In his American Thinker article Chris J. Krisinger reports on another distortion proclaimed at COP28 World Leaders’ Terror of Climate Change. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

[During his Air Force career, Colonel Krisinger served as military advisor to the assistant secretary of state for European affairs at the Department of State while working from the NATO Policy Office. He is a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy and the Naval War College and was also a National Defense Fellow at Harvard University. ]

Playing to what amounted to a friendly home crowd at the Dubai U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP28), NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg went there to deliver a message touting a relationship between global security and climate change, while emphasizing the necessity of shifting military resources to combat global warming.

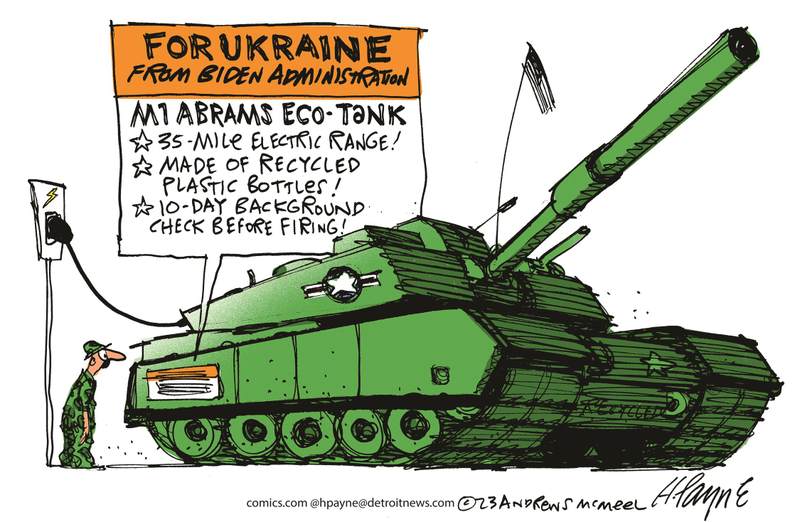

In his speech, set against a backdrop of the Ukraine war, he was adamant about the influence of climate change on international security with conflict actually undermining “our capability to combat climate change because resources that we should have used to combat climate change are spent on our protecting our security with our military forces.” He would even become apologetic about the Alliance’s reliance on fossil fuel–intensive military machinery, telling the audience, “If you look at big battle tanks and the big battleships and fighter jets, they are very advanced and great in many ways, but they’re not very environmentally friendly. They pollute a lot, so we need to get down the emissions.”

Stoltenberg’s address at COP28 comes not long after President Biden’s September declaration in Vietnam that “the only existential threat humanity faces even more frightening than a nuclear war is global warming.” Then, just two days after the October 7 attack on Israel, instead of talking about hostages and the U.S. response, National Security Council spokesman John Kirby went in front of TV cameras defending that statement: “the president believes wholeheartedly that climate change is an existential threat to all of human life on the planet.”

But do world events — present or past — justify such inordinate interest by political leaders in climate change shaping the global security environment who go so far as to deem it an “existential threat to humankind”? Does the still uncertain and arguable science of climate change cross a threshold to influence, even justify, Alliance or national decision-making to link defense and security policy, actions, and investments? World events reminds us it does not.

The current century’s major conflicts — Iraq, Afghanistan, Assad’s Syria, Ethiopia’s Tigray war, Yemen’s and South Sudan’s civil wars, and more recently Ukraine and Israel’s war against Hamas — have no compelling environmental or climatological links, just as all other international conflicts in the post-WWII era did not. ISIL, which once controlled large swaths of some of the planet’s most inhospitable desert areas in Syria and Iraq, professed no regard for “climate change” in its worldview, nor has Hamas or Hezbollah today, both of which also inhabit arid, hot desert lands.

Arguably, no conflict in human history, modern or otherwise, has a causal

(or effectual) relationship with climate change, despite the planet

undergoing periods of both warming and cooling.

Today’s foremost security threats — e.g., great power competition, cyber-attacks, piracy, weapons of mass destruction, terrorism, nuclear proliferation, financial crises, dictatorships, nationalism, drug-trafficking, insurgencies, revolutions, Iran, North Korea, etc. — all continue to fester. None can be persuasively linked to climate change, even as a worsening effect. Further, climate change does not appear to drive the agendas or motives of global antagonists like Putin, Xi, Al-Shabaab, the Taliban, Kim, Khomeini, Assad, al-Qaeda, cartels, Hezb’allah, Hamas, the Houthis, Boko Haram, or others.

Instead, consider that environmental factors rarely incite

conflict within or between nations.

In fact, the opposite — international cooperation — is the more likely outcome in concert with the human race’s innate ability to adapt to its environment. The climate-security link Stoltenberg wants us to accept can be greatly overstated and instead aimed to serve political agendas and economics more than addressing real security threats. What climate advocates further ignore or overlook is the slow, gradual process over years, decades, even centuries by which environmental phenomena occur, while ignoring empirical evidence of the pace, causes, and drivers of current events. Climate change is not the catalyst determining whether conflict occurs or its severity.

Of more practical importance is that, should a military response be required,

military forces must be prepared to operate and prevail in

whatever weather extremes are encountered at that moment.

Their equipment and resources must best perform their military function, regardless of environmental sensibilities. In one telling example, if U.S. or NATO forces had been required to operate in Russia in 2012 along similar routes as the Wehrmacht in 1941 and Napoleon in 1812, they would have encountered worse cold and weather than in either of those campaigns, so infamously ravaged by winter.

In fact, Russia endured its harshest winter in over 70 years and had not experienced such a long cold spell since 1938, with temperatures 10–15 degrees below seasonal norms nationwide. Like Russia, China’s 2012 winter temperatures were the lowest in almost three decades, cold enough to freeze coastal waters and trap hundreds of ships in ice. Even today, had the COP28 conference been held at a European location, Stoltenberg may have become snowbound while traveling, with more of the continent under snow cover in December’s first week than in any year for more than a decade.

A Lufthansa aircraft at the snow-covered Munich airport on Saturday, Dec. 2, 2023. Photograph: Karl-Josef Hildenbrand/AP

A NATO alliance currently facing epic regional challenges cannot lose focus on core security and defense priorities or its profound grasp of the true origins, causes, and motives for human conflict. Both military and political leaders cannot be distracted from true security threats — i.e., antagonists and competitors willfully and purposefully directing adversarial, often military, actions against a member nation with malicious intent — or not be prepared to operate and prevail in whatever weather or climatic conditions are encountered at that time.

With such clarity — absent the narrative, politics, uncertainty, and rhetoric of climate change — NATO, its member nations, and their leaders can then best direct its substantial enterprise towards those more numerous, serious, and pressing security threats facing the Alliance.

Background Food, Conflict and Climate

From data versus models department, a recent study contradicts claims linking human conflict to climate change by means of food shortages. From Dartmouth College March 1, 2018 comes Food Abundance and Violent Conflict in Africa. by Ore Koren. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2018; Synopsis is from Science Daily (here) with my bolds.

Food abundance driving conflict in Africa, not food scarcity

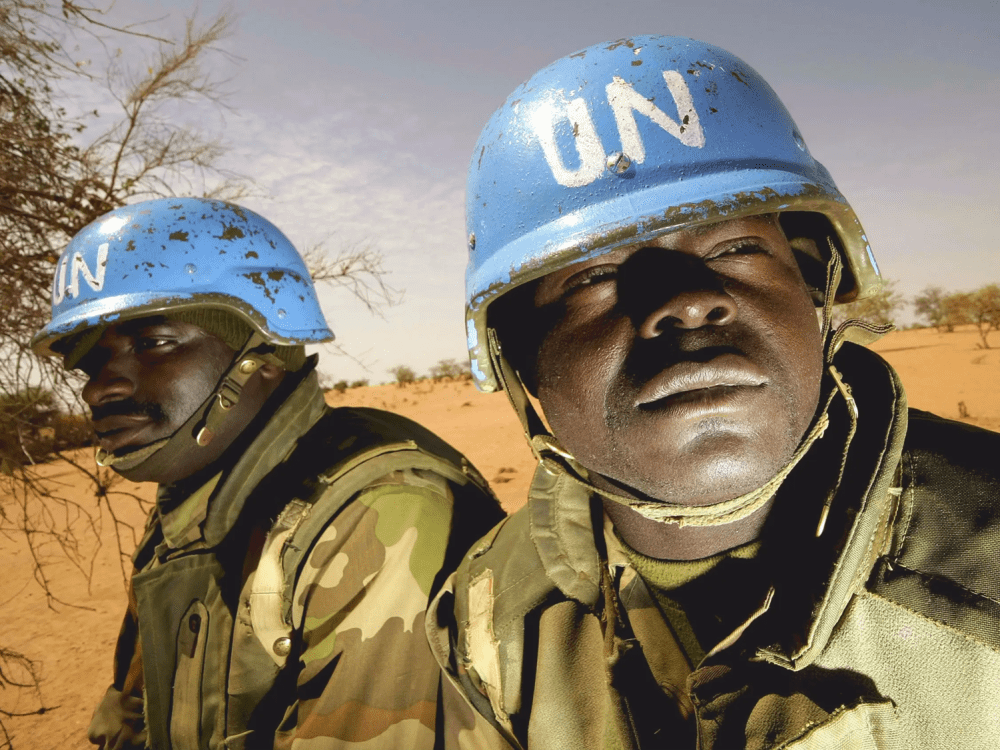

The study refutes the notion that climate change will increase the frequency of civil war in Africa as a result of food scarcity triggered by rising temperatures and drought. Most troops in Africa are unable to sustain themselves due to limited access to logistics and state support, and must live off locally sourced food. The findings reveal that the actors are often drawn to areas with abundant food resources, whereby, they aim to exert control over such resources.

To examine how the availability of food may have affected armed conflict in Africa, the study relies on PRIO-Grid data from over 10,600 grid cells in Africa from 1998 to 2008, new agricultural yields data from EarthStat and Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset, which documents incidents of political violence, including those with and without casualties. The data was used to estimate how annual local wheat and maize yields (two staple crops) at a local village/town level may have affected the frequency of conflict. To capture only the effects of agricultural productivity on conflict rather than the opposite, the analysis incorporates the role of droughts using the Standardized Precipitation Index, which aggregates monthly precipitation by cell year.

The study identifies four categories in which conflicts may arise over food resources in Africa, which reflect the interests and motivations of the respective group:

- State and military forces that do not receive regular support from the state are likely to gravitate towards areas, where food resources are abundant in order to feed themselves.

- Rebel groups and non-state actors opposing the government may be drawn to food rich areas, where they can exploit the resources for profit.

- Self-defense militias and civil defense forces representing agricultural communities in rural regions, may protect their communities against raiders and expand their control into other areas with arable land and food resources.

- Militias representing pastoralists communities live in mainly arid regions and are highly mobile, following their cattle or other livestock, rather than relying on crops. To replenish herds or obtain food crops, they may raid other agriculturalist communities.

These actors may resort to violence to seek access to food, as the communities that they represent may not have enough food resources or the economic means to purchase livestock or drought-resistant seeds. Although droughts can lead to violence, such as in urban areas; this was found not to be the case for rural areas, where the majority of armed conflicts occurred where food crops were abundant.

Food scarcity can actually have a pacifying effect.“Examining food availability and the competition over such resources, especially where food is abundant, is essential to understanding the frequency of civil war in Africa,” says Ore Koren, a U.S. foreign policy and international security fellow at Dartmouth College and Ph.D. candidate in political science at the University of Minnesota. “Understanding how climate change will affect food productivity and access is vital; yet, predictions of how drought may affect conflict may be overstated in Africa and do not get to the root of the problem. Instead, we should focus on reducing inequality and improving local infrastructure, alongside traditional conflict resolution and peace building initiatives,” explains Koren.

Summary:

In Africa, food abundance may be driving violent conflict rather than food scarcity, according to a new study. The study refutes the notion that climate change will increase the frequency of civil war in Africa as a result of food scarcity triggered by rising temperatures and drought.

Reading the study itself shows considerable rigor in sorting out dependent and independent variables. It is certain that armed conflicts destroy food resources, while it is claimed that food shortages from climate events like drought cause the conflicts in the first place. From Koren:

Moreover, in addition to illustrating the validity of this mechanism by the process of elimination—that is, by empirically accounting for a variety of alternative mechanisms— figure 2 further highlights the interactions between economic inequality, food resources, and conflict. Here, nonparametric regression plots—which do not enforce a modeling structure on the data and hence provide a more flexible method of visualizing relationships between different factors—show the correlations of local yields and conflict with respect to economic development as approximated using nighttime light levels. As shown, conflict occurs more frequently in cells with more crop productivity, but relatively low levels of economic development, where—based on anecdotal evidence at least—limitations on food access are more likely (Roncoli, Ingram, and Kirshen 2001).

In Addition

https://rclutz.wordpress.com/2017/07/14/updated-climates-dont-start-wars-people-do/

NATO Chief is poorly informed, or misinformed.

USGS Factsheet: The Sun and Climate (2000)

Solar activity was generally low (14C production high) during the period A.D. 1300 to 1900, with two distinct lows, the Spörer and Maunder Minima (fig. 3). It has only been in the 20th century that solar activity has increased (14C production decreased) to levels that occurred during the Medieval Maximum (fig. 3).

— https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs-0095-00/fs-0095-00.pdf

LikeLike