There are two reasons why Bill Gates and hundreds of Corporations and many countries are backtracking on commitments to decarbonize. One is disbelieving the false advertising that the planet is in danger and can be saved by Net Zero efforts. Second is sobering up to the fact that decarbonizing the world is an impossible fantasy. This post includes content from Gary Abernathy on the first point and some quotes from Vaclav Smil’s recent paper on the second.

- Abernathy writes at Real Clear Energy In practice, ‘Net Zero’ Was Exactly How Much Such Pledges Were Worth. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

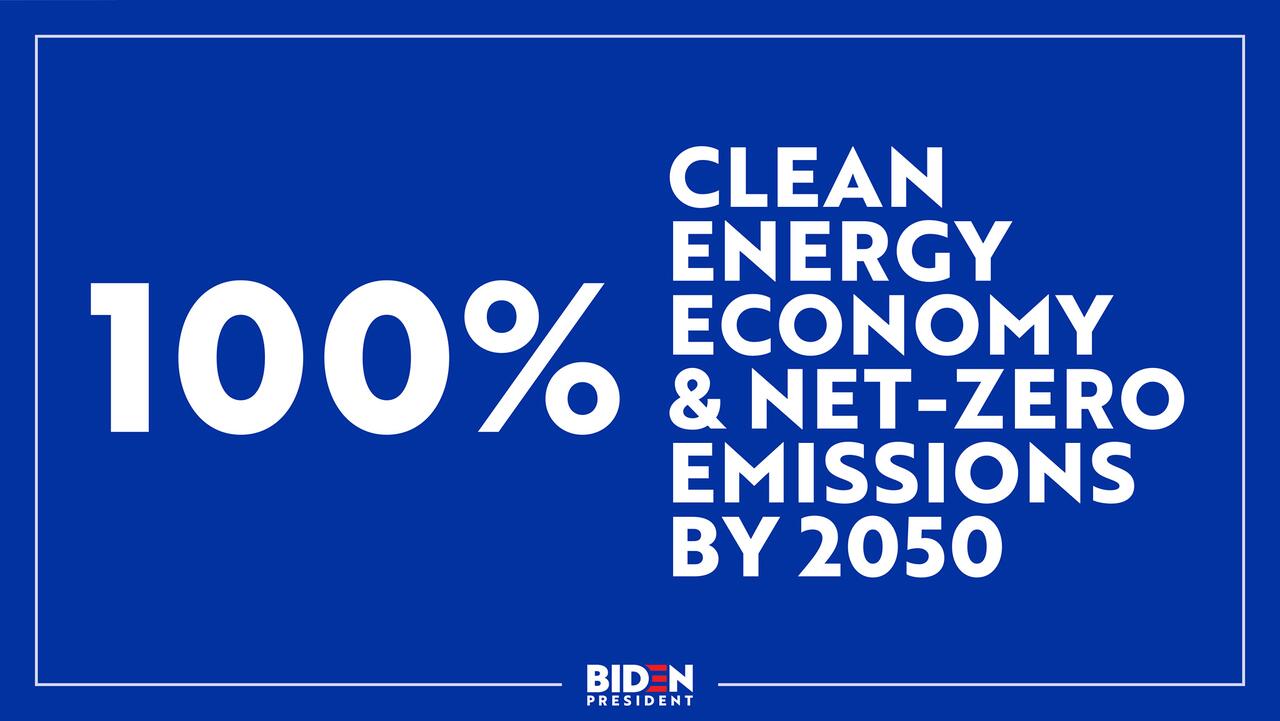

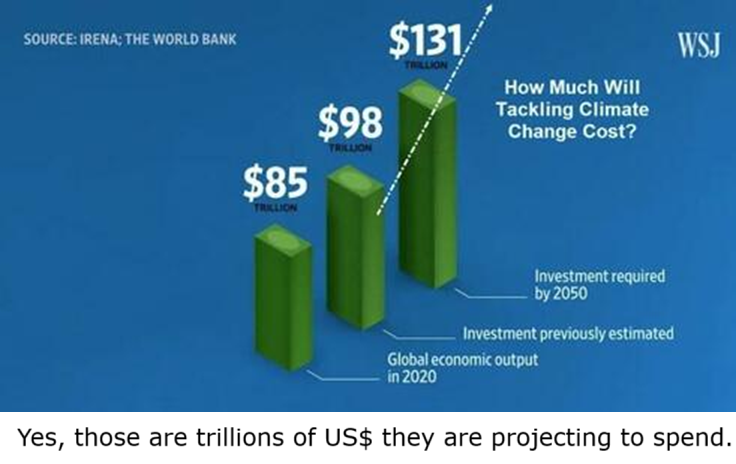

The public “net zero” pledges by countless corporate and political entities in recent years were always baffling. How could the United States or much of the industrialized world reach “net zero” emissions without destroying modern living?

As a reminder, “net zero” is a term coined to illustrate a goal of “eliminating greenhouse gas emissions produced by human activities, which is accomplished by decreasing global emissions and abating them from the atmosphere,” as defined by Net0.com, a company that describes itself as “the market leader in AI-First Sustainability, enabling governments and enterprises worldwide to enhance their environmental performance and decarbonize profitably.”

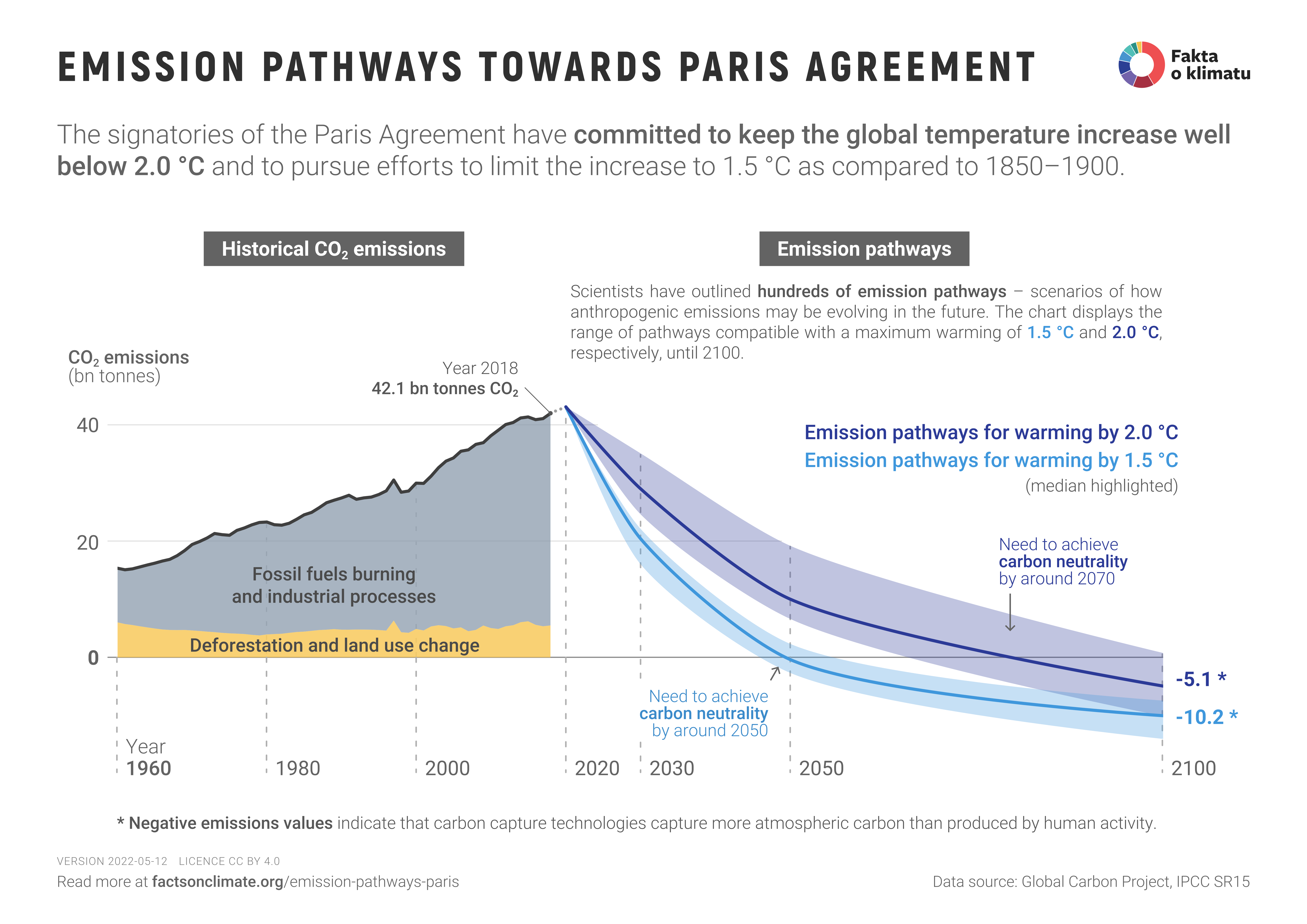

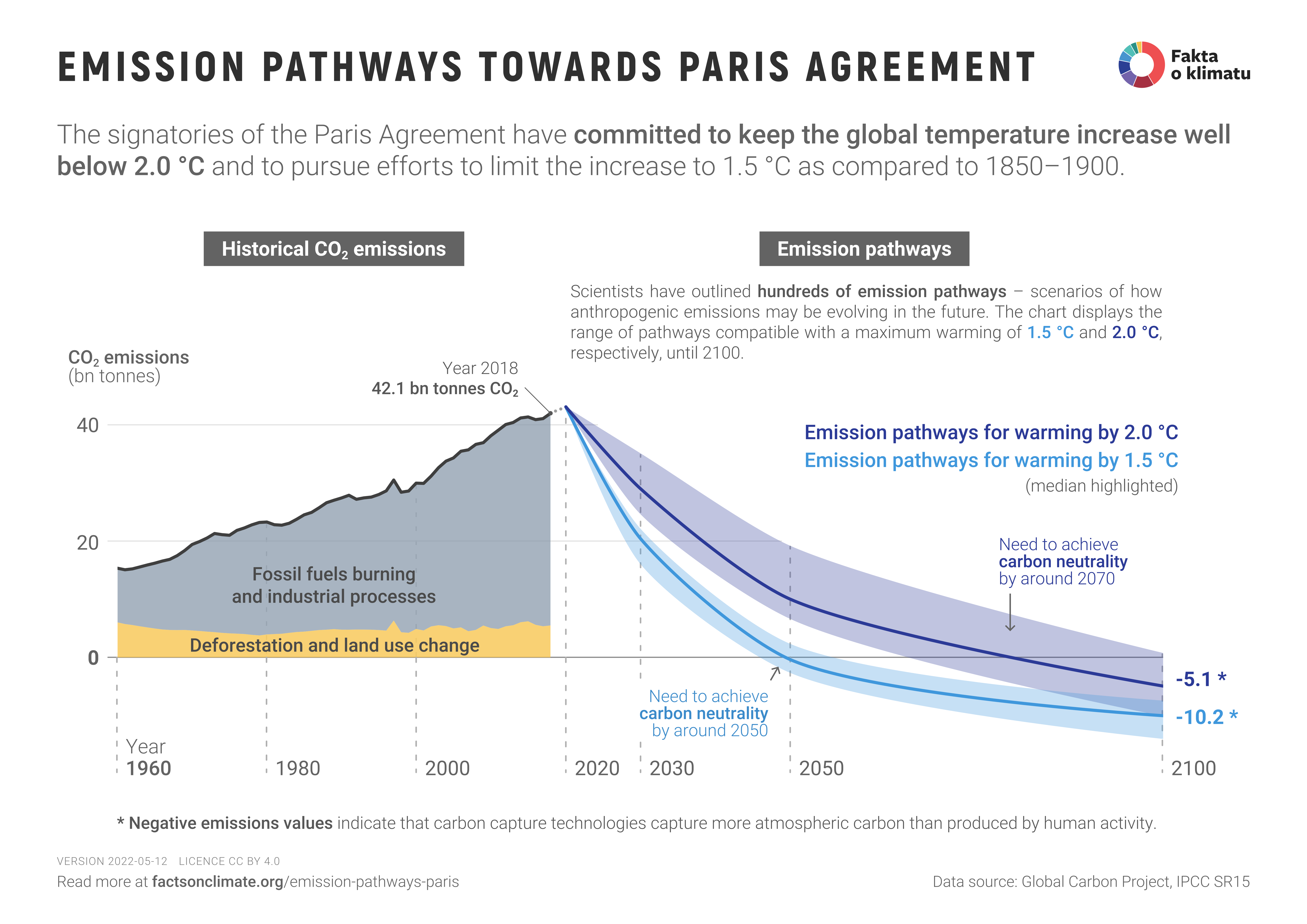

Net0 posits that “the global scientific community agrees that to mitigate the most severe impacts of climate change, we must reduce worldwide net human-generated carbon dioxide emissions by approximately 45 percent from their 2010 levels by the year 2030 and achieve net zero emissions by around 2050.”

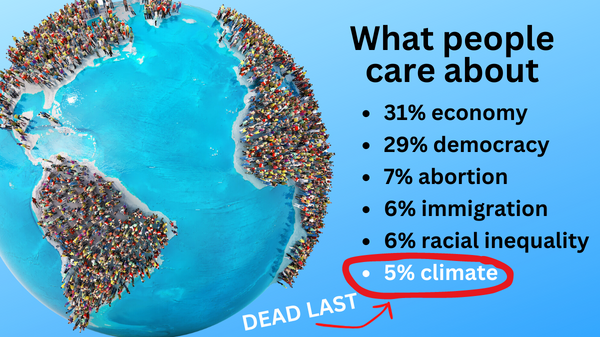

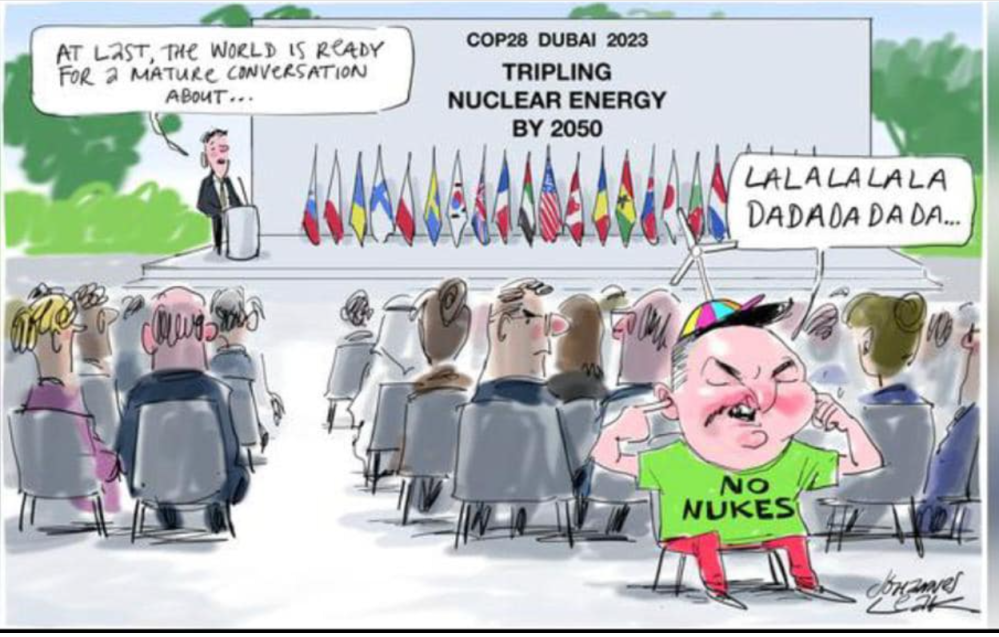

In a political atmosphere shaming anyone who didn’t join the climate cult – led in the U.S. by the Biden administration and globally by the U.N. – attempting to outdo each other for the most aggressive “net zero” policy was all the rage.

“As of June 2024, 107 countries… had adopted net-zero pledges either in law, in a policy document such as a national climate action plan or a long-term strategy, or in an announcement by a high-level government official,” boasted the United Nations.

“More than 9,000 companies, over 1,000 cities, more than 1,000 educational institutions, and over 600 financial institutions have joined the Race to Zero, pledging to take rigorous, immediate action to halve global emissions by 2030.”

But as politicians know, promises and actions are often unrelated. Most people endowed with even a modicum of common sense and a grade-school understanding of basic science knew that meeting “net zero” goals would require a reduction in the use of our most affordable, effective and reliable energy sources to a degree that would devastate modern economies.

The fact that “net zero” pledges were nothing but a cruel joke was made clear last month in a story by NPR headlined, “Leaders promised to cut climate pollution, then doubled down on fossil fuels.” Most thinking people were as surprised by that headline as by discovering wet water, hot fire or flying birds. It was not necessary to read further. “Of course,” they said to themselves, moving on to the next story.

But there are, sadly, climate cult converts who, in their shock, likely needed more details.

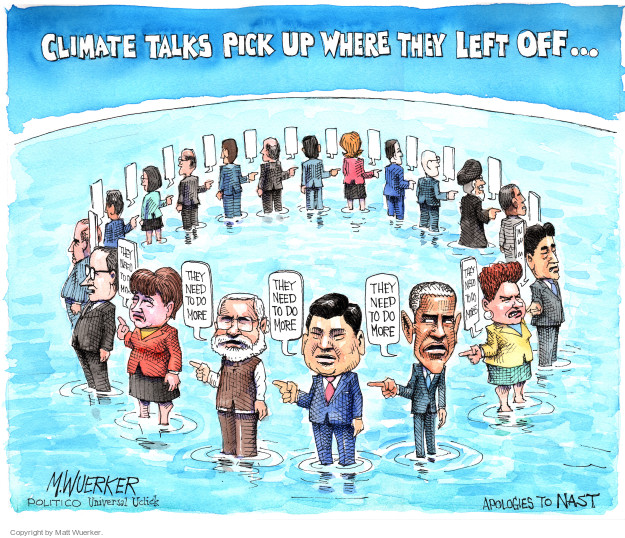

They discovered: “The world is producing too much coal, oil and natural gas to meet the targets set 10 years ago under the Paris Agreement, in which countries agreed to limit climate pollution and avoid the worst effects of global warming,” NPR reported. The story said:

“A new report, led by the nonprofit research group Stockholm Environment Institute, shows countries plan to produce more than twice the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than would be consistent with limiting global heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).”

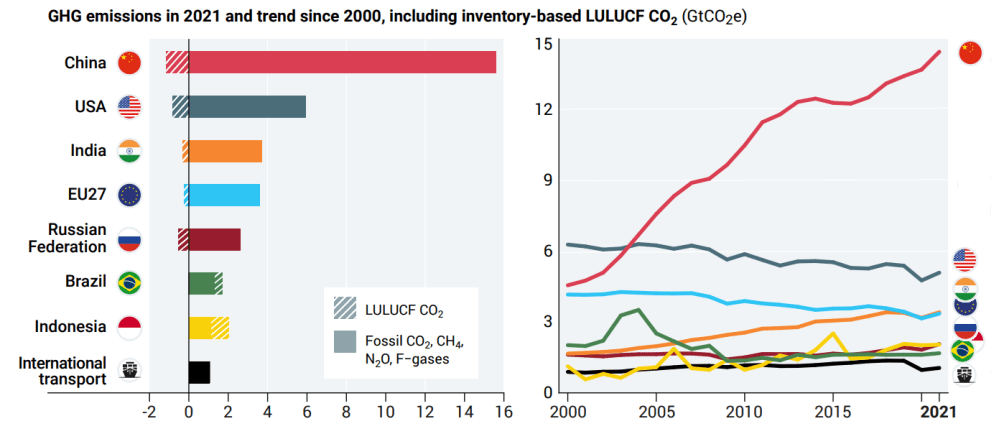

For the true believers, here’s the real punch to the gut: “The SEI report shows the 20 most polluting countries, including China, the U.S. and India, actually plan to produce even more fossil fuels than they did two years ago, when the report was last updated.”

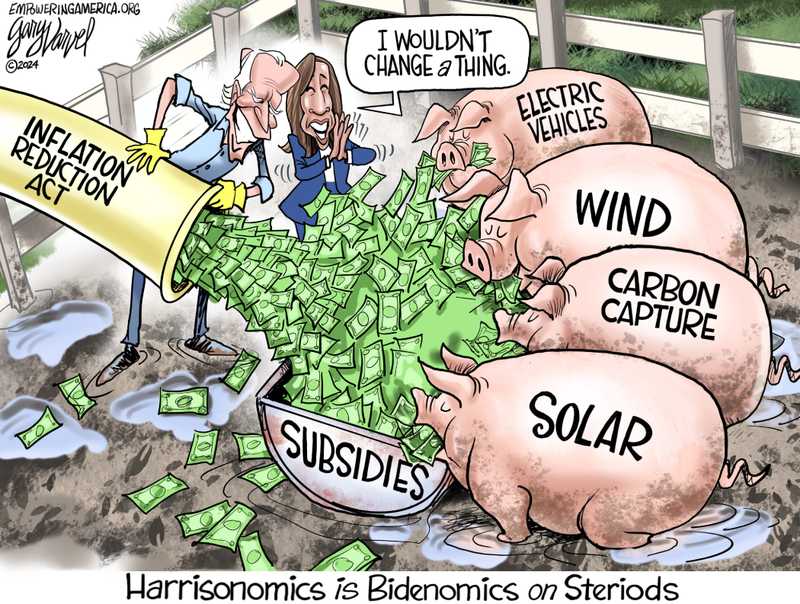

Of course, as he did in his first term, President Trump is pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement as he unleashes American industry and works to ensure energy affordability, independence and security for the nation. Legislation to roll back taxpayer subsidies for “renewables” and return to “reliables” has already been passed or introduced in various states and is soon likely to be fortified at the federal level.

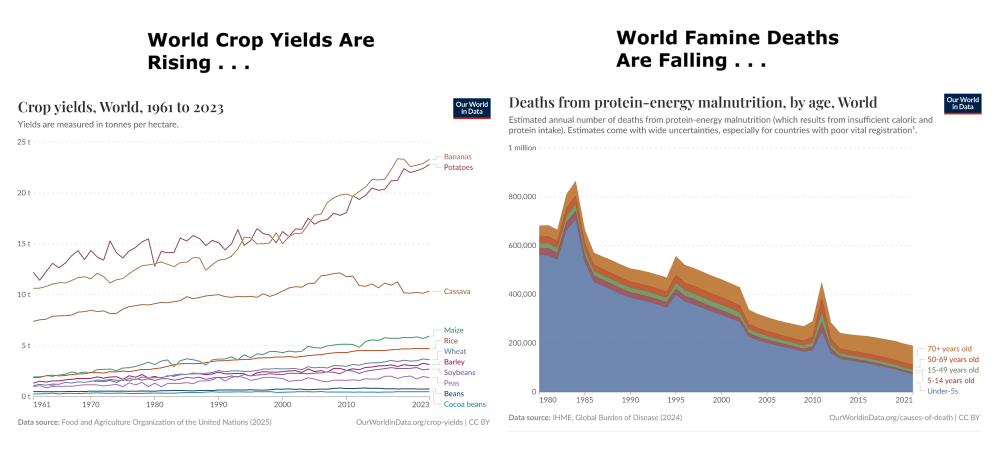

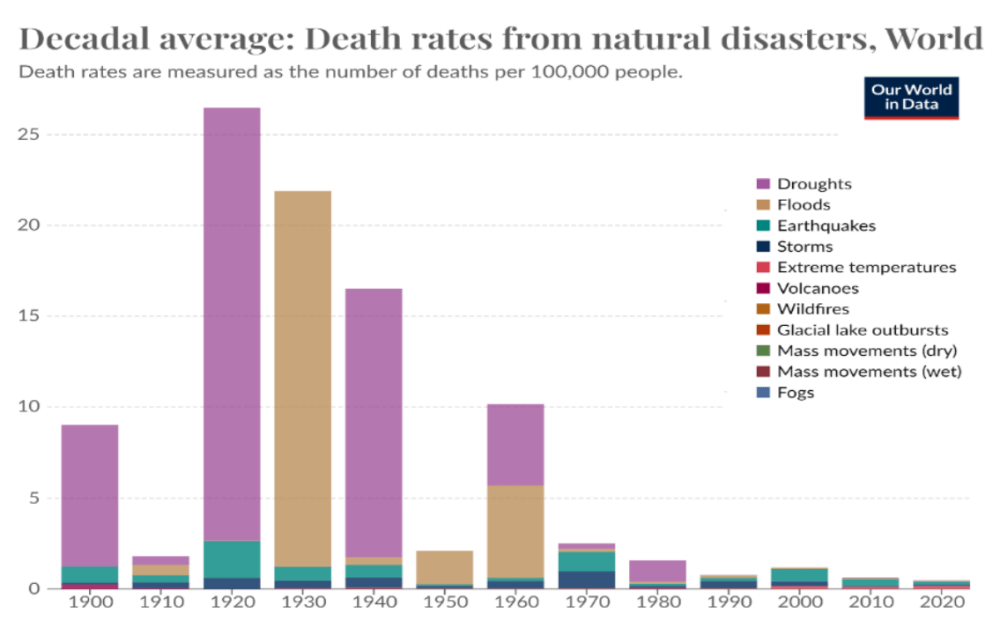

After wasting billions of tax dollars on wind and solar subsidies that could have been directed toward schools, healthcare or other real needs, the fever is finally breaking. The world is slowly but surely awakening from the delusions of climate zealots who insisted that we were on the verge of catastrophe with constantly worsening weather disasters.

Just last May, for example, NOAA the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted an “above-normal 2025 Atlantic hurricane season.” And just a few months earlier, PBS NewsHour reported on a study showing that “human-caused climate change made Atlantic hurricanes about 18 miles per hour (29 kilometers per hour) stronger in the last six years.”

The message was clear. More hurricanes.

Stronger hurricanes. This year’s reality so far?

“The 2025 Atlantic hurricane season is the first time in 10 years that a hurricane has not made landfall in the United States through the end of September,” according to American Press. While “hurricane season” extends through November, September is usually the busiest month.

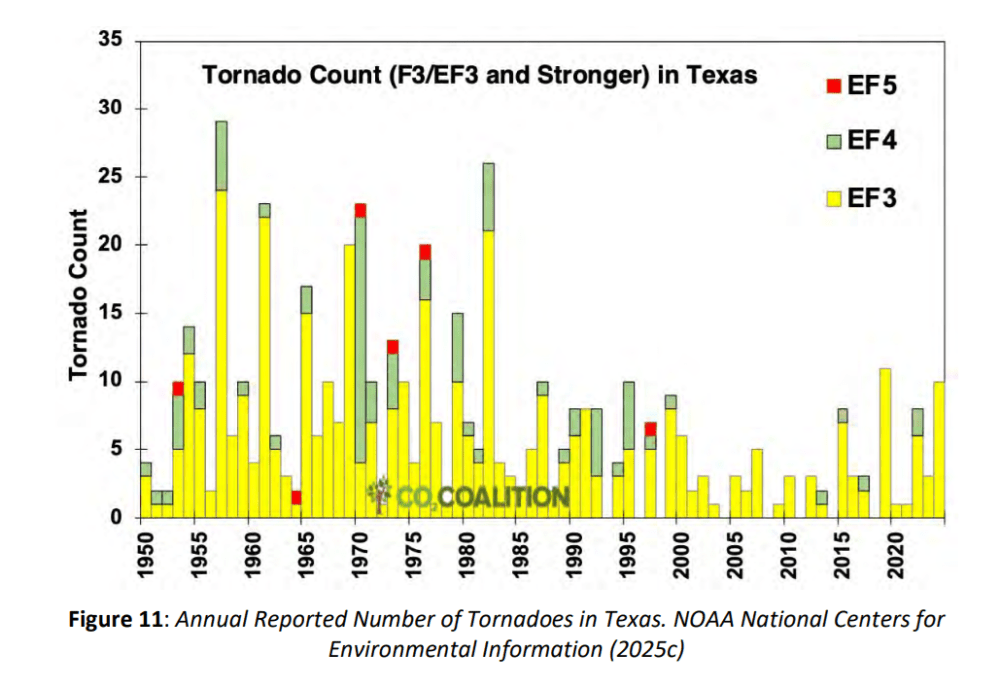

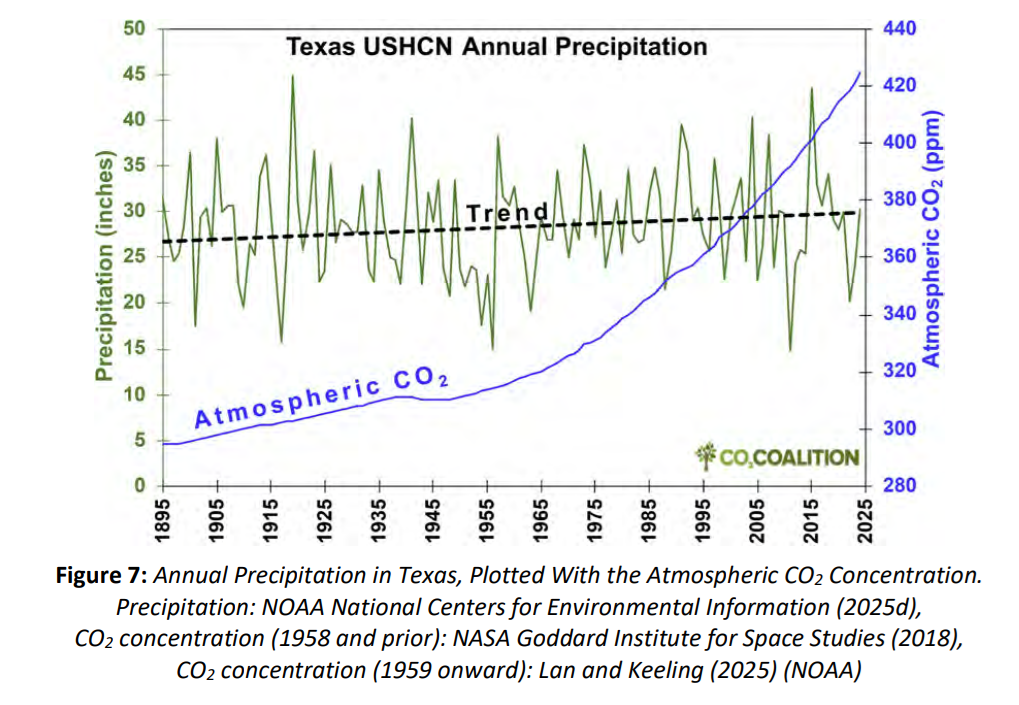

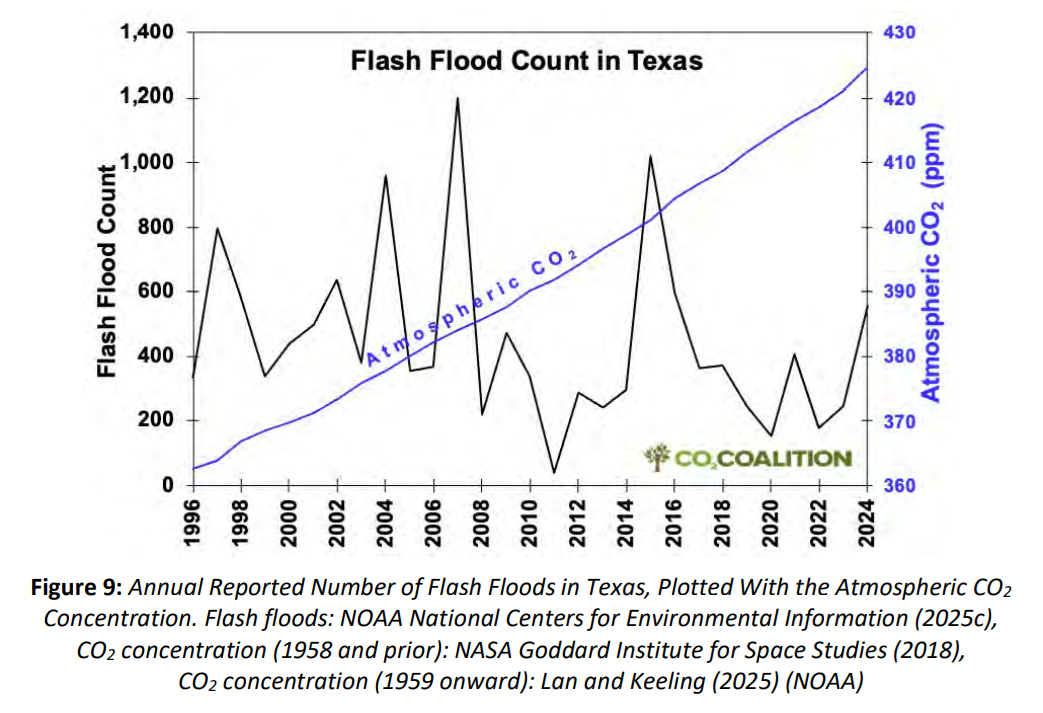

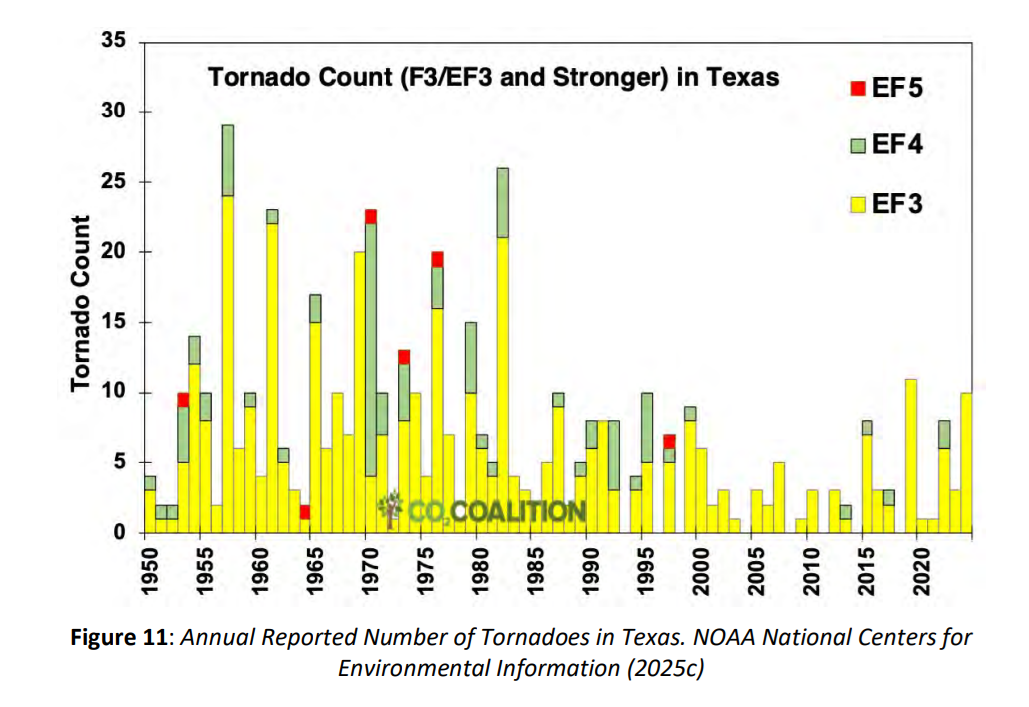

The weather is – and has always been – unpredictable. Severe weather events like hurricanes, tornadoes, monsoons, floods, blizzards and drought have always been with us, and always will. The attempt to demonize humankind for the frequency and severity of the weather has been politically motived and economically disastrous.

“Net zero” pledges are being revealed for the false promises they most often were, designed mainly to win plaudits from the Lecturing Left. For leaders grounded in facts, real-world needs have always meant that no one is easing off the gas.

2. Vaclav Smil’s paper is at Fraser Institute Halfway between Kyoto and 2050. Overview and keynote section are reprinted below with my bolds and added images.

Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

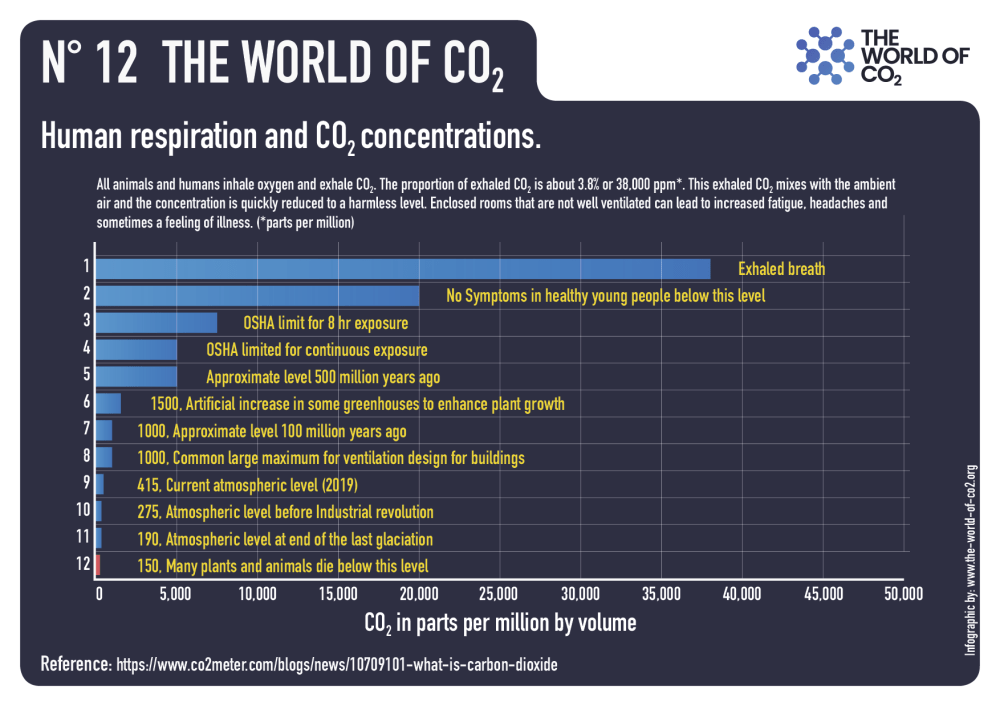

1. Carbon in the Biosphere

2. Energy Transitions

3. Our Record So Far

4. What It Would Take to Reverse the Past Emission Trend

5. The Task Ahead: Zero Carbon Electricity and Hydrogen

6. Costs, Politics, and Demand

7. Realities versus Wishful Thinking

8. Closing Thoughts

Executive Summary

♦ This essay evaluates past carbon emission reduction and the feasibility of eliminating fossil fuels to achieve net-zero carbon by 2050.

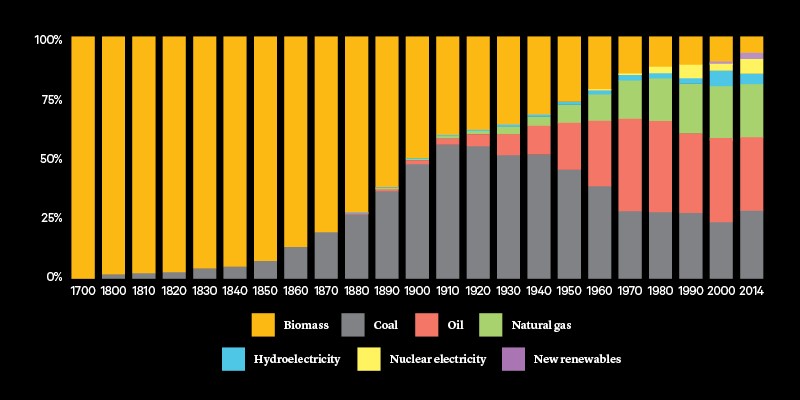

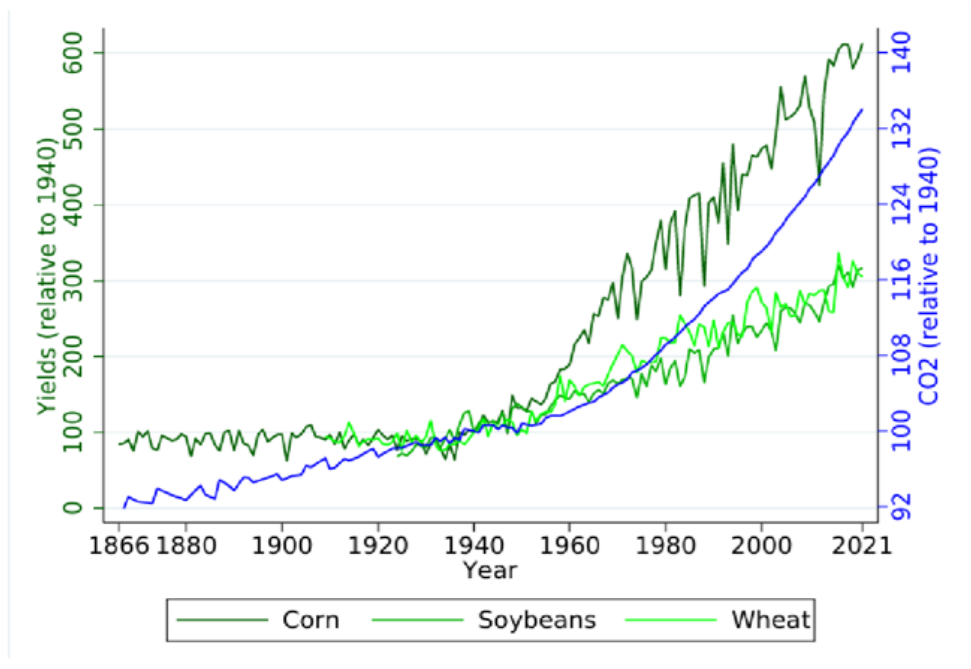

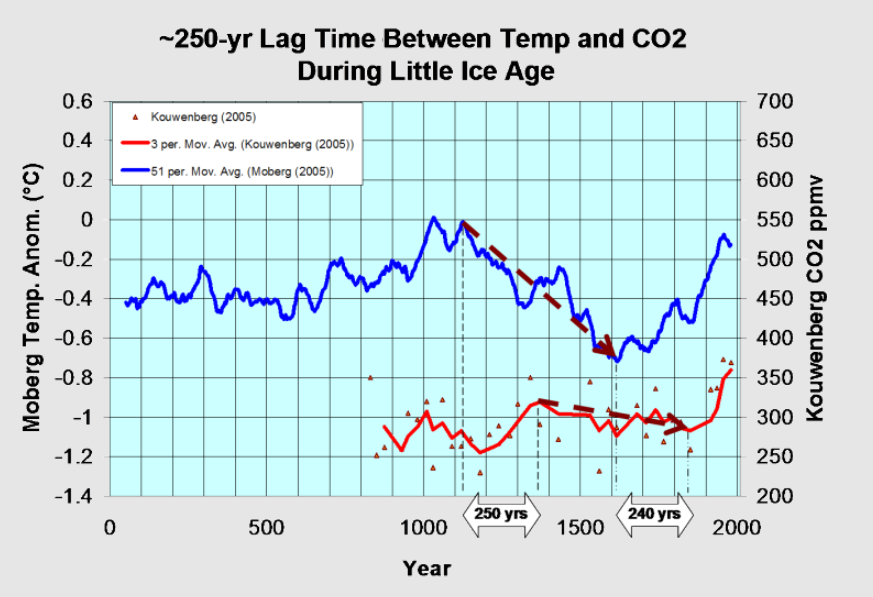

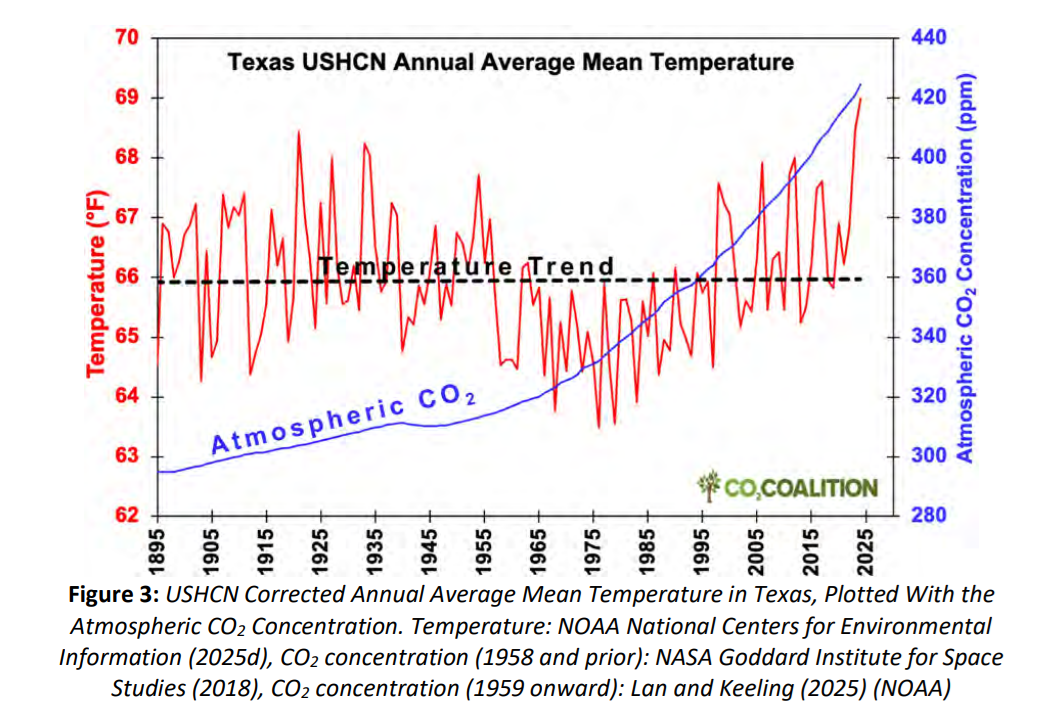

♦ Despite international agreements, government spending and regulations, and technological advancements, global fossil fuel consumption surged by 55 percent between 1997 and 2023. And the share of fossil fuels in global energy consumption has only decreased from nearly 86 percent in 1997 to approximately 82 percent in 2022.

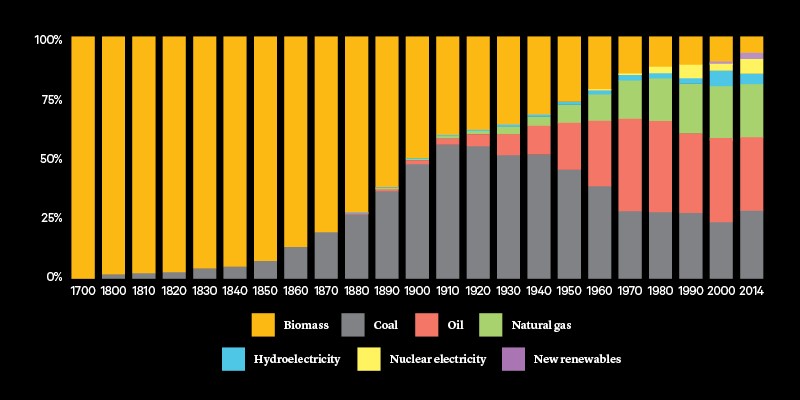

♦ The first global energy transition, from traditional biomass fuels such as wood and charcoal to fossil fuels, started more than two centuries ago and unfolded gradually.

♦ That transition remains incomplete, as billions of people still rely on traditional biomass energies for cooking and heating.

♦ The scale of today’s energy transition requires approximately 700 exajoules of new non-carbon energies by 2050, which needs about 38,000 projects the size of BC’s Site C or 39,000 equivalents of Muskrat Falls.

♦ Converting energy-intensive processes (e.g., iron smelting, cement, and plastics) to non-fossil alternatives requires solutions not yet available for largescale use.

♦ The energy transition imposes unprecedented demands for minerals including copper and lithium, which require substantial time to locate and develop mines.

♦ To achieve net-zero carbon, affluent countries will incur costs of at least 20 percent of their annual GDP.

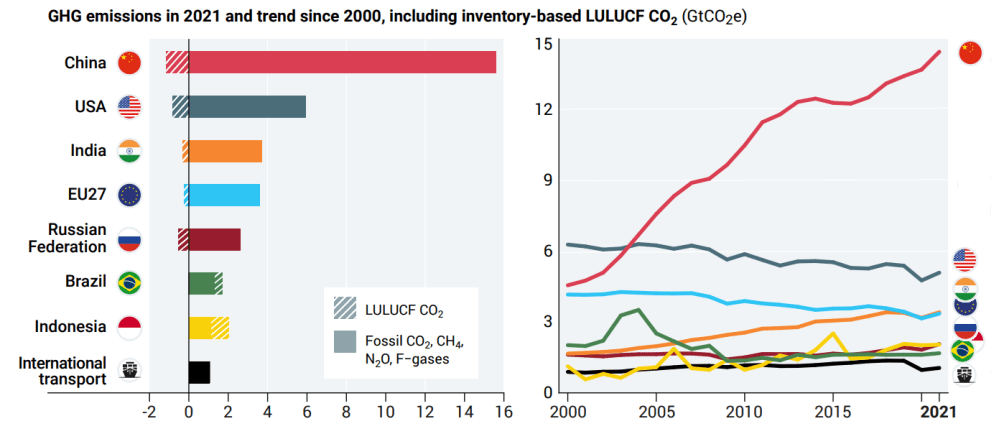

♦ While global cooperation is essential to achieve decarbonization by 2050, major emitters such as the United States, China, and Russia have conflicting interests.

♦ To eliminate carbon emissions by 2050, governments face unprecedented technical, economic and political challenges, making rapid and inexpensive transition impossible.

7. Realities versus Wishful Thinking

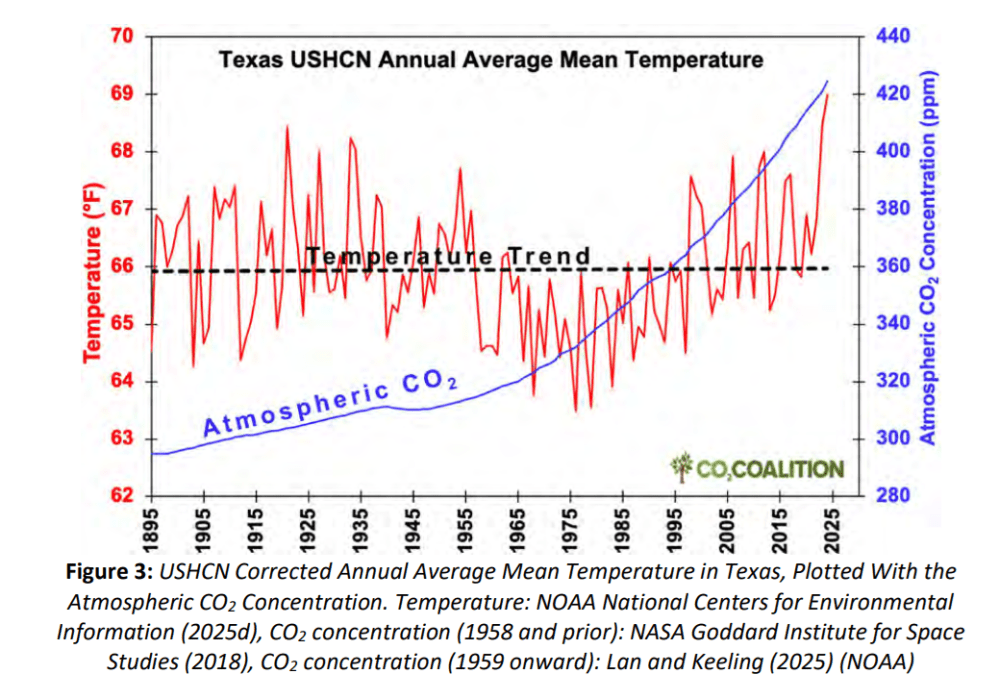

Since the world began to focus on the need to end the combustion of fossil fuels, we have not made the slightest progress in the goal of absolute global decarbonization: emission declines in many affluent countries were far smaller than the increased consumption of coal and hydrocarbons in the rest of the world, a trend that has also reflected the continuing deindustrialization in Europe and North America and the rising shares of carbon-intensive industrial production originating in Asia. As a result, by 2023 the absolute reliance on fossil carbon rose by 54 percent worldwide since the Kyoto commitment. Moreover, a significant part of emission declines in many affluent countries has been due to their deindustrialization, to transferring some of their carbon-intensive industries abroad, above all to China.

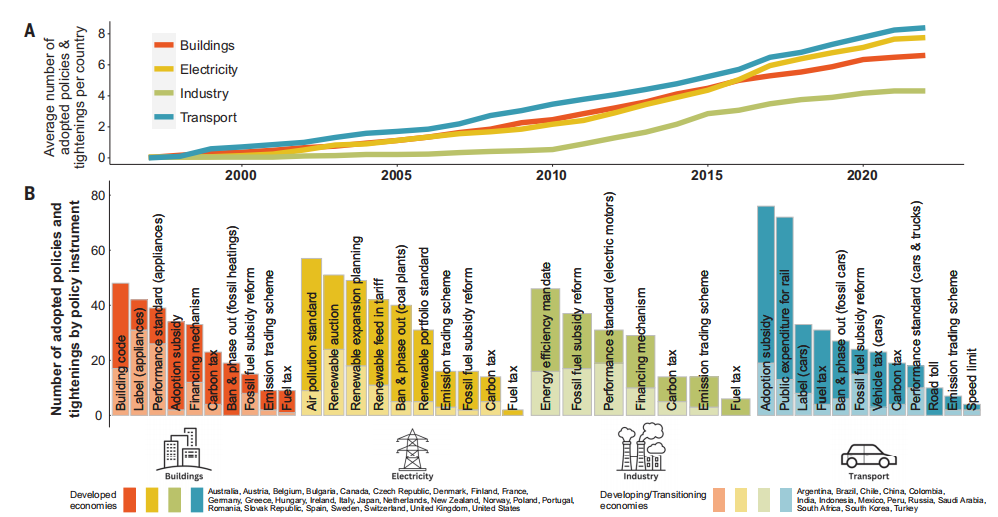

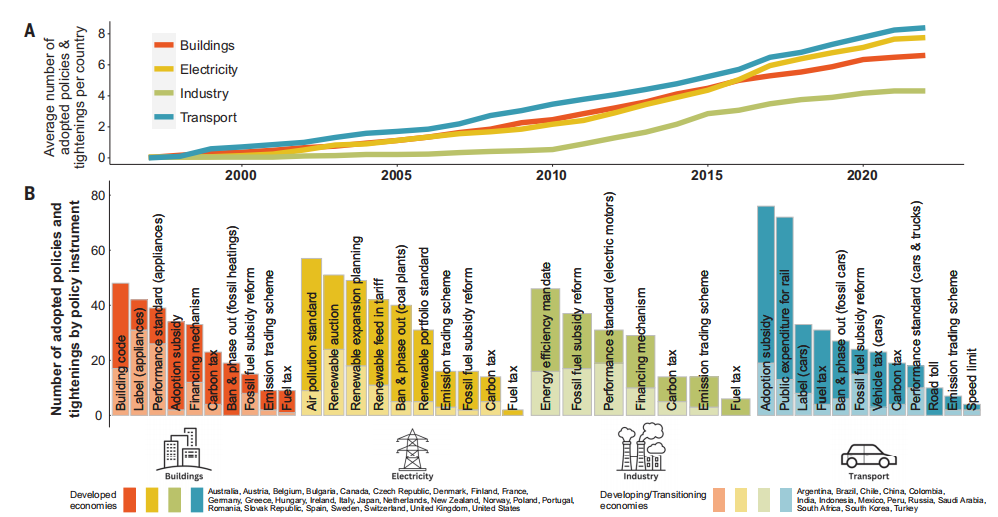

A recent international analysis of 1500 climate policies around the world concluded that 63 or 4% of them were successful in reducing emissions.

Denmark, with half of its electricity now coming from wind, is often pointed out as a particular decarbonization success: since 1995 it cut its energy-related emissions by 56 percent (compared to the EU average of about 22 percent)—but, unlike its neighbours, the country does not produce any major metals (aluminum, copper, iron, or steel), it does not make any float glass or paper, does not synthesize any ammonia, and it does not even assemble any cars. All these products are energy-intensive, and transferring the emissions associated with their production to other countries creates an undeservedly green reputation for the country doing the transferring.

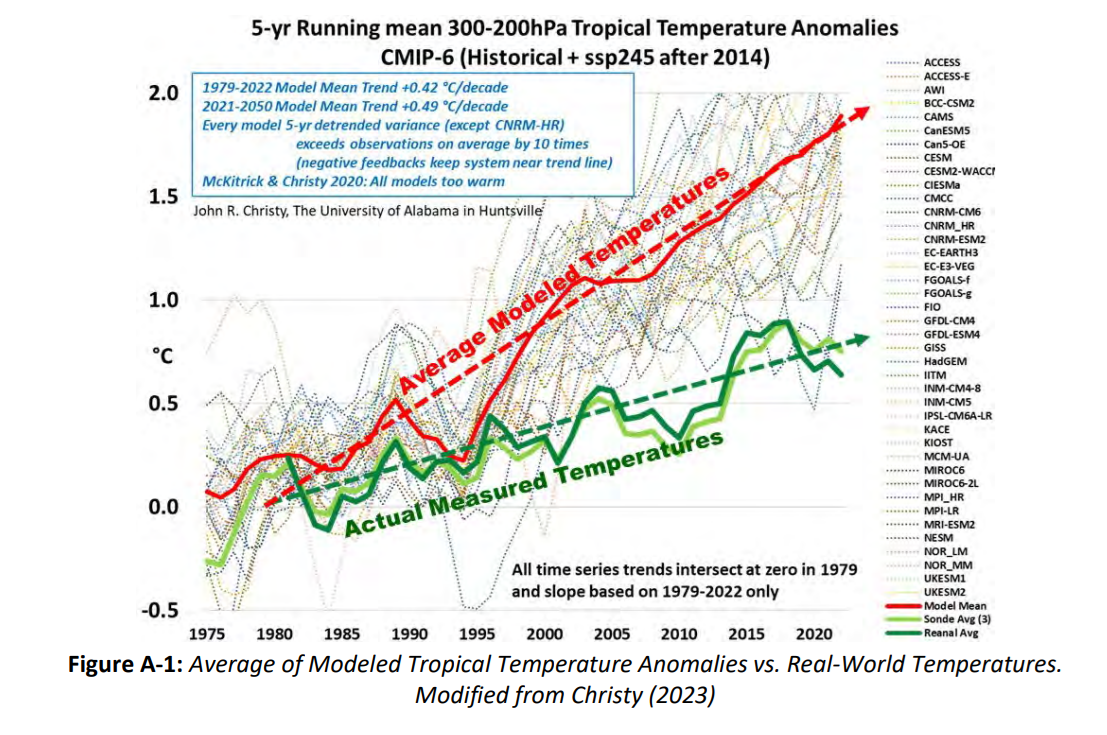

Given the fact that we have yet to reach the global carbon emission peak (or a plateau) and considering the necessarily gradual progress of several key technical solutions for decarbonization (from large-scale electricity storage to mass-scale hydrogen use), we cannot expect the world economy to become carbon free by 2050. The goal may be desirable, but it remains unrealistic. The latest International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook report confirms that conclusion. While it projects that energy-related CO2 emissions will peak in 2025, and that the demand for all fossil fuels will peak by 2030, it also anticipates that only coal consumption will decline significantly by 2050 (though it will still be about half of the 2023 level), and that the demand for crude oil and natural gas will see only marginal changes by 2050 with oil consumption still around 4 billion tons and natural gas use still above 4 trillion cubic meters a year (IEA, 2023d).

Wishful thinking or claiming otherwise should not be used or defended by saying that doing so represents “aspirational” goals. Responsible analyses must acknowledge existing energy, material, engineering, managerial, economic, and political realities. An impartial assessment of those resources indicates that it is extremely unlikely that the global energy system will be rid of all fossil carbon by 2050. Sensible policies and their vigorous pursuit will determine the actual degree of that dissociation, which might be as high as 60 or 65 percent. More and more people are recognizing these realities, and fewer are swayed by the incessant stream of miraculously downward-bending decarbonization scenarios so dear to demand modelers.

Long-term global energy forecasts offering numbers for overall demand or supply and for shares contributed by specific sources or conversions are beyond our capability: the system is too complex and too open to unforeseen but profound perturbations for such specificity. However, skepticism in constructing long-term estimates will lessen the extent of inevitable errors. Here is an example of a realistic 2023 forecast done by Norwegian risk management company DNV that has been echoed recently by other realistic assessments. After noting that global energy-related emissions are still climbing (but might peak in 2024 when the transition would effectively begin) it concludes that by 2050 we will move from the present roughly 80 percent fossil/20 percent non-fossil split to a 48 percent/52 percent ratio by 2050, with primary energy from fossil fuels declining by nearly two-thirds but still remaining at about 314 EJ by 2050—in other words, about as high as it was in 1995 (DNV, 2023).

Again, that is what any serious student of global energy transitions would expect. Individual components change at different speeds and notably rapid transformations are possible, but the overall historical pattern quantified in terms of primary energies is one of gradual changes. Unfortunately, modern forecasting in general and the anticipation of energy advances in particular have an unmistakable tendency toward excessive optimism, exaggeration, and outright hype (Smil, 2023b). During the 1970s many people believed that by the year 2000 all electricity would come not just from fission, but from fast breeder reactors, and soon afterwards came the promises of “soft energy” taking over (Smil, 2000).

Belief in near-miraculous tomorrows never goes away. Even now we can read declarations claiming that the world can rely solely on wind and PV by 2030 (Global100REStrategyGroup, 2023). And then there are repeated claims that all energy needs (from airplanes to steel smelting) can be supplied by cheap green hydrogen or by affordable nuclear fusion. What does this all accomplish besides filling print and screens with unrealizable claims? Instead, we should devote our efforts to charting realistic futures that consider our technical capabilities, our material supplies, our economic possibilities, and our social necessities—and then devise practical ways to achieve them. We can always strive to surpass them—a far better goal than setting ourselves up for repeated failures by clinging to unrealistic targets and impractical visions.