Ruy Teixeira writes at his substack blog From Environmentalism to Climate Catastrophism: A Democratic Story (Part 1 of 3). Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

Ruy Teixeira writes at his substack blog From Environmentalism to Climate Catastrophism: A Democratic Story (Part 1 of 3). Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

Conservation, the Environmental Apocalypse, and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism

The beginnings of the environment as an issue can be traced to the conservation movement of the late 19th and early 20th century associated with figures like Gifford Pinchot, head of the Forest Service under Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club. They were Republicans but many Democrats also embraced the movement; Woodrow Wilson created the National Park Service in 1916. And the New Deal in the 1930’s had a prominent place for conservation activities, most famously in the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) where young men were employed to improve forests and national parks. Trail systems and lodges from that era are still widely used today.

With varying degrees of strictness the conservation movement’s guiding principle was to insulate unspoiled parts of nature from development by market forces, thereby preserving them for healthy leisure and recreation. The movement, like all future iterations of the environmental movement, assumed an unending conflict between man and nature that required good people to take the side of nature.

As development proceeded over the course of the 20th century, the stresses on nature became ever larger and more obvious, leading to the emergence after World War II of an apocalyptic strain in the conservation movement. The argument gained traction that economic and population growth would, if unchecked, destroy the environment and lead to civilizational collapse. Accompanying that strain was a milder version of the idea that directly challenged the old conservation ethos: simply conserving what was left of nature was not enough. The reality of the interdependent natural world meant that man’s activities were having dire effects everywhere on the planet—where people lived and where they didn’t. These activities were upsetting a finely balanced system, resulting in the degradation of both nature, as conventionally understood, and people’s lives.

Restoring and preserving that balance was what it meant to be an environmentalist.

The movement proved enormously effective as a reform movement. Carson’s book veered toward the apocalyptic, but the movement she inspired was laser-focused on practical reforms that would immediately reduce pollution and safeguard the environment. A raft of legislation in the Johnson administration followed like the Clean Air and Water Quality Acts and, in the Nixon administration, the creation of the Environmental Protection Act and the promulgation of the NEPA (National Environmental Protection Act) standards. This legislation and subsequent action was directly responsible for a radical reduction in pollution of all kinds in the next decades.

But the apocalyptic strain of environmentalism, which saw industrial society as an imminent threat to human life and to the planet, was not eliminated by these reforming successes. Instead a closer relationship evolved between mainstream environmentalism and a radical view of the fundamental dangers of industrial society. The first manifestation of this was the anti-nuclear power movement which arose in the 1970’s and was turbo-charged by the 1979 Three Mile Island incident, Building on public fears of nuclear meltdowns and radiation poisoning, the movement was successful in stopping the build-out of nuclear power in the United States.

In the 1990’s, as a scientific consensus emerged that greenhouse gases were steadily warming the earth, this movement was superseded by the climate movement. Here was clear proof that industrial society and human civilization were counterposed. Initially meliorist in orientation, the movement has become more radical as it has gathered strength.

The quest to eliminate the possibility of dire scenarios has met the reality

that industrial societies built on fossil fuels are likely to change only slowly,

for both political and technical reasons.

This has promoted a sense that radical action to transform industrial society must be taken as fast as possible. That view has gained hegemony within the Democratic party infrastructure, supporting activist groups and associated cultural elites. Practical objections about the speed with which a “clean energy transition” can be pursued and concerns about effects on jobs and prices are now outweighed for most Democrats by the perceived urgency of the mission. That has set the Democrats apart from the working class voters they aspire to represent for whom these practical objections and concerns loom large.

It has become a significant factor in the Great Divide that has opened between postindustrial metros and the rural areas, towns and small cities of middle America.

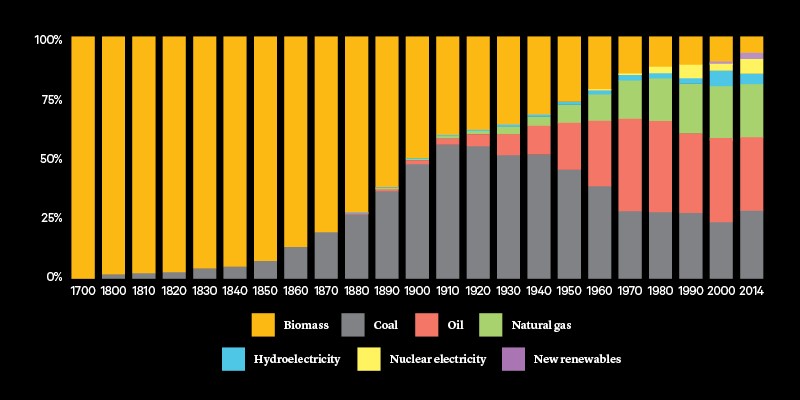

See World of Energy Infographics

After World War II the movement took a different turn. The devastation of the war, combined with the breakneck pace of economic development, fed a sense that industrial civilization was out of control and threatened the entire planet. The key figures promulgating this view were Henry Fairfield Osborn Jr. (Our Plundered Planet, 1948) and especially William Vogt, whose Road to Survival was also published in 1948. Vogt was an ornithologist and ecologist whose experiences in the developing world had convinced him that economic growth and overpopulation would inevitably lead to civilizational collapse unless both growth and population were radically curtailed.

Vogt argued that beliefs in progress were weighing humanity down and were actually “idiotic in an overpeopled, atomic age, with much of the world a shambles.” He concluded that the road to survival could only lie in maximizing use of renewable resources and accepting lower living standards or reduced population.

In his language and outlook, one can see all the strands of apocalyptic environmentalism (now focused on climate change) that we see today. This especially applies to his description of the United States and its economic system.

More benignly, Vogt’s (and Osborn’s) books marked the evolution of conservationism into environmentalism. Stripped of the apocalyptic verbiage, they were arguing that conservation of nature was not enough. The interdependence of man and nature meant that human activities could not be isolated and instead were having negative effects on the entire planet—wilderness, settled areas, oceans, everywhere. The balance of nature was being destroyed, dragging down the natural world and humanity with it. Restoring that balance, not merely conserving parts of the ecosystem, was the new meaning of being an environmentalist.

Also key to Vogt’s analysis was the concept of “carrying capacity”—how much the environment/planet could sustainably bear of a species’ imprint before disaster ensued. This was not precisely defined but it is easy to see the relationship of this idea to how climate change is conventionally thought of today.

The burgeoning strength of the environmental movement started what became a blizzard of legislative action to protect the environment and roll back pollution. That began under LBJ with the Clean Air Act, Solid Waste Disposal Act, Water Quality Act and Air Quality Act. Then under Nixon there was the National Environmental Policy Act, proximate to the Santa Barbara oil spill and widely-publicized Cayahoga River fire, establishing the (NEPA) environmental standards and reviews that are still with us today. Also under Nixon, the Environmental Protection Agency was established, the Clean Water and Endangered Species Acts passed and the Clean Air act strengthened. The first Earth Day was on April 22, 1970, clearly marking the environmental issue as a mass cause for those on the left of the political spectrum.

An interesting aspect of all this activity is that it was meliorist and profoundly reformist. That is, despite its origins in the Vogtian Silent Spring, with its apocalyptic overtones, the drive to clean up the environment was pursued through a steady accumulation of legislation and consciousness-raising about the issue. There was a sense that the problem was solvable through such activities and did not require the massive changes in economic activity and human behavior that an advocate like Vogt would have called for. Of course, there was always a radical fringe of the environmental movement, typified by Edward Abbey’s 1975 novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang, and the Earth First! group, formed in 1980, but they were a small and not particularly influential part of the overall movement.

Not only was environmentalism of this era reformist but it was very successful reformism. Consider: Because we are now so used to having a fairly clean environment in terms of air and water quality, it is easy to forget just how far we have come since the early 1960’s. Rivers and lakes back then were far more likely to be polluted and essentially unsafe for human activity than not; the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland famously caught fire in 1969. But since that era, water quality has improved dramatically; the number of water bodies meeting standard quality criteria has roughly doubled. Such icons of pollution as Boston Harbor have been cleaned up. And everywhere towns and cities are investing in waterfront leisure developments that would have been a tasteless joke a generation ago.

Air quality has increased dramatically as well. Between 1970 and 2021, emissions of the six key air pollutants that impact public health—ozone, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and lead—were cut by 78 percent, even as GNP has increased increased by nearly 400 percent. Acid rain has declined by two-thirds and smog is down by about a third. These trends are truly amazing and would have been considered scarcely believable back in 1970. They underscore the tremendous success of modern reformist environmentalism.

See also Progressively Scaring the World (Lewin book synopsis)

Reblogged this on Calculus of Decay .

LikeLike