What Are Lost Continents, and Why Are We Discovering So Many? Is published at The Conversation by By Simon Williams, Joanne Whittaker & Maria Seton. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

What Are Lost Continents, and Why Are We Discovering So Many? Is published at The Conversation by By Simon Williams, Joanne Whittaker & Maria Seton. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

For most people, continents are Earth’s seven main large landmasses.

But geoscientists have a different take on this. They look at the type of rock a feature is made of, rather than how much of its surface is above sea level.

In the past few years, we’ve seen an increase in the discovery of lost continents. Most of these have been plateaus or mountains made of continental crust hidden from our view, below sea level.

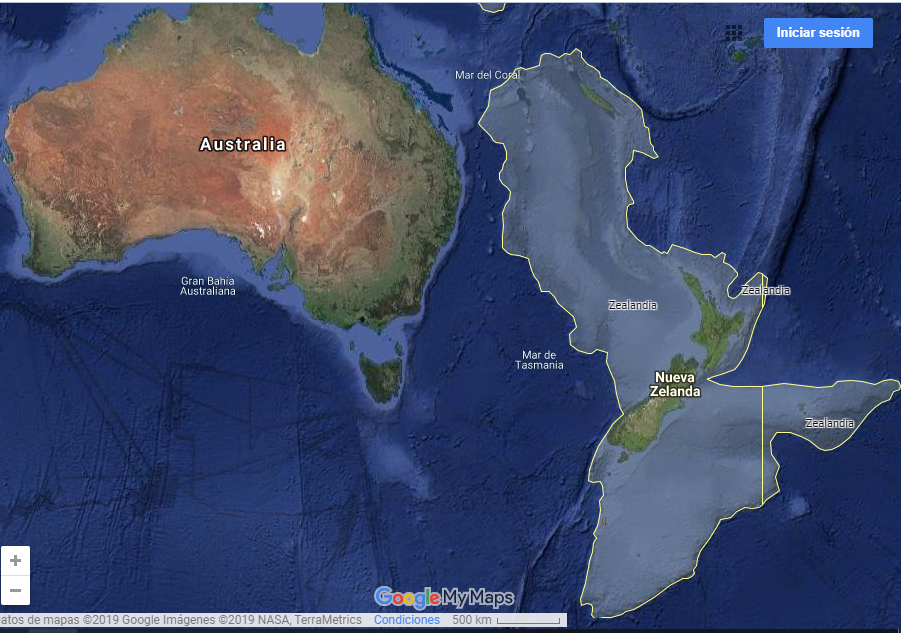

One example is Zealandia, the world’s eighth continent that extends underwater from New Zealand.

Several smaller lost continents, called microcontinents, have also recently been discovered submerged in the eastern and western Indian Ocean.

Several smaller lost continents, called microcontinents, have also recently been discovered submerged in the eastern and western Indian Ocean.

But why, with so much geographical knowledge at our fingertips, are we still discovering lost continents in the 21st century?

Down to the details

There are many mountains and plateaus below sea level scattered across the oceans, and these have been mapped from space. They are the lighter blue areas you can see on Google Maps.

However, not all submerged features qualify as lost continents. Most are made of materials quite distinct from what we traditionally think of as continental rock, and are instead formed by massive outpourings of magma.

A good example is Iceland which, despite being roughly the size of New Zealand’s North Island, is not considered continental in geological terms. It’s made up mainly of volcanic rocks deposited over the past 18 million years, meaning it’s relatively young in geological terms.

The only foolproof way to tell the difference between massive submarine volcanoes and lost continents is to collect rock samples from the deep ocean.

Finding the right samples is challenging, to say the least. Much of the seafloor is covered in soft, gloopy sediment that obscures the solid rock beneath.

We use a sophisticated mapping system to search for steep slopes on the seafloor, that are more likely to be free of sediment. We then send a metal rock-collecting bucket to grab samples.

The more we explore and sample the depths of the oceans, the more likely we’ll be to discover more lost continents.

The ultimate lost continent

Perhaps the best known example of a lost continent is Zealandia. While the geology of New Zealand and New Caledonia have been known for some time, it’s only recently their common heritage as part of a much larger continent (which is 95% underwater) has been accepted.

This acceptance has been the culmination of years of painstaking research, and exploration of the geology of deep oceans through sample collection and geophysical surveys.

New discoveries continue to be made.

During a 2011 expedition, we discovered two lost continental fragments more than 1,000km west of Perth.

The granite lying in the middle of the deep ocean there looked similar to what you would find around Cape Leeuwin, in Western Australia.

Other lost continents

However, not all lost continents are found hidden beneath the oceans.

Some existed only in the geological past, millions to billions of years ago, and later collided with other continents as a result of plate tectonic motions.

Folded marine sediments on the Whangaparaoa Peninsula north of Auckland, New Zealand, reflecting the formation of a convergent plate boundary in northern New Zealand in the beginning of the Miocene Period, around 23 million years ago. Adriana Dutkiewicz, Author provided

Their only modern-day remnants are small slivers of rock, usually squished up in mountain chains such as the Himalayas. One example is Greater Adria, an ancient continent now embedded in the mountain ranges across Europe.

Due to the perpetual motion of tectonic plates, it’s the fate of all continents to ultimately reconnect with another, and form a supercontinent.

But the fascinating life and death cycle of continents is the topic of another story.

Great article! I live on top of some pre-Cambrian rock (Icart gneiss), the remnants of a micro continent that split from West Africa, over 2billion years old, just a tiny portion of which now remains visible. The rest of our island of Guernsey (the northern part) is a complete suite of intrusive volcanic rock, also pre-Cambrian, that was formed during the Cadomian Orogeny. Geologists come from all over the world to collect samples….we often find their drilling holes!

LikeLike