecedented support. This brought into question the widely promoted idea that a newly invented class of chemicals could safely bring an end to so much disease and destruction—of agriculture, of forests, and of human health—through the elimination of entire populations of insects. Pg.16

When the huge DDT spraying programs began, the Sierra Club’s immediate concern was the impact on nature reserves. But then, as the movement against DDT developed, and as it became increasingly involved, it began to broaden its interest and transform. By the end of the 1960s it and other similar conservation organisations were leading the new environmentalism in a broader campaign against DDT and other technological threats to the environment. Pg.18

The Alarm

This transformation was facilitated by the publication of a single book that served to consolidate the case against the widespread and reckless use of organic pesticides: Silent Spring. The author, Rachel Carson, had published two popular books on ocean ecology and a number of essays on ecological themes before Silent Spring came out in 1962. As with those earlier publications, one of the undoubted contributions of the book was the education of the public in a scientific understanding of nature. Pg.18

We will never know how Carson would have responded to the complete ban on DDT in the USA. She was suffering from cancer while writing Silent Spring and died shortly after publication (leaving the royalties from its sale to the Sierra Club), but the ban was not achieved for another decade. What we do know is that a full ban was never her intention. She supported targeted poisoning programs in place of blanket spraying, and she urged the authorities to look for alternative and ‘integrated control’, along the lines of the ‘Integrated Pest Management’ approach that is common and accepted today. Pg.19

The Exaggeration

Overall, by today’s standards at least, Carson’s policy position was moderate, and so we should be careful not to attribute to her the excesses of her followers. The trouble with Carson was otherwise: it was in her use and abuse of science to invoke in her readers an overwhelming fear. In Silent Spring, scientific claims find dubious grounding in the evidence. Research findings are exaggerated, distorted and then merged with the purely anecdotal and the speculative, to great rhetorical effect. Pg.19

Historically, the most important area of distortion is in linking organic pesticides with human cancers. The scientific case for DDT as a carcinogen has never been strong and it certainly was not strong when Silent Spring was published. Of course, uncertainty remained, but Carson used the authority of science to go beyond uncertainty and present DDT as a dangerous carcinogen. And it was not just DDT; Carson depicts us ‘living in a sea of carcinogens’, mostly of our own making, and for which there is ‘no safe dose’. Pg.19

The Legacy

If we are to understand how the EPA ban came about, it is important to realise that this action succeeded in breaking a policy stalemate that was becoming increasingly hazardous for the increasingly embattled Nixon administration. On one side of this stalemate were the repeated scientific assessments pointing to a moderate position, while on the other side were calls for more and more extreme measures fuelled by more and more outrageous claims. Pg.21

Such sober assessments by scientific panels were futile in the face of the pseudo-scientific catastrophism that was driving the likes of the Audubon Society into a panic over the silencing of the birds. By the early 1970s two things were clear: public anxiety over DDT would not go away, and yet the policy crisis would not be resolved by heeding the recommendations of scientific committees. Instead, resolution came through the EPA, and the special role that it found for itself following the publication of the Sweeney report. Pg.22

Summary

The DDT scare demonstrated an effective method: Claim that a chemical pollutant is a serious public health risk, Cancer being the most alarming of all. The media stoked the fear, and politicians acted to quell anxiety despite the weak scientific case. Also, the precedent was set for a governmental entity (EPA in this case) to make a judgment overruling expert advice in responding to public opinion.

The SST Scare

The Context

The contribution to the demise of the SST of the environmentalists’ campaign is sometimes overstated, but that is of less concern to our story than the perception that this was their victory. While the DDT campaign was struggling to make headway, the SST campaign would be seen as an early symbolic triumph over unfettered technological progressivism. It provided an enormous boost to the new movement and helped to shape it. Back in 1967, the Sierra Club had first come out campaigning against the SST for the sonic shockwaves sweeping the (sparsely populated) wilderness over which it was then set to fly. But as they began to win that argument, tension was developing within the organisation, with some members wishing to take a stronger, more general and ethical stand against new and environmentally damaging technologies such as this. P.27

With popular support for environmental causes already blooming across the country, and with the SST program already in jeopardy, scientists finally gained their own position of prominence in the controversy when they introduced some new pollution concerns. . . If that wasn’t enough, environmental concerns were also raised in the most general and cursory terms about the aircraft’s exhaust emissions. These first expressions of pollution concerns would soon be followed by others, from scientists who were brought into the debate to air speculation about various atmospheric catastrophes that would ensue if these supersonic birds were ever allowed to fly. Pg.27

The Alarm

What did make the front page of the New York Times on 2 August 1970 was concern about another climatic effect highlighted in the executive summary of the report. The headline trumpeted ‘Scientists ask SST delay pending study of pollution’ (see Figure 2.1). The conference had analysed the effect of emissions from a fleet of 500 aircraft flying in the stratosphere, and concerns were raised that the emission of water vapour (and to a lesser extent other emissions) might absorb sunlight sufficiently to have a local or even global effect on climate. . . The climatic change argument remained in the arsenal of the anti-SST campaigners through to the end, but it was soon outgunned by much more dramatic claims about possible damage to the ozone layer. Pg.30

Throughout the 1970s, scientific speculation drove a series of ozone scares, each attracting significant press attention. These would climax in the mid-1980s, when evidence of ozone-depleting effects of spray-can propellants would be discovered in the most unlikely place. This takes us right up to the start of the global warming scare, presenting along the way many continuities and parallels. Indeed, the push for ozone protection up to the 1980s runs somewhat parallel with the global warming movement until the treaty process to mitigate ozone damage suddenly gained traction and became the very model for the process to mitigate global warming. The ozone story therefore warrants a much closer look. Pg.31

For Harold Johnston of the University of California, the real problem with SST exhaust would not be water vapour but oxides of nitrogen. Working all night, the next morning he presented Xerox copies of handwritten work projecting 10–90% depletion. In high traffic areas, there would be no stopping these voracious catalysts: the ozone layer would all but disappear within a couple of years. Even when Johnston later settled for a quotable reduction by half, there could be no quibbling over the dangers to nature and humanity of such massive environmental destruction. Pg.44

A New York Times reporter contacted Johnston to confirm his claims and although the report he delivered was subdued, the story remained alarming. It would take less than a year of full-fleet operations, Dr Johnston said in a telephone interview, for SSTs to deplete half of the stratospheric ozone that shields the earth from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Scientists argued in the SST debate last March that even a 1 percent reduction of ozone would increase radiation enough to cause an additional 10,000 cases of skin cancer a year in the United States. The next day, 19 May 1971, a strong negative vote demolished the funding bill. All but a few stalwarts agreed that one more vote in the House and it was all over for Boeing’s SST. After that final vote, on 30 May, the New York Times followed-up on its initial story with a feature on Johnston’s claims. This was written by their leading science writer, Walter Sullivan, an influential science communicator important to our story. Pg.48

The Exaggeration

It is true that in 1971 the link between skin cancer and sun exposure was fairly well established in various ways, including by epidemiological studies that found fair-skinned communities in low latitudes tended to record higher rates. However, the link to ultraviolet light exposure (specifically, the UV-B band) is strongest among those cancers that are most common but are also rarely lethal. The link with the rarer and most dangerous cancers, the malignant melanomas, is not so strong, especially because they often appear on skin that is not usually exposed to the sun. Pg.43

Thus, sceptics of the fuss over the risk of a few percent thinning of the already variable ozone layer would point out that the anti-SST crowd did not seemed overly worried about the modern preference for sunshine, which was, on the very same evidence, already presenting a risk many orders of magnitude greater: a small depletion in the ozone layer would be the equivalent of moving a few miles south. To the dismay of their environmentalist opponents, the bolder among these sceptics would recommend the same mitigation measures recommended to the lifestyle migrants—sunscreen, sunglasses and sunhats. Pg.43

But in 1971 there was no way to directly measure stratospheric NOx. No one was even sure whether there was any up there. Nor was there any way to confirm the presence—and, if so, the concentration— of many of the other possibly relevant reactive trace gases. This left scientists only guessing at natural concentrations, and for NOx, Johnston and others had done just that. These ‘best guesses’ were then the basis for modelling of the many possible reactions, the reaction rates, and the relative significance of each in the natural chemistry of the cold thin air miles above. All this speculation would then form the basis of further speculations about how the atmosphere might respond to the impacts of aircraft that had not yet flown; indeed none had even been built. Pg.46

The Legacy

But already the message had got through to where it mattered: to the chair of the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Science, Clinton Anderson. The senator accepted Johnston’s theory on the strength of Sullivan’s account, which he summarised in a letter to NASA before concluding that ‘we either need NOx-free engines or a ban on stratospheric flight’. And so it turned out that directly after the scrapping of the Boeing prototype, the overriding concern about supersonic exhaust pollution switched from water vapour to NOx. Pg.49

As startling as Johnston’s success appears, it is all the more extraordinary to consider how all the effort directed at solving the NOx problem was never distracted by a rising tide of doubt. The more the NOx effect was investigated, the more complex the chemistry seemed to be and the more doubtful became the original scientific foundations of the scare. In cases of serial uncertainty, the multiplying of best-guess estimates of an effect can shift one way and then the other as the science progresses. But this was never the case with NOx, nor with the SST-ozone scare generally. Pg.50

Summary

The SST Scare moved attention to the atmosphere and the notion of trace gases causing environmental damage, again linked to cancer risk. While ozone was the main issue, climate change was also raised along with interest in carbon dioxide emissions. Public policy was moved to withdraw funding for American SST production and later to ban European SSTs from landing in the US. It also demonstrated that fears could be promoted regarding a remote part of nature poorly known or understood. Models were built projecting fearful outcomes from small changes in atmospheric regions where data was mostly lacking.

The CFC Scare

The Context

Presumptions about the general state of a system’s stability are inevitable in situations of scant evidence, and they tend to determine positions across the sceptic/alarmist divide. Of course, one could suppose a stable system, in which a relatively minor compensatory adjustment might have an alarming impact on civilisation, like the rapid onset of a few metres of rise in sea level. But it is the use of such phrases as ‘disturbing the delicate balance of nature’ or ‘a threat to life on Earth’ that are giveaways to a supposition of instability. Hence Scorer’s incredulity regarding Johnston’s leap towards his catastrophic conclusion: ‘How could it be alleged seriously that the atmosphere would be upset by introducing a small quantity of the most commonly and easily formed compounds of the two elements which comprise 99% of it?’ Pg.68

Meanwhile, ‘Sherry’ Rowland at the University of California was looking around for a new interest. Since 1956 he had been mostly researching the chemistry of radioactive isotopes under funding from the Atomic Energy Commission. Hearing of Lovelock’s work, he was intrigued by the proposal that nearly all the CFCs ever produced might still be out there. Were there no environmental conditions anywhere that would degrade these chemicals? He handed the problem to his post-doctoral research assistant, Mario Molina. Molina eventually concluded that indeed there were no ‘sinks’ for CFCs anywhere in the ocean, soils or lower atmosphere. Thus we should expect that CFCs would drift around the globe, just as Lovelock had proposed, and that they would do so for decades, even centuries. . . or forever? Could mankind have created an organic compound that is so noble that it is almost immortal? Pg.75

The Alarm

The ozone effect that Molina had stumbled upon was different to those previously proposed from rockets and aeroplanes in one important respect: it would be tremendously delayed. Like a hidden cancer, the CFCs would build up quietly and insidiously in the lower atmosphere until their effect on the ozone miles above was eventually detectable, decades later. But when unequivocal evidence finally arrived to support the theory, it would be too late. By then there would be no stopping the destruction of the thin veil protecting us from the Sun’s carcinogenic rays. What Molina had stumbled upon had, in double-dose, one sure element of a good environmental scare. Pg.77

According to Walter Sullivan, they had calculated that spray-can CFCs have already accumulated sufficiently in the upper air to begin depleting the ozone that protects the earth from lethal ultraviolet radiation. On current emission trends, 30% of the ozone layer would be destroyed as early as 1994. This was no longer a story about saving the sky for our grandchildren. These scientists had found an effect, already in train, with ‘lethal’ consequences for all living things during the lifetime of most of the New York Times’ massive and influential readership. Pg.82

During 1988, the second wave of global environmentalism would reach its peak in the USA, with CFC pollution its first flagship cause. Mid-March saw the US Congress voting unanimously to ratify the Montreal Protocol. It was only the second country to do so, while resistance remained strong in Europe. The following day, NASA announced the results of a huge two-year study of global ozone trends. Pb.107

The new scientific evidence came from a re-analysis of the ozone record. This found that the protective layer over high-population areas in the midlatitudes of the northern hemisphere had been depleted by between 1.7% and 3% from 1969 to 1986. These trends had been calculated after removing the effect of ‘natural geophysical variables’ so as to better approximate the anthropogenic influence. As such, these losses across just 15 years were at much faster rates than expected by the previous modelling of the CFC effect. Pg.107

The statements of the scientists (at least as quoted) made it clear to the press that this panel of experts had interpreted the empirical evidence as showing that a generalised CFC-driven depletion had already begun, and at a much faster rate than expected from the modelling used to inform the Montreal Protocol. Pg.109

This linking by scientists of the breakup of the southern vortex with low ozone readings in southern Australia during December 1987 morphed into the idea that the ozone hole itself had moved over southern Australia. All sorts of further exaggerations and extrapolations ensued, including the idea of the hole’s continuing year-round presence. An indication of the strength of this mythology is provided by a small survey in 1999 of first-year students in an atmospheric science course at a university in Melbourne. This found that 80% of them believed the ozone hole to be over Australia, 97% believed it to be present during the summer and nearly 80% blamed ozone depletion for Australia’s high rate of skin cancer. Pg.114

After the London ‘Save the Ozone Layer Conference’, the campaign to save the ozone layer was all but won. It is true that a push for funding to assist poor country compliance did gain some momentum at this conference, and it was thought that this might stymie agreement, but promises of aid were soon extracted, and these opened the way for agreement on a complete global phase-out of CFC production. Pg.119

The Exaggeration

Here we had Harvard scientists suggesting that hairspray destruction of the ozone layer had already begun. Verification of the science behind this claim could not have played any part in the breaking of the scare, for there was nothing to show. It turned out that McElroy and Wofsy had not shown their work to anyone, anywhere. Indeed, the calculations they reported to Sullivan were only submitted for publication a few days after the story ran in the New York Times. By that time already, the science did not matter; when McElroy and Wofsy’s calculations finally appeared in print in February 1975, the response to the scare was in full swing, with spray-can boycotts, with ‘ban the can’ campaigns, and with bills to that effect on the table in Congress. Pg.82

It was on track to deliver its findings by April 1976 when it was hit with the shocking discovery of a new chlorine ‘sink’. On receiving this news, it descended into confusion and conflict and this made impossible the timely delivery of its much-anticipated report. The new ‘sink’ was chlorine nitrate. When chlorine reacts to form chlorine nitrate its attack on ozone is neutralised. It was not that chlorine nitrate had previously been ignored, but that it was previously considered very unstable. However, late in 1975 Rowland concluded it was actually quite stable in the mid-stratosphere, and therefore the two most feared ozone eaters—NOx and CFCs—would neutralise each other: not only could natural NOx moderate the CFC effect, but hairsprays and deodorants could serve to neutralise any damage Concorde might cause. Pg.84

Now, at the height of the spray-can scare, there was a shift back to climate. This was reinforced when others began to point to the greenhouse effect of CFCs. An amazing projection, which would appear prominently in the NAS report, was that CFCs alone would increase global mean temperature by 1°C by the end of the century—and that was only at current rates of emissions! In all this, McElroy was critical of Rowland (and others) for attempting to maintain the momentum of the scare by switching to climatic change as soon as doubts about the cancer scare emerged. It looked like the scientists were searching for a new scientific justification of the same policy outcome. Pg.87

The Legacy

The ban on the non-essential uses of spray-can CFCs that came into force in January 1978 marked a peak in the rolling ozone scares of the 1970s. Efforts to sustain the momentum and extend regulation to ‘essential’ spray cans, to refrigeration, and on to a complete ban, all failed. The tail-end of the SST-ozone scare had also petered out after the Franco-British consortium finally won the right to land their Concorde in New York State in 1977. And generally in the late 1970s, the environmental regulation movement was losing traction, with President Carter’s repeated proclamations of an environmental crisis becoming increasingly shrill (more on that below). Eventually, in 1981, Ronald Reagan’s arrival at the White House gave licence and drive to a backlash against environmental regulation that had been building throughout the 1970s. Long before Reagan’s arrival, it was made clear in various forums that further regulatory action on CFCs could only be premised on two things: international cooperation and empirical evidence. Pg.89

To some extent, the demand for better science had always been resisted. From the beginning, advocates conceded that direct and unequivocal evidence of CFC-caused depletion might be impossible to gain before it is too late. But concerns over whether the science was adequate went deeper. The predictions were based on simple models of a part of our world that was still remote and largely unknown. Pg.91

Summary.

The CFC scare brought the focus of dangerous behavior down from the stratosphere to spray cans in the hands of ordinary people, along with their use of air conditioners so essential to life in the sunny places people prefer. Speculation about ozone holes over polar regions were also more down to earth. And for the first time all of this concern produced an international treaty with extraordinary cooperation against CFCs, with UNEP soaring into prominence and gaining much credit for guiding the policy process.

The CO2 Scare

The Context

In the USA during the late 1970s, scientific interest in the potential catastrophic climatic consequences of carbon dioxide emissions came to surpass other climatic concerns. Most importantly, it came to surpass the competing scientific and popular anxiety over global cooling and its exacerbation by aerosol emissions. However, it was only during the late 1980s that the ‘carbon dioxide question’ broke out into the public discourse and transformed into the campaign to mitigate greenhouse warming. For more than a decade before the emergence of this widespread public concern, scientists were working on the question under generous government funding. Pg.122

The proven trigger for the release of funding was to forewarn of catastrophe, to generate public fear and so motivate administrators and politicians to fund investigations targeting the specific issue. The dilemma for the climatic research leadership was that calls for more research to assess the level of danger would fail unless declarations of danger were already spreading fear. Pg.143

The scare that would eventually triumph over all preceding global environmental scares, and the scare that would come to dominate climatic research funding, began with a coordinated, well-funded program of research into potentially catastrophic effects. It did so before there was any particular concern within the meteorological community about these effects, and before there was any significant public or political anxiety to drive it. It began in the midst of a debate over the relative merits of coal and nuclear energy production. Pg 144

The Alarm

In February 1979, at the first ever World Climate Conference, meteorologists would for the first time raise a chorus of warming concern. These meteorologists were not only Americans. Expert interest in the carbon dioxide threat had arisen during the late 1970s in Western Europe and Russia as well. However, there seemed to be nothing in particular that had triggered this interest. There was no new evidence of particular note. Nor was there any global warming to speak of. Global mean temperatures remained subdued, while in 1978 another severe winter descended over vast regions of North America. The policy environment also remained unsympathetic. Pg.184

At last, during the early 1980s, Nature gave some clear signals that it was coming out on the side of the warmers. In the early 1980s it started to become clear that the four-decade general cooling trend was over. Weather station records in the northern mid-latitudes began again to show an upward trend, which was traceable back to a turnaround during the 1970s. James Hansen was early in announcing this shift, and in doing so he also excited a foreboding of manmade warming. Pg.193

Besides, there was a much grander diluvian story that continued to gain currency: the semi-submerged West Antarctic ice sheet might detach and slide into the sea. This was for some an irresistible image of terrible beauty: displacement on a monumental scale, humanity unintentionally applying the lever of industrial emissions to cast off this inconceivably large body of ice. As if imagining some giant icy Archimedes slowly settling into his overflowing bath, Hansen calculated the consequential displacement to give a sea-level rise of 5 or 6 metres within a century. Pg.195

Moreover, it had the imprimatur of the American Association for the Advancement of Science; the AAAS journal, Science, was esteemed in the USA above all others. Thus we can forgive Sullivan his credulity of this string of claims: that the new discovery of ‘clear evidence’ shows that emissions have ‘already warmed the climate’, that this supports a prediction of warming in the next century of ‘almost unprecedented magnitude’, and that this warming might be sufficient to ‘melt and dislodge the ice cover of West Antarctica’. The cooling scare was barely in the grave, but the warmers had been rehearsing in the wings. Now their most daring member jumped out and stole the show. Pg.196

But Hansen went beyond this graph and beyond the conclusion of his published paper to firstly make a strong claim of causation, and then, secondly, to relate this cause to the heat being experienced that year (indeed, the heat being experienced in the hearing room even as he spoke!). He explained that ‘the Earth is warmer in 1988 than at any time in the history of instrumental measurements’. He had calculated that ‘there is only a 1 percent chance of an accidental warming of this magnitude. . . ’ This could only mean that ‘the greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now’. Hansen’s detection claim was covered by all the main television network news services and it won for him another New York Times front page headline: Global warming has begun, expert tells Senate. Pg.224

The Exaggeration

Where SCOPE 29 looked toward the time required for a doubling of the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, at Villach the policy recommendation would be based on new calculations for the equivalent effect when all emitted greenhouse gases were taken into account. The impact of the new calculations was to greatly accelerate the rate of the predicted warming. According to SCOPE 29, on current rates of emissions, doubling of the carbon dioxide concentration would be expected in 2100. At Villach, the equivalent warming effect of all greenhouse gases was expected as early as 2030. Pg.209

This new doubling date slipped under a psychological threshold: the potential lifetime of the younger scientists in the group. Subsequently, these computations were generally rejected and the agreed date for ‘the equivalent of CO2 doubling’ was pushed out at least 20 years; indeed, never again would there be a doubling estimate so proximate with the time in which it was made. Pg.209

Like so many of the consensus statements from this time on, this one is twisted so that it gives the appearance of saying more than it actually does. In this way, those pushing for dramatic effect and those concerned not to overstate the case can come to agreement. In fact, this passage of the statement brings the case for alarm down to the reliability of the modelling, which is pretty much true of SCOPE 29. Pg.210

In other words, the Impact on Climate Change working group concluded that the models are not yet ready to make predictions (however vaguely) about the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the global climate. Pg.210

The Legacy

Today, emissions targets dominate discussions of the policy response to global warming, and total emissions rates are tacitly assumed to be locked to a climatic response of one, two or so many degrees of warming. Today’s discussions sits on top of a solid foundation of dogma established across several decades and supposedly supported by a scientific consensus, namely that there is a direct cause–effect temperature response to emissions. Pg.219

One of the main recommendations for mitigating these dire consequences is a comprehensive global treaty to protect the atmosphere. On the specific issue of global warming, the conference statement calls for the stabilisation of atmospheric concentrations of one greenhouse gas, namely carbon dioxide. It estimates that this would require a reduction of current global emissions by more than 50%. However, it suggests an initial goal for nations to reduce their current rates of carbon dioxide emission by 20% by 2005. This rather arbitrary objective would become the headline story: ‘Targets agreed to save climate’. And it stuck. In the emissions-reduction policy debate that followed, this ‘Toronto target’ became the benchmark. For many years to come—indeed, until the Kyoto Protocol of 1997—it would be a key objective of sustainable development’s newly launched flagship. Pg.221

Summary

The framework for international action is established presuming that CO2 emissions directly cause global warming and that all nations must collectively cut their use of fossil fuels. However, the drive for a world treaty is hampered by a lack of proof and scientists’ mixed commitment to the policy goals.

The IPCC Scare

The Context

Before winter closed in at the end of 1988, North America was brimming with warming enthusiasm. In the USA, global warming was promised attention no matter who won the presidential election. In Canada, after the overwhelming success of the Toronto conference, the government continued to promote the cause, most enthusiastically through its environment minister Tom McMillan. Elsewhere among world leaders, enthusiasm was also building. The German chancellor, Helmut Kohl, had been a long-time campaigner against fossil fuels. Pg.224

In February 1989, the year got off to a flying start with a conference in Delhi organised by India’s Tata Energy Research Institute and the Woods Hole Research Center, which convened to consider global warming from the perspective of developing countries. The report of the conference produced an early apportionment of blame and a call for reparations. It proclaimed that the global warming problem had been caused by the industrially developed countries and therefore its remediation should be financed by them, including by way of aid to underdeveloped countries. This call was made after presenting the problem in the most alarming terms: Global warming is the greatest crisis ever faced collectively by humankind, unlike other earlier crises, it is global in nature, threatens the very survival of civilisation, and promises to throw up only losers over the entire international socio-economic fabric. The reason for such a potential apocalyptic scenario is simple: climate change of geological proportions are occurring over time-spans as short as a single human lifetime. Pg.226

Throughout 1989, the IPCC working groups conducted a busy schedule of meetings and workshops at venues around the northern hemisphere. Meanwhile, the outpouring of political excitement that had been channelled into the process brought world attention to the IPCC. By the time of its second full session in June 1989, its treaty development mandate had become clearer: the final version of the resolution that had passed at the UN General Assembly the previous December—now called ‘Protection of global climate for present and future generations of mankind’—requested that the IPCC make recommendations on strengthening relevant existing international legal instruments and on ‘elements for inclusion in a possible future international convention on climate.’ pg.242

The Alarm

The general feeling in the research community that the policy process had surged ahead of the science often had a different effect on those scientists engaged with the global warming issue through its expanded funding. For them, the situation was more as President Bush had intimated when promising more funding: the fact that ‘politics and opinion have outpaced the science’ brought the scientists under pressure ‘to bridge the gap’pg.253

This is what became known as the ‘first detection’ program. With funding from DoE and elsewhere, the race was soon on to find ways to achieve early detection of the climate catastrophe signal. More than 10 years later, this search was still ongoing as the framework convention to mitigate the catastrophe was being put in place. It was not so much that the ‘conventional wisdom’ was proved wrong; in other words, that policy action did not in fact require empirical confirmation of the emissions effect. It was more that the policy action was operating on the presumption that this confirmation had already been achieved. Pg.254

The IPCC has warned that if CO2 emissions are not cut by 60 percent immediately, the changes in the next 60 years may be so rapid that nature will be unable to adapt and man incapable of controlling them. The policy action to meet this threat—the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change—went on to play a leading role as the headline outcome of the entire show. The convention drafted through the INC negotiation over the previous two years would not be legally binding, but it would provide for updates, called ‘protocols’, specifying mandatory emissions limits. Towards the end of the Earth Summit, 154 delegations put their names to the text. Pg.266

The Exaggeration

It may surprise readers that even within the ‘carbon dioxide community’ it was not hard to find the view that the modelling of the carbon dioxide warming was failing validation against historical data and, further upon this admission, the suggestion that their predicted warming effect is wrong. In fact, there was much scepticism of the modelling freely expressed in and around the Carbon Dioxide Program in these days before the climate treaty process began. Those who persisted with the search for validation got stuck on the problem of better identifying background natural variability. There did at least seem to be agreement that any recent warming was well within the bounds of natural variability. Pg.261

During the IPCC review process, Wigley was asked to answer the question that he had avoided in the SCOPE 29: When is detection likely to be achieved? He responded with an addition to the IPCC chapter that explains that we would have to wait until the half-degree of warming that had occurred already during the 20th century is repeated. Only then are we likely to determine just how much of it is human-induced. If the carbon dioxide driven warming is at the high end of the predictions, then this would be early in the 21th century, but if the warming was slow then we may not know until 2050 (see Figure 15.1). In other words, scientific confirmation that carbon dioxide emissions is causing global warming is not likely for decades. Pg.263

These findings of the IPCC Working Group 1 assessment presented a political problem. This was not so much that the working group was giving the wrong answers; it was that it had got stuck on the wrong questions, questions obsolete to the treaty process. The IPCC first assessment was supposed to confirm the scientific rationale for responding to the threat of climate change, the rationale previously provided by the consensus statement coming out of the 1985 Villach conference. After that, it would provide the science to support the process of implementing a coordinated response. But instead of confirming the Villach findings, it presented a gaping hole in the scientific rationale. Pg.263

Scientist-advocates would continue their activism, but political leaders who pledged their support for climate action had invested all scientific authority for this action in the IPCC assessment. What did the IPCC offer in return? It had dished up dubiously validated model projections and the prospect of empirical confirmation perhaps not for decades to come. Far from legitimising a treaty, the scientific assessment of Working Group 1 provided governments with every reason to hesitate before committing to urgent and drastic action. Pg.263

In 1995, the IPCC was stuck between its science and its politics. The only way it could save itself from the real danger of political oblivion would be if its scientific diagnosis could shift in a positive direction and bring it into alignment with policy action. Without a positive shift in the science, it is hard to see how even the most masterful spin on another assessment could serve to support momentum towards real commitment in a binding protocol. With ozone protection, the Antarctic hole had done the trick and brought on agreement in the Montreal Protocol. But there was nothing like that in sight for the climate scare. Without a shift in the science, the IPCC would only cause further embarrassment and so precipitate its further marginalisation. Pg.278

For the second assessment, the final meeting of the 70-odd Working Group 1 lead authors was scheduled for July 1995 in Asheville, North Carolina. This meeting was set to finalise the drafting of the chapters in response to review comments. It was also (and mostly) to finalise the draft Summary for Policymakers, ready for intergovernmental review. The draft Houghton had prepared for the meeting was not so sceptical on the detection science as the main text of the detection chapter drafted by Santer; indeed it contained a weak detection claim. However, it matched the introduction to the detection chapter, where Santer had included the claim that ‘the best evidence to date suggests’. . . .. . a pattern of climate response to human activities is identifiable in observed climate records.

This detection claim appeared incongruous with the scepticism throughout the main text of the chapter and was in direct contradiction with its Concluding Summary. It represented a change of view that Santer had only arrived at recently due to a breakthrough in his own ‘fingerprinting’ investigations. These findings were so new that they were not yet published or otherwise available, and, indeed, Santer’s first opportunity to present them for broader scientific scrutiny was when Houghton asked him to give a special presentation to the Asheville meeting. Pg.279

However, the results were also challenged at Asheville: Santer’s fingerprint finding and the new detection claim were vigorously opposed by several experts in the field. One of the critics, John Christy, recalls challenging Santer on his data selection. Santer recalls disputing the quality of the datasets used by Christy. Debates over the scientific basis of the detection claim dominated the meeting, sometimes continuing long after the formal discussions had finished and on into the evening. Pg.280

In September, a draft summary of the entire IPCC second assessment was leaked by the New York Times, the new detection claim revealed on its front page. Pg.281

The UK Independent headlined ‘Global Warming is here, experts agree’ with

the subheading: ‘Climate of fear: Old caution dropped as UN panel of scientists concur on danger posed by greenhouse gases.‘ The article explains the breakthough: “The panel’s declaration, after three days of torturous negotiation in Madrid, marks a decisive shift in the global-warming debate. Sceptics have claimed there is no sound evidence that climate has been changed by the billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping ‘greenhouse gases’ spewed into the atmosphere each year, mostly from the burning of fossil fuels and forests. But the great majority of governments and climate scientists now think otherwise and are now prepared to say so. ‘The balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate’, the IPCC’s summary of its 200-page report says. The last such in-depth IPCC report was published five years ago and was far more cautious.” Pg.283

The Legacy

Stories appearing in the major newspapers over the next few days followed a standard pattern. They told how the new findings had resolved the scientific uncertainty and that the politically motivated scepticism that this uncertainty had supported was now untenable. Not only was the recent success of the attribution finding new to this story; also new was the previous failure. Before this announcement of the detection breakthrough, attention had rarely been drawn to the lack of empirical confirmation of the model predictions, but now this earlier failure was used to give a stark backdrop to the recent success, maximising its impact and giving a scientific green light to policy action. Thus, the standard narrative became: success after the previous failure points the way to policy action. Pg.284

With so many political actors using the authority of the IPCC’s detection finding to justify advancing in that direction, it is hard to disagree with his assessment. Another authority might well have been used to carry the treaty politics forward, but the fact that this particular authority was available, and was used, meant that the IPCC was hauled back into the political picture, where it remains the principal authority on the science to this day. Pg.301

What we can see from all this activity by scientists in the close vicinity of the second and third IPCC assessments is the existence of a significant body of opinion that is difficult to square with the IPCC’s message that the detection of the catastrophe signal provides the scientific basis for policy action. Most of these scientists chose not to engage the IPCC in public controversy and so their views did not impact on the public image of the panel. But even where the scientific basis of the detection claims drew repeated and pointed criticism from those prepared to engage in the public controversy, these objections had very little impact on the IPCC’s public image. Pg.310

Today, after five full assessments and with another on the way, the IPCC remains the pre-eminent authority on the science behind every effort to head off a global climate catastrophe. Pg.310

Summary:

Today the IPCC is a testament to the triumph of politics over science, of style and rhetoric over substance and evidence. A “bait and switch” gambit was applied at the right moment to produce the message wanted by the committed. Fooled by the finesse, the media then trumpeted the “idea whose time has come,” and the rest is history, as they say. And yet, despite IPCC claims to the contrary, the detection question is still not answered for those who demand evidence.

Thank you Bernie Lewin and GWPF for setting the record straight, and for demonstrating how this campaign is sustained by unfounded fears.

A continuing supply of hot air keeps scare balloons inflated.

This article

This article

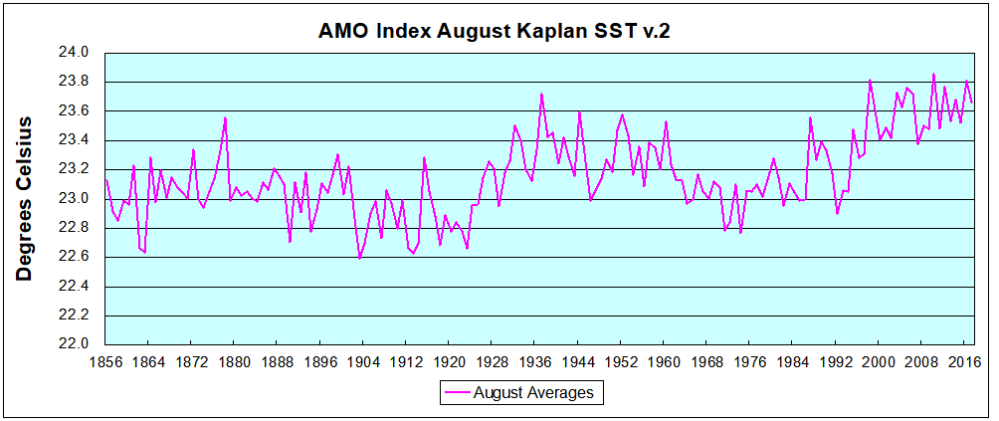

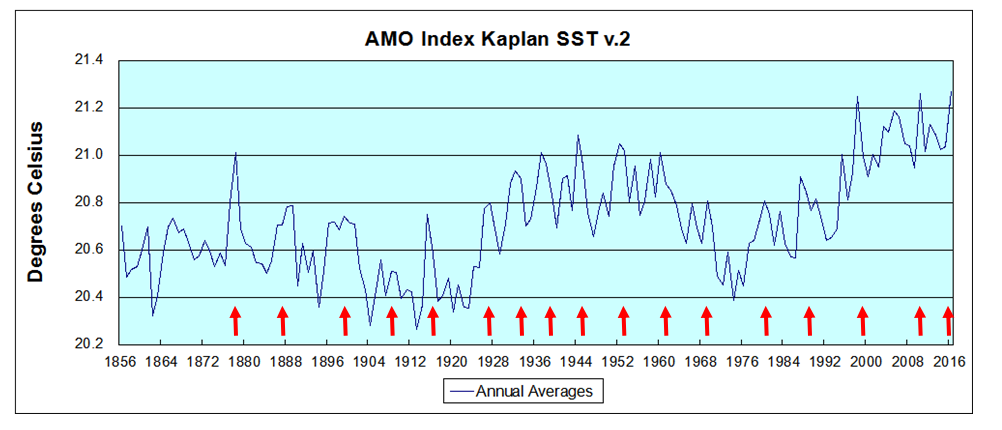

The data is annual averages of absolute SSTs measured in the North Atlantic. The significance of the pulses for weather forecasting is discussed in

The data is annual averages of absolute SSTs measured in the North Atlantic. The significance of the pulses for weather forecasting is discussed in