Top Climate Model Improved to Show ENSO Skill

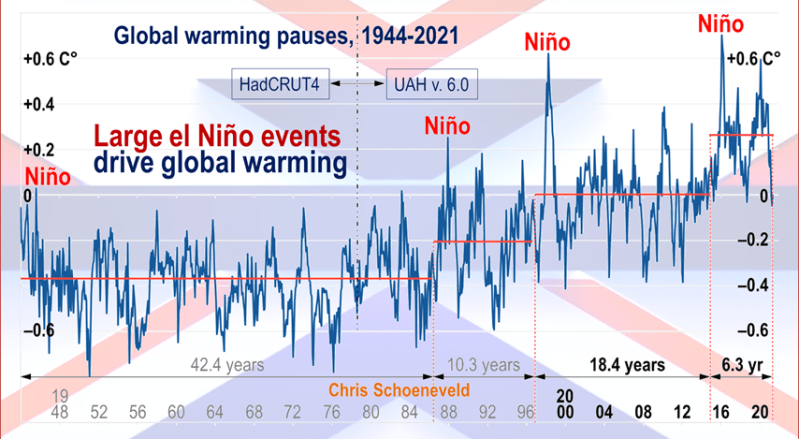

Previous posts (linked at end) discuss how the climate model from RAS (Russian Academy of Science) has evolved through several versions. The interest arose because of its greater ability to replicate the past temperature history. The model is part of the CMIP program which is now going the next step to CMIP7, and is one of the first to test with a new climate simulation. Improvements to the latest model, INMCM60, show an enhanced ability to replicate ENSO oscillations in the Pacific ocean, which have significant climate impacts world wide.

This news comes by way of a new paper published in the Russian Journal of Numerical Analysis and Mathematical Modelling February 2024. The title is ENSO phase locking, asymmetry and predictability in the INMCM Earth system model, Seleznev et al. (2024) Excerpts in italics with my bolds and images from the article.

Abstract:

Advanced numerical climate models are known to exhibit biases in simulating some features of El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) which is a key mode of inter-annual climate variability. In this study we analyze how two fundamental features of observed ENSO – asymmetry between hot and cold states and phase-locking to the annual cycle – are reflected in two different versions of the INMCM Earth system model (state-of-the-art Earth system model participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project).

We identify the above ENSO features using the conventional empirical orthogonal functions (EOF) analysis which is applied to both observed and simulated upper ocean heat content (OHC) data in the tropical Pacific. We obtain that the observed tropical Pacific OHC variability is described well by two leading EOF-modes which roughly reflect the fundamental recharge-discharge mechanism of ENSO. These modes exhibit strong seasonal cycles associated with ENSO phase locking while the revealed nonlinear dependencies between amplitudes of these cycles reflect ENSO asymmetry.

We also assess and compare predictability of observed and simulated ENSO based on linear inverse modeling. We find that the improved INMCM6 model has significant benefits in simulating described features of observed ENSO as compared with the previous INMCM5 model. The improvements of the INMCM6 model providing such benefits arediscussed. We argue that proper cloud parametrization scheme is crucial for accurate simulation of ENSO dynamics with numerical climate models

Introduction

El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the most prominent mode of inter-annual climate variability which originates in the tropical Pacific, but has a global impact [41]. Accurately simulating ENSO is still a challenging task for global climate modelers [3,5,15,25]. In the comprehensive study [35] large-ensemble climate model simulations provided by the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phases 5 (CMIP5)and 6 (CMIP6) were analyzed. It was found that the CMIP6 models significantly outperform those fromCMIP5 for 8 out of 24 ENSO-relevant metrics, especially regarding the simulation of ENSO spatial patterns, diversity and teleconnections. Nevertheless, some important aspects of the observed ENSO are still not satisfactorily simulated by the most of state-of-the-art models [7,38,49]. In this study we are aimed at examination of how two such aspects – ENSO asymmetry and ENSO phase-locking to the annual cycle –are reflected in the INMCM Earth system model [44, 45].

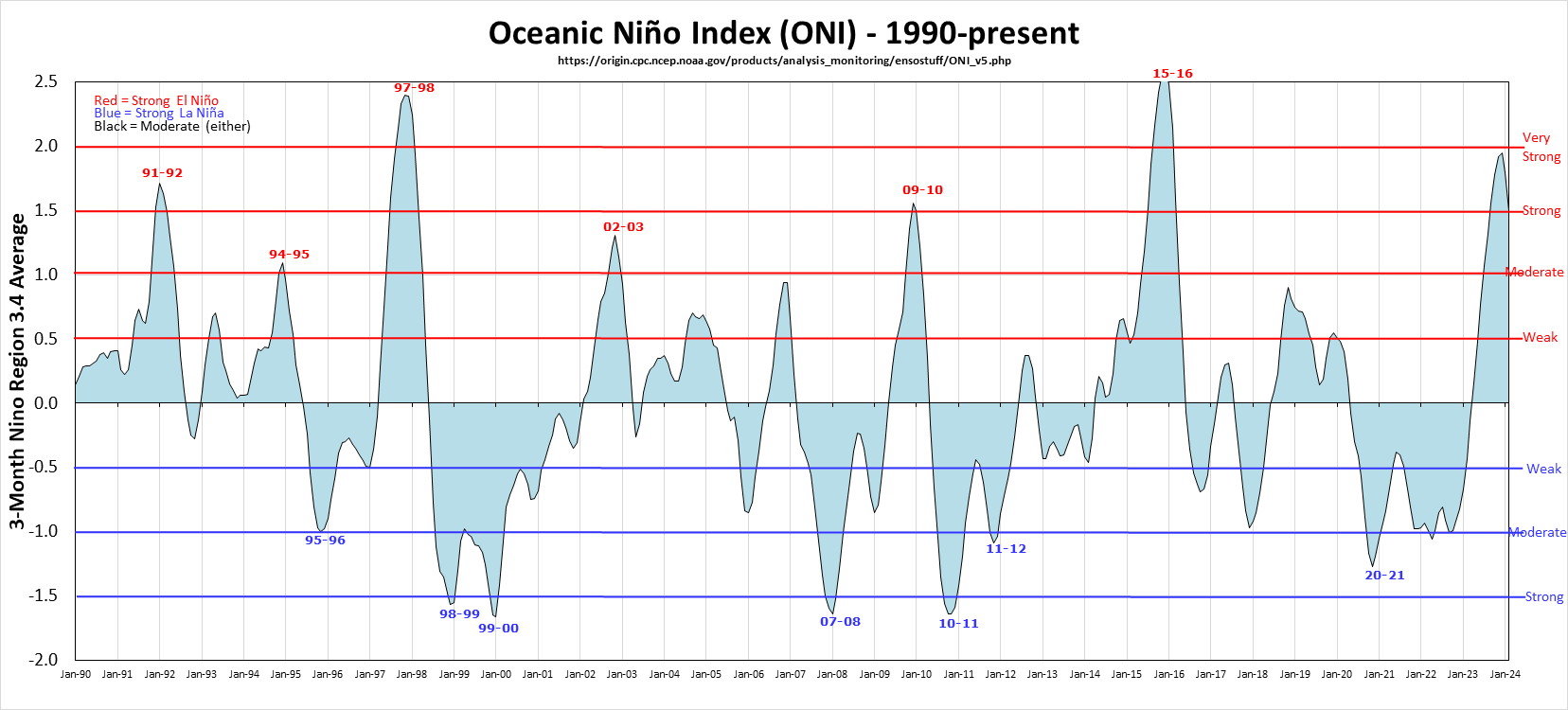

The asymmetry between hot (El Nino) and cold (La Nina) states is a fundamental feature in the observed ENSO occurrences [39]. El Niño events are often stronger than La Niña events, while the latter ones tend to be more persistent [10]. Such an asymmetry is generally attributed to nonlinear feedbacks between sea surface temperatures (SSTs), thermocline and winds in the tropical Pacific [2,19,28]. The alternative conceptions highlight the role of tropical instability waves [1] and fast atmospheric processes associated with irregular zonal wind anomalies [24]. ENSO phase-locking is identified as the tendency of ENSO-events to peak in boreal winter.

Several studies [11,17,34] argue that the phase-locking is associated with seasonal changes in thermocline depth, ocean upwelling velocity, and cloud feedback processes. These processes collectively contribute to the coupling strength modulation between ocean and atmosphere, which, in the context of conceptual ENSO models [4,18], provides seasonal modulation of stability (in the sense of decay rate) of the “ENSO oscillator”. Another theory [20,42] supposes the phase-locking results from nonlinear interactions between the seasonal forcing and the inherent ENSO cycle. Both the asymmetry and phaselocking effects are typically captured by low-dimensional data-driven ENSO models [14, 21, 26, 29, 37].

In this work we identify the ENSO features discussed above via the analysis of upper ocean heat content (OHC) variability in the the tropical Pacific. The recent study [37] analyzed high-resolution reanalysis dataset of the tropical Pacific (10N – 10S, 120E – 80W) OHC anomalies in the 0–300 m depth layer using the standard empirical orthogonal function (EOF) decomposition [16]. It was found that observed OHC variability is effectively captured by two leading EOFs, which roughly describe the fundamental recharge-discharge mechanism of ENSO [18]. The time series of the corresponding principal components (PCs) demonstrate strong seasonal cycles, reflecting ENSO phase-locking, while the revealed inter-annual nonlinear dependencies between these cycles can be associated with ENSO asymmetry [37].

Here we apply similar analysis to the OHC data simulated by two different versions of INMCM Earth system model. The first is the INMCM5 model [45] from CMIP6, and the second is the perspective INMCM6 [44] model with improved parameterization of clouds, large-scale condensation and aerosols. Along with the traditional EOF decomposition we invoke the linear inverse modeling to assess and compare predictability of ENSO from observed and simulated data.

The paper is organized as follows. Sect. 2 describes the datasets we analyze: OHC reanalysis dataset and OHC data obtained from the ensemble simulations of global climate with two versions of INMCM model. Data preparation, including separation of the forced and internal variability, is also discussed. The ensemble EOF analysis is represented, which is used for identifying the meaningful processes contributing to observed and simulated ENSO dynamics. Sect. 3 presents the results we obtain in analyzing both observed and simulated OHC data. In Sect. 4 we summarize and discuss the obtained results, particularly regarding the significant benefits of new version of INMCM model (INMCM6) in simulating key features of observed ENSO.

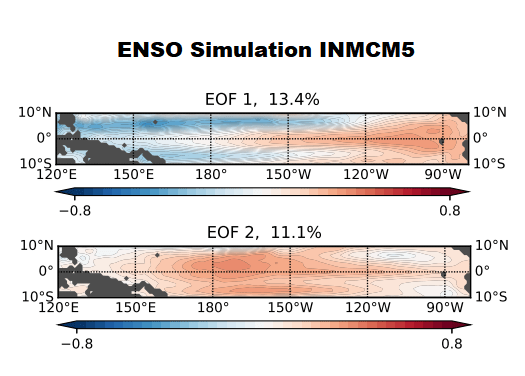

Fig. 2: Two leading EOFs of the INMCM5 ensemble of tropical Pacific upper ocean heat content simulations

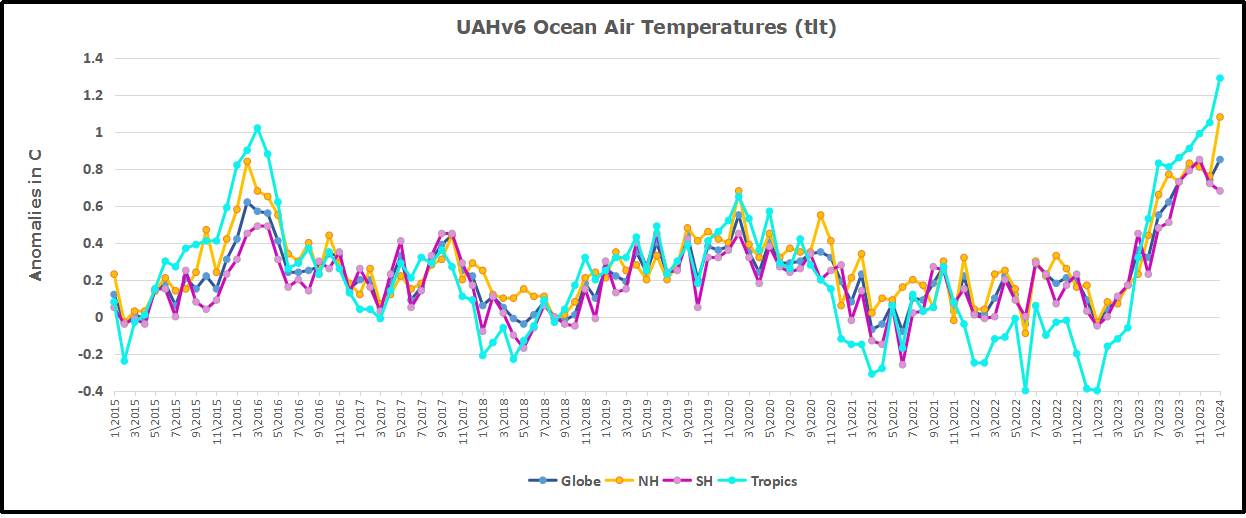

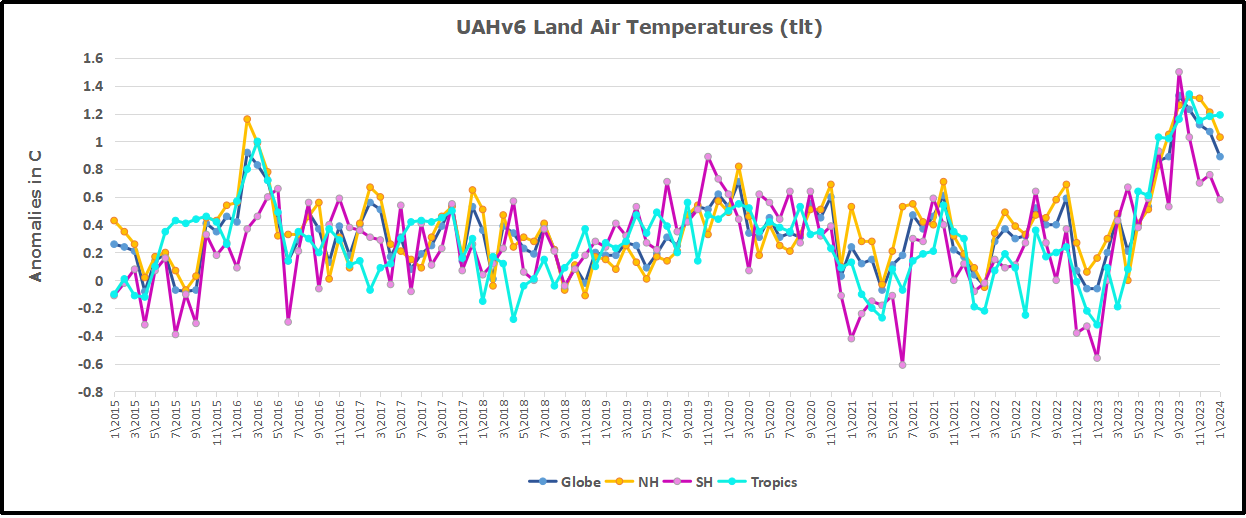

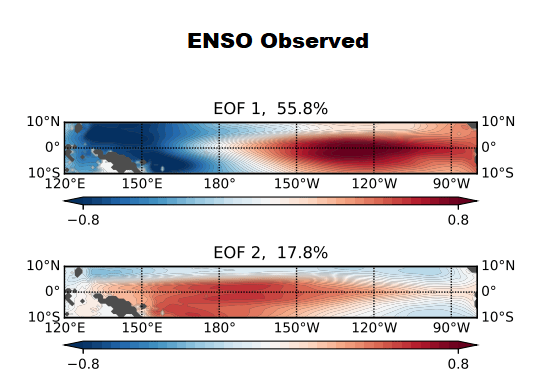

The corresponding spatial patterns in Fig. 1 have clear interpretation. The first contributes to the central and eastern tropical Pacific, where most significant variations of sea surface temperature (SST) during El Niño/La Nina events occur [9]. The second predominates mainly in the western tropical Pacific and can be associated with the OHC accumulation and discharge before and during the El Niño events [48].

What we can see from Fig. 2 is that the two leading EOFs of OHC variability simulated by the INMCM5 model do not correspond to the observed ones. The corresponding time series and spatial patterns exhibit smaller-scale features, as compared to those we obtain from the reanalysys data, indicating their noisier spatio-temporal nature.

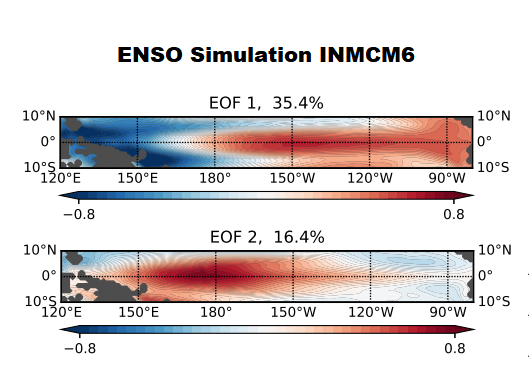

The two leading EOFs of the improved INMCM6 model (Fig. 3), by contrast, capture well both the spatial and temporal features of observed EOFs. In the next section we focus on furtheranalysis of these EOFs assuming that they contain the most meaningful information about ENSO dynamics.

Discussion

In this study we have analyzed how two different versions of the INMCM model [44,45] (state-of-the-art Earth system model participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, CMIP) simulate some features of El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) which is a key mode of the global climate. We identified the ENSO features via the EOF analysis applied to both observed and simulated upper ocean heat content(OHC) variability in the the tropical Pacific. It was found that the observed tropical Pacific OHC variability is captured well by two leading modes (EOFs) which reflect the fundamental recharge-discharge mechanism of ENSO involving a recharge and discharge of OHC along the equator caused by a disequilibrium between zonal winds and zonal mean thermocline depth. These modes are phase-shifted and exhibit the strong seasonal cycles associated with ENSO phase locking. The inter-annual dependencies between amplitudes of the revealed ESNO seasonal cycles are strongly nonlinear which reflects the asymmetry between hot (ElNino) and cold (La Nina) states of observed ENSO. We found that the INMCM5 model (the previous version of the INMCM model from CMIP6) poorly reproduces the leading modes of observed ENSO and reflect neither the observed ENSO phase locking nor asymmetry. At the same time, the perspective INMCM6 model demonstrates significant improvement in simulating these key features of observed ENSO. The analysis of ENSO predictability based on linear inverse modeling indicates that the improved INMCM6 model reflects well the ENSO spring predictability barrier and therefore could potentially have an advantage in long range weather prediction as compared with the INMCM5.

Such benefits of the new version of the INMCM model (INMCM6) in simulating observed ENSO dynamics can be provided by using more relevant parametrization of sub-grid scale processes. Particularly, the difference in the amplitude of OHC anomaly associated with ENSO between INMCM5 and INMCM6 shown in Fig.2-3 can be explained mainly by the difference in cloud parameterization in these models. In short, in INMCM5 El-Nino event leads to increase of middle and low clouds over central and eastern Pacific that leads to cooling because of decrease in surface incoming shortwave radiation.

While decrease in low clouds and increase in high clouds in INMCM6 over El-Nino region during positive phase of ENSO lead to further upper ocean warming [43]. This is consistent with the recent study [36] which argued that erroneous cloud feedback arising from a dominant contribution of low-level clouds may lead to heat flux feedback bias in the tropical Pacific, which play a key role in ENSO dynamics. Fast decrease in OHC in central Pacific after El-Nino maximum in INMCM6 can probably occur because of too shallow mixed layer in equatorial Pacific in the model, that leads to fast surface cooling after renewal of upwelling and further increase of tradewinds. Summarizing the above we can conclude that proper cloud parameterization scheme is crucial for accurate simulation of observed ENSO with numerical climate models.

Background on INMCM6

The INMCM60 model, like the previous INMCM48 [1], consists of three major components: atmospheric dynamics, aerosol evolution, and ocean dynamics. The atmospheric component incorporates a land model including surface, vegetation, and soil. The oceanic component also encompasses a sea-ice evolution model. Both versions in the atmosphere have a spatial 2° × 1° longitude-by-latitude resolution and 21 vertical levels up to 10 hPa. In the ocean, the resolution is 1° × 0.5° and 40 levels.

The following changes have been introduced into the model compared to INMCM48.

Parameterization of clouds and large-scale condensation is identical to that described in [4], except that tuning parameters of this parameterization differ from any of the versions outlined in [3], being, however, closest to version 4. The main difference from it is that the cloud water flux rating boundary-layer clouds is estimated not only for reasons of boundary-layer turbulence development, but also from the condition of moist instability, which, under deep convection, results in fewer clouds in the boundary layer and more in the upper troposphere. The equilibrium sensitivity of such a version to a doubling of atmospheric СО2 is about 3.3 K.

The aerosol scheme has also been updated by including a change in the calculation of natural emissions of sulfate aerosol [5] and wet scavenging, as well as the influence of aerosol concentration on the cloud droplet radius, i.e., the first indirect effect [6]. Numerical values of the constants, however, were taken to be a little different from those used in [5]. Additionally, the improved scheme of snow evolution taking into account refreezing and the calculation of the snow albedo [7] were introduced to the model. The calculation of universal functions in the atmospheric boundary layer in stable stratification has also been changed: in the latest model version, such functions assume turbulence at even large gradient Richardson numbers [8].

fWhen the above material, stressing the need to examine the total picture in any critical thinking, was shown to a high school Principal, to a high school science teacher and to an environmental engineer, they were all surprised and quite critical that one would want to show this to students. Annoyed actually. One was emphatic…

fWhen the above material, stressing the need to examine the total picture in any critical thinking, was shown to a high school Principal, to a high school science teacher and to an environmental engineer, they were all surprised and quite critical that one would want to show this to students. Annoyed actually. One was emphatic…