This is not a religious book in the sense of its being meant to convey a religious message or for people of a particular religion—it is a book containing three journalistic reports about a religion, or a sort of religion, that emerged from and then subsumed the environmental movement. Today, that movement is a kind of cult and not a political movement at all, if it ever was one. Those who profess one of the Abrahamic faiths have a religious interest in idolatry because it perverts religion and leads religion to inhuman ends—Norman Podhoretz, in his very interesting book The Prophets, describes the ancient Israelite “war on idolatry” as a matter that is not exclusively otherworldly but very much rooted in a campaign against the ghastly social practices associated with idolatry: cannibalism, child sacrifice, etc.

And if idolatry makes a hash of religion, it is, if anything, even more of a menace

to the practice of politics, which is my subject.

I suspect that some of you may object to the term idolatry here, or to the description of the environmental movement as a kind of cult—that some readers may regard these as rhetorical excesses. All that I have to say in my defense is that this is a factual and literal account of what I have seen and heard in reporting about the environmental movement, in the actual explicit religious ceremonies that were conducted in and around the United Nations climate conference in Glasgow in 2021, in my conversations with such figures as the “voluntary human extinction” activist who calls himself Les U. Knight, in my conversations with those who object to clean and economical nuclear power on grounds that are, even when not accompanied by pseudo- religious Gaia rhetoric, fundamentally metaphysical. What is at work is a kind of sophomoric, cartoon puritanism that regards modernity—and, in particular, the extent and pattern of consumption in the modern developed world— as sinful. One need not squint too much to recognize very old Christian (or even Stoic) aversion to “luxury” in these denunciations.

Indeed, we need only take the true believers at their word. As scientists have been searching for economic, abundant, and environmentally responsible sources of energy to support human flourishing, the environmentalists have resisted and abominated these efforts: Amory Lovins of Friends of the Earth declared that “it would be little short of disastrous for us to discover a source of clean, cheap, abundant energy”—and please note there the inclusion of clean—while Population Bomb author Paul Ehrlich famously opined that “giving society cheap, abundant energy at this point would be the equivalent of giving an idiot child a machine gun.” Professor Ehrlich gives up the game with “at this point”—meaning, of course, in our fallen, postlapsarian state.

It was, of course, inevitable that Professor Ehrlich— who has been spectacularly wrong about practically every prediction he has made in his lucrative career as a secular, Malthusian prophet—should be back in the news at the same time scientists were announcing a breakthrough in nuclear fusion research. Professor Ehrlich, recently seen on 60 Minutes (which still exists!) and elsewhere, downplays the recent advance in fusion on the grounds that current patterns of human living are “unsustainable.” Professor Ehrlich has been giving the same interview for decade and decades—advances in energy production will not matter because “the world will have long since succumbed to overpopulation, famine,” and other ills, as he insisted in an interview published by the Los Angeles Times—in 1989— not long after insisting that the United Kingdom would be ravished by famine no later than the year 2000.

End-of- days stories have long been a staple of religions and cults of many different kinds and characters, of course, and the environmental movement is fundamentally eschatological in its orientation, by turns utopian and apocalyptic. It is at the moment more apocalyptic than utopian, but that is a reflection of a broader trend in our politics and our society. The Western world, in particular, the English-speaking Western world, has been fervently praying for its own demise for a generation. Future historians will note the prevalence of zombie-apocalypse stories in our time—The Walking Dead has recently concluded its main series but will be supplemented by numerous spinoffs, while one of the most intensely anticipated television series of 2023 is The Last of Us, an adaptation of a video game that is based on yet another variation of the zombie-apocalypse theme—but beyond zombie-apocalypse stories we have alien-invasion- apocalypse stories, and, precisely to our point here, eco-apocalypse stories by the dozen (The Day After Tomorrow, Snowpiercer, Waterworld, Interstellar, Wall-E).

What these stories have in common is not the particular source of anxiety, though environmental concerns are interlaced into many stories: The Last of Us is a zombie story, but the zombies are produced by global warming, which allows a particular fungus to colonize and control human brains. (One shared article of faith that is present not only in zombie movies but also from campy, anencephalic or macrocephalic aliens of Mars Attacks! and Independence Day—the enemy is the brain.) What they have in common, rather, is a two-sided fascination with social collapse, both the negative aspects—the inevitable suffering—and the positive—the possibility of a return to innocence and a shared born-against experience that retroactively sanctifies that suffering.

Which is to say, what we have here is the old mythological cycle

of suffering, death,and rebirth told at the social level

rather than at the level of individual hero or martyr.

None of this is to say that there are not real environmental challenges in front of us. These are real, and they deserve serious attention. But here in the third decade of the benighted 21st century, the environmental movement is not about that. It is an apocalyptic-fantasy cult. Of course there are people who think of themselves as adherents of that movement who are doing real work in science and policy, in much the same way that the alchemists and magicians of the medieval period laid the foundations for much of modern science, including a great deal of chemistry and astronomy. The two phenomena are by no means mutually exclusive.

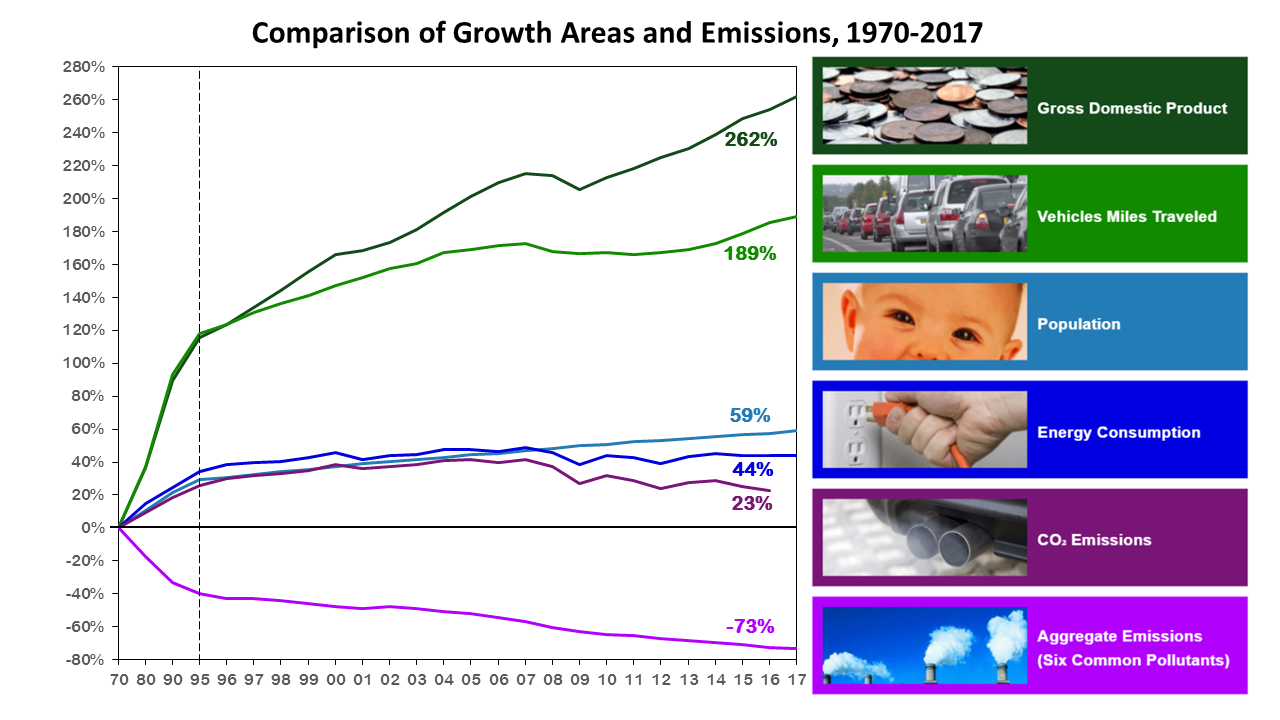

But if you want to understand why there has been so frustratingly little meaningful progress in environmental policy in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union in the past 30 years or so, then understanding the cultic character of the environmental movement is essential. The real environmental-policy debate should be, not to put too fine a point on it, boring, though by no means simple—a largely technical matter of understanding tradeoffs and drawing up policies that attempt to balance competing goods (environmental, recreational, economic, social, etc.) and putting those policies to the test of democratic accountability. None of this is easy in a connected and global world—prohibit the use of coal in the United States and you might end up increasing worldwide coal-related greenhouse-gas emissions as relatively dirty power plants in China and India take up the slack in consumption—but none of it ought to present a Manichean conflict, either.

Demagoguery is an old and obvious factor in all political discourse, but there is at work here something deeper than mere political opportunism, and that is the invariable human need, sometimes subtly realized, to rewrite complex stories as simple stories, replacing real-world complexity with the anaesthetizing simplicity of heroes and villains. We have been here before, of course. Consider Robert Wiebe’s anthropology of bureaucracy in the Progressive Era in The Search for Order:

The sanguine followers of the bureaucratic way constructed their world on a comfortable set of assumptions. While they shaded many of the old moral absolutes, they still thought in terms of normal and abnormal. Rationality and peace, decent living conditions and equal opportunity, they considered “natural”; passion and violence, slums and deprivation, were “unnatural.” Knowledge, they were convinced, was power, specifically the power to guide men into the future. Consequently, these hopeful people also exposed themselves to the shock of bloody catastrophe. In contrast to the predetermined stages of the idealists, however, bureaucratic thought had made indeterminate process central to its approach. Presupposing the unexpected, its adherents were most resilient just where the idealists were most brittle.

Of course, the assumptions described by Wiebe are precisely backward:

It is deprivation and violence that are natural, peace and plenty that are unnatural.

As Thomas Sowell famously observed, poverty has no causes— prosperity has causes, while poverty is the natural state of human affairs, present and effective ex nihilo. But the conflation of the natural and the desirable is always with us: Like most Americans, I treasure our national parks and have spent many enjoyable days in them, but it is difficult to think of any environment anywhere on Earth that is less natural than Yellowstone, the highly artificial environment that is the product of planning and policy, for instance in the programmatic introduction of grey wolves and other species.

To subscribe to a genuinely natural view of the world and man’s place in it, as opposed to a quasi-religious environmental dualism, is to understand man as integral part of nature, in which case you might think of Midtown Manhattan as a less artificial and more organic environment than Yellowstone, its features and patterns considerably more spontaneous than what one finds in a diligently managed nature preserve. If, on the other hand, you understand the natural world and the wild places in it principally as a paradisiac spiritual counterpoint to the fallen state of man as represented in our urban and technological civilization, then you cannot make any kind of reasonable tradeoff calculation when it comes to, say, drilling for gas in the Arctic, which must be regarded not as a poor policy choice but as a profanation, a “violation” of that which is “pristine” and “sacred”—words that one commonly hears applied to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and to many less exalted swamps and swathes of tundra.

For myself, what I want is a boring environmental policy, one that is, in Wiebe’s terms, less brittle and more resilient, one that in “presupposing the unexpected” is able to account for developments that complicate our environmental policies by enmeshing them in other policies that they also complicate. For example, try putting yourself in the position of a responsible policy analyst in 1968, when Ehrlich’s Population Bomb hit the shelves. In 1968, it would have been very difficult to imagine the subsequent transformation of China into a modern economic power—and even more difficult to imagine that this development would be not entirely and unqualifiedly good for the world, given the resources it has put at the disposal of what today must be regarded as history’s most encompassing and sophisticated police state. (So far.)

But instead of a political discourse that can take such developments on their own terms

and put them into a context of competing goods and tradeoffs,

we end up instead with a parade of Great Satans.

For the environmental cultists, the Great Satan is Exxon; for certain self-described nationalists in the United States, the Great Satan is the Chinese Communist Party; the strangely durable Marxists and the neo-nationalists on the Right have, with utter predictability, converged on their choice of Great Satans, these being transnational “elites.” And so the religious appetite is satisfied through politics, including, in a particularly intense way, through environmental politics. To take one example that seems very obvious to me, the United States and much of the rest of the world, including the developing world, would be much better off on practically every applicable metric if there were wider and more sophisticated deployment of nuclear power, which is not a panacea by any means, but is a reliable, economical, and effectively zero-emissions way to produce electricity at utility scale. The case against nuclear power might be described, in generous terms, as “moral” or “pseudo-religious” but might be described more accurately as “superstitious.” But maybe that kind of metaphysical primitivism is to be expected from a political movement whose economic agenda includes a great deal of physical primitivism as well: In the neo-Neolithic future of their dreams, there won’t be much to do in the evenings except bark at the moon, so one may as well try to imbue it with some transcendent meaning.

The environment matters. So do property rights, trade, development, agriculture, medicine, energy, the rule of law, democracy, and the uncountable other constituent elements of human flourishing. A reasonable environmental policy can work with that, but a spiritualized and cultic environmental policy cannot. I hope these reports will help to make it clear just how real the choice between these two kinds of environmentalism is.

Kevin D. Williamson