John M. Contino explains in his American Thinker article The Contradictions of Carbon Capture. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

In May, 2022, the Biden Administration announced a $3.5 billion program to capture carbon pollution from the air, and the money has been flowing copiously. A quick search on LinkedIn for companies engaged in Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) projects will reveal dozens of companies, most of which are U.S.-based. They are well-staffed and generously funded with millions of up-front taxpayer dollars. [Note the bogus reference to plant food CO2 as carbon pollution.]

Summit Carbon Solutions does have its share of proponents — among them ethanol producers, heads of Chambers of Commerce, and politicians of all stripes from state and local governments. It’s one thing to dangle large sums of other people’s money to induce cooperation, but landowners are apparently being bludgeoned into submission with eminent domain.

The CCUS projects in the Midwestern faming states are all predicated on the continued, if not expanded, production of ethanol, because ethanol facilities present localized concentrations of CO2 that can be harnessed and disposed of more efficiently than merely sucking carbon dioxide out of the ambient atmosphere.

A Reuters article from March, 2022 reports that

The government estimates that ethanol is between 20% and 40% less carbon intensive than gasoline. But a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that ethanol is likely at least 24% more carbon intensive than gasoline, largely due to the emissions generated from growing huge quantities of corn [emphasis added].

The production of ethanol results in a net loss of energy: “Adding up the energy costs of corn production and its conversion to ethanol, 131,000 BTUs are needed to make 1 gallon of ethanol…[which] has an energy value of only 77,000 BTU.”

And let us not give short shrift to Power Density. In his 2010 book Power Hungry. The Myths of “Green” Energy and the Real Fuels of the Future, energy expert Robert Bryce compares the amount of the energy produced by various sources in terms of horsepower per acre, or wattage per square meter. An average U.S. Natural Gas Well, for example, produces 287.5 hp/acre. An Oil Stripper Well (producing 10 bbls/day) produces 148.5 hp/acre. Corn Ethanol comes in at a pathetic 0.25 hp/acre (pg. 86).

An Occam’s Razor approach to solving this problem would be

to shut down all the country’s ethanol production and

to not generate all that carbon dioxide in the first place.

Granted, the ethanol industry enjoys wide bipartisan support. But that doesn’t make it rational, or good for the country. Farmers receive substantial revenues by diverting an average of 40% of total corn yields to the production of ethanol. Why not just give that money to the farmers in exchange for them allowing 40% of their corn acreage to lie fallow? We might ask, facetiously, if we really needed all that extra corn to eat or export, why would our government prefer we burn it in our gas tanks?

Think of the savings:

♦ CO2 that would not be generated by growing and harvesting all that corn;

♦ water that would not be drained from our aquifers for irrigation;

♦ salination of our topsoil that would be abated by not applying unnecessary nitrogen fertilizers; and

♦ most obviously, the absence of the need to capture and bury carbon from ethanol plants.

An advantage of ethanol is that it reduces greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). The Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy reports that a 2021 Argonne Labs study “found that U.S. corn ethanol has 44%–52% lower GHG emissions than gasoline.” Let’s say ethanol reduces GHG by 50%. So, a tankful of gasoline with 10% ethanol yields a net GHG reduction of only 5% (50% of 10%).

Another advantage of ethanol is jobs in rural areas. The National Corn Growers Association reported that “[I]n 2019, the U.S. ethanol industry helped support nearly 349,000 direct and indirect jobs.”

Even if those advantages were sufficient to maintain or expand the ethanol industry, it sounds almost farcical to ask:

♦ “what is the cost-benefit analysis of spending billions of dollars to capture and sequester the CO2 from those corn fermentation processes, and

♦ to what extent would all that CCUS actually benefit the planet?”

When a John Kerry or a Greta Thunberg utters Climate Change Disaster words to the effect of “the sky is falling, we’re all going to die!” they would have us believe that it’s trivial to worry about boring quantitative cost-benefit ratios and returns on investment when the entire planet is facing an imminent, existential threat.

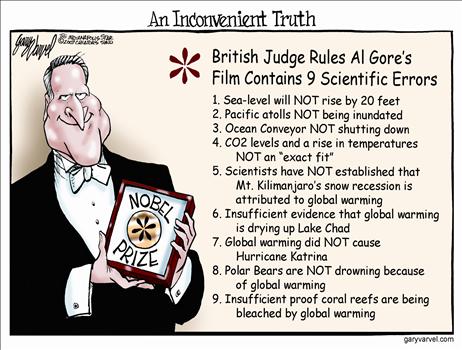

The hyperbolic language of the climate change crowd has been wearing thin ever since Al Gore’s dire predictions from 2006 have inconveniently not materialized. It’s up to us to make the left realize they’ve overplayed their hand: they cannot ride roughshod over property rights whenever it suits them, just as they cannot force us to drink Bud Light if we don’t wish to do so.

3 comments