Teresa Mull writes at American Spectator Why ‘dirty’ coal is vital to a ‘clean’ green future. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

‘Any time you have energy, you have to dig something out of the ground’

The under reported truth, however, is that coal is key to the continuation of civilization as we know it. Apart from “providing more than 36 percent of global electricity” and accounting for “nearly one-quarter of the electricity in the United States” (per the Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration), coal is necessary in the production of steel and other metals and is used in the manufacturing process of other materials city folk love, including cement. Coal is also critical in bringing about the “green, renewable” future we are told is inevitable (not to mention our first-world luxuries: smartphone batteries, fluorescent lights, computer monitors, etc.).

There are fifty critical minerals and metals in our beautiful black coal, and in the clay beneath needed to produce electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines, rechargeable batteries, and so forth. Sarma V. Pisupati, professor of energy and mineral engineering and director of the Center for Critical Minerals at Pennsylvania State University, explains that the United States imports more than 50 percent of forty-three of those elements from other countries, and twelve of those fifty minerals are 100 percent imported.

Such a strong reliance on foreign countries, especially China, which the German Marshall Fund of the United States reports “dominates global critical mineral supply chains, accounting for approximately 60 percent of worldwide production and 85 percent of processing capacity,” is “an urgent matter of national security,” says Pisupati.

Which is where Pennsylvania — and Penn State — come in.

Data from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) shows that “abandoned mine problem areas have been identified in forty-three of Pennsylvania’s sixty-seven counties.” Pennsylvania has some 5,000 miles worth of streams that have been polluted by acid mine drainage (AMD). In my own backyard (in Centre and Clearfield Counties), abandoned strip mines, described by our township solicitor as “lunar in nature,” are a playground for us backwoods folk. “The strippin’s” are where teenagers meet up to party under cover of steep high walls, coal refuse (or “boney”) piles and scraggly trees, side-by-side riders rip over rutted roads in packs each weekend and hillbillies sight-in their hunting rifles.

Yet in recent years, these “legacy coal mines,” as Pisupati calls them, have been garnering attention. Not because environmental agencies have seen the light about how important coal is, the strides the industry has made to purify the process, or because they’ve realized that re-mining is sometimes the only way to get to underground water discharges and address them, but because coal and its byproducts are a source of the critical elements necessary for a “greener” future.

“Because the old [pre-1977] coal mines were not under the new regulations, they were left abandoned, and there is a lot of water flowing through those old mines which gets oxidized, and there is a lot of acid coming out of that,” Pisupati says. “That acid actually brings out the rare earth elements and critical elements from the mines, so nature is doing some of this extraction for us. It could be viewed as a blessing in disguise, because right now we are importing these critical minerals from elsewhere.

“Acid mine drainage is flowing through those old mines and polluting our streams, so if we treat them to get these elements out, we’re actually doing a favor, and taxpayers don’t have to pay to clean these waters up if we generate money off of [the pollution]. There is work to be done, but it can be achieved so we can reduce our imports, we can make these materials right here, and we can clean up our environment.”

“Waste” produced from extracting and burning coal is increasingly becoming a misnomer. That “boney,” comprised of low-quality, “junk” coal mounded together with shale, clay, and other materials discarded during the mining process, for instance, is strewn in mountains, or “spoil piles,” throughout the region, “and the fly ash associated with coal-fired power plants are a potential source of critical minerals,” reports Penn State.

At one time, this low-quality coal and boney had no use and was piled up along old mines. Mountains of it literally surround my hometown. But now boney can be used in cogeneration (“cogen”) plants to generate electricity. According to Arnold, cogen plants “use fluidized bed combustors that operate at a lower temperature to capture all the sulfur.”

So if mining coal has the effect of unearthing the rare earth elements we so desperately need to combat “climate change,” and we need coal to make the cement and steel necessary to erect solar panels and wind turbines, and re-mining old abandoned mines offers the opportunity to extract even more rare earth elements while also cleaning up badly polluted lands and waters — the government should be handing out mining permits liberally, right?

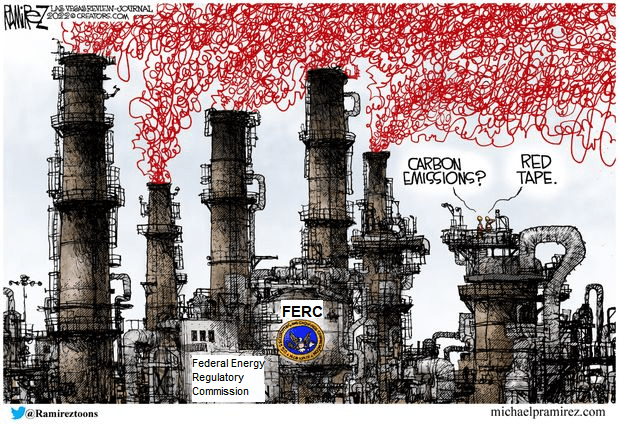

“Getting remining permits is not easy,” Pisupati says.

Not only is obtaining a permit an expensive, onerous challenge, but one of the area’s few remaining coal operators likens getting a mining permit to “a criminal sentence.” It used to be that DEP inspectors would work with operators, or as a former operator puts it, “They’d tell me what we needed to do, and we’d do it.” Yet as fossil fuels, and coal in particular, are increasingly demonized, the regulatory rope tightens, unfriendly administrations impose harsh mandates.

And mining coal becomes more of a complicated, extremely costly burden

than the prosperity-generating industry that

helped the US win back-to-back world wars.

“You can’t get anything done with DEP breathing down your neck,” one coal operator tells me. “When you do get it done, it costs four times what it should and takes four times as long. And while green energy doesn’t work, and gets subsidized, we can’t survive without coal — and coal gets taxed like crazy!”

To mine coal, you see, you must first get that permit, which can take months, if not years. The engineering required to apply for the permit could run you in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, before you’ve dug so much as a shovel full of dirt.

Next, you invest millions in heavy equipment (a new Caterpillar 992 loader runs about $1.8 million — you’ll need a couple at each job site), fuel, wages, etc. You have payments on those machines and payroll to meet, so you hope your permit gets issued quickly!

Then the coal operator must post a performance bond, carefully calculated on each cubic yard of dirt he moves, combined with the prevailing price of diesel fuel. After the operator has removed the coal, but before he backfills, he must purchase and add hundreds of tons of limestone per acre to offset the possibility that he has exposed acidic rock that could affect nearby water quality. Meanwhile, his every move is scrutinized, and he is frequently fined by an overzealous career bureaucrat.

Then, if you happen to “touch” water associated with an old mine that predates the 1977 regulations, says Rachel Gleason, executive director of the Pennsylvania Coal Alliance, “You’re responsible for treating it for the rest of its life.”

“Meanwhile,” as an operator remarks, “it’s been making a mess for 100 years.”

Gleason points out that all active coal operations in Pennsylvania are fully bonded to the cost for DEP to reclaim them, to the tune of more than $1 billion. Despite the operators putting up — and risking — so much of their own fortunes, ESG initiatives inhibiting would-be operators’ abilities to get bank loans, and the fact that operators must have a proven track record to be permitted at all, there is “definitely a lot of regulatory uncertainty” that makes it “more difficult to mine, more expensive, and the [regulations] are constantly changing.

“When efforts to shut down industry outright aren’t accomplished,

they try to kill the industry with the strike of a thousand swords.”

“If you take a step forward,” an operator tells me, “the inspectors just want to push you a step back.”

Pisupati acknowledges there are “some gaps still in knowing how much we have, what we have, and where we have [it],” and that more exploration is needed to find the highest concentrations of critical elements. He says we “definitely need a project like the Manhattan Project to get out of this import-reliance situation.”

We also need to raise awareness to “every walk of life that they are using these rare earth elements in their daily life and to educate them about their importance and dependency [and how extracting them] can revitalize the entire region that is affected by abandoned coal mines,” Pisupati adds.

As for awareness, one coal operator offers this as a starting point: “Any time you have energy, you have to dig something out of the ground,” he says. “But you never see a billboard with a windmill up top and a coal mine underneath saying, ‘We’re getting our rare earths out of here for this windmill!’”

not to mention our first-world luxuries: smartphone batteries, fluorescent lights, computer monitors, etc.

Forget the fluorescent lights…

UK to Ban T5 and T8 Fluorescent Tubes in 2023

https://www.lightrevive.co.uk/uk-to-ban-t5-and-t8-fluorescent-tubes-in-2023-what-you-need-to-know/

LikeLike