Carbon Tax Dubious Economics

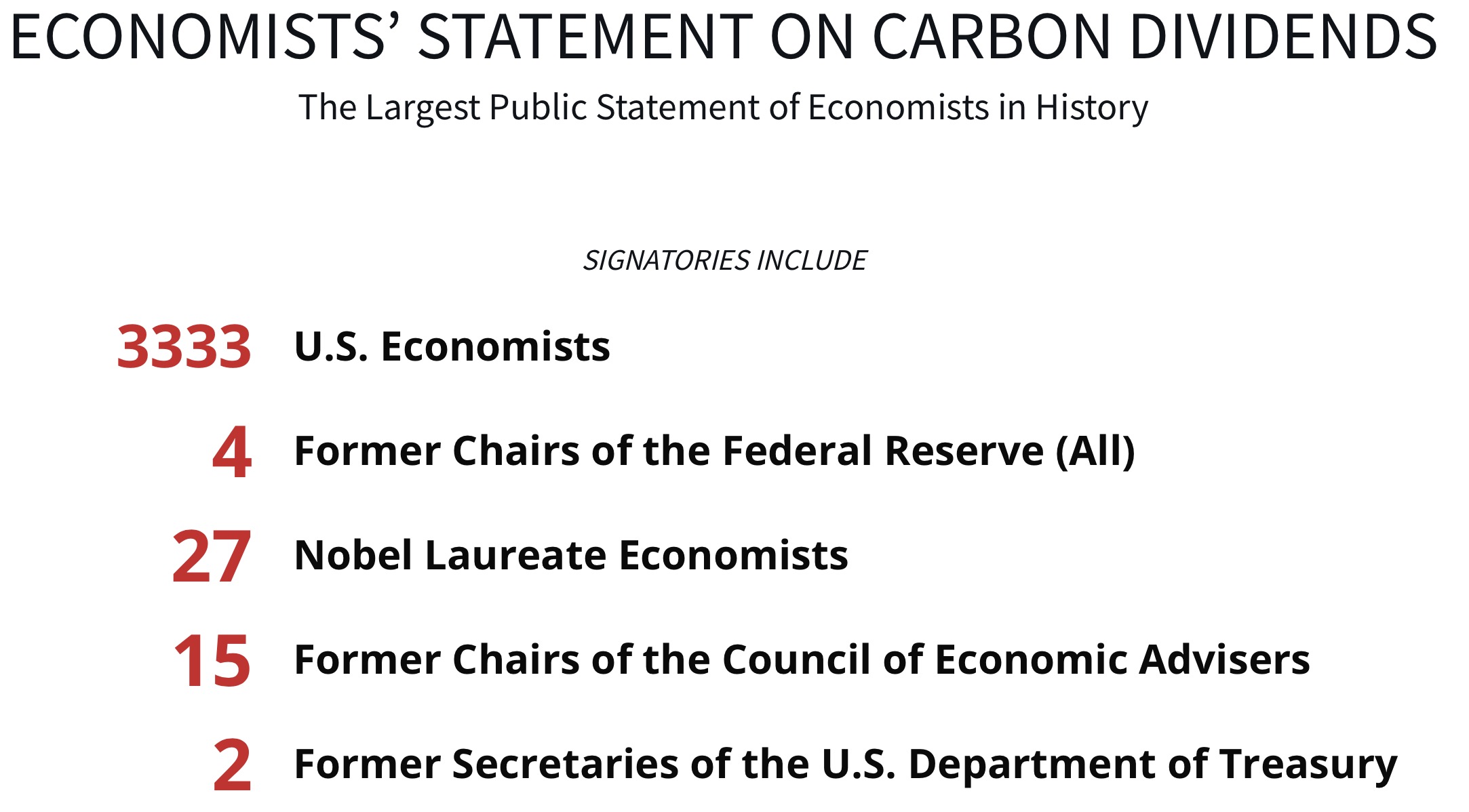

How could 3508 economists be wrong? Let us count the ways.

Michael Davis writes at Regulation Magazine The signatories of the recent “Economists’ Statement on Carbon Dividends” must address some important issues. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Economists are disagreeable people. And it’s good that they are. Most important economic questions are complex, multi-dimensional puzzles with no obvious, simple answers. But debate and disagreement advance our understanding of the world, and so good economists debate and disagree.

If you heard that thousands of the very best economists actually did agree on something, you’d probably think that it was something glaringly obvious—maybe they issued a joint statement condemning the designated hitter rule or calling for a total ban on Super Bowl halftime shows. But those aren’t the subject of the recent “Economists’ Statement on Carbon Dividends,” signed by 3,508 economists and released by the Climate Leadership Council. The statement supports the creation of a Pigouvian tax on U.S. carbon emissions on the grounds that “global climate change is a serious problem calling for immediate national action,” and that “a carbon tax offers the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary.”

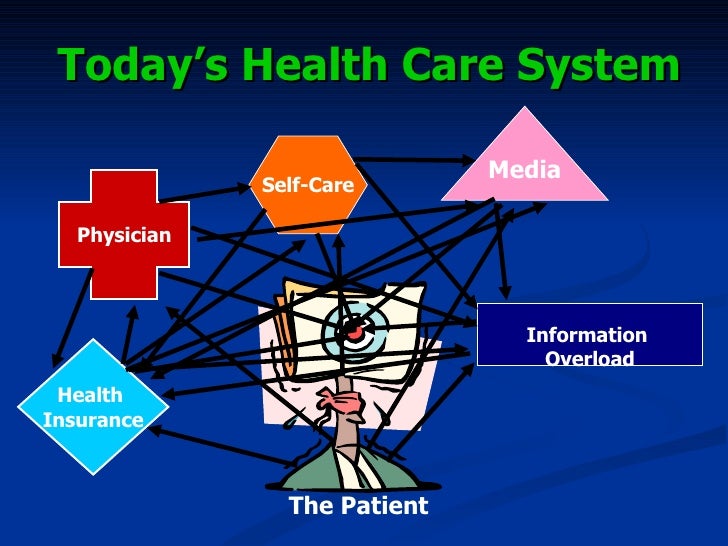

This agreement is remarkable! The environment and the economy are both complex systems. Intelligent people can agree on a few things involving them—of course, manmade global warming is real—but there is vast uncertainty about how the complex climate system interacts with the complex economic system to shape the human condition in the distant future. More importantly, core questions about climate change engage fundamental moral values about intergenerational equity. How to deal with climate change is the very epitome of a “wicked problem.”

[Note: Intelligent people also note that in the world (as opposed to models) manmade global warming has yet to be detected separately from natural global warming. I understand the author is not questioning the science or the impacts (later on), but is raising serious issues about the policy proposal.]

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4192727/climate-change-uncertainty-loop.0.jpg)

This is a serious proposal advanced by serious people to deal with a serious problem. But it is also a radical proposal. According to a joint study by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and the Urban Institute–Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, in the first year the tax would amount to about $2,000 for a family of four. No matter what is done with the tax revenues, this proposal would have far-reaching economic consequences.

And so, before we get too far along, we need a proper argument over this proposal’s merits. Here, then, are five important questions about the plan. Let’s hope these questions lead to some disagreeable, but fruitful, discussions.

QUESTION 1: What if these economists are right about the principle but wrong about the tax rate?

The principle behind the carbon tax makes perfect economic sense. The market price of any good reflects at least some of the costs of making that good. The price of a gallon of gas, for example, needs to be high enough to compensate all those who worked to get the gas into your car. But some goods—and gasoline is one of them—impose costs on others that are not reflected in the price. Economists call these costs “negative externalities.” If burning a gallon of gas causes damage to coastal property, drivers are not paying the full price of their consumption and that distorts their consumption choices. That’s unfair and inefficient.

The obvious solution is to levy a Pigouvian tax equal to the harm caused, forcing consumers to shoulder the externality cost of their consumption and, perhaps, change their consumption pattern. But we have very little idea of the magnitude of the actual harm from a ton of CO2 emissions and so we don’t really know how high this carbon tax should be. Estimates of the “Social Cost of Carbon” published by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency indicate that a ton of CO2-equivalent released in 2020 could cause harm of as little as $5 or as much as $123. (This roughly translates to a range of between 4¢ and $1 of damage from the burning of a gallon of gas.) The $40-per-ton tax suggested by the Statement signatories is a kind of average of several disparate estimates. As such, it is almost certainly the wrong number.

These economists will, no doubt, point out that the current carbon tax of zero is also wrong. But that observation, alone, is not enough to justify the proposed tax because setting the rate in excess of the actual external harm would cause real economic damage.

The economic argument in favor of carbon taxes needs to be coupled with a clear understanding that cheap, abundant energy has been an essential part of recent human progress. Fossil fuels provide food, shelter, health care, education, the arts, and countless other goods. They are not some vile poison, and consuming fossil fuels is not a shameful sin. When something is taxed, less is consumed. If, as seems likely, we consume too much energy from carbon-based resources, a tax can help to moderate that consumption appropriately. But if the tax is too high, we will consume too little. If we consume too little, we will miss out on some of the benefits that come from fossil fuels.

Here’s another problem related to the practical question of the appropriate carbon tax rate: Many fossil fuels are already heavily taxed. For example, the average tax on motor fuels is now about 48¢ per gallon, the equivalent to a tax of $54 per ton of carbon. These taxes exist mostly to raise revenue for transportation infrastructure, not control some other externality. Should the proposed new carbon tax be in addition to those existing taxes?

QUESTION 2: Should the United States impose carbon taxes even if the rest of the world does not?

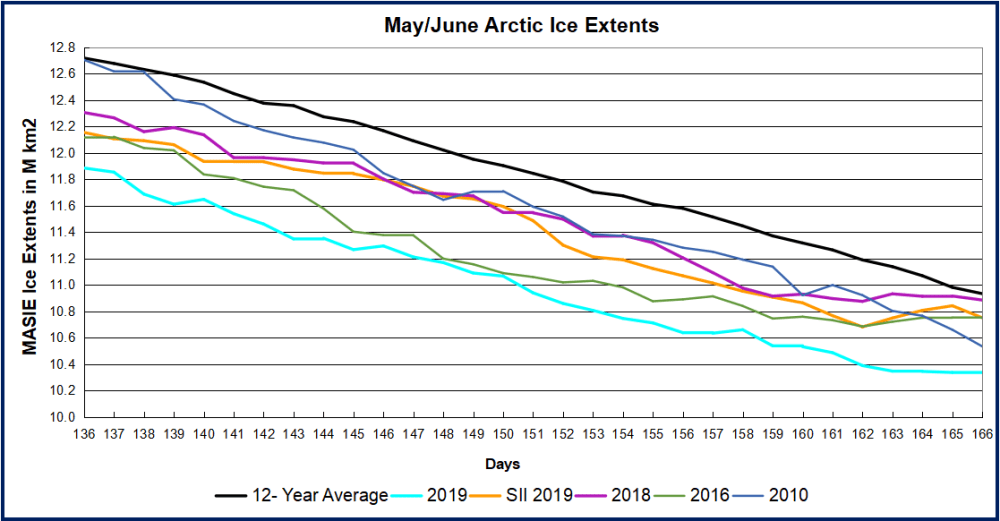

In 2019 the world will produce a bit more than 35 gigatons of CO2-equivalent emissions. The United States will contribute about 5 gigatons to that total. The U.S. Department of Energy forecasts that, in 2040, world emissions will increase to 43 gigatons while U.S. emissions will drop by a small amount. A 2018 report by the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University forecasts that if we impose a tax of $50 per ton of carbon in 2020 and increase that tax by 2% per year, annual U.S. emissions will fall by 13%–29% by 2030. But by 2030, U.S. emissions will be less than 15% of the world total. Even under the best-case scenario, our carbon tax would reduce global emissions by less than 5% and climate change will continue.

If the rest of the world doesn’t join us, the U.S. carbon tax won’t matter. This leads to a related problem. If the United States levies a carbon tax, it becomes more expensive for U.S. firms to make and transport goods. That means a U.S. carbon tax will reward those countries that don’t do anything to reduce their emissions by giving those places a competitive advantage. Exploiting that advantage will likely be too much of a temptation for others—especially developing countries with desperately poor people—to ignore. It is even possible that by pushing energy-intensive production to places with no controls on carbon emissions, this policy will make global emissions worse.

QUESTION 3: Doesn’t the “border-adjustment tax” that has to be part of the plan present enormous practical and political problems?

This carbon tax should not just apply to U.S. emissions, but to foreign emissions resulting from goods imported into the United States. Assessing a border-adjustment tax on these goods would be difficult from both an economic and political perspective. For example, almost 5% of the world’s carbon emissions result from the production of cement. But different production technologies for cement and different modes of transportation result in vastly different emissions. Even though two different shipments of cement may be practically identical, they won’t have similar carbon footprints. How would U.S. authorities determine which bags of cement face what tax rates?

The political problems are also tough. First of all, to the rest of the world a border-adjustment tax would seem like a tariff. How would we impose this tax without violating treaty obligations and without inviting retaliation? Second, how would we keep the crony capitalists away from the treats? The temptation to game the system for competitive advantage would be enormous.

QUESTION 4: What about adaptation?

All but the most apocalyptic of the potential harms from global warming can be managed through some type of adaptation to the changing climate. Building practices, for example, can be changed to deal with the threat of rising sea levels. There is also the possibility of some sort of geo-engineering solution. Remember that atmospheric CO2 is an otherwise harmless substance and that the burning of fossil fuels is enormously valuable. This means that if it is less costly to adapt to the effects of a ton of CO2 emissions than it is to eliminate the carbon, we should adapt. But to the extent that the carbon tax actually works to reduce CO2 emissions, it creates disincentives to adapt.

The proponents of a tax might say that the estimates of the Social Cost of Carbon already balance adaptation costs. The problem with that argument, though, is that the most effective adaptation solutions probably haven’t been created. New technologies to deal with climate change—altering agriculture practices, geo-engineering solutions, and other initiatives we can’t currently imagine— may well prove extraordinarily effective and efficient. An effective carbon tax reduces the incentive to find those solutions that allow us to enjoy the benefits of fossil fuel use without much cost.

QUESTION 5: Isn’t economic growth much more important than lowering CO2?

Every four years, a distinguished group of analysts delivers to Congress the “National Climate Assessment.” The latest version came out last November and was full of sobering projections. Anyone who chooses to ignore the threat of global warming should read what it has to say. Among the direst warnings was a graphic showing that if the worst-case scenario played out, by 2100 the effects of global warming would reduce U.S. gross domestic product by about 15% from current projections. To put that number in perspective, during the 2008 recession GDP fell by about 1%. That was accompanied by huge increases in unemployment and economic dislocation. Between 1929 and 1933, the worst years of the Great Depression, GDP fell by about 34%. That led to tremendous misery and, arguably, a world war. Remember, too, that the potential decline of 15% of GDP in 2100 isn’t just a short-term event. As bad as the Great Depression was, the economy recovered. The scary scenario is that by failing to address global warming, we will cause future generations to suffer a huge permanent decline in GDP.

But there’s another thing to keep in mind: if the United States could boost annual GDP growth rates between now and 2100 by an additional 0.2 percentage points, by the year 2100 U.S. GDP would be more than 17% larger than is currently projected. Think about it this way: Suppose that you had to pick between two tax policies. The first would reduce U.S. carbon emissions and maybe prevent the potential loss of 15% of GDP by 2100. The second would increase annual growth rates by 0.2 percentage points, increasing GDP by 17% by 2100.

As you’re picking between the choices, keep in mind that even if the carbon policy controls U.S. emissions, it is uncertain whether the rest of the world will go along and climate change will stop. Remember, too, that there is huge uncertainty about the specifics of global warming. The carbon emissions policies target the worst-case scenario. The GDP growth policy, on the other hand, doesn’t depend on the rest of the world and the benefits are guaranteed by the simple mathematics of compound growth.

Don’t try to waive off this choice by saying you want to do it all. We all want many things, but what we can have is bounded by our scarce resources. This particular group of distinguished economists has—quite deservedly—an impressive stock of political capital and prestige. But political capital and prestige are two such scarce resources. Why target carbon taxes rather than growth-enhancing tax reform?

CONCLUSION

Let’s end where we started, with a call for a conversation. These five questions aren’t intended as some snarky put-down of a silly economic proposal. No good economist—and certainly none of the 3,508 who signed the Statement—should feel disrespectfully challenged by these questions. There are intelligent responses to each of these questions. And at the end of the discussion, we should all have a better idea about whether the answers are good enough to go ahead with the tax.

Highlights

Highlights

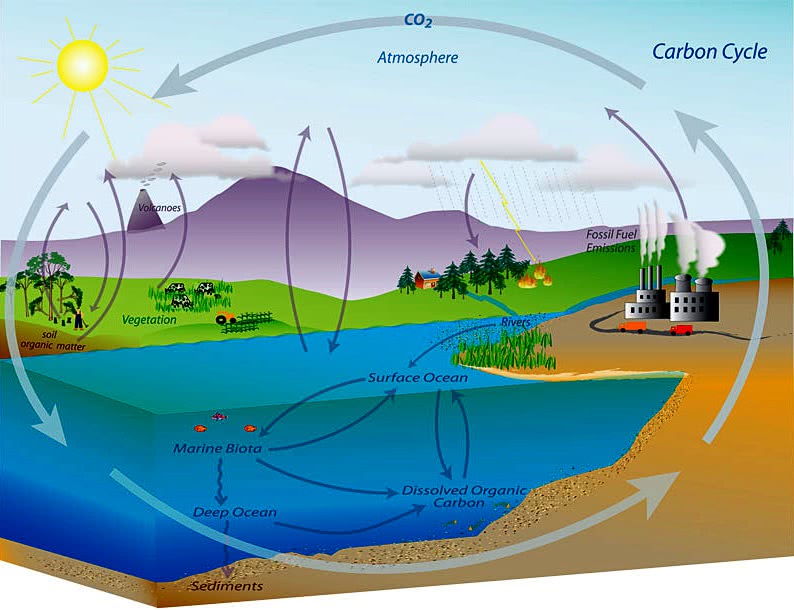

Fig. 1. Simplified schematic of the global carbon cycle. Black numbers and arrows indicate reservoir mass in PgC and exchange fluxes in PgC/yr before the Industrial Era. Red arrows and numbers show annual anthropogenic’ flux changes averaged over the 2000–2009 time period. Graphic from AR5-Chap.6-Fig.6.1.

Fig. 1. Simplified schematic of the global carbon cycle. Black numbers and arrows indicate reservoir mass in PgC and exchange fluxes in PgC/yr before the Industrial Era. Red arrows and numbers show annual anthropogenic’ flux changes averaged over the 2000–2009 time period. Graphic from AR5-Chap.6-Fig.6.1.