A recent paper in the journal Atmosphere draws together contemporary findings into a new and wholistic paradigm for the workings of earth’s climate system. Stuart Harris published Comparison of Recently Proposed Causes of Climate Change. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

Abstract

This paper compares the ideas contained in the main papers published on climate change since World War II to arrive at a suggested consensus of our present knowledge regarding climatic changes and their causes.

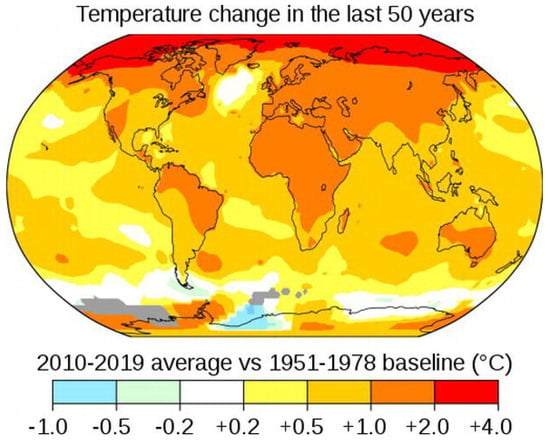

Atmospheric carbon dioxide is only suggested as a cause in one theory, which, despite its wide acceptance by Politicians, the media, and the Public, ignores the findings in other studies, including the ideas found in the Milankovitch Cycles. It also does not explain the well-known NASA map of the changes between the global 1951–1978 and the 2010–2019 mean annual temperatures.

The other theories by Oceanographers, Earth scientists, and Geographers fit together to indicate that the variations in climate are the result of differential solar heating of the Earth, resulting in a series of processes redistributing the heat to produce a more uniform range of climates around the surface of the Earth. Key factors are the shape of the Earth and the Milankovitch Cycles, the distribution of land and water bodies, the differences between heating land and water, ocean currents and gateways, air masses, and hurricanes.

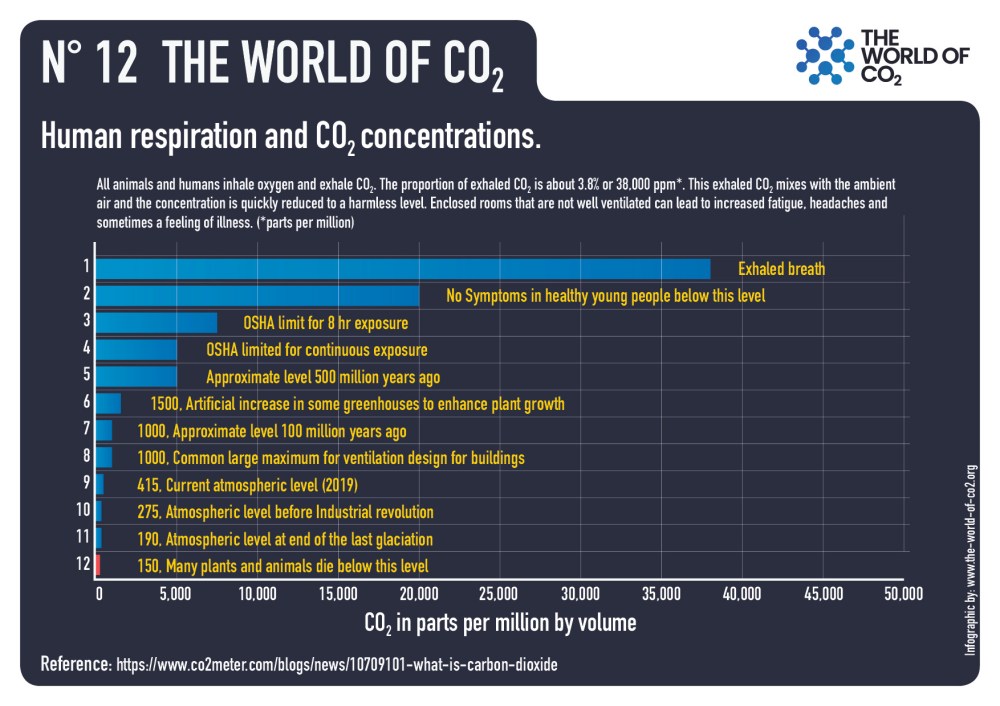

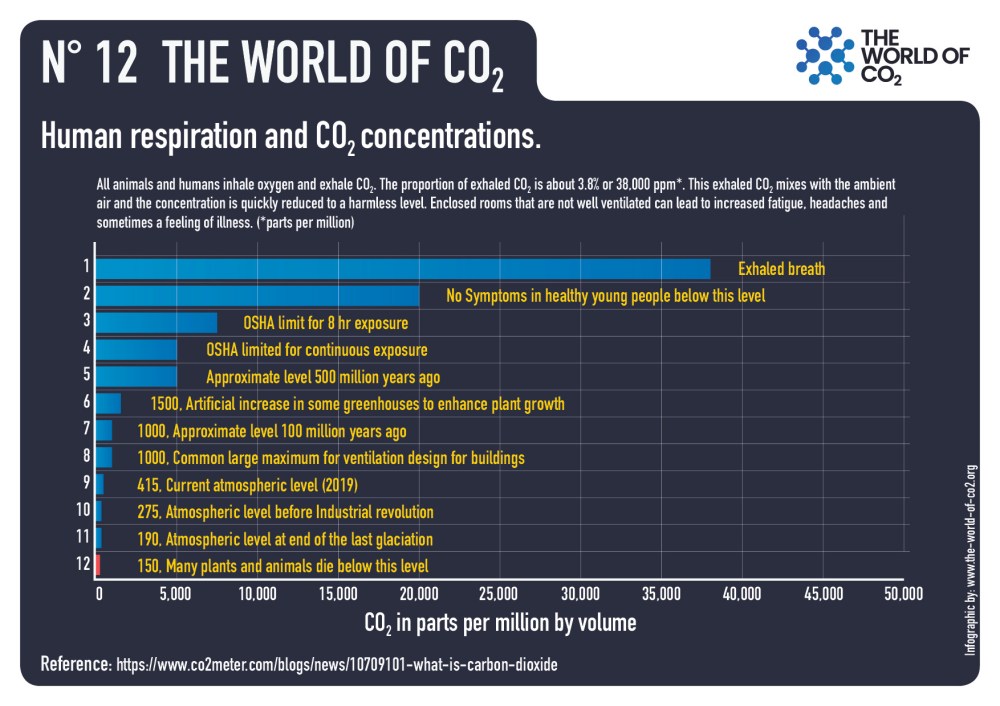

Low atmospheric carbon dioxide levels during cold events could result in too little of this gas to support photosynthesis in plants, resulting in the extermination of most life on Earth as we know it. The 23 ka Milankovitch cycle has begun to reduce the winter insolation received at the surface of the atmosphere in the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere starting in 2020. This results in extreme weather as the winter insolation reaching the surface of the atmosphere in the higher latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere decreases while the summer air temperatures increase. It heralds the start of the next glaciation.

A brief outline is given of some of the climatic changes and consequences that may be expected in western Canada during the next 11.5 ka.

Discussion

To make progress in Climatology, it has been shown that a good, reliable database of the constituent properties of the climate is necessary to obtain a reasonable average for that time slice. The difficulty is coping with the tremendous variation in conditions over the entire Earth at all time scales. The data should also be complete and obtained by a consistent method of measurement for all stations. Ideally, there should be no breaks in the data, although this is not usually achieved. Changes in methodology, equipment, and storage of large volumes of data have been major problems. As a result, most scientists studying the subject work with models of meteorology and weather forecasting.

2. New Data on the Mechanism of Global Warming

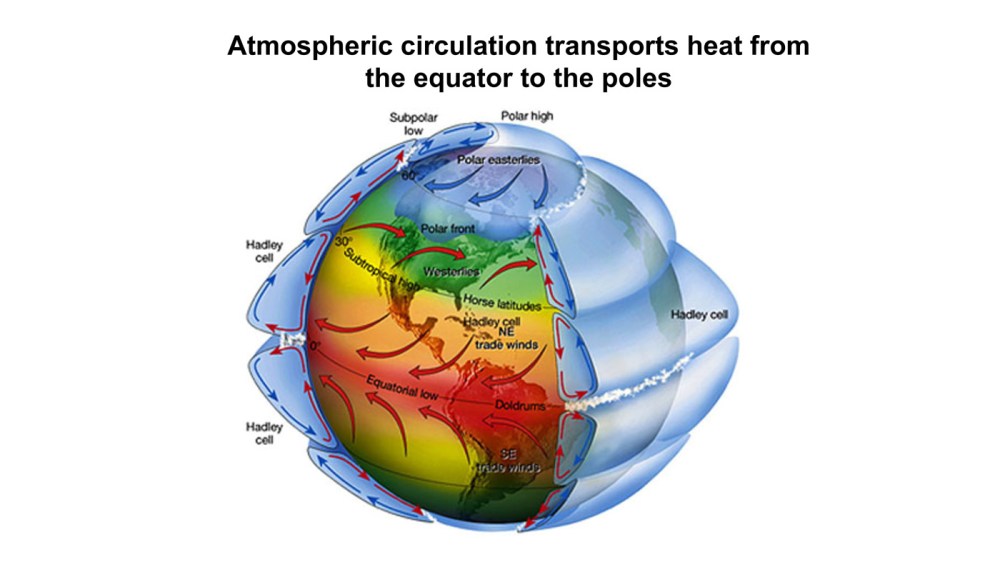

It is now known that solar radiation supplies more than 99.95% of the total energy driving the world’s climate [7]. The fact that the bulk of the solar radiation arrives on the surface of the Earth along the zone between the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer, decreasing towards the Poles, results in a tremendous imbalance of initial heat distribution around the globe. The amount of solar heating at the polar latitudes throughout the year varies greatly, with the polar latitudes receiving considerably more solar energy in the summer than in the winter, when they receive no solar heat at all. As a result, in the winter hemisphere, the difference in solar heating between the equator and that pole is very large. This causes the large-scale circulation patterns observed in the atmosphere in the northern hemisphere. The difference in solar heating between day and night also drives the strong diurnal cycle of surface temperature over land.

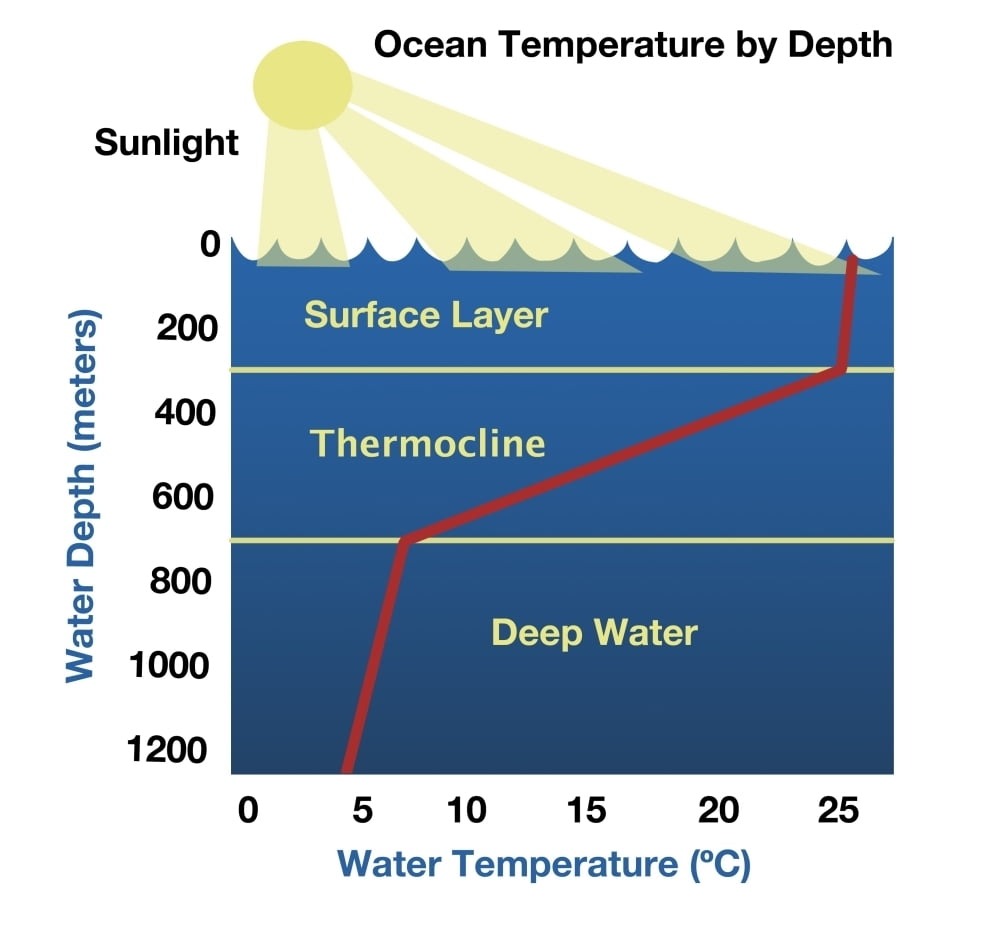

2.1. Thermal Properties of the Earth’s Surface

A total of 70% of the Earth’s surface consists of water, with the remainder being land (rock, soil, or ice). The albedo of ice ranges from 0.5 to 0.7, so ice- and snow-covered surfaces reflect much of the incoming solar radiation back into space. Water has a very high heat capacity (4.187 mJ/m3 K), so it can store or transport large quantities of heat in a given volume of water [8]. In addition, it absorbs over five times as much heat as soil or rock since it is translucent [9,10]. Currents, convection, and wave action mix the water, whereas transmission into a rock or sediment must be by conduction. Reradiation only occurs in the surface layer (water or land).

2.2. Transport of Heat towards the Poles

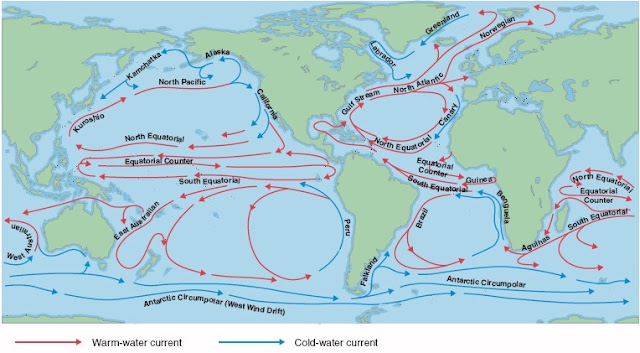

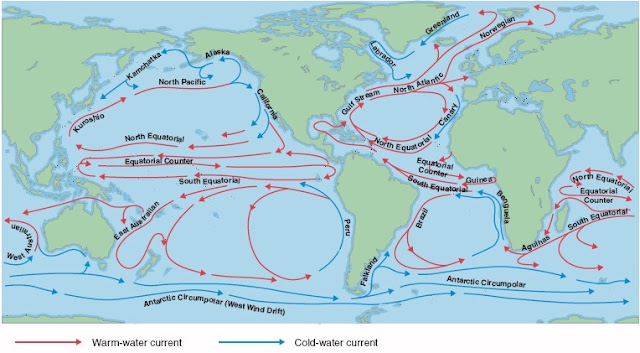

Dry air has a low heat capacity, but air can carry moisture in the form of water vapor, water droplets, or snow. Where water droplets are involved, the quantity of water carried can be enormous in Monsoons and Hurricanes. Accordingly, warm ocean currents and Hurricanes are the main carriers of heat from the Tropics towards the polar regions [8]. There can also be “rivers of water” carried to land areas by Monsoons in subtropical areas. The warm ocean currents carry large quantities of heat towards the Poles but are constrained by the distribution of land and water (Figure 1).

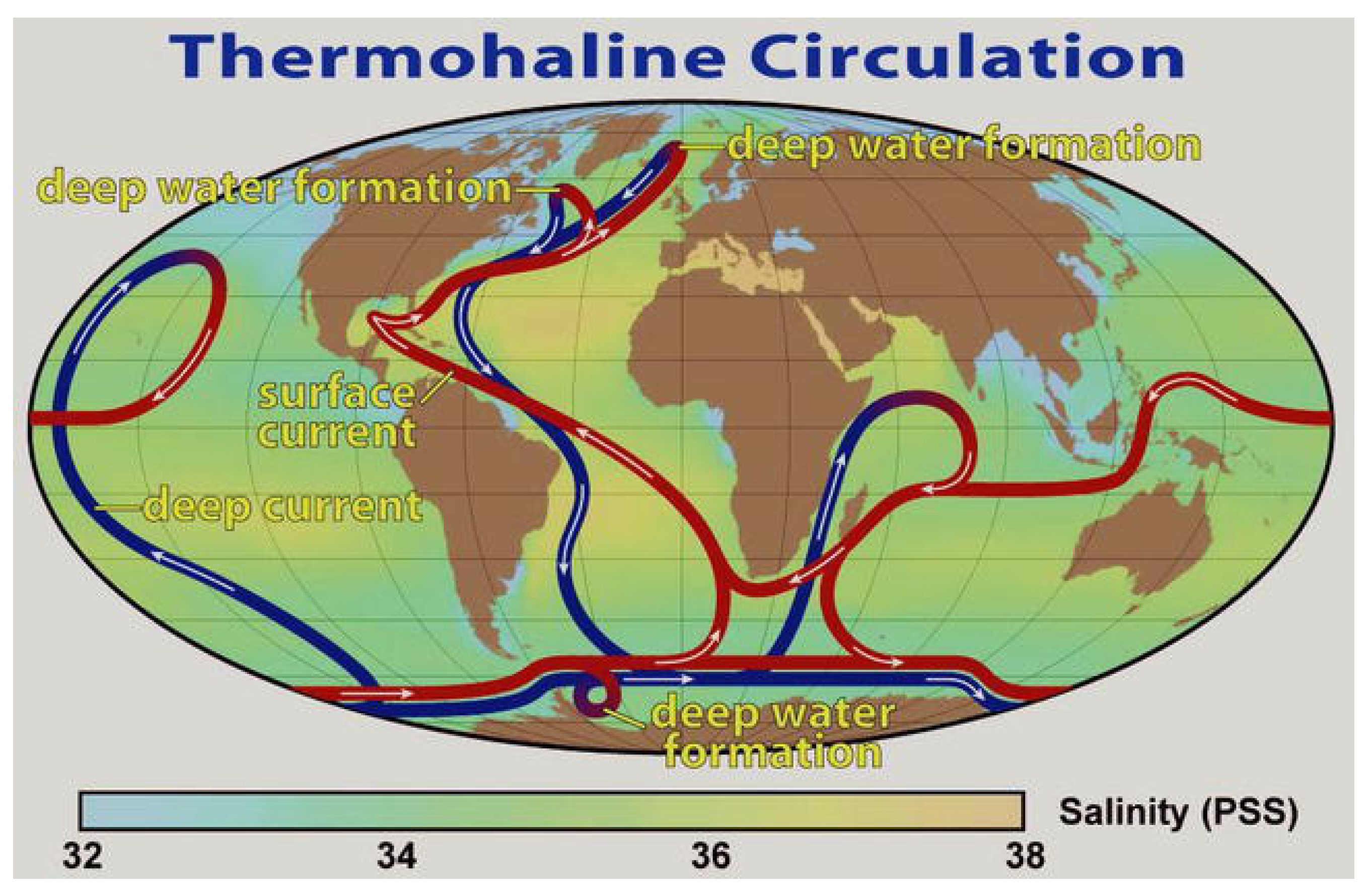

Figure 1. Distribution of cold and warm currents around the world [11]. Note that the warm currents are prevented from warming Antarctica by the cold Antarctic Circumpolar current, whereas the warm Gulf Stream penetrates northward into the North Atlantic Subarctic waters.

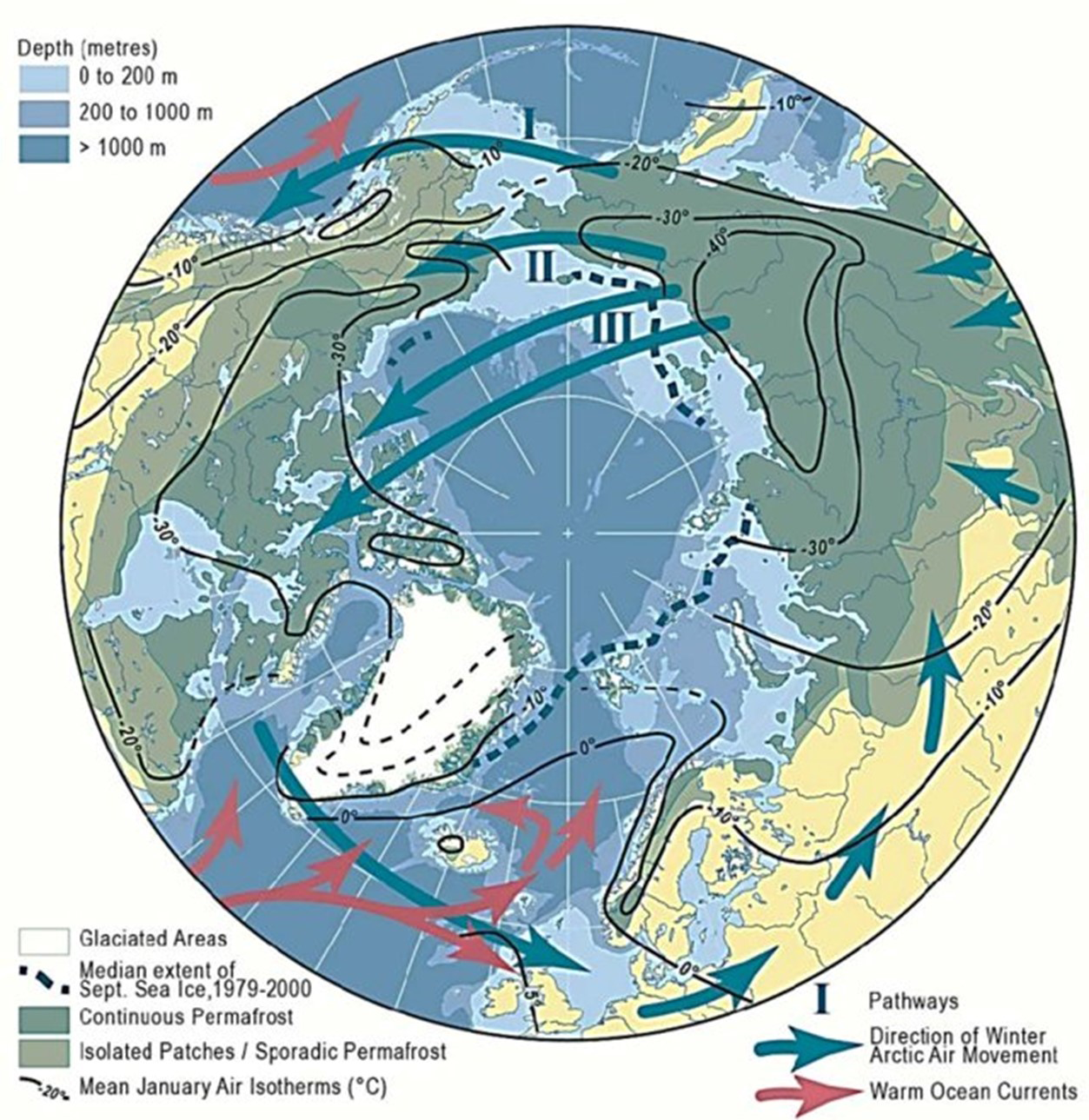

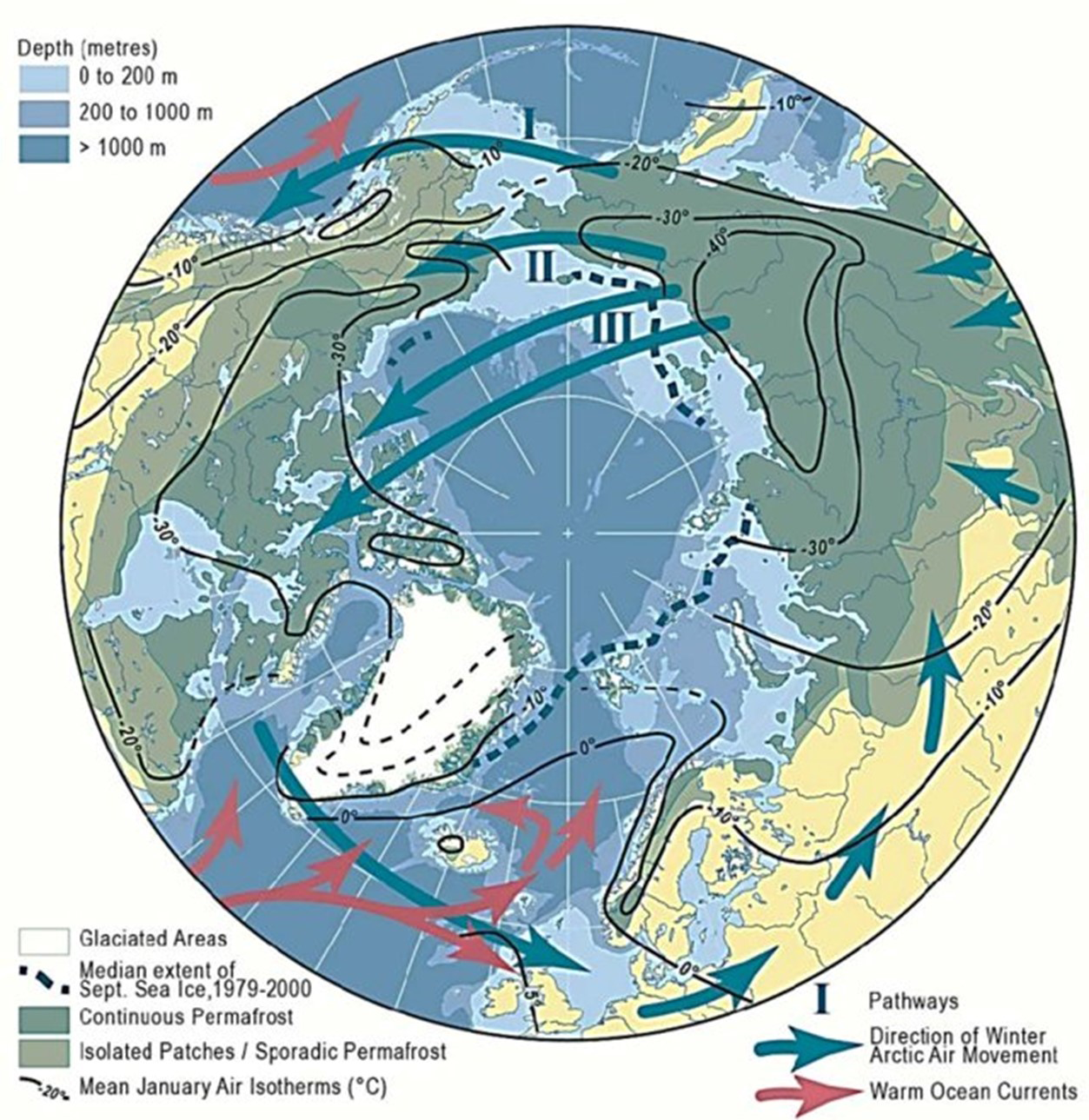

The primary source of old, dense Arctic Air is in the interior valleys of the mountains in Northern Siberia, where the coldest air temperatures commonly exceed −65 °C in winter [12]. They are partly fed by cold air drainage from Tibet flowing down its northern slope to the Hexi Corridor, and similar cold temperatures have been recorded from Fort Nelson, British Columbia [14], and from the high mountains in Utah. The cold Siberian air moves eastward along three main paths (Figure 2) and results in several different patterns of ice caps during the Wisconsin glaciation in North America. Path I is mainly used during the initial growth of the ice sheets and for changing Arctic air to Subtropical air, bringing about deglaciation of the western ice sheets during the retreat of the ice from its maximum glacial extent and the beginning of the subsequent Interglacial event.

Figure 2. Map showing the distribution of permafrost in the Arctic together with the mean surface air January isotherms (°C) and the adjacent warm and cold currents [13]. Note the three main paths (I to III) taken by the Arctic air as it moves from Siberia to northern Canada and the positions of the main warm ocean currents bringing heat from the Tropics.

Over oceans, this is primarily centered in the zone of Intertropical Convergence between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, where the sun is overhead for part of the year [10] (Figure 1). These are the main sources of the warm ocean currents that transfer heat northward in the northern hemisphere from the main hot centers of the oceans. Overheating of the tropical waters also results in onshore Monsoon events and “rivers of rain” coming northeastward from the Indian Ocean and the Central Pacific Ocean that bring large quantities of moisture to Subtropical areas such as India and southwestern North America.

For large areas of land, warm air masses originate where large dry deserts exist, such as the Sahara Desert in Africa, the Mohave Desert in Arizona, North America, or the Interior of Australia. The effects of these expand and contract as the sun changes position during the year and can bring drought conditions to southeast Africa and southern Europe.

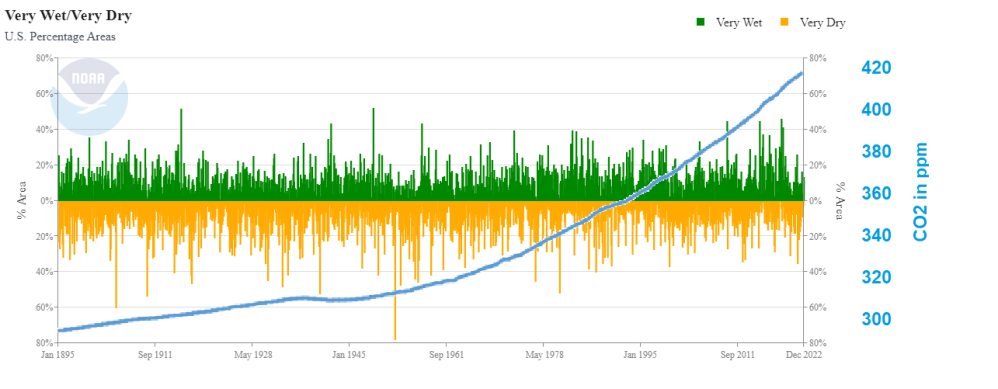

2.5. Effects of Humans on Climate Change

The IPCC argues that carbon dioxide coming from industrial plants controls the air temperature [16,17] (see Section 3.5). Certainly, deforestation, logging, agriculture, and urbanization have altered the albedo on land, but these changes do not produce sufficiently large temperature changes to be significant when compared with the quantity of solar radiation reaching the surface of the Earth. They may, however, cause substantial changes in precipitation, as in the case of Costa Rica, where deforestation of 85% of the rain forest resulted in a reduction in precipitation of c.30%. There is a marked difference between the warming of cities by the heat island effect and the rural areas of the northern hemisphere, which have not shown marked warming during the last 10 years [18,19,20,21].

3.2. Identification of Cold Events in the Oceans

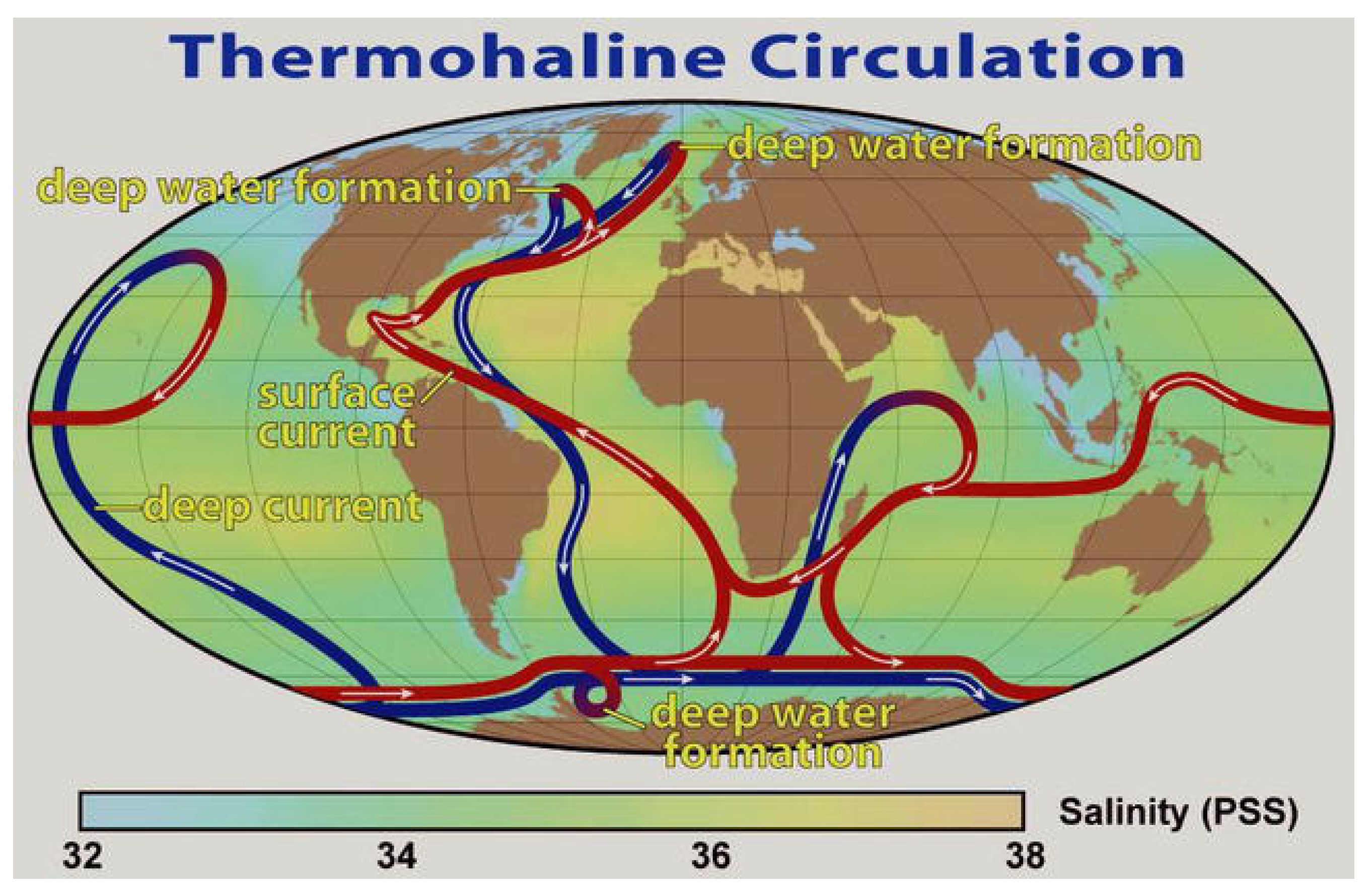

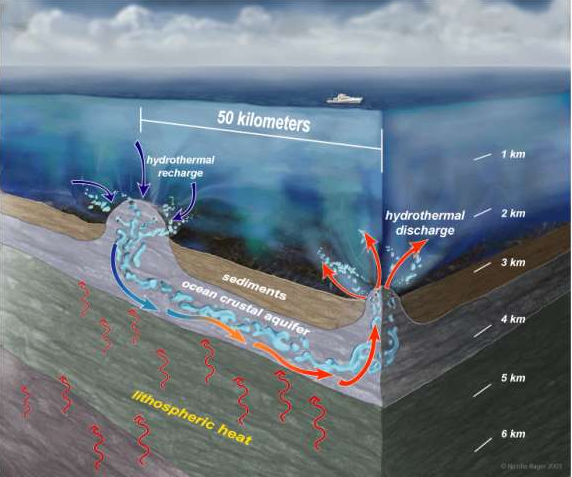

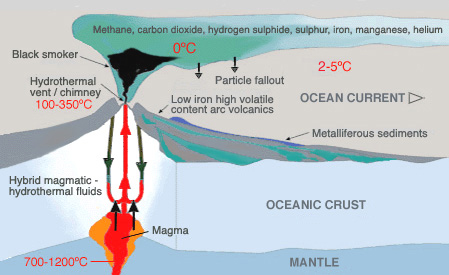

Some of the most important evidence for climatic changes has been found by Oceanographers. These include fluctuations in sea temperatures in the deep-sea cores and evidence for the transport of solar heat from the equatorial areas by warm currents in the seas and by hurricanes, as well as by deep thermohaline currents.

3.3. Fluctuations in Sea Temperatures Measured by δ O18 in Foraminifera

Shackleton was the first to report numerous alternating warm and cool assemblages of layers from deep sea cores in the Atlantic Ocean. Subsequent work showed that there were over 100 such fluctuations in the last 3.3 Ma B.P., and these became more marked in the upper layers of the cores, while the amplitude of temperature fluctuations increased towards the sediment surface (Figure 3) [28,29,30,31,32]. They showed a progressive cooling of the North Atlantic Ocean beginning about 3.5 Ma B.P. [27]. However, the frequency of the cold peaks is much greater than the 41 ka calculated by Milankovitch and appears to be controlled by his 23 ka precession cycle. The 41 ka cycle must be part of the cause of the variation in degree of cold from one cold period to the next.

Figure 4. Paths of the thermohaline deep water circulation of warm North Atlantic bottom water (red) and the cold Subarctic return flow (blue) around the oceans [13].

Inevitably, this buildup of heat in the North Atlantic creates a situation that results in periodic drastic events in the oceans. Oceanographers discovered a deep-water thermohaline circulation system over 50 years ago [30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], although they did not speculate on the source of the heat. They have carried out enough research to demonstrate that there is a cycle of climate change that has been occurring every 100 ka during the last 800 ka B.P. It consists of fast-moving, deep thermohaline currents (THC) that move heat down to the southern hemisphere and form part of a global thermohaline system [40]. A return flow of cold Antarctic surface water moves north to the North Atlantic Ocean to replace it and restore the former sea level [40]. This has been suggested to cause a rapid cooling of the northern hemisphere, with glacial advances commencing within about 12 years in Greenland [40]. It was called the “bipolar see-saw” by Broecker [41,42,43]. After this, a period of increasing expansion of cold glacial conditions takes place for about 85 ka, with the sea level falling as more water is stored as ice on land. The cold periods are punctuated by minor warming episodes about every 23 ka. It finally ends when the Arctic air mass reaches an extent such that the warming caused by the change in tilt of the axis of the Earth (precession) causes the Arctic air mass to retreat with its main flow changing from Paths II and III to Path I (Figure 1), i.e., from the northern paths to that centered on southern British Columbia (Figure 1). This produced deglaciation and an Interglacial warm period lasting 10–15 ka. The Milankovitch cycles, specifically the eccentricity and the precession cycles, are believed to control the system [5,6].

3.5. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Proposal

The IPCC is sponsored by the United Nations Organization and consists of selected climate scientists from several different countries. Their proposal in 1988 [17] is that human activities have resulted in increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, causing an increase in global temperature that overrides all other causes. It is assumed that the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide since the beginning of the industrial revolution is the cause of the warming [17]. This is not consistent with studies involving changes in temperature in rural areas of the northern hemisphere [18,19] or in much of the southern hemisphere. It is true that it is a greenhouse gas, but it only affects a small range of long-wave reradiation from the surface of the Earth. The latter has a much wider range of wavelengths in its reradiation that depend on the temperature of the radiating surface. The increase in this gas is measured primarily at a single station at the summit of Mount Mauna Loa on the island of Hawaii, and the increase parallels the change in air temperature at that station since about 1900 A.D. It is generally assumed that it does not vary significantly around the globe except for minor seasonal changes.

No consideration is given to the fact that as the water in the oceans warms, the carbon dioxide dissolved in it decreases in solubility, and degassing takes place. This degassing from the oceans is slow and matches the increase in temperature of the upper 2000 m of the North Atlantic Ocean, at any rate for the data for that location since 1910. The warming appeared to precede increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation at 24 sites around the world during the last deglaciation [43], but this was the result of comparing surface water temperature with the total carbon dioxide degassed from the entire water column at each site. The relationship of carbon dioxide to atmospheric air temperature has been widely discussed [44], and it has been shown that temperature changes precede changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide in the case of Antarctic cores [45,46].

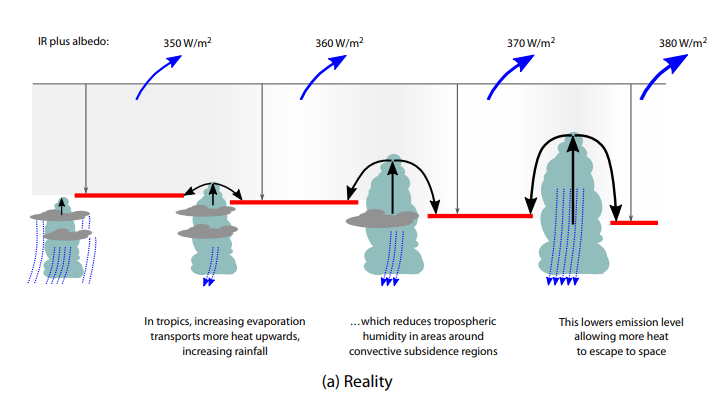

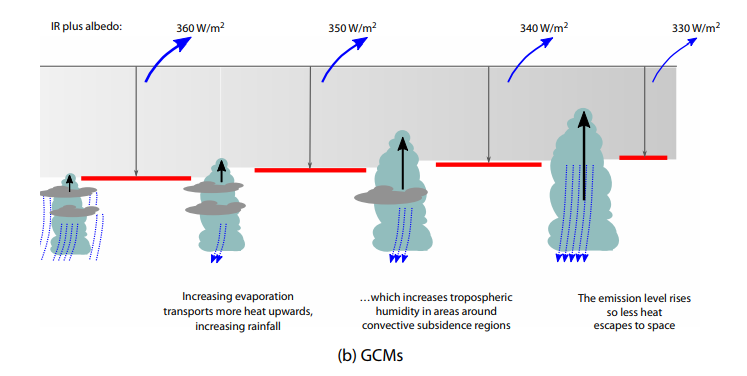

Payet and Holmes provide summaries of some of the main arguments questioning the validity of the IPCC theory [47,48], while Christy has testified before the U.S. Congress that the mathematical models used by the IPCC do not match the real-world observations [49]. The theory has been embraced by governments, research workers who saw it as a means of obtaining research grants, commercial firms who saw the possibilities of new work, environmentalists, and the press since it was a simple explanation that could easily be understood by the public, but it has been severely criticized by a substantial number of experienced scientists. For example, there have been over 75,000 comments published on ResearchGate concerning the relationship between seawater temperature and increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide. Many are not very chivalrous!

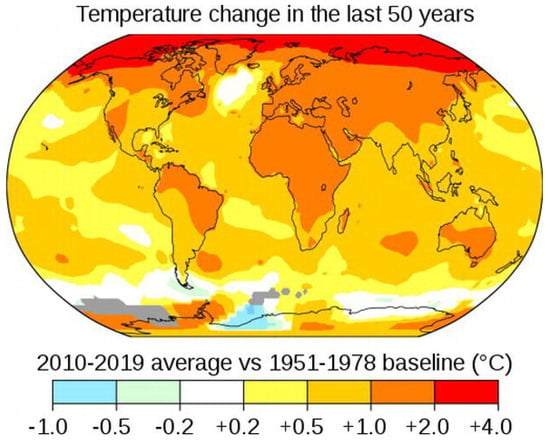

An obvious problem is found when examining the map of the distribution of climate change (mean yearly air temperature) obtained by NASA from satellites (Figure 5). The main areas of warming are in Northern Canada and the Arctic, with lesser warming in the Sahara and the Australian Outback! Eastern China and Germany show no obvious warming. Obviously, this does not fit in with the main industrial centers in the world!

Since atmospheric carbon dioxide is present in extremely low quantities and has a narrow band of wavelengths that it absorbs, it cannot possibly compete in effect with the much larger total solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. It is a colorless, odorless gas with a molecular weight of 44 and is therefore mainly held down in the lower part of the atmosphere by gravity. Thus, models that assume that carbon dioxide rises to the outer portion of the atmosphere are unrealistic. Water, in all its phases, is a much more potent agent for moving heat around the globe.

Figure 5. Map showing the measured mean annual temperature change around the world between 1951–1978 and 2010–2019 (NASA). The warming trend is not global and varies from being negative along the coast of Antarctica to over 4 °C around the Arctic basin.

The evidence for greater solubility of carbon dioxide in water at colder temperatures implies carbon dioxide moving from the air into the oceans during cold events [33] and can result in large quantities of the gas reacting with calcium ions to produce large amounts of calcium carbonate in the form of a calcareous, fine-grained limestone, e.g., during the Devonian and Carboniferous Periods. This implies that its abundance in the atmosphere is not entirely dependent on temperature. Both methane and carbon dioxide are chemicals that can and do take part in chemical reactions, whereas temperature is a measure of heat energy and cannot be created or destroyed. However, it can be changed into other forms of energy.

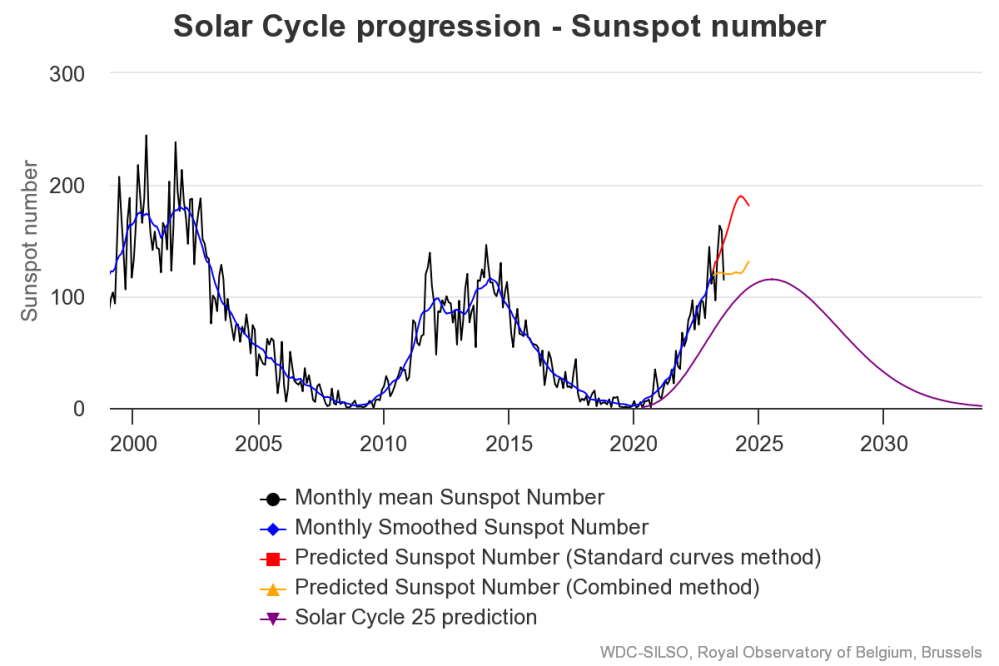

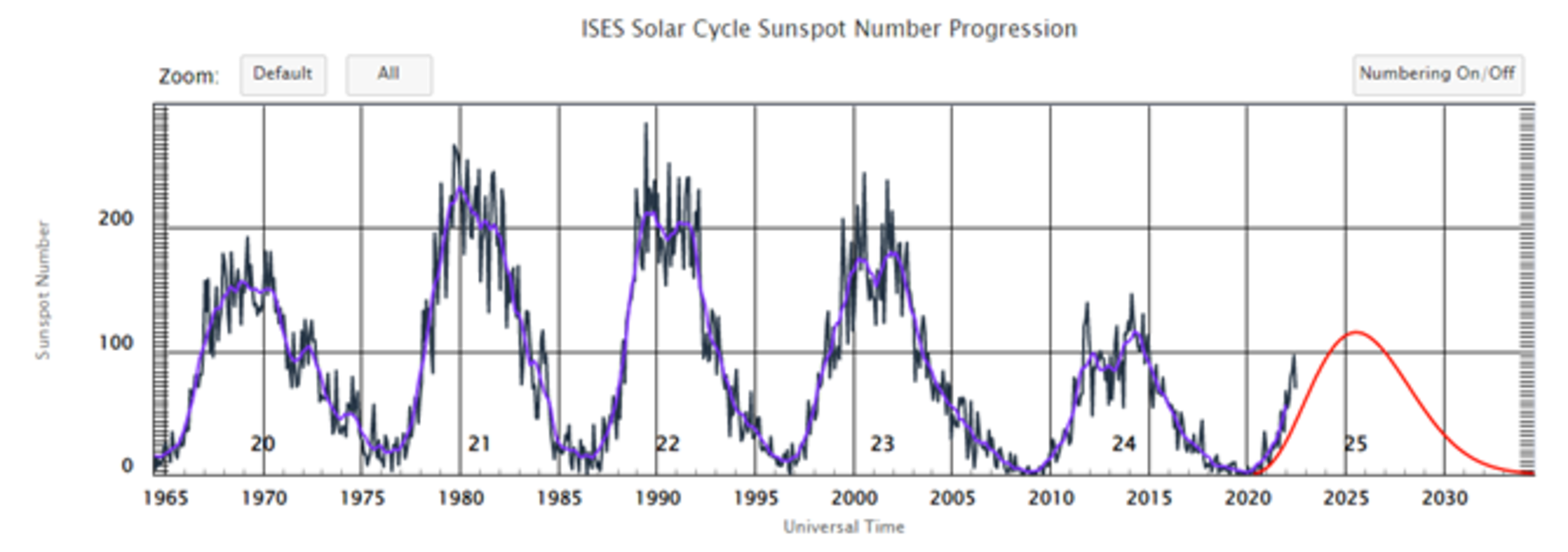

3.5.1. Ongoing Measurements of the Solar Energy Reaching the Surface of the Atmosphere

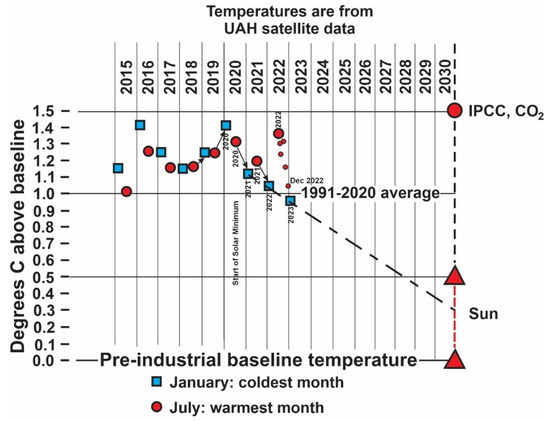

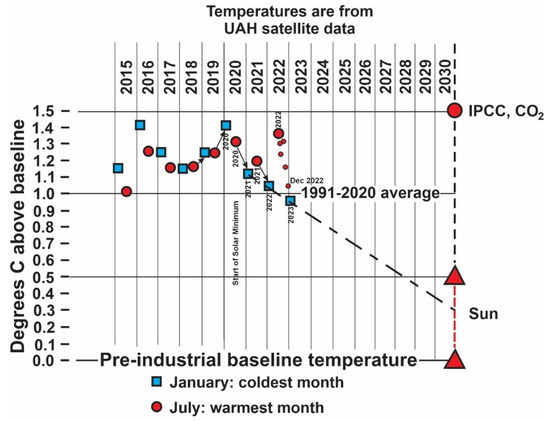

The basic difference between the IPCC proposal and the other ideas is the source of the additional heat being received in certain areas of the world. The obvious test is to measure the solar heat reaching the upper surface of the Earth’s atmosphere. In 2015, the U.S. Government started collecting satellite measurements of the incoming radiation at the surface of the atmosphere over Salt Lake City, Utah (Figure 2), latitude 40° 26′ 20″ north, longitude 109° 57′ 30″ west from Greenwich.

Figure 6 shows the results obtained by the end of winter 2023, updated from Pangburn [50]. Shown in blue are the minimum winter temperatures compared with the preindustrial baseline, which are consistent with the precession cycle of Milankovitch commencing its decreasing mode of solar energy in the higher latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere in 2020. Thereafter, the winter temperatures at these sites decrease, indicating the commencement of a cooling trend that is likely to continue for the next 11.5 ka, based on the Milankovitch cycles. A corresponding warming trend should be occurring in the higher latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere. The current world record for cold is −98 °C, recorded in the Antarctic winter of 2018 [15], which is likely to stand for a long time since the change in the precession cycle should produce warmer winters there in the near future. In contrast, the winters in Western Canada and the southwest United States will be longer, colder, and have increasing precipitation.

Figure 6. Comparison of incoming solar radiation for specific summer and winter months measured by satellites in the atmosphere over Utah from 2015 to 2023, showing the difference between actual totals by season and predicted IPCC CO2 levels (modified from [52]).

Conclusions

Enough theories have been tried and tested so that we now have a much better idea of how the climatic cycle works. The cycle commenced as soon as the Earth cooled down and is closely related to the main source of heating coming from the Sun and the Milankovitch cycles [5,6]. The Sun has been steadily warming since the beginning of the Earth’s history [31]. If the Astronomers are correct, this heating will continue until the Sun becomes a Red Star and swallows up the inner four planets one by one, possibly starting about 5 Ma in the future. This increase is superimposed on the 23 ka, 41 ka, and 100 ka cycles resulting from the relative positions and movements of the Sun and the Earth.

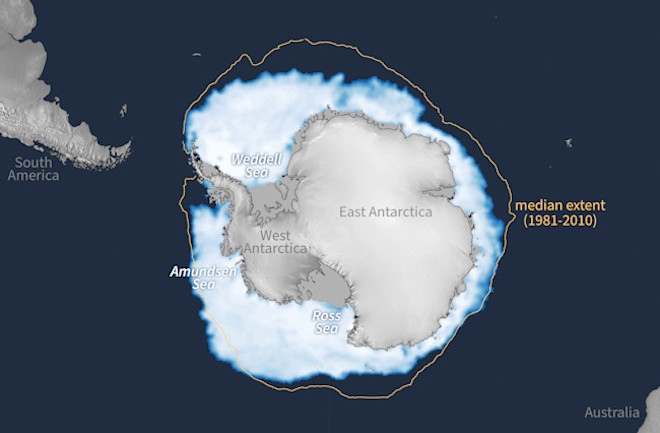

The climate of the Earth is driven by the uneven solar heating of the surface of the Earth and the movements of the excess heat in the tropics towards the cooler polar regions, primarily by the movements of ocean currents, modified by the movements of air masses. The rotation of the Earth results in the Coriolis force causing fluids to rotate in a clockwise direction in the northern Hemisphere and in an anticlockwise direction in the southern Hemisphere. It also results in an eastward movement of the air masses around the Poles of the Earth (Figure 1). Oceans make up 70% of the surface of the Earth, and the thermal properties of water result in ocean currents being the primary method of transporting heat towards the poles, aided by hurricanes. The circular shape of Antarctica prevents the direct transport of heat to Antarctica, in contrast to the heating of adjacent land areas of the Northern Hemisphere via the North Atlantic Ocean. The excess heat in the North Atlantic Ocean causes intense evaporation of sea water, producing dense, deep-water thermohaline masses that periodically move south to the colder water circulating around Antarctica, thus causing a periodic return flow of cold Antarctic surface water to the North Atlantic.

Carbon dioxide is a gas that is of fundamental importance to life as we know it. If its concentration in the atmosphere becomes too low, the bulk of the living things on the surface of the Earth will die, and the surface will become as barren as the other planets in the solar system [31,43]. There seems to be no connection between carbon dioxide and the temperature of the Earth [14,19,28,29,43,44,45,46].

Accordingly, the policies used by policymakers need to be changed to

eliminate the burial of carbon dioxide underground,

not provide large sums of public money to foreign firms to build battery factories,

and realize that we will still need the oil and gas industry in the future.

The gas tax should be eliminated.

Stuart Arthur Harris is Professor Emeritus, Department of Geography, University of Calgary

Footnote

This detailed consolidation of contemporary climate science is new and welcome. Of course it brings in previous perspectives ignored or dismissed by IPCC, an important example being work of Oceanographers expressed in many posts here under the category Oceans Make Climate. An early and succinct expression of this paradigm was provided by E M. Smith (Chiefio):

“The Earth, a rocky sphere at a distance from the Sun of ~149.6 million kilometers, where the Solar irradiance comes in at 1361.7 W/m2, with a mean global albedo, mostly from clouds, of 0.3 and with an atmosphere surrounding it containing a gaseous mass held in place by the planet’s gravity, producing a surface pressure of ~1013 mb, with an ocean of H2O covering 71% of its surface and with a rotation time around its own axis of ~24h, boasts an average global surface temperature of +15°C (288K).

Why this specific temperature? Because, with an atmosphere weighing down upon us with the particular pressure that ours exerts, this is the temperature level the surface has to reach and stay at for the global convectional engine to be able to pull enough heat away fast enough from it to be able to balance the particular averaged out energy input from the Sun that we experience.

It’s that simple.” E. M. Smith

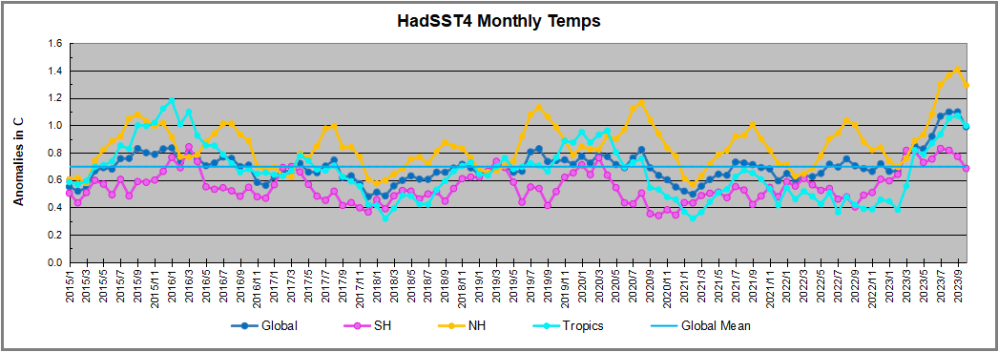

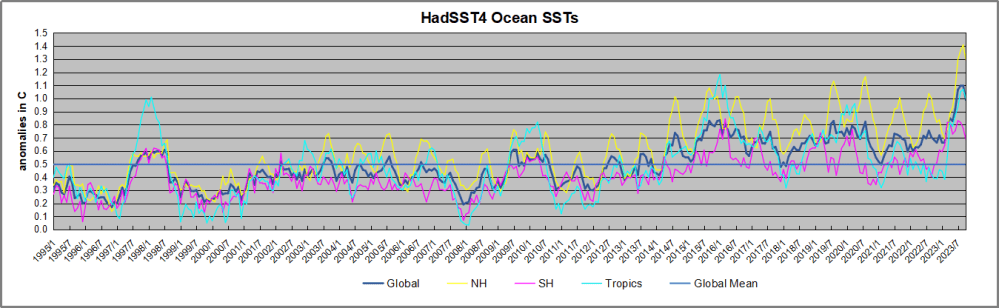

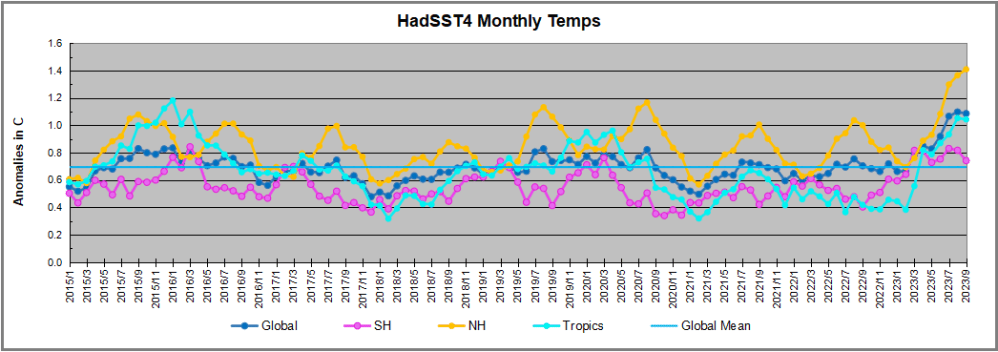

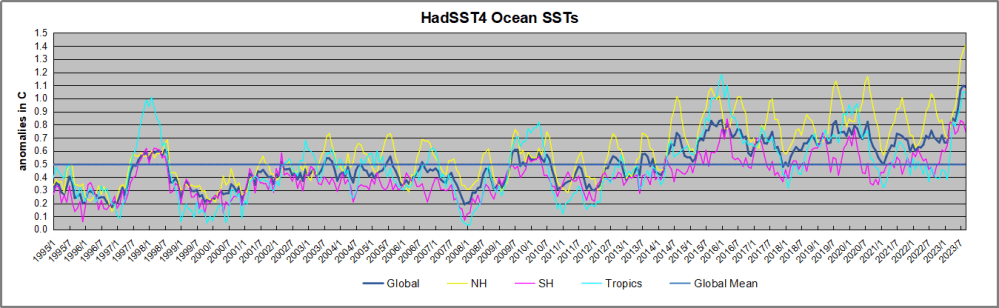

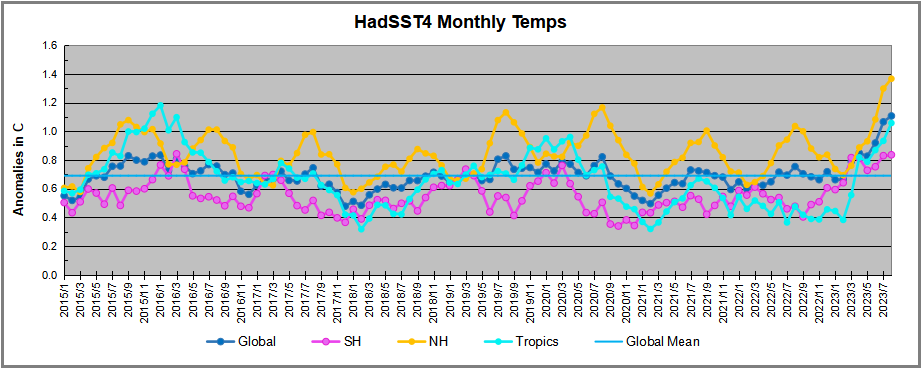

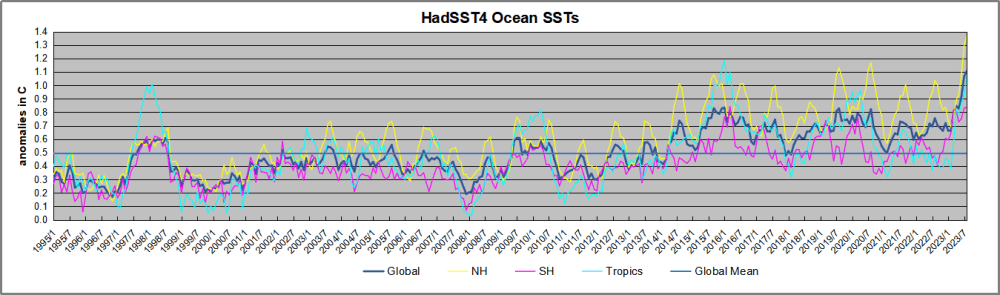

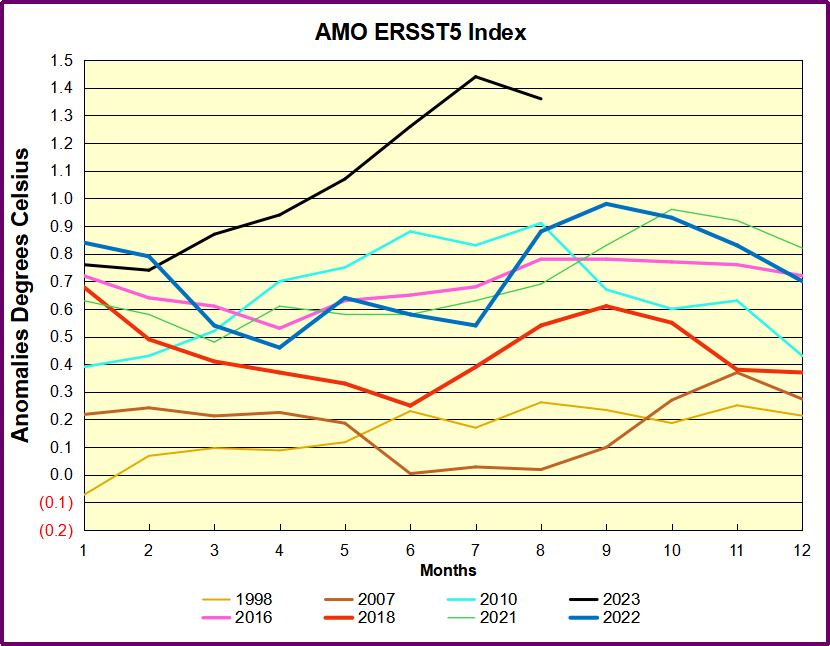

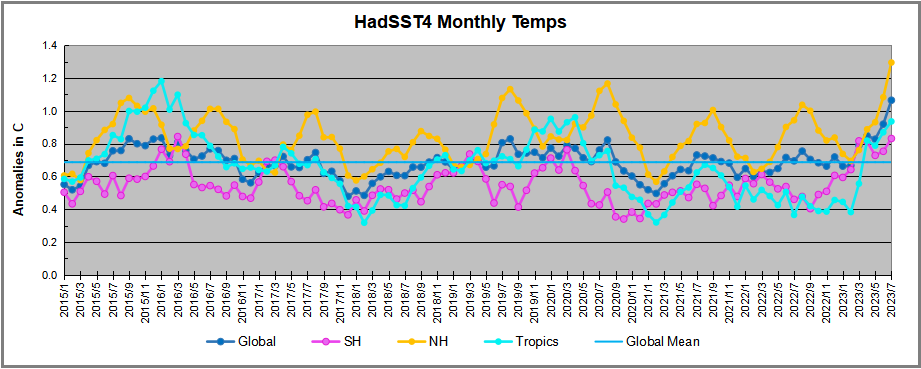

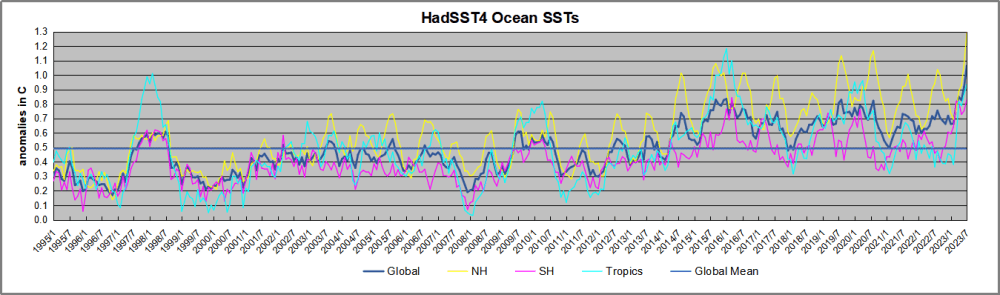

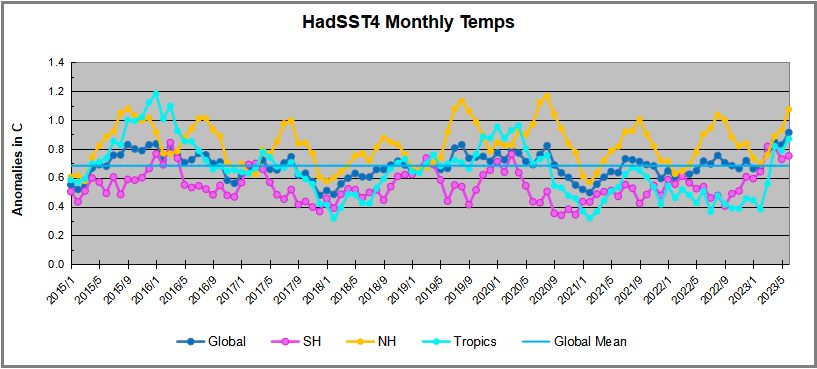

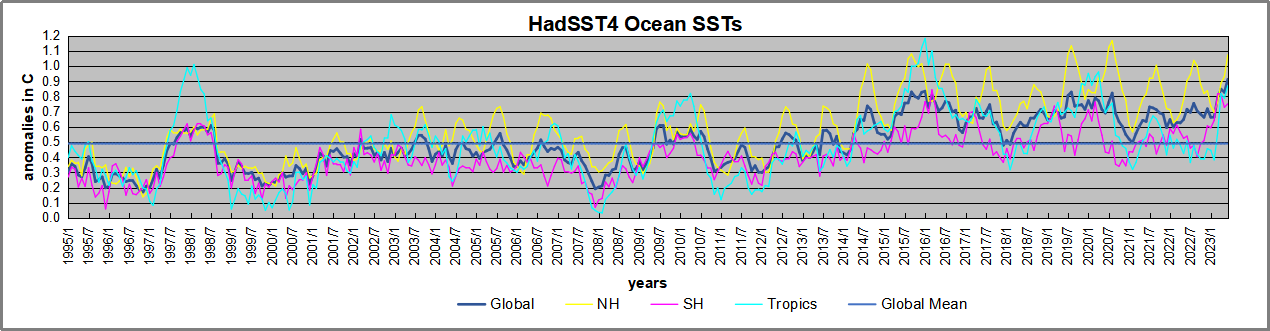

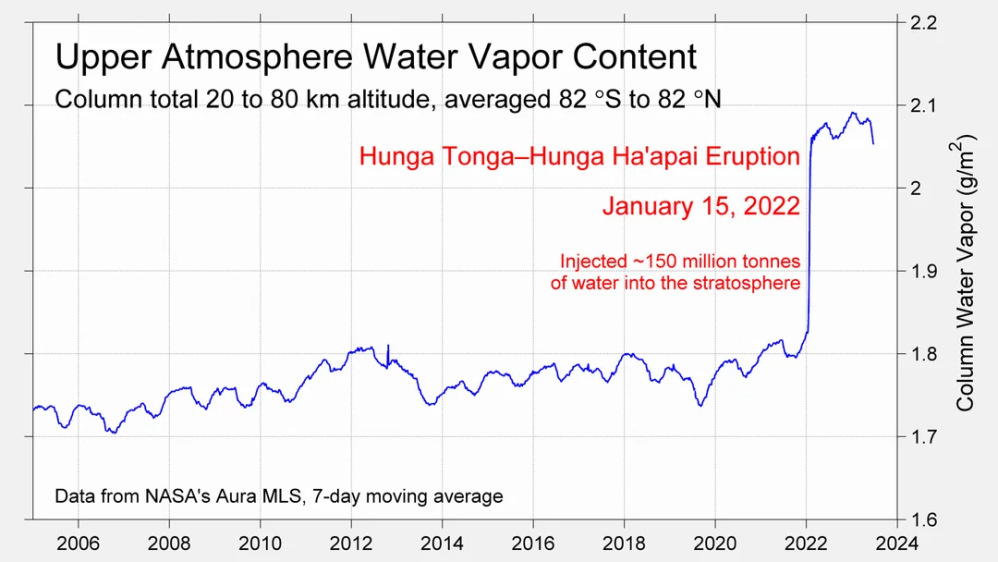

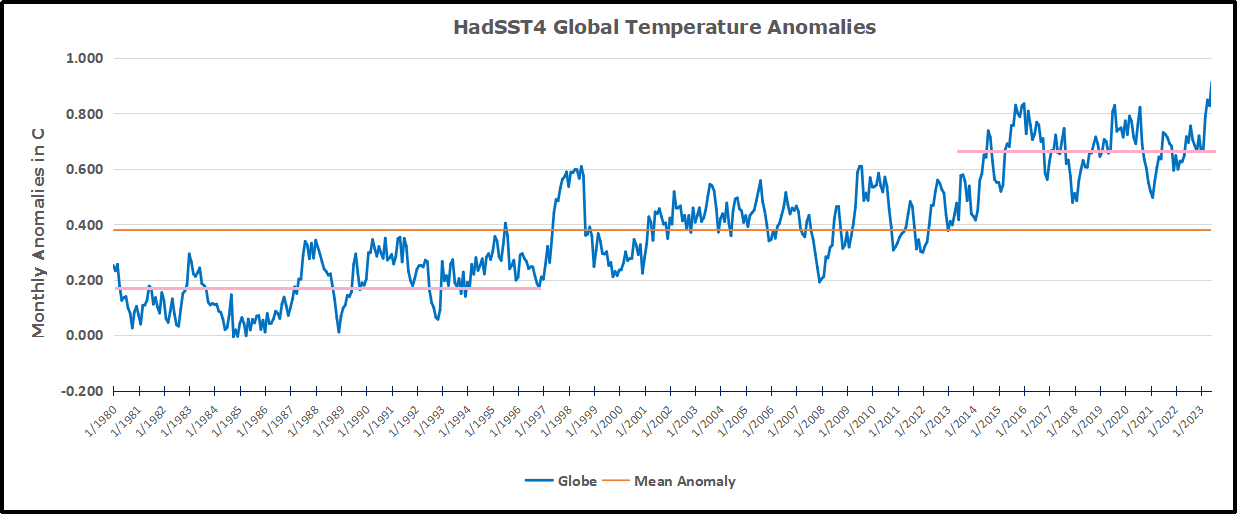

The purple line is the average anomaly 1980-1996 inclusive, value 0.18. The orange line the average 1980-202306, value 0.38, also for the period 1997-2012. The red line is 2013-202306, value 0.64. As noted above, these rising stages are driven by the combined warming in the Tropics and NH, including both Pacific and Atlantic basins.

The purple line is the average anomaly 1980-1996 inclusive, value 0.18. The orange line the average 1980-202306, value 0.38, also for the period 1997-2012. The red line is 2013-202306, value 0.64. As noted above, these rising stages are driven by the combined warming in the Tropics and NH, including both Pacific and Atlantic basins.