About Canadian Warming: Just the Facts

Just in time for the Trudeau carbon tax taking effect, we have all the media trumpeting “Canada Warming Twice as Fast as Global Rate–Effectively Irreversible.” That was written by some urban-dwelling climate illiterates who are woefully misinformed. Let’s help them out with some facts surprising to people who don’t get out much. Unfortunately ignored this week was an informative CBC publication that could have spared us “fake news” spewing across the land, from Bonavista to Vancouuver Island, as the song says.

Surprising Facts About Canada are presented in a CBC series 10 Strange Facts About Canada’s Climate Excerpts below provide highlights in italics with my bolds.

Through blistering cold winters to hot muggy summers; torrential rain, blinding snowstorms, deadly tornados and scorching drought, Canadians experience some of the planet’s most diverse weather systems. [ Uh oh, averaging all of that could be a problem]

Canada is as tall as it is wide, creating a wide range of climate conditions.

Canada has the largest latitude range of any country on the planet. Our southern border lies at the same latitude as northern California, while our northern edge reaches right to the top of the world. It’s rarely the same season in the same place at the same time. In early April, the Arctic may still be in the throes of a frigid winter, while the south can experience summer-like temperatures. No doubt, our weather forecasters are the busiest in the world!

Canada has an ‘iceberg alley’.

Pieces of glaciers from the coast of Greenland are picked up by the Labrador Current, a counter-clockwise vortex of waters in the North Atlantic Ocean. Those broken pieces become icebergs that float in the sea off northeast Newfoundland where Fogo Island lies. Navigating the area is risky for ships; in fact this is where the mighty Titanic sank in 1912. But it’s a boon to tourism. Iceberg seekers flock to the area to watch (safely) from the shore and boast about drinking 10,000-year-old fresh water taken from an iceberg floating in the ocean.

Niagra Falls (the Canadian side)

Canada is (really) cold.

It’s certainly not surprising to most Canadians that we are tied with Russia for the title of ‘coldest nation in the world.’ Over our vast country, we have an average daily temperature of -5.6C. This is deadly cold. More of us — about 108 — die from exposure to extreme cold than from any other natural event. And that’s not counting Canadian wildlife who are more susceptible to Canada’s icy climate than we are.

Calgary Golfer February 9, 2016.

Every winter, southern Alberta is the ‘Chinook’ capital.

For six months — from November to May — warm dry winds rush down the slope of the Rocky Mountains towards southern Alberta. Often moving at hurricane-force speeds of 120 km per hour, they can bring astonishing temperature changes and melt ice within a couple of hours. In 1962 Pincher Creek saw a record temperature rise of 41C, from -19 to 22 in just one hour. Chinook is also known as the ‘ice-eater’ among locals who appreciate the break from winter that the winds provide.

Newfoundland is the foggiest place in the world.

At the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, the cold water from the Labrador Current from the north meets the warmer Gulf Stream from the south. The result is a whopping 206 days of fog a year. In the summer, it’s foggy 84 per cent of the time! It’s also the richest fishery in the world, the fog is a serious hazard to ships in the region.

View of the Haughton-Mars Project Research Station (HMPRS) on Devon Island, Nunavut, Arctic Canada

Canada’s North is actually a desert

Canada’s North is very cold and dry with very little precipitation, ranging from 10-20 cm a year. Temperatures average below freezing most of the year. Together, they limit the diversity of plants and animals found in the North. And it’s huge: this polar desert covers one seventh of Canada’s total land mass.

In 1816, Canada didn’t have a summer.

If winter in Canada weren’t bad enough, in 1816 the country’s eastern population were sledding in June and thawing water cisterns in July. Trees shed their leaves and there were reports of migratory birds dropping dead in the streets.

Over in Europe, the weird weather stoked anti-American sentiment. People opposed to emigration said that North America was inhospitable and getting colder every year.

Representation of Mount Tambora 1815 eruption in Indonesia.

Ironically, as eastern Canada stayed cool, the Arctic warmed, creating flotillas of icebergs off the coasts of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. At the time, it was thought that the icebergs were the cause of the cooling, like a giant glass of iced lemonade. What was the real reason? In 1815, the Tambora volcano erupted in Indonesia, spewing tonnes of ash and dust into the air. Less sunlight reached the earth and this caused the planet’s surface to cool. The volcanic eruption changed the climate in different ways around the world, but Eastern Canadians were treated to the summer that just didn’t come.

The Prairies face brutal temperature extremes.

It’s no surprise that Regina, Saskatchewan — which lies smack in the middle of Canada’s prairies — lays claim to both the country’s lowest recorded temperature, -50C on January 1, 1885 and the highest, 43.3C on July 5, 1937. Without the moderating effects of a large body of water, Canada’s Prairies are vulnerable to some of the worst weather Canada has to offer.

Hopewell Rocks at the Bay of fundy. Photo: gregstokinger

The Bay of Fundy has the largest tides in the world.

Twice each day, 160 billion tonnes of seawater flow in and out of this small area in Nova Scotia — more than the combined flow of the world’s freshwater rivers. The tides reach a peak of 16 metres (as high as a five-storey building) and take about six hours to come in. The most extreme tides in the Bay occur twice each month when the earth, moon and sun are in alignment and together they create a larger-than-usual gravitational pull on the ocean, creating a “spring tide” (not to be confused with the season spring).

Lightning over Lake St. Clair Photo: seebest

Windsor is the thunderstorm capital of Canada.

Hot, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico funnels up through Windsor and the Western Basin of Lake Erie creating the perfect conditions for thunderstorms. About 251 lightning flashes per 100 square kilometres happen every year when small pieces of frozen raindrops collide within thunderclouds. The clouds fill with electrical charges that are eventually funnelled to the ground as lightning.

Summary

With all that going on, all the variety of temperature, precipitation, weather events and seasonalities, no one noticed it had warmed much, and would be grateful if it had. With all the alarms sounding about the Arctic meltdown in the last decades, let’s consider the best long-service stations in the far north.

According to the “leaked report”, Canada’s annual average temperature over land has warmed 1.7 C when looking at the data since 1948. But that claim is misleading when recent data is considered.

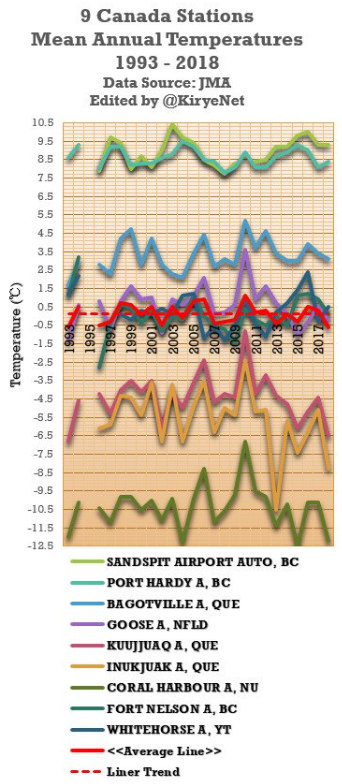

Over the past 25 years, since scientists began to warn that the planet was warming in earnest, there has not been any warming when one looks at the untampered data provided by the Japan meteorology Agency (JMA) that were measured by 9 different stations across Canada. These 9 stations have the data dating back to around 1983 or 1986, so I used their datasats.

Looking at the JMA database and plotting the stations with longer term recording, we have the following chart:

Though temperatures over Canada no doubt have risen over the past century, there has not been any real warming in over 25 years. Rather, there’s been slight cooling, though not statistically significant. Clearly there hasn’t been any Canadian warming recently.

So it is misleading — to say the least — to give the impression that Canada warming has been accelerating. Thanks to Kirye for posting this at No Tricks Zone

See also Cold Summer in Nunavut

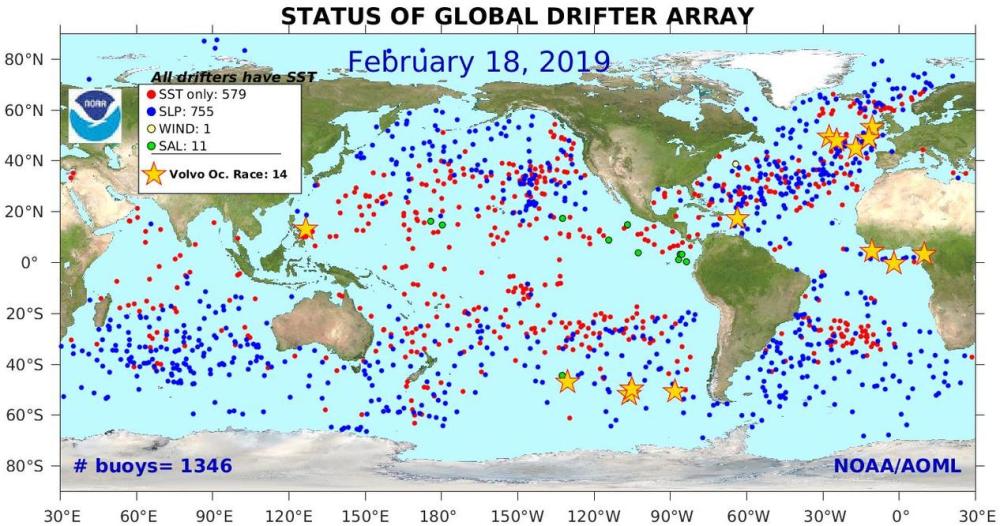

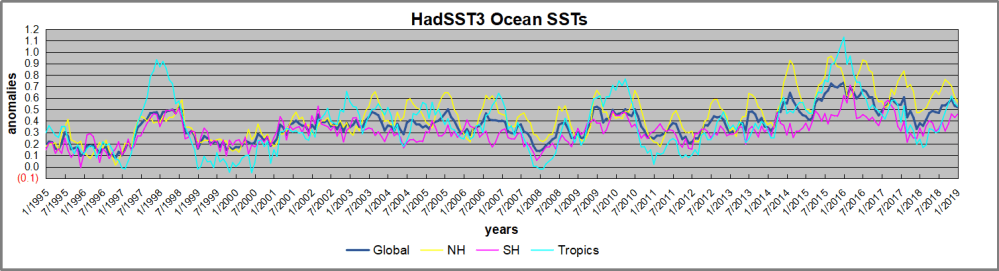

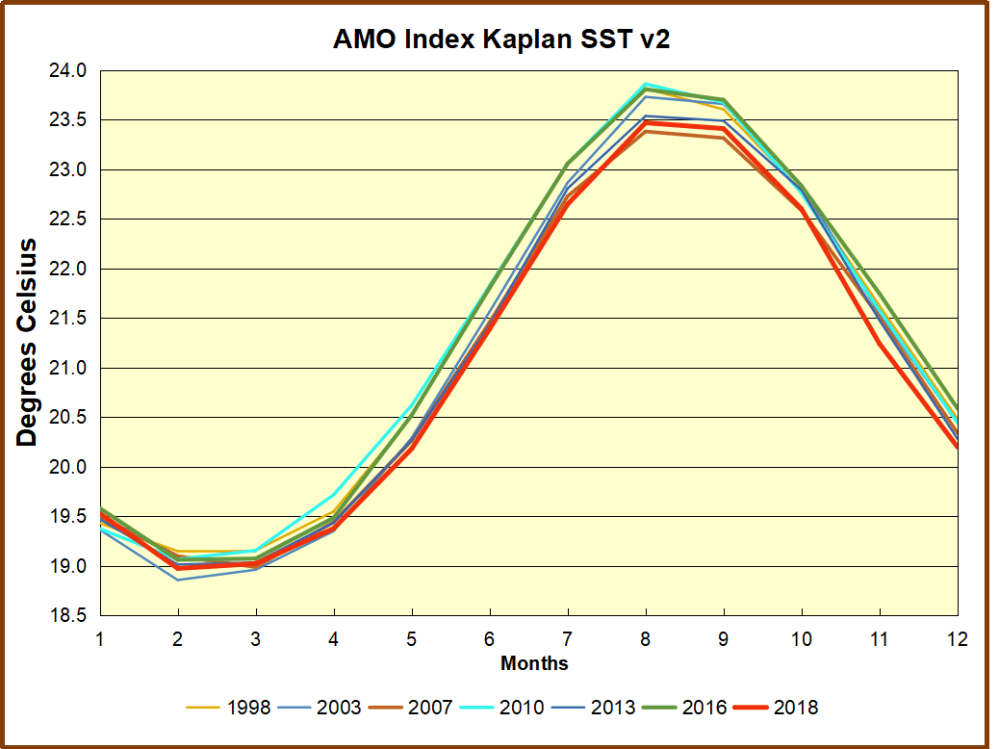

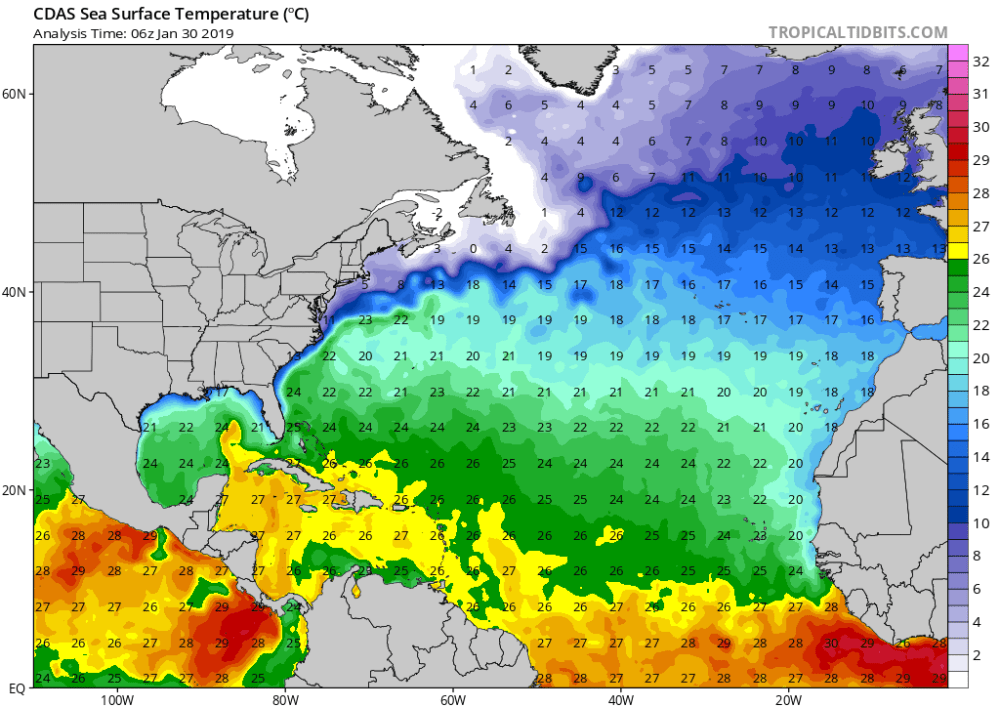

The best context for understanding decadal temperature changes comes from the world’s sea surface temperatures (SST), for several reasons:

The best context for understanding decadal temperature changes comes from the world’s sea surface temperatures (SST), for several reasons:

The best context for understanding decadal temperature changes comes from the world’s sea surface temperatures (SST), for several reasons:

The best context for understanding decadal temperature changes comes from the world’s sea surface temperatures (SST), for several reasons:

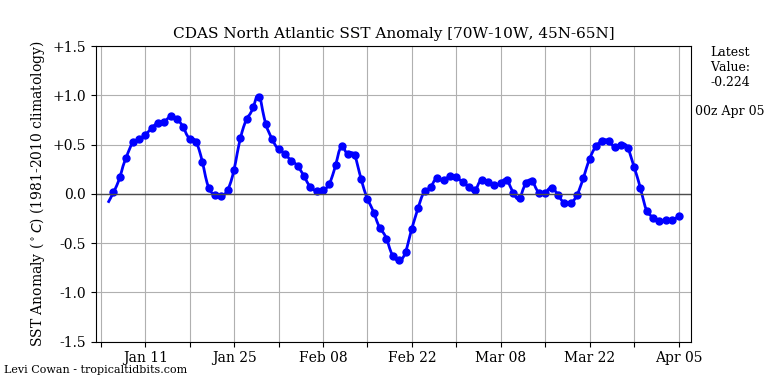

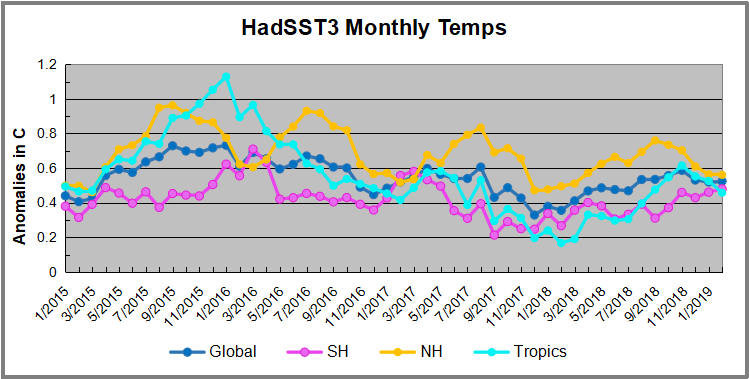

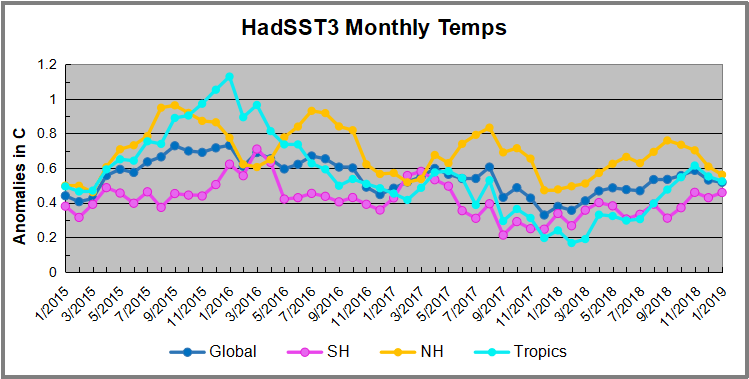

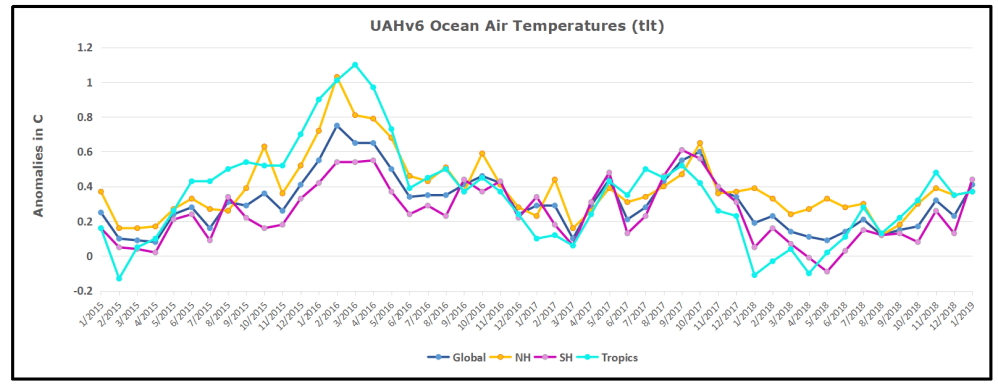

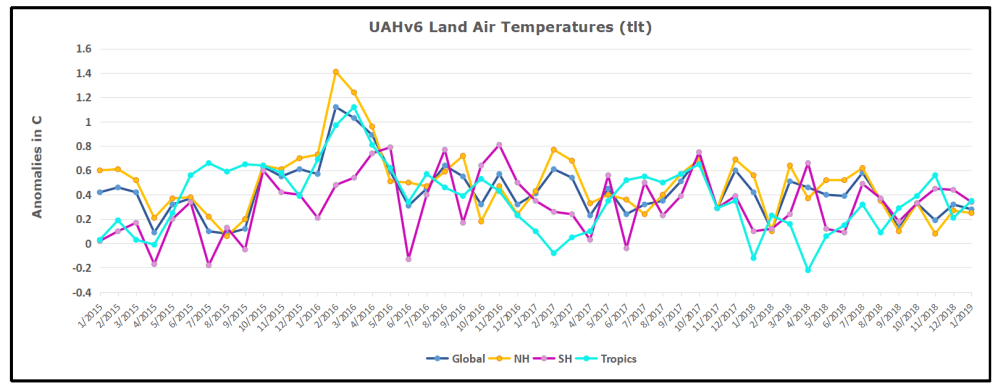

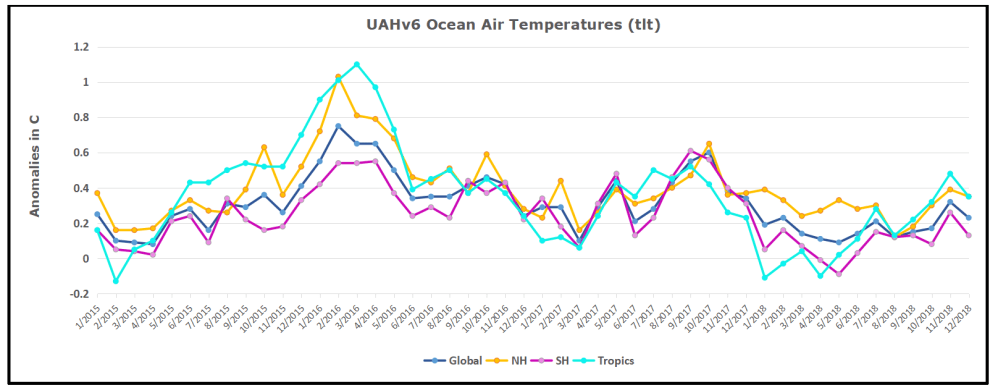

The anomalies over the entire ocean dropped to the same value, 0.12C in August (Tropics were 0.13C). Warming in previous months was erased, and September added very little warming back. In October and November NH and the Tropics rose, joined by SH. In December 2018 all regions cooled resulting in a global drop of nearly 0.1C. Now in January an upward jump in SH overcame slight cooling in NH and the Tropics, pulling up the Global anomaly as well. While the trajectory is not yet set, it is the highest ocean air January since 2016.

The anomalies over the entire ocean dropped to the same value, 0.12C in August (Tropics were 0.13C). Warming in previous months was erased, and September added very little warming back. In October and November NH and the Tropics rose, joined by SH. In December 2018 all regions cooled resulting in a global drop of nearly 0.1C. Now in January an upward jump in SH overcame slight cooling in NH and the Tropics, pulling up the Global anomaly as well. While the trajectory is not yet set, it is the highest ocean air January since 2016.

The anomalies over the entire ocean dropped to the same value, 0.12C in August (Tropics were 0.13C). Warming in previous months was erased, and September added very little warming back. In October and November NH and the Tropics rose, joined by SH last month., In December 2018 all regions cooled resulting in a global drop of nearly 0.1C.

The anomalies over the entire ocean dropped to the same value, 0.12C in August (Tropics were 0.13C). Warming in previous months was erased, and September added very little warming back. In October and November NH and the Tropics rose, joined by SH last month., In December 2018 all regions cooled resulting in a global drop of nearly 0.1C.