Leszek Marks explains how warming and cooling alternated throughout the last 12,000 years and how our modern period is no different in his paper Contemporary global warming versus climate change in the Holocene. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images. H/T No Tricks Zone

Abstract

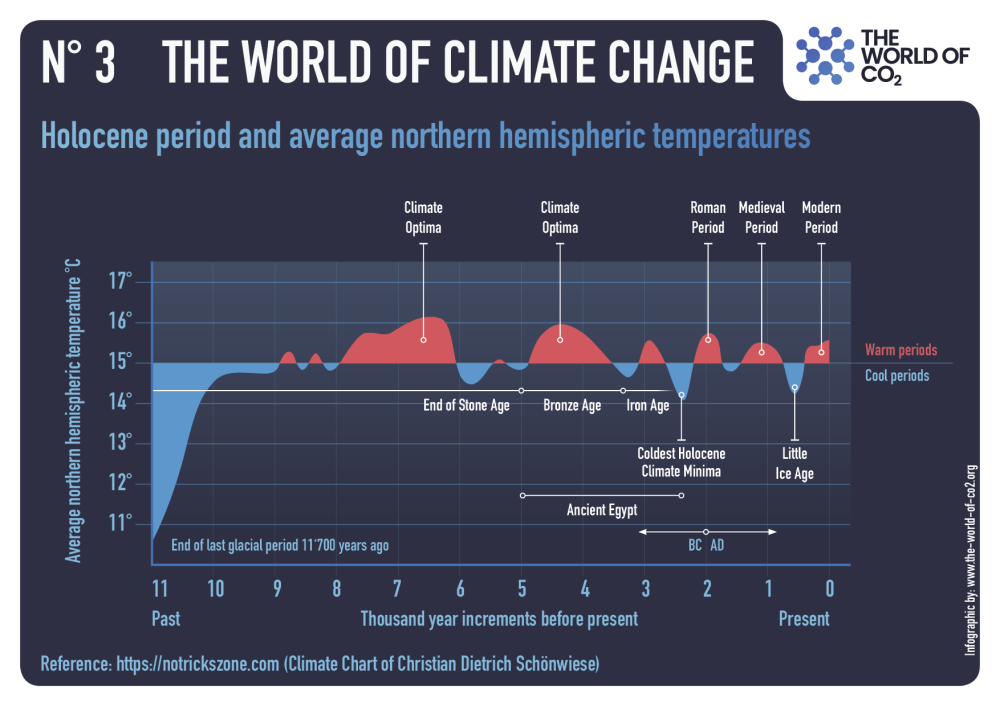

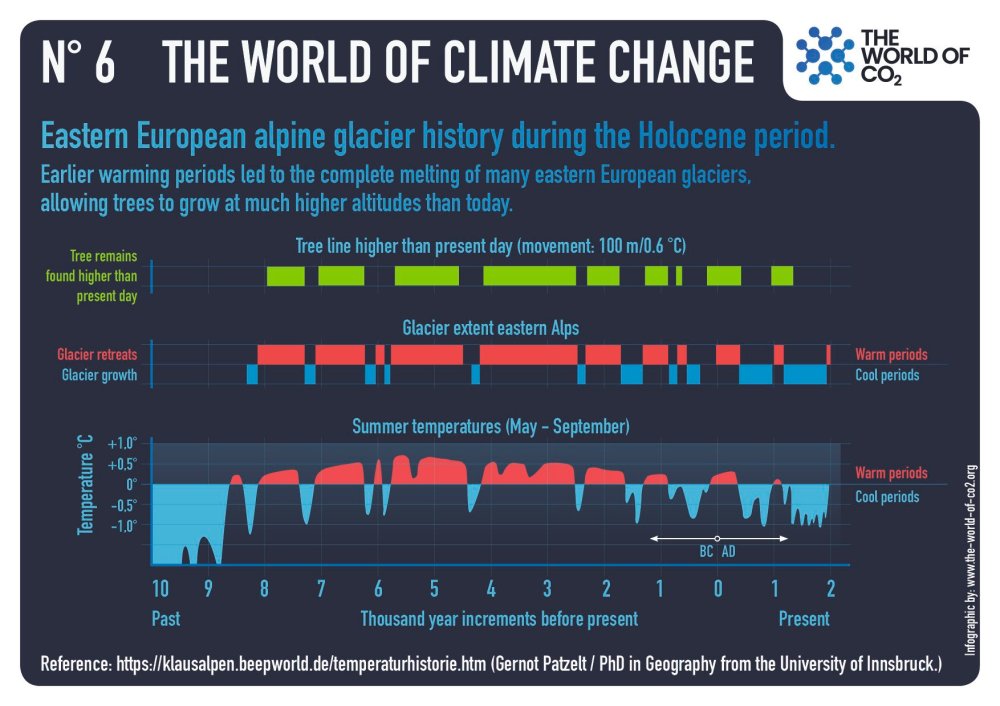

Cyclical climate change is characteristic of the Holocene, with successive warmings and coolings. A solar forcing mechanism has steered Holocene climate change, expressed by 9 cooling phases known as Bond events. There is reliable geological evidence that the temperatures of most warming phases in the Holocene were globally higher or similar to that of the current warming period, Arctic sea ice was less extensive and most mountain glaciers in the northern hemisphere either disappeared or were smaller.

During the African Humid Period in the Early and Middle Holocene, much stronger summer monsoons made the Sahara green with growth of savanna vegetation, huge lakes and extensive peat bogs. The modern warming is part of a climatic cycle with a progressive warming after the Little Ice Age, the last cold episode of which occurred at the beginning of the 19th century. Successive climate projections of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are based on the assumption that the modern temperature rise is steered exclusively by the increasing content of human-induced CO2 in the atmosphere. If compared with the observational data, these projected temperatures have been highly overestimated.

Overview

This paper presents the current state of knowledge of the climate change in the Holocene. The geological record of the climate change in this epoch has been verified by the results of archaeological, historical and meteorological investigations (Marks, 2016). Determination of the steering forces of modern warming is among the current scientific priorities in the world and, therefore, geological input is an important contribution to the discussion about human impact on the climate.

The current interglacial of the Holocene started 11.7 ka cal BP (Walker et al., 2018), with progressively increasing human impact on the Earth’s environment, especially strong during the past decades (Gibbard et al., 2021). Geological examination of past climate changes is crucial to distinguish the natural and the human-induced factors of the current climate change. The most important climate-steering factor is solar radiation, subjected to cyclical changes caused by the Sun’s activity that supplies with over 99% of the energy that is responsible for the climate of the Earth. Geological reconstructions show that rises and falls in the temperature on the Earth are dependent on the sunspot cycles (Table 1; Easterbrook, 2011; Usoskin et al., 2016; Usoskin,2023), and these in turn respond to the varying magnetic activity of the Sun.

The natural input of solar energy is transformed by different external and internal factors to modulate climate on the Earth. Latitudinal insolation in the Holocene depended on the Earth’s orbital parameters (Milankovič cycles). In comparison with the present values, summer temperatures in the northern hemisphere were higher in the Early and Middle Holocene (Beer, Van Geel, 2008; Beer, Wanner, 2012). Winter temperatures in the southern hemisphere were higher in the Middle Holocene, followed by higher temperatures in the northern hemisphere in the Late Holocene. In the coming 3 ka, lower temperatures are expected everywhere, except for the intertropical zone where higher winter temperatures are expected (Marks, 2016).

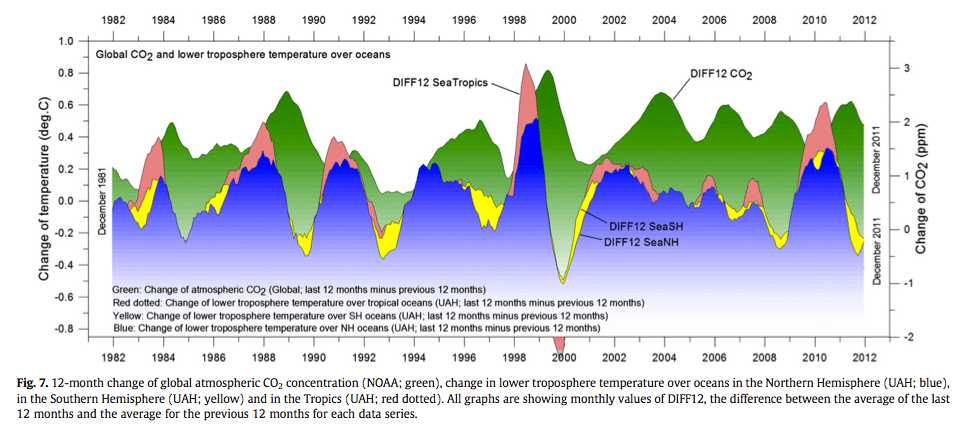

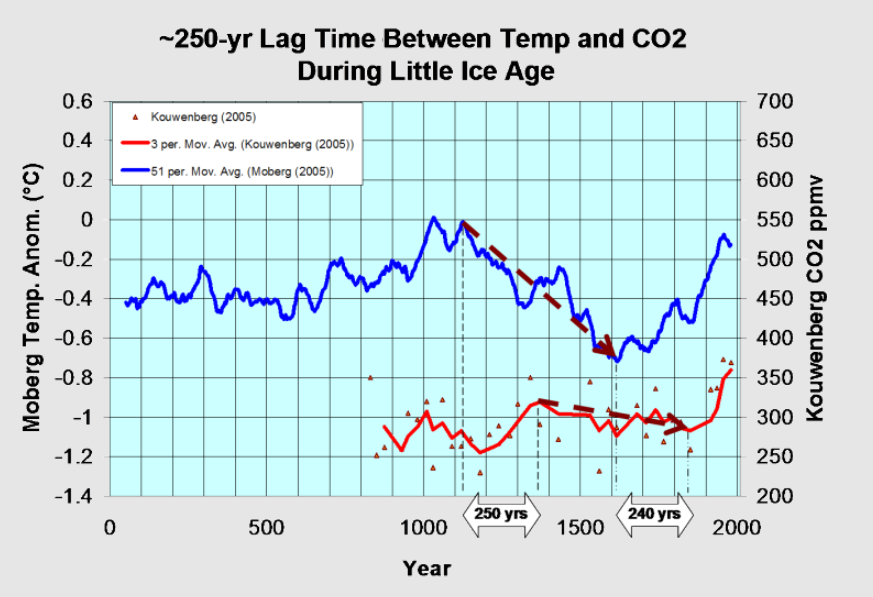

The natural rhythm of climate change during the Holocene was disturbed by large volcanic eruptions. Emission of dust into the atmosphere was responsible for a couple of cold events during the Holocene (Shindell et al., 2003). Such eruptions can be detected by concentrations of SO2 in polar ice core records (Zielinski et al., 1994; Castellano et al., 2004). The extent of the vegetation cover had an important, but very complex, effect on the climate (Foley et al., 2003), because the evaporative cooling by a forest mitigated warmings and limited dust mobilisation (Bonan, 2008). The atmospheric CO2 concentration decreased in the Early Holocene and started to increase since 7 ka, being independent of temperature variations (Palacios et al., 2024a). Ocean-atmosphere interchange was the main source of CO2 until the recent decades when the anthropogenic emission of CO2 became significant (Brovkin et al., 2019).

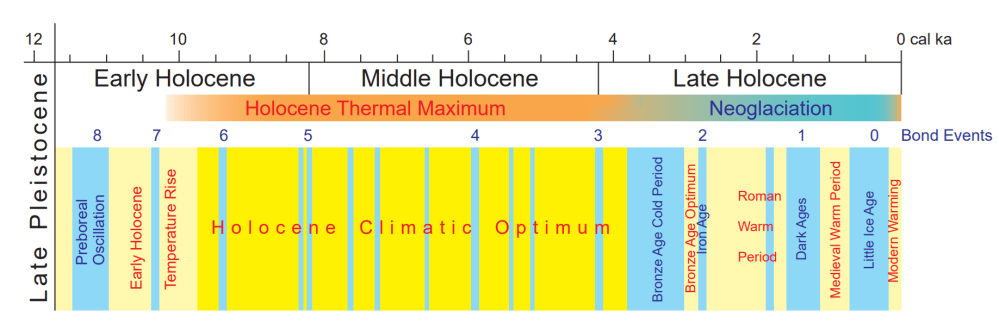

Fig. 1. Climate change in the Holocene, adapted from Palacios et al. (2024a) and modified: warm periods are in yellow and less warm in pale yellow, and cold in blue; Bond Events are after Bond et al. (1997, 2001) and geochronology after Walker et al. (2019).

Climate change after the Holocene Thermal Maximum

The temperature deduced from the oxygen isotope curve in the Greenland ice core GISP2 shows that several warmings occurred after the Holocene Thermal Maximum (Fig. 1; Drake, 2012). These were periods during which great progress in the development of human societies occurred: Late Bronze Age, Roman Warm Period and the MWP. The separating cold Bond Events, named the Iron Age and Dark Ages Cold Periods respectively, were expressed by economic, intellectual and cultural decline. The temperature history since 900 CE was based firstly on the estimated climate history of central England (Lamb, 1977; IPCC, 1990). This showed a distinct warming of ~1.3°C when compared with the LIA (Moberg et al., 2005; D’Arrigo et al., 2006; Mann et al., 2009). This warming was a result of natural processes, because human activity could not have had any significant effect on temperature changes before 1900 CE. The Roman Warm Period (250 BC–450 CE), the MWP (950–1250 CE) and the Modern Warming Period reflect 1000-cycles with high solar radiation (Table 1; Vahrenholt, Lüning, 2014).

Discussion

The claim of the IPCC (2021) that ‘…the latest decade was warmer than any multi-century period after the Last Interglacial, around 125,000 years ago’ ignores all the knowledge about reconstructed temperatures in the Holocene, based on multi-proxy palaeoclimatic data.

Despite the extensive northern ice sheets, the increased summer insolation in the northern hemisphere caused a warming trend from the beginning of the Holocene and lasting until the Middle Holocene (Palacios et al., 2024a). This warming trend was reversed from 6–5 ka onwards, due to decreased summer insolation in the northern hemisphere. Such general warming or cooling trends in the Holocene were interrupted by short periods with opposite and abrupt temperature changes (Fig. 1).

The modern warming represents a part of the cyclical climate change after the LIA, the last cold episode of which occurred at the beginning of the 19th century. The LIA with low temperatures is named the pre industrial period by the advocates of global anthropogenic warming and such an approach helps them to promote the idea that an increased human emission of CO2 (especially in the 20th century) is the only reason for rising temperatures on Earth. They do not bother with the evidence that the mutual time relations of global temperature and contents of CO2 in the atmosphere in 1980–2019 indicate a leading role of temperature, a rise of which was followed in that time by a 6-month delay in the rise of CO2 (Humlum et al., 2012; Koutsoyiannis, Kundzewicz, 2020).

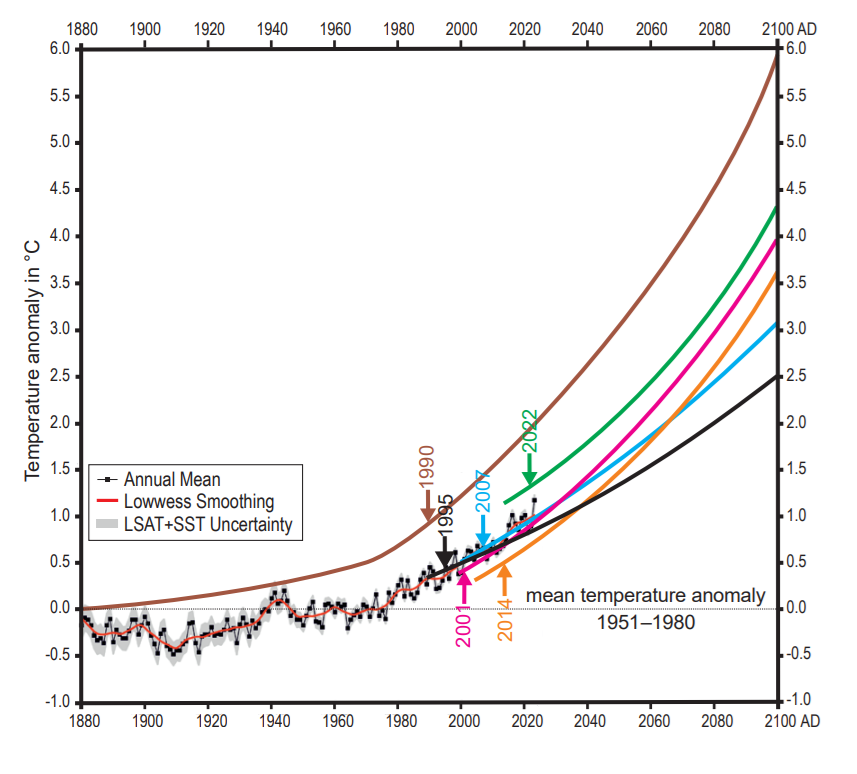

The official curve of the global mean annual temperature anomalies based on regular measurements (https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/graphs_v4/) overlaps slightly with the temperature projections in reports of the IPCC (1990, 1995, 2001, 2007, 2014, 2021). These IPCC projections were created by climate models, based on the assumption that the modern temperature rise is steered exclusively by the increasing content of human-induced CO2 in the atmosphere while the role of water vapour as the main greenhouse gas is neglected (cf. Hołyst, 2020). Such an approach makes the IPCC-projected temperature highly overestimated if compared with the observational data (Fig. 3). Despite the lockdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020–2021, connected with large cutbacks in transport, travel, industrial production and energy generation, no reduction in atmospheric CO2 was noted. This fact suggests that the proposed reductions in global energy use would be most probably highly ineffective in limiting the level of atmospheric CO2.

Fig. 3. Global estimates of mean annual temperature anomalies (1880–2023), based on land and ocean data (https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/graphs_v4/) and temperature projections to AD 2100 in the successive IPCC reports (1990, 1995, 2001, 2007, 2014, 2021)

Conclusions

The Holocene climate change was characterized by cyclical warmings (such as: Holocene Thermal Maximum, Late Bronze Age, Roman Warm Period, MWP) and coolings (Bond Events: including Iron Age Cold Period, Dark Ages Cold Period and LIA). The IPCC claims that current warming is unprecedented in the last 2000 or even the last 125,000 years; this statement is very unconvincing and it is not supported by the geological data. There is good evidence that both in the last 2000 years as well during the Holocene Thermal Maximum, temperatures were higher or broadly similar to the ones in the current warming period, the Arctic sea ice was less extensive and most mountain glaciers (especially in the northern hemisphere) either disappeared or were smaller. Much stronger summer monsoons in the Early and Middle Holocene made the Sahara green with savanna vegetation, huge lakes and extensive peat bogs. The terms ‘the Holocene Thermal Maximum’ and ‘the Holocene Climatic Optimum’ are avoided by the IPCC (2021), and its popularized statements making the current warming look ‘unprecedented’ and therefore ‘unique’ are false and flatten the climate history (cf. Marcott et al., 2013).

The climate is a product of complicated interdependence of many factors that have not been yet sufficiently recognized qualitatively and quantitatively. It is a great scientific challenge that requires an extensive interdisciplinary research. There is a crucial need to make climate science less political and climate policy more scientific.

4 comments