Kathryn Porter deconstructs the zero carbon mantra in the above video The Electrification Delusion. For those who prefer to read, below is a transcript with my bolds and added images.

The starting point that people make is that we have to decarbonize. They take that position without actually having examined the costs and the benefits of doing that. What’s happening is that our emissions are just moving to somewhere else and are increasing as a result.

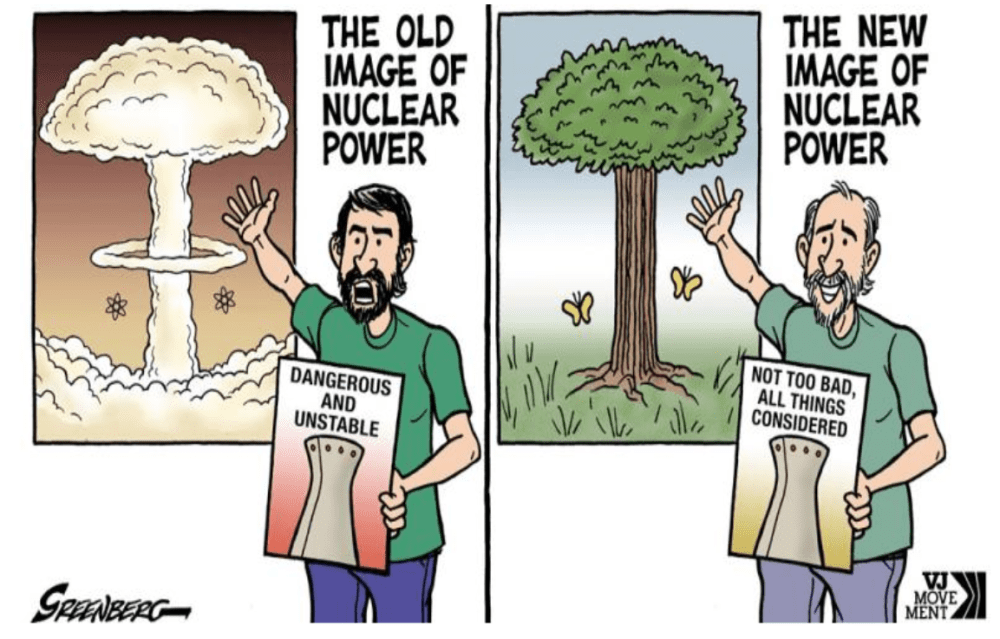

People say, oh, well, nuclear is expensive. It is, but it’s expensive because we chose to make it expensive. We invented a whole load of rules and regulations around it that actually are not useful and not beneficial.

We started subsidizing wind farms in 1990. If they were economic, they would not require subsidies. You hear people like Dale Vince saying, oh, yeah, we should all have renewables or be so much cheaper. And I always ask him on social media, if renewables are so much cheaper, why are ecotricity tariffs higher than the price cap? Never once has he responded to that.

LW: Hello and welcome to this special episode of The Skeptic. I’m your host, Laurie Wostel, an associate editor at The Daily Skeptic.

Now, electrification, can the grid cope? Well, that’s the title of a new report by the independent energy consultant and the woman behind WhatLogic, Kathryn Porter. And I’m very pleased to be joined by her today. So electrification is the big crusade of the policymaking classes, the green blob, as we might call it. Why write this report, Kathryn, and why is it so important for us to know about the impacts of this?

KP: So I was commissioned to write this report. And the brief was to examine what the impact of electrification would be on the British power grid if government targets were met. So, you know, I set out what the targets are. I look at what I think the chances are that they will be met. I look at what the impact on the grid would be if they were met.

I throw in a bit about AI data centres, because although that’s not formally part of electrification, it could have a significant impact on power demand and therefore the state of the grid. And I do a few case studies as well over the European countries. So I looked at Norway, the Netherlands and Germany to see how things are looking there as well.

LW: And so before we get into the specifics of the report, I mean, to begin with, we’re always told, aren’t we, that electrification is going to be this panacea for the economy and the green transition, so-called. Why is it believed to be such an unqualified good?

KP: Well, the starting point that people make is that we have to decarbonise. And they take that position without actually having examined the costs and the benefits of doing that. So there’s a uniform response to anything that has a carbon content, which is we need to get rid of it. But obviously, not all sources of carbon dioxide are equal. And some of the things that you might do instead could turn out to be more harmful than those carbon emitting activities are in the first place.

LW: So, you know, this is why they’re being promoted the way they are, because there’s been a lack of analysis as to, first of all, the extent to which a thing should be decarbonised. It’s just assumed that it should be. And secondly, that the electrification route isn’t more harmful than the original action was in the first place. And so with that justification, there are these extremely ambitious targets, even if in some cases they do keep being pushed back. But I suppose outline for us, Kathryn, how far the green zealots want to go.

KP: Well, I mean, they fundamentally want to electrify everything, but they also want us to reduce our consumption. This tends to be buried in the small print, but you can infer it from the data that are presented. So you have, for example, hidden assumptions within NISO forecasts that suggest we might heat our homes less or travel less. Things that really just don’t have any basis in any sort of evidence and data. Nobody’s ever asked people if they’re willing to travel less or heat their homes less. It was just assumed. Now, NISO has actually rolled back on some of its explicit assumptions in those regards.

But it’s interesting if you look at its future energy scenarios, that it’s not actually consistent across the scenarios on its underlying assumptions of things like comfort levels and distance travelled, which is something of a problem. And it does suggest that the analysis isn’t being done on an equal and fair basis. Certainly when you look at the more recent report they put out in December on the economics of the future energy scenarios, you see them making all sorts of asymmetrical assumptions, very unrealistic cost of capital for things like solar and hydrogen.

They treat the falling behind scenario as a counterfactual when it’s explicitly in the scenarios not a counterfactual. But a lot of the other cost elements are expressed in relation to that scenario rather than on their own basis. It’s just not a fair and even treatment of the analysis.

LW: And then, of course, you have to ask the question, why? Why are they not able to put together a fair and unbiased assessment of cost? And I suppose the answer would be that, well, they can have these grand visions for where we’re supposed to get to. But actually, if you had a proper debate about this, if you really inform the country, you’re going to have to travel less. You’re going to have to heat your home less and so on, then, well, people would start rejecting it.

KP: Yeah, of course. And it would cost more and be less reliable. And also, fundamentally, it might be less good for the environment.

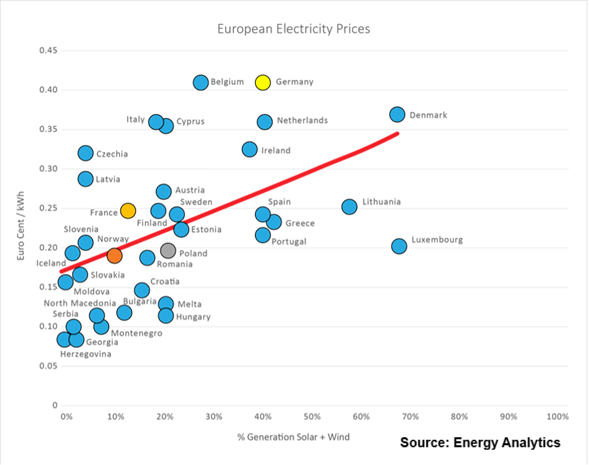

And this is the thing that, you know, one of the worst aspects of it. You look at, for example, the push for renewable generation is making electricity very expensive because this renewable generation is intermittent. You have to create all sorts of backups. It has low energy density. So it has much higher grid costs than the alternatives, as well as using more land. It requires more wires.

It’s intermittent. So it has much higher balancing costs. And all of that makes energy more expensive.

So what’s the outcome of that expensive energy is we have deindustrialisation. So industrial output moves from Britain, not just and that’s bad, not just in terms of the economic impact, but also the environmental impact, because then stuff is being made in countries that have dirtier energy, higher emissions. And you also incur transportation emissions and shipping sort of low value bulk items like steel bars halfway around the world.

It’s actually an incredibly dumb thing to do. But that is the outcome of our energy policy. And so there’s this blind push for a certain objective. Let’s build lots of renewables. We have to decarbonise. But actually, that’s not what’s happening. What’s happening is that our emissions are just moving to somewhere else and are increasing as a result. In the meantime, we are destroying large swathes of other countries, for example, in South America, where we’re mining a lot of the minerals that we need for these transition technologies. And you need huge amounts of metal for renewables.

But wind only works less than a third of the time. The capacity factor for wind is less than 30 percent. Now, the government has higher numbers, but they’re just not borne out by actual real data. I looked at the capacity factors for the past year. They’re about 28 percent on average. So, you know, you’re consuming all of these financial and natural resources for something that works less than a third of the time. And there’s never been any debate about whether that’s actually sensible, whether it’s actually environmentally sustainable or not. And there’s just this assumption that because it’s low carbon, everything else is worse. And I don’t believe that.

I think if you really wanted to have a serious effort at decarbonisation, you would be much more serious about nuclear. And people say, oh, well, nuclear is expensive. It is, but it’s expensive because we chose to make it expensive. We invented a whole load of rules and regulations around it that actually are not useful and not beneficial. We should be doing the way South Korea does it, which is faster and vastly cheaper. They’ve built their reactors. They’ve got eight of them now, four in South Korea, four in UAE, at an average cost of five to six billion U.S. dollars. Hinkley Point is going to cost us about 32 billion pounds. So it’s multiples cheaper to build it the way the Koreans are doing.

We could do it in the same way. Certainly on the nuclear side, there’s a few issues around sort of employment rights that would be a little bit different, but that wouldn’t have that much cost or additional time. They’re also building them in eight and a half years, you know, and we’re taking two decades.

This is just it’s a self-inflicted wound. We don’t have to do it that way. We could do it the same way that they do at the same cost and in the same time frames. We just choose not to. So there’s nothing fundamentally, inherently expensive about nuclear. It’s just the way that we do it.

LW: And Kathryn, why is it working so badly?

Oh, well we create all sorts of unnecessary complexities like the fish disco at Hinkley, for example. EDF has got to spend millions of pounds to prevent the deaths of half a trawler’s worth of fish every year. I mean, that’s insane. In the fishing industry, they throw more than that amount of fish back in the sea every year. Just because it’s being killed as a nuclear site doesn’t mean it’s any different outcome for the fish. And also people are more important than fish.

If you look at what the way they treat worker radiation exposure, each new plant is supposed to have a lower worker radiation exposure level than the last one. And that sounds very nice in theory, you know, continuing improvements. But the old advanced gas cooled reactors that are coming to end of life have lower internal radiation levels than you have outside on the street.

So workers going to work in that plant get more radiation exposure in the car park than they do inside the plant. So then what’s the useful benefit of reducing that exposure further? All it does is create costs and engineering challenges that are difficult to solve and pointless. Because if the workers get more radiation exposure in the car park, then, you know, and they can’t.

It’s just it’s just a nonsense. And it just makes everything expensive because somebody on paper thought, oh, yeah, that sounds great. We’ll have a continuing improvement. But they don’t think about what it means in real life. And when you think in terms of what it means in real life, you think, no, that doesn’t make any sense and we shouldn’t do it. And so it’s all these types of things that have crept in over the years when nuclear wasn’t a priority.

The nuclear regulator has an objective to reduce deaths from radiation. Well, you can easily do that by closing all your nuclear reactors and not building any new ones. But that kind of defeats the purpose.

So we need to get away from this risk avoidance mindset. We shouldn’t be seeking to avoid risk. We should be seeking to manage risk in an appropriate way. Lowering the radiation inside the plant to a level lower than on the street outside is not sensible.

LW: And to bring us back to the central contradiction here and muddled thinking. I mean, you’ve mentioned that in terms of nuclear and in terms of where the emissions are going, the total amount of them in the world. But of course, the central one really seems to be that, well, actually, we’re going to be switching over to electricity. We’re going to be electrifying everything, electric cars and all these new technologies at the same time that we’re actually making electricity much, much more expensive. I mean, it’s mad, isn’t it?

KP: It is. We’re making electricity more expensive and less reliable. The cost element is an obvious deterrent to electrifying your heating and transports. And, you know, some of the people who’ve seen my reports, they say, oh, well, I have an electric car and I can charge it at home and it’s way cheaper. Well, well, lucky you. But that’s not the reality for a lot of people. They’re like, oh, yeah, well, I have a heat pump and it works just fine in the winter. Again, lucky you. Right. You probably have a well insulated house. Other people don’t.

So my report looks at what’s correct and true on average, not in specific cases. Anecdotes and data are not the same thing. And unfortunately, too many people critiquing my report are confused between what’s data and what’s an anecdote. And if you look at the data, which is what I do look at in my report, you can see that in most cases it’s more expensive to own an electric car than it is to own a conventional car. And it’s more expensive to own a heat pump than it is to have a gas boiler.

And so these are the facts that the data show. And just because for some people, some people, that’s not the case doesn’t mean it’s not true overall. In the same way, if it was genuinely cheaper to have an electric car, don’t you think that people would just go buy electric cars? You wouldn’t need to have subsidies and mandates and penalise car makers for not selling enough electric cars.

Just a couple of days ago, somebody senior at Volkswagen, I think, or Vauxhall, was saying that there’s just no natural demand for electric cars. It’s not a product that people want to buy. They only buy it through compulsion or subsidy. So if electric cars were desirable and cheaper because cost is something that’s obviously a big motivator for people, then you wouldn’t need to have subsidies or compulsion. People would just go and buy this stuff and they don’t.

Look at wind farms. We’re just signing up new subsidies for wind farms that are not only more expensive than the previous ones, but are now going to be for 20 years. We started subsidising wind farms in 1990 and we’re now offering 20 year subsidies after 35 years of subsidising. We’re now going to offer them 20 year subsidies locking in. So that’ll be more than half a century of subsidies for wind farms. If they were economic, they would not require subsidies. Right.

So all of this just makes energy more expensive and less reliable and less appealing for people. It’s very model thinking. And it’s what happens when you put ideology ahead of data.

So all of this just makes energy more expensive and less reliable and less appealing for people. It’s very model thinking. And it’s what happens when you put ideology ahead of data.

LW: And so you mentioned the subsidies. We very recently had allocation round seven of the contracts of difference for renewables generation over the coming years. How did that go? Was it looking good for Ed Miliband and his claims to be bringing down energy bills?

KP: No, it’s the exact opposite. So £94 is where it cleared for offshore wind for 20 year contracts. So last year it cleared £83 for 15 year contracts. So if you were to transpose that £94 onto a 15 year basis, it would probably be around £104. So you should be comparing the £104 with the 83 from last year. Now, last year, Orsted cancelled Hornsea 4, which was the flagship project and by far the biggest volume component of AL6. They cancelled it because £83 wasn’t enough.

They said the economics weren’t good enough. So now you’ve had AL7 coming in at a much, much higher price and for 20 years. So now that’s locking in this high level of cost for 20 years. So it doesn’t matter what happens to wholesale prices. These wind farms will get guaranteed index linked £94 per megawatt hour for the next two decades or for the two decades after when they open.

LW: And just remind us, how does that compare with gas at the moment?

KP: OK, so the wholesale cost of generating gas in 2025 was £80 per megawatt hour. But although we saw a reduction in gas prices, we saw carbon prices more than doubled. And so carbon prices went from being about 11% of the wholesale price a year ago to now being about 28%. And this is because Keir Starmer wants to harmonise UK and European carbon prices. So they’re almost harmonised now.

But there’s been this huge increase in carbon costs over the past year. As I said, it’s more than doubled.

It was £35 a megawatt hour a year ago and now it’s around 73. So even with all this playing around with the prices, the underlying cost would be considerably cheaper if we were all on gas. The underlying cost would be far cheaper if we were all on gas and didn’t have carbon taxes.

Because the carbon taxes don’t achieve anything. When there was a choice between gas and coal, which was more carbon intensive, you could argue there was some point to it. But there’s no point to it now.

Nobody’s switching to renewables because of carbon taxes. First of all, nobody chooses renewables on their tariff. There’s a small number of 100% so-called 100% green tariffs. They are actually more expensive than the price cap. So you hear people like Dale Vince saying, oh, yeah, we should all have renewables, it’ll be so much cheaper. And I always ask him on social media, if renewables are so much cheaper, why are ecotricity tariffs higher than the price cap? Never once has he responded to that.

LW: Now, Kathryn, you’re, of course, an expert on all this. But was there anything that surprised you as you were carrying out the report that you hadn’t known before?

KP: I was a little bit surprised at the magnitude of the risk within the generation fleet. I think everybody knows that we’ve got the advanced gas called reactors will be closing. That’s just under five gigawatts. Now we’ve obviously got Hinkley Point going to open and I think we’ll probably have some new gas generation opening. So that will offset the nuclear closures that we’re going to see.

But nobody’s really talking about the risks of the gas fleet. Now, NISO, the system operator, says that it expects we should have all 32 gigawatts of the existing gas fleet available to run in 2030 under the Clean Power Plan. But it only thinks it’ll run 5% of the time. Now, the trouble with that is that there’s probably about 12 gigawatts of that 32, which is at risk of closing in the next five to seven years. A third of the gas fleet was built in the 1990s. Another third was built in the 2000s.

And a lot of those assets haven’t really had the type of upgrades and so on that would really extend their lives. So these and some of them are showing really degraded reliability. So the idea that you will keep all of these assets on the grid into the next decade just seems a bit far-fetched to me.

And the other problem is that 5% utilization is just not how these assets were designed to be run. They were actually designed to run baseload. So baseload is extremely rare. Nobody really runs baseload for a gas plant now. They do what’s called two-shifting or they don’t run at all. And two-shifting means that they fire up in the morning and then they go off overnight. Now, if you don’t run your CCGT for a couple of weeks, you start getting all sorts of operational problems with them that are difficult to solve. So the idea that you’re going to take end-of-life assets that were designed to run in a particular way, baseload, and expect them to run only 5% of the time and that they actually will all run when you need them, to me, it’s for the birds. This is just not realistic.

Any old asset is going to have a risk of not turning on when you need it. And when are we going to need it? We’re going to need it on cold winter days when it’s not windy. So in the winter, during our peak demand, there is no contribution from solar at all. It is zero. The sun sets around 4 p.m. Peak demand is at 6 p.m. So there is no sun in the winter peak. And it’s astonishing how few people realize this. And even during the day, it can be almost nothing at lunchtime. But in the evening peak, there is literally nothing because it’s at nighttime. So zero solar contribution to energy security in winter.

Number two, wind can be almost nothing as well. Wind can go down to megawatts. So if you have to meet 50 gigawatts of demand, which we had the other week, it peaks at 51 in the cold weather a couple of weeks ago, and you’ve got no wind and you’ve got no solar, and you’re relying on your old gas power stations that haven’t maybe fired up for a couple of weeks, what are the chances that not enough of them come on when you need them to? And if that happens, we’ll just have blackouts. If we know it’s going to happen, we’ll ration.

And if we don’t know it’s going to happen, it’ll be a blackout. And we saw in Iberia, 11 people died, and that was really benign weather conditions. So I think a winter blackout in Britain, particularly an unscheduled one, would be significantly more dangerous. So my whole report really says that we should not be complacent about these risks. We need to recognise that these assets might close.

And the reality is right now, the lead times for either extending the lives of these plants or replacing them is long, because the supply chains are very constrained. So if you want a new gas turbine, that’s seven to eight years, a new rotor is about five years. Even the equipment that you’d use for major maintenance is about a year and a half to come to site. So we don’t have that much time to act. We need to be ordering this equipment now to be sure that it’ll be in place when we need it.

But nothing’s happening. There isn’t a plan for this. And there are other risks as well. We have risks around our transmission infrastructure and our distribution infrastructure, old equipment on the grid that’s not being replaced at the rate that it potentially needs to be replaced.

We have serious risks with our offshore gas infrastructure where we might have shortages of gas. Now, NISO put out a report in November, actually published the same day of the autumn budget, so it didn’t really get much attention, saying that some of these offshore pipeline systems are at risk of closure because there’s not enough gas going through them. And if that happens, we won’t have enough gas on cold winter days to meet demand unless we do something about it.

So what are the things we can do about it? One is, well, don’t prematurely close down the North Sea. So if you reverse the ban on drilling and you relax the fiscal regime to make it more accommodating, we could keep producing much more oil and gas than we currently expect. And that would extend the lives of these pipelines.

The other alternative is to put in floating liquefied natural gas regasification terminals. This is what Germany did. You can do it reasonably quickly, but not overnight. It will still take you a couple of years, really, potentially to do that, because even if you’ve got the entry capacity onto the gas network, which we do have at a couple of places around the coast, you still need to build the ship handling. You need to build storage tanks. There’s going to be additional pipe infrastructure that you need to build.

So it’s not something that you can just do just like that overnight. It takes time. And so this is the concern I have, is that we have all of these risks, but we’re not factoring in the time that could be needed to actually address them. And if we run out of time, then we will have an insecure system.

LW: Indeed. And so finally, then, do you think that the political class are waking up to these realities at all?

KP: Well, as for political class, it depends. Right. So you look at the conservatives. Claire Coutinho had a plan to build more gas power stations under the previous conservative government. Labour ditched it. So both the conservatives and reform. And I think realistically, one of those two parties will form the next government. And they both want to take a different approach on net zero, a much more pragmatic approach. And neither of them really, to my understanding, is saying, oh, let’s just, you know, just kill the environment. We don’t care about the environment at all.

What they’re saying is we need a more measured approach and that people are more important. And so it’s counterproductive if you push people into poverty or if you harm them through energy and security and put their lives at risk. These things are not better than the risk that they might face through climate change.

So it has to be a balanced approach that examines the costs and benefits of different types of actions. And the trouble is, at the moment, what we have is an ideology that says that the worst evil that anybody can imagine is carbon dioxide. And that must be removed at all costs.

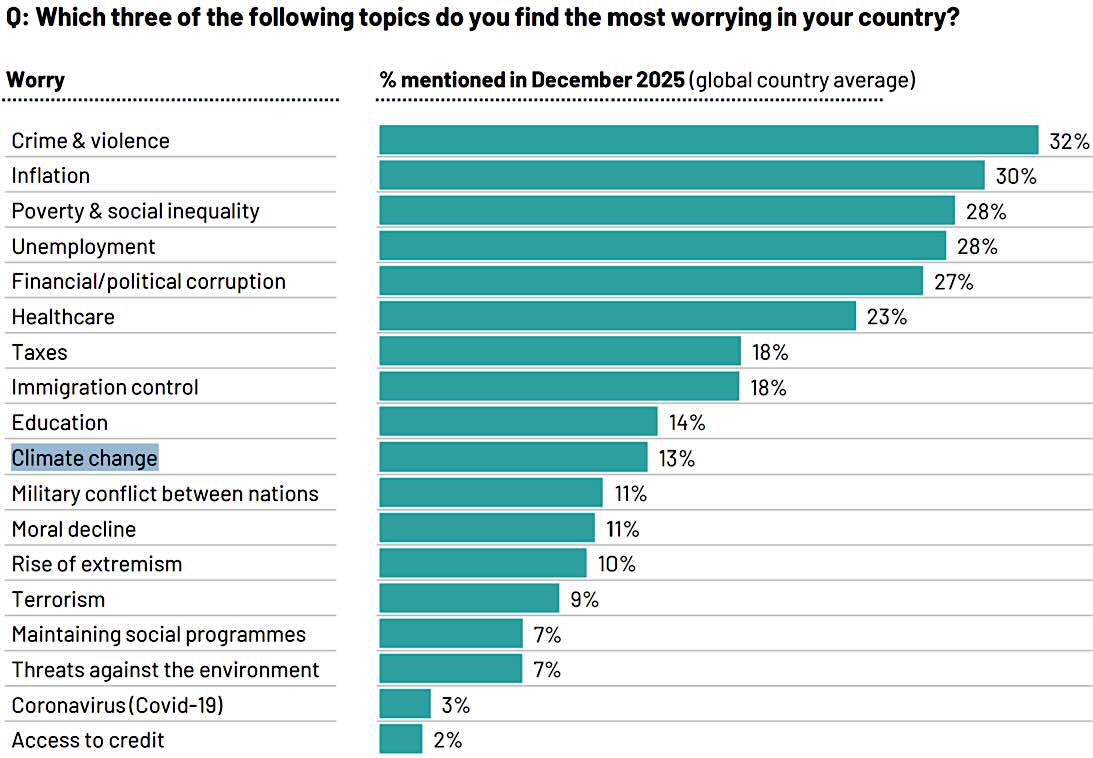

But this is not correct. It’s not democratic. The public hasn’t ever said that’s what they want. And because this has never been laid out to them. And if you ask people, do they want to do something about the environment? They say yes. But if you ask them how much they’re willing to spend on it, then they say something ridiculous like 10 pounds a year or something completely unrealistic.

So there’s a democratic deficit here. This actually has some commonalities with Brexit or with EU membership, where, you know, there was certainly a section of people that felt that there’d been a democratic deficit there. And this is and I think this is one of the arguments that Nigel Farage makes, that there’s a similar democratic deficit around net zero to what there was around EU membership.

Not that I want to get into the Brexit debate, but when people feel that their views haven’t been sought and that things have been imposed on them and that those things worsen their quality of life, then they tend to get upset about it. And I think that’s why we’re seeing some of the pushback is when people see that their energy is getting more expensive. They can see it’s getting less reliable. They can see they’re being pushed into things they don’t want, like electric cars and heat pumps that will degrade for the most part their quality of life. And nobody ever asked them if that was a good thing.

See Also Synopsis of Porter’s Report

Don’t worry about warming, just read a good book or two and relax! Since the Little Ice Age, warming has been unequivocally beneficial. and we are still a degree or three short of the Roman Warm Period which was the best time on earth for living things.

Moreover, we are losing the war on CO2!

https://rafechampion.substack.com/p/losing-the-war-on-co2

Fear of warming and CO2 has driven the most damaging public policy blunder on record, with trillions of dollars wasted around the western world on the attempt to transition to intermittent wind and solar power.

Would you spend a single dollar to get the results of this great experiment?

Electricity costs have doubled or tripled in some places. The supply is less secure, with blackouts looming in Germany, Britain, and Australia. The current is less stable in voltage and frequency, which are vital for modern manufacturing machinery.

And the environmental carnage!

From the overseas mines to the cancerous proliferation of wind and solar facilities carving up our forests and farmlands, to the impending tsunami of toxic waste when the hardware has to be thrown away and replaced.

LikeLike