Those promoting hydrogen as a substitute for carbon fuels are blind to the physical and economic facts, as well as miscontruing CO2 as some kind of demon gas boiling the planet. Thus their crusade is absurd, exorbitant and pointless.

Hydrogen Replacing Carbon Fuels Is Absurd

The absurdity is explained by Sabine Hossenfelder in the video below: Hydrogen Won’t Save Us. Here’s Why. For those who prefer reading, I provide a transcript in italics with my bolds and added images.

Today I want to talk about something light. Hydrogen. Hydrogen is one of the currently most popular alternatives to fossil fuel in transport. Many companies and nations have put money into it.

In 2021, the number of hydrogen-fueled passenger cars bought in the UK was 12. Does that sound like a booming business? Not exactly. Indeed, a report from the British Science and Technology Committee that just appeared last month warned that “we do not believe that [hydrogen] will be the panacea to our problems that might sometimes be inferred from the hopes placed on it”.

Ouch. So what’s the deal with hydrogen? Hope or hype? That’s what we’ll talk about today.

Hydrogen Basics

Hydrogen is the first element of the periodic table. If you mix it with oxygen and put fire to the mixture you get water. This reaction releases energy, so if you do it under controlled conditions, you can drive a motor or turbine with it. The only exhaust you get is pure water, no carbon dioxide, no nitrogen oxides, no particulates, no radioactive waste, no chopped-up birds. It’s really difficult to complain about pure water.

But let’s not give up that easily, certainly we can find something to complain about. For example, hydrogen is a gas that, at normal atmospheric pressure and temperature, takes up a lot of volume, and it’s somewhat impractical to drag a zeppelin behind your car. That’s why to store and transport hydrogen, one compresses it by putting it under a lot of pressure. Typically, that’s something like 700 bar, or about 700 times atmospheric pressure.

At that pressure, the energy that one gets out of one litre of hydrogen

is one sixth of the energy one gets out of one litre of gasoline.

This means if you power a car with hydrogen, one needs more litres of hydrogen than one needs litres of gasoline to cover the same distance. But litres are a measure of volume. The amount of energy you get out of hydrogen per mass is about twice as high as what you get from gasoline. Then again, since the hydrogen must be kept under high pressure hydrogen tanks tend to be heavy compared to gasoline tanks. When everything is said and done, hydrogen-powered cars end up being somewhat heavier than gasoline-powered ones, but it’s not such a big difference.

Okay, but how do you get the energy out of the hydrogen? The technology for this isn’t new, it’s been around for more than 200 years. The first hydrogen fuel cell was developed by William Grove in 1839 but it was only in the 1960s that two engineers at General Electric proposed a smart way to go about it. They developed what’s now called a Proton Exchange Membrane. Those keep the hydrogen and oxygen largely separate and allow chemical reactions only at the membrane. That way it’s much easier to control the reaction which also makes the system safer.

Those hydrogen fuel cells were then further developed by NASA. One of the first uses was on the Gemini spacecraft, which was launched in the mid-1960s. They were later also used on the Apollo spacecraft that carried astronauts to the moon and for the space shuttle. The International Space Station uses hydrogen fuel cells to generate electricity and also to produce drinking water for the astronauts on board.

The Hydrogen Market

So, hydrogen fuel cells have been around for a long time, but they’ve never been particularly popular. One of the reasons has certainly been that there was simply no need for them, because fossil fuels are considerably more convenient. Unfortunately, they have side-effects, which is why companies like Hyundai and Toyota have been selling hydrogen-fuelled cars for about a decade. BMW, Ford, and other automobile giants have plans for hydrogen cars, and some governments are looking at hydrogen to power their transit systems, for example Scotland and Germany.

The UK with its measly 12 sales in 2021, I admit, is a particularly sad example. For one thing, that’s only passenger cars. They also put about 50 hydrogen-powered busses on the road. And globally the market doesn’t look quite as dire. In total, about 16 thousand hydrogen powered cars were sold in 2021, about three thousand 500 of those in the US. The total number of new cars sold in 2021 was about 67 million, so at the moment it’s about one in four thousand new cars that’s hydrogen powered. It’s a small market, but it’s an existing market.

Some plans are extremely ambitious. For example, in May last year, the European Union rolled out a strategy called REPowerEU, with the goal of replacing up to 50 billion cubic meters per year of imported Russian gas with hydrogen. This’d mean replacing almost 10 percent of the EU’s total gas consumption with hydrogen power. That’s substantial.

It’s not only Europe. Many other countries are also investing in hydrogen production facilities, that includes Japan, Canada, Egypt, China, and the United States. For example, in March last year, the company Green Hydrogen International unveiled plans to create a plant in Texas that’ll use 60 Gigawatt of electricity from solar and wind to produce 2 point 5 billion kilograms hydrogen per year. It’ll be called Hydrogen City. And Individual companies are investing in it, too. Microsoft, for example, wants to use hydrogen fuel cells as climate-friendly backup generators for their data centres. As you see, hydrogen is booming. But.

The Colors Of Hydrogen

The first “but” that might spring to your mind is: But where does the hydrogen come from? Now, hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe. Indeed, three quarters of all normal matter in the universe is hydrogen, but you normally can’t buy it in the supermarket. So where do you get it? Naturally occurring geological deposits of pure hydrogen are rare on Earth. Most of the hydrogen we have is bound, either in water or in methane. And this is where the problem begins. Because you have to break those chemical bonds to get the hydrogen and that requires energy.

Hydrogen is therefore not really a source of energy, but a storage system.

You use energy to create it in its pure form, transport it,

and then you release this energy elsewhere.

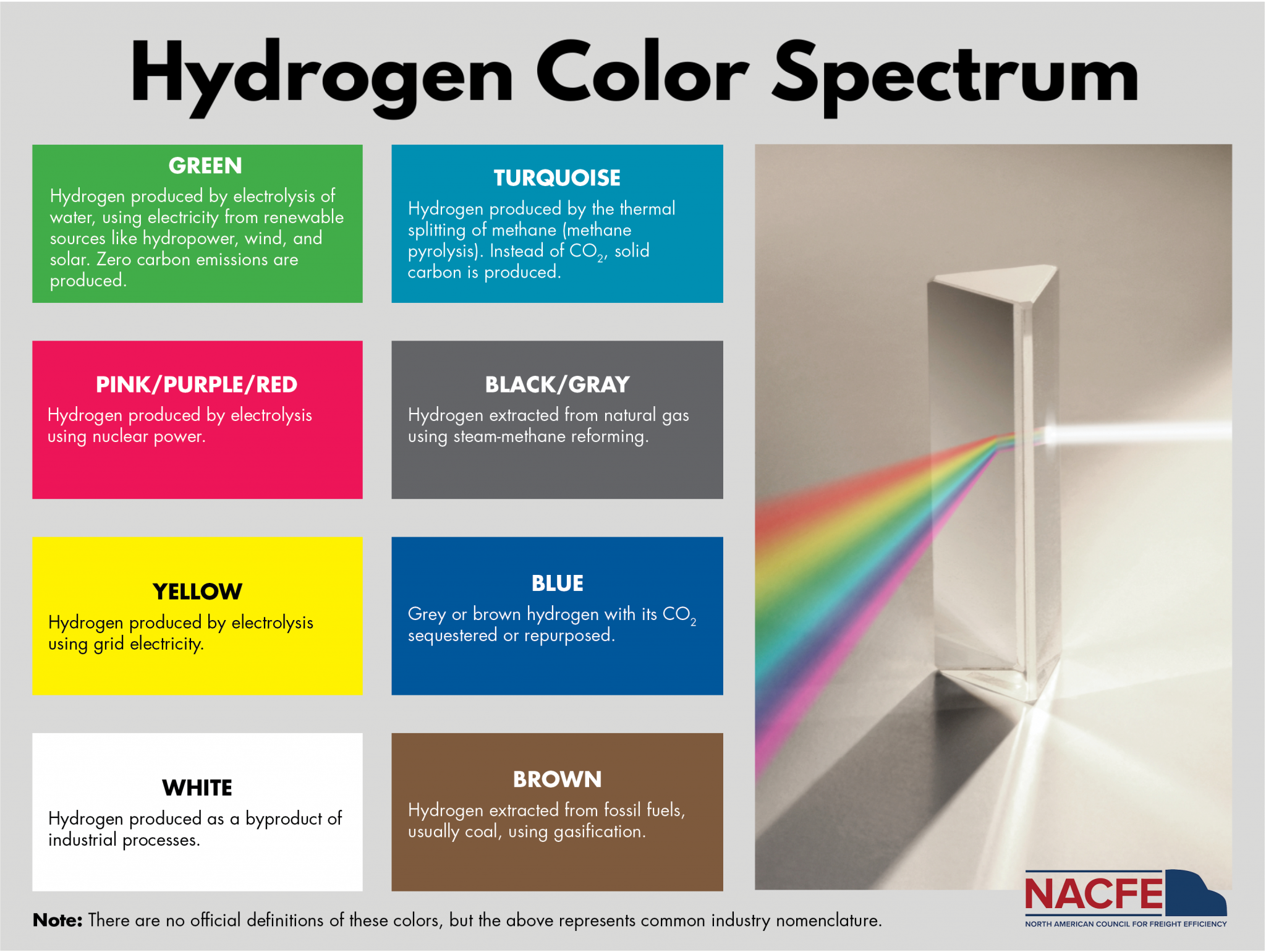

How environmentally friendly this is depends strongly on where the hydrogen comes from. To keep track of this, scientists are using a color scale. You all know this, but this is YouTube, so I have to say this anyway: The hydrogen itself has always the same color, which is transparent. This color scale is just a way of keeping track of the production method.

On this color scale, the rare, naturally occurring hydrogen is white. Hydrogen obtained from water using coal or lignite has the colors black or brown, respectively. Its production emits carbon dioxide and methane; both are greenhouse gases. Grey hydrogen is derived from methane and water; this also produces carbon dioxide and usually some of the methane escapes.

At the moment, almost all hydrogen is produced in one of those ways by using fossil fuels. According to the World Energy Council, in 2019 more than 95 percent of the hydrogen worldwide was assigned one of those colors, black, brown, or grey. This releases about 830 million tons of carbon dioxide per year. That’s 2 percent of the total global emissions and about the same as air traffic.

But there are more colors on the hydrogen rainbow. Next there is blue. Like grey hydrogen, blue hydrogen is made from methane, but the carbon dioxide is stored underground and does not escape into the atmosphere. This method is currently only used for1 percent of hydrogen production, but it could be expanded. The industry association Hydrogen Council has touted blue hydrogen as a climate-friendly initiative. It’s not entirely irrelevant, so let me mention that this council was created by the oil and gas industry. Many of its members have a financial interest in switching from natural gas to hydrogen produced from natural gas.

So maybe one shouldn’t take their argument that blue hydrogen is climate-friendly for granted. Hasn’t someone looked into this? Well, since you asked, in 2021, two American researchers calculated the amount of greenhouse gases released by grey and blue hydrogen technology. They not only took carbon dioxide into account, but also methane, which is a much more potent greenhouse gas. To make comparisons easier, the greenhouse effect from methane is usually converted to a carbon dioxide equivalent, which is the amount of carbon dioxide that would have the same effect.

They came to the conclusion that grey hydrogen has a carbon dioxide equivalent of about 550 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour and blue only slightly less, 486 grams. That’s about the same as the emissions you get from using natural gas directly to generate electricity. Part of the reason blue hydrogen performs so poorly is that not all the carbon dioxide from hydrogen production is captured and stored. Another reason is that the process of storing the carbon dioxide also requires energy and leads to carbon dioxide emissions. The authors estimate that under the most favourable conditions, it might be possible to reduce those emissions to around 200 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour by using renewable energy sources. So blue hydrogen doesn’t help much with climate protection.

Then there is green hydrogen, which is produced from water using renewable energy. Again that sounds good, and again, it’s not that simple. According to a calculation by researchers from Australia, greenhouse gas emissions from green hydrogen produced with solar energy are ideally about a quarter of those from grey hydrogen. Under realistic conditions, however, they find that emissions are comparable, particularly due to fluctuations in solar radiation that make hydrogen production inefficient. There is neither data nor any study for hydrogen production from wind but you expect this method to suffer even more from fluctuations because wind is far less reliable than sunlight.

And since these methods are inefficient, they are also expensive. Indeed, producing hydrogen with solar and wind is pretty much the most expensive way you can do it, according to a review in 2019. Now maybe those costs will go down a bit as the technology improves. But seeing that the biggest problem is that energy input fluctuates I doubt it’ll become economically competitive with the “dirty” hydrogen. This problem can be fixed by using nuclear power to generate hydrogen which has been assigned the colors pink and purple. A few projects for this are underway but it’s early days and nuclear power isn’t exactly popular.

OK, so we have seen that it isn’t all that clear whether hydrogen is climate friendly, and also, it’sexpensive. And this is only the production cost. It doesn’t include the entire infrastructure that’d be necessary to fuel a fleet of hydrogen cars. Remember you have to keep the stuff at several hundred bars and you can’t just use a normal gas station for that.

Water Supply

Let’s move on to the next problem that might come to your mind: where do we get the water from? From a distance, the world has no shortage of water, but freshwater can be scarce in certain regions of the planet. According to estimates from researchers at the University of Delaware, however, water supply issues probably won’t stand in the way of a hydrogen economy. They looked at a scenario in which we replace 18 percent of fossil fuels with hydrogen, and found that this would require about 2 percent of the amount of freshwater that’s currently used for irrigation.

Watch out, this figure has a logarithmic scale. You also see on this figure that using fossil fuels requires freshwater too, for cooling, mining, hydraulic fracturing, and refining, and it’s currently actually more than the projection for hydrogen. That’s 2 percent on the global average, but in some regions the fraction can be higher. For example, estimates for Australia are that you’d need about 4% of the water amount used for irrigation. So that seems a manageable amount, but it’s something to take into account if you want to make this work.

The Cold Start Problem

Another problem with water is that it can freeze. This is why you shouldn’t leave the beer in the car in the winter. And it’s also why hydrogen fuel cells like it warm. If the temperature drops more than a few degrees below zero, the water that the fuel cells create at start will freeze immediately, which swiftly degrades the membranes and tubes. It’s known as the “Cold Start” problem of hydrogen fuel cell. And, no, you can’t just pour antifreeze into it, remember the water is created in the fuel cell. So, you’ll either have to stay in California or keep your car warm. The solution that manufacturers pursue at the moment is pre-heating systems.

Rare Metal Shortages

But the biggest problem for a hydrogen economy may be making those proton exchange membranes to begin with. It’s not because it’s so difficult, but because they’re made of platinum and iridium. Platinum you may have heard of, it’s an expensive noble metal that’s also used for jewellery. The reason it’s expensive is that it’s rare. Iridium is also a noble metal. It’s so rare that most people have never heard of it. Both of those metals are difficult to replace with anything else in the hydrogen fuel cells.

That’s a problem because it means that the entire hydrogen economy hinges on the availability of those two metals. There’s only so much of those in the world and they are only in very specific geological formations. Almost all the platinum and iridium supply comes from only three countries: South Africa, Russia, and Zimbabwe, and colonies have gone out of fashion recently. China, which has invested heavily in hydrogen technology is already feeling the consequences.

And we’ve only just barely begun with building the hydrogen economy. This issue has been highlighted recently in reports from various international organizations including the International Energy Agency and the World Bank. According to the business consulting group Wood Mackenzie, the increased demand for platinum might be manageable in the near future, but it looks like by 2030 demand for iridium will be several times higher than the supply. I don’t know much about trade, but I think this isn’t good.

It’s possible to make fuel cells somewhat more efficient and decrease the demand for those rare metals. But this situation isn’t going to change and iridium isn’t going to move to the US even if you ask it really nicely.

Have we learned nothing from the Hindenburg Disaster?

Hydrogen Embrittlement

One final problem that’s worth mentioning is that hydrogen is just nasty to deal with. Hydrogen is the smallest molecule. If you squeeze it into a tank, it’ll creep into the walls of the tank. That destroys the chemical structure of the material and makes it brittle. It’s called “hydrogen embrittlement”. For this reason, hydrogen tanks must be thick and specially coated, which makes them both heavy and expensive. Like the cold start problem, this one’s basic chemistry and isn’t going to go away. And the need to keep the hydrogen under pressure makes the stuff inconvenient to handle. The city of Wiesbaden in Germany, for example, recently retired its six new hydrogen powered buses because the filling station broke down, sinking a few million Euro.

Summary

In summary, hydrogen production at the moment has a high carbon footprint because it’s almost exclusively done using fossil fuels. Reducing the carbon footprint of hydrogen production seems difficult according to estimates, but at the moment there’s basically no real-world data. Hydrogen produced by wind and solar will almost certainly not be economically competitive with that derived from fossil fuels but using nuclear power might be an option. Building infrastructure for a transport-system based on hydrogen would eat up a lot of money. It seems that rare metal supply for hydrogen fuel cells is going to become a problem in the near future which won’t help making the technology affordable. Keeping hydrogen stored and under pressure adds to the cost and makes those systems heavy which isn’t great for transport. And finally, hydrogen-powered cars don’t like cold temperatures.

So. Well, it seems to me that the British Science and Technology committee is right. A hydrogen economy isn’t a panacea for climate change. Indeed, the French have a similar committee that likewise concluded “l’hydrogène n’est pas une solution miracle”. I must admit that I was considerably more upbeat about hydrogen before I started working on this video. How about you? Did you learn something new? Did you change your mind? Let us know in the comments.

There is also a quiz to test your comprehension of key points after watchiing or reading Is Hydrogen the Next Big Energy Source?

Summation: The Hydrogen Crusade is absurd because hydrogen

is not an energy source, but a storage system, and

natural properties and scarcities will not be suspended

for the sake of human ambitions.

Hydrogen Replacing Carbon Fuels Is Exorbitant

Frank Lasee addresses the economics of Hydrogen fuel production and distribution in his Real Energy article Hydrogen Hubs: Without Huge Subsidies the Math Doesn’t Work. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images

The White House has awarded $7 billion dollars of tax money for the first seven U.S. hydrogen hubs. They say it will leverage $43 billion in private money. Yet, the rules only require a 50/50 match. We are far more likely to see a $7 billion private money match. Why put more of your own money at risk than you have to?

It is risky because green hydrogen costs at least five times more to produce than the methane reforming method, which makes 95% today. That is $5 versus $1. All of the regional hydrogen infrastructure will need to be built, and the future hydrogen demand will need to be created and incentivized. Because green hydrogen still costs more. Even with upfront and downstream aggressive subsidies.

Because it is tax money we don’t have, it is added to our unprecedented $33 trillion dollar national debt. We are at an inflection point where interest payments are more than our national defense budget. Debt interest is projected to be more than a trillion dollars by the end of the decade. And the Rich Men North of Richmond just keep spending.

It costs $5 or more to produce green hydrogen through hydrolysis. Which takes super heating, electrocuting, super chilling, and compression. Then additional costs for storage and transportation before it is used somewhere.

And it needs 53 times more water than hydrogen made. Not a good idea in dry California, which is awarded $1 billion in giveaway hub money.

All of this takes lots of full-time energy. Not the part-time unpredictable electricity wind and solar make. Let’s not talk about our stressed national grid with regular blackout and shortage notices. Or the fact that 60% of the electricity made for the grid comes from coal and natural gas.

Paying for full-time and part-time generation, and thousands of miles

of transmission wires will at least triple our electric rates in no time.

This hurts the poor the most, because they use the biggest amount of their budgets on energy costs. Stressing their lives, hurting their ability to live independently. All of this, while Biden and the democrats blather about climate justice and social justice.

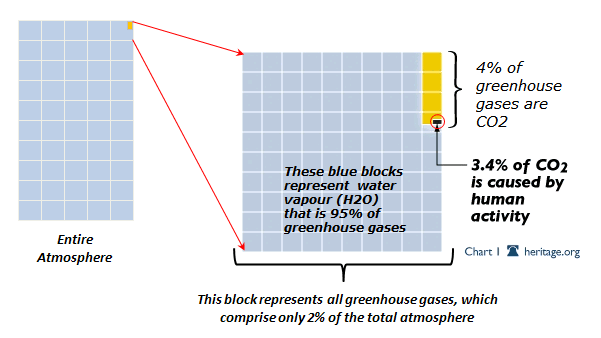

We are doing all this subsidizing to stop

the addition of the super plant food CO2.

That is greening our earth, regrowing forests the size of France, and increasing crop yields and harvests around the world. To supposedly stop the warming of the planet that started naturally in 1850. As if we can.

The Rich Men North of Richmond are going to waste 100s of billions on green taxpayer giveaways on top of the $9.5 billion upfront hydrogen give away.

Throwing money at a climate emergency that doesn’t really exist is part of Bidenomics. Fueling inflation by spending money we don’t have, fueling high interest rates by fueling inflation. Making it difficult and expensive to harvest the fossil fuels that supply 80% of our energy. And sending 100s of billions, if not trillions, to our main rival and biggest threat, totalitarian, communist China is the Biden way.

Wind, solar, batteries, and soon EVs made in China with

forced labor, low-cost coal electricity and little environmental protections.

China burns more than half of the world’s 8.5 billion tons of coal used annually and is building hundreds of coal plants that last 50 to 75 years. I am sure they intend to use them for a few decades or 75 years.

For those that think CO2 emissions are important, China emits more than the U.S. and all the other industrialized nations combined. Including India, which is no slouch when it comes to using coal for power, getting even a larger percentage of their energy from coal than China.

We need to end this crazy fantasy of a centrally forced transition to hydrogen, wind, solar, batteries and electric vehicles. It isn’t working and is making everything more costly. Because energy is in everything we eat, buy, use, consume, even Netflix and AI.

Summation: The Hydrogen Crusade is exorbitant because

the costs are unbearable and unsustainable,

a ruinous drain on our energy resources.

Hydrogen Replacing Carbon Fuels Is Pointless

The greatest insanity is that all of this crusade is unecessary. The delusional premise of the Hossenfelder video is that we and the planet need saving from CO2. When in fact throughout history, atmospheric CO2 changes lag Temperature changes on all time scales; from last month’s observations to ice cores showing climate changes over thousands and millions of years. Nothing in nature can be the cause of an effect if it occurs afterward. A thorough debate on this issue occured recently at Dr. Judith Curry’s website Climate Etc. on the topic Causality and climate. My synopsis is below.

I learned alot from a recent extended discussion at Climate Etc. Causality and Climate responding to a paper Demetris Koutsoyiannis et al. (2023) On Hens, Eggs, Temperatures and CO2: Causal Links in Earth’s Atmosphere. My previous post on this paper was:

I recommend the discussion thread at climate etc. (on going) as a tutorial for the competing paradigms regarding the CO2 cycle. I gained clarity from the lead author (a frequent and constructive participant) as well others on the core misunderstanding that has plagued such discussions for decades. Some comments are below in italics with my bolds.

First, note that the paper had a narrowly defined scope: to demonstrate from available data that changes in atmospheric CO2 lag rather than lead temperature changes. Because the authors recognized that this finding is contrary to IPCC consensus climate science, appendices were supplied to counter the expected objections crediting human CO2 emissions from hydrocarbons as the main, or sole source of rising CO2 since the Little Ice Age (LIA). As Koutsoyiannis explained in a summary comment near the end:

Demetris Koutsoyiannis September 29, 2023 at 4:54 pm

I think I have rebutted all the different critiques ON MY PAPERS. I am not going to reply to critiques on any other issues related to the issue of climate. Please make your critiques SPECIFIC, by quoting phrases in my papers that you think are incorrect. And before it, please read the papers.

For example you say:

> And that would be the cause of the CO2 increase in the atmosphere?

If you read the paper you will see that we write (p. 17): *What is the cause of the modern increase in temperature? Apparently, this question is much more difficult to reply to, as we can no longer attribute everything to any single agent. We do not claim to have the answer to this question, whose study is far beyond the article’s scope. Neither do we believe that mainstream climatic theory, which is focused upon human CO2 emissions as the main cause and regards everything else as feedback of the single main cause, can explain what happened on Earth for 4.5 billion years of changing climate.*

We have proposed a necessary condition for causality, which is time precedence of the cause over the effect. I hope you accept that necessary condition, am I wrong? We make our inference based on this necessary condition. Your numbers make no reference of time succession. When you find a way to test whether the direction in time is reversed, that will be great. But for now, all this looks to me an unproven conjecture. I hope you can excuse me that, being a Greek, I have to stick to Aristotelian logic.

You also say:

> While there is an elephant in the room, human emissions that released twice as much CO2 as measured in the atmosphere…

If this is the elephant, what is (copying from our paper, p. 25), *a total global increase in the respiration rate of ΔR = 31.6 Gt C/year. This rate, which is a result of natural processes, is 3.4 times greater than the CO2 emission by fossil fuel combustion (9.4 Gt C /year including cement production)*.

My Comment: The confounding issue in all this was identified as the mistaken analogy treating CO2 fluxes as though they are cash transactions between bank accounts. Within that notion, a natural source/sink must net out intakes and releases. Yet as others commented, geobiologists know that both absorption and release can be increasing or can be decreasing. The source/sinks function dynamically, not statically as assumed by the analogy.

What It Means: CO2 flows through Dynamic Reservoirs

The other puzzle piece is described by Ed Berry following his peer-reviewed paper Nature Controls the CO2 Increase II. A summary comment ties his analysis into the above discussion. Early in the thread the point was made that all CO2 sources are involved in supporting the level of atmospheric concentration at any point in time. Ed Berry made this point in this way.

He explained that when you look at the flow of carbon dioxide—”flow” meaning the carbon moving from one carbon reservoir to another, i.e., through photosynthesis, the eating of plants, and back out through respiration—a 140 ppm constant level requires a continual inflow of 40 ppm per year of carbon dioxide, because, according to the IPCC, carbon dioxide has a turnover time of 3.5 years (meaning carbon dioxide molecules stay in the atmosphere for about 3 1/2 years). 140 ppm divided by 3.5 is 40 ppm CO2.

“A level of 280 ppm is twice that—80 ppm of inflow. Now, we’re saying that the inflow of human carbon dioxide is one-third of the total. Even IPCC data says, ‘No, human carbon dioxide inflow is about 5 percent to 7 percent of the total carbon dioxide inflow into the atmosphere,’” he said.

[Today’s level of nearly 420 ppm means that 120 ppm of inflow is required annually, or 120 +2 ppm if it is to increase as it has been. Where does 122 ppm of CO2 come from? Well, let’s say we can count on 6 ppm of FF CO2 (5%) and the other 116 being non-human emissions.]

Summation: The Hydrogen Crusade is pointless because

our carbon emissions do not determine either

atmospheric CO2 or the Earth’s temperatures.

5 comments