A recent question was posed on Quora: Say there are merely 15 variables involved in predicting global climate change. Assume climatologists have mastered each variable to a near perfect accuracy of 95%. How accurate would a climate model built on this simplified system be? Keith Minor has a PhD in organic chemistry, PhD in Geology, and PhD in Geology & Paleontology from The University of Texas at Austin. He responded with the text posted below in italics with my bolds and added images.

I like the answers to this question, and Matthew stole my thunder on the climate models not being statistical models. If we take the question and it’s assumptions at face value, one unsolvable overriding problem, and a limit to developing an accurate climate model that is rarely ever addressed, is the sampling issue. Knowing 15 parameters to 99+% accuracy won’t solve this problem.

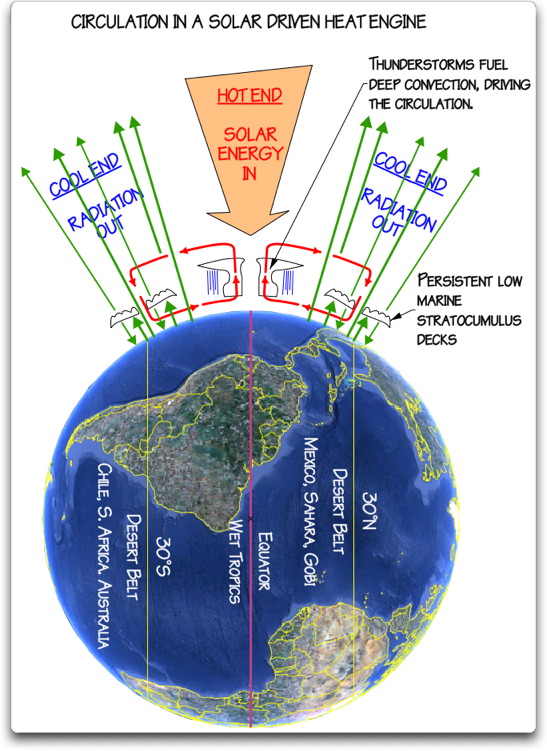

The modeling of the atmosphere is a boundary condition problem. No, I’m not talking about frontal boundaries. Thermodynamic systems are boundary condition problems, meaning that the evolution of a thermodynamic system is dependent not only on the conditions at t > 0 (is the system under adiabatic conditions, isothermal conditions, do these conditions change during the process, etc.?), but also on the initial conditions at t = 0 (sec, whatever). Knowing almost nothing about what even a fraction of a fraction of the molecules in the atmosphere are doing at t = 0 or at t > 0 is a huge problem to accurately predicting what the atmosphere will do in the near or far future. [See footnote at end on this issue.]

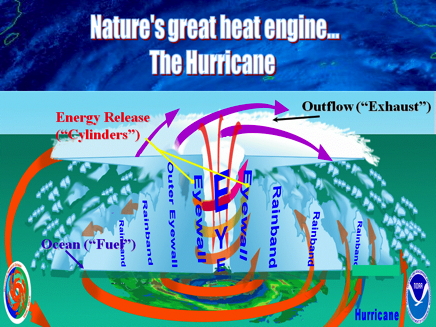

Edward Lorenz attempted to model the thermodynamic behavior of the atmosphere by using models that took into account twelve variables (instead of fifteen as posed by the questioner), and found (not surprisingly) that there was a large variability in the models. Seemingly inconsequential perturbations would lead to drastically different results, which diverged (euphemism for “got even worse”) the longer out in time the models were run (they still do). This presumably is the origin of Lorenz’s phrase “the butterfly effect”. He probably meant it to be taken more as an instructive hypothetical rather than a literal effect, as it is too often taken today. He was merely illustrating the sensitivity of the system to the values of the parameters, and not equating it to the probability of outcomes, chaos theory, etc., which is how the term has come to be known. This divergence over time is bad for climate models, which try to predict the climate decades from now. Just look at the divergence of hurricane “spaghetti” models, which operate on a multiple-week scale.

The sources of variability include:

♦ the inability of the models to handle water (the most important greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, not CO2) and processes related to it;

♦ e.g., models still can’t handle the formation and non-formation of clouds;

♦ the non-linearity of thermodynamic properties of matter (which seem to be an afterthought, especially in popular discussions regarding the roles that CO2 plays in the atmosphere and biosphere), and

♦ the always-present sampling problem.

While in theory it is possible to know what a statistically significant number of the air and water molecules are doing at any point in time (that would be a lot of atoms and molecules!), a statistically significant sample of air molecules is certainly not being sampled by releasing balloons twice a day from 90 some odd weather stations in the US and territories, plus the data from commercial aircraft, plus all of the weather data from around the World. Doubling this number wouldn’t help, i.e wouldn’t make any difference. Though there are some blind spots, such as northeast Texas that might benefit from having a radar in the area. So you have to weigh the cost of sampling more of the atmosphere versus the 0% increase in forecasting accuracy (within experimental error) that you would get by doing so.

I’ll go out on a limb and say that the NWS (National Weather Service) is actually doing pretty good job in their 5-day forecasts with the current data and technologies that they have (e.g., S-band radar), and the local meteorologists use their years of experience and judgment to refine the forecasts to their viewing areas. The old joke is that a meteorologist’s job is the one job where you can be wrong more than half the time and still keep your job, but everyone knows that they go to work most, if not all, days with one hand tied behind their back, and sometimes two! The forecasts are not that far off on average, and so meteorologists get my unconditional respect.

In spite of these daunting challenges, there are certainly a number of areas in weather forecasting that can be improved by increased sampling, especially on a local scale. For example, for severe weather outbreaks, the CASA project is being implemented using multiple, shorter range radars that can get multiple scan directions on nearby severe-warned cells simultaneously. This resolves the problem caused by the curvature of the Earth as well as other problems associated with detecting storm-scale features tens or hundreds of miles away from the radar. So high winds, hail, and tornadoes are weather events where increasing the local sampling density/rate might help improve both the models and forecasts.

Prof. Wurman at OU has been doing this for decades with his pioneering work with mobile radar (the so-called “DOW’s”). Let’s not leave out the other researchers who have also been doing this for decades. The strategy of collecting data on a storm from multiple directions at short distances, coupled with supercomputer capabilities, has been paying off for a number of years. As a recent example, Prof. Orf at UW Madison, with his simulation of the May 24th, 2011 El Reno, OK tornado (you’ve probably seen it on the Internet), has shed light on some of the “black box” aspects to how tornadoes form. [Video below is Leigh Orf 1.5 min segment for 2018 Blue Waters Symposium plenary session. This segment summarizes, in 90 seconds, some of the team’s accomplishments on the Blue Waters supercomputer over the past five years.]

Prof. Orf’s simulation is just that, and the resolution is around ~10 m (~33 feet), but it illustrates how increased targeted sampling can be effective in at least understanding the complex, thermodynamic processes occurring within a storm. Colleagues have argued that the small improvements in warning times in the last couple of decades are really due more to the heavy spotter presence these days rather than case studies of severe storms. That may be true. However, in test cases of the CASA system, it picked out the subtle boundaries along which the storms fired that did go unnoticed with the current network of radars. So I’m optimistic about increased targeted sampling for use in an early warning system.

These two examples bring up a related problem-too much data! As commented on by a local meteorologist at a TESSA meeting, one of the issues with CASA that will have to be resolved is how to handle/process the tremendous amounts of data that will be generated during a severe weather outbreak. This is different from a research project where you can take your data back to the “lab”. In a real-time system, such as CASA, you need to have the ability to process the volumes of data rapidly so a meteorologist can quickly make a decision and get that life-saving info to the public. This data volume issue may be less of a problem for those using the data to develop climate models.

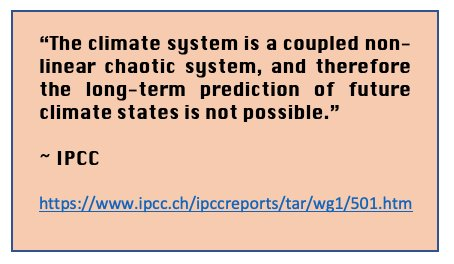

So back to the Quora question, with regard to a cost-effective (cost-effect is the operational term) climate model or models (say an ensemble model) that would “verify” say 50 years from now, the sampling issue is ever present, and likely cost-prohibitive at the level needed to make the sampling statistically significant. And will the climatologist be around in 50 years to be “hoisted with their own petard” when the climate model is proven to be wrong? The absence of accountability is the other problem with these long-range models into which many put so much faith.

But don’t stop using or trying to develop better climate models. Just be aware of what variables they include, how well they handle the parameters, and what their limitations are. How accurate would a climate model built on this simplified system [edit: of 15 well-defined variables (to 95% confidence level)] be? Not very!

My Comment

As Dr. Minor explains, powerful modern computers can process detailed observation data to simulate and forecast storm activity. There are more such tools for preparing and adapting to extreme weather events which are normal in our climate system and beyond our control. He also explains why long-range global climate models presently have major limitations for use by policymakers.

Footnote Regarding Initial Conditions Problem

What About the Double Pendulum?

Trajectories of a double pendulum

A comment by tom0mason at alerted me to the science demonstrated by the double compound pendulum, that is, a second pendulum attached to the ball of the first one. It consists entirely of two simple objects functioning as pendulums, only now each is influenced by the behavior of the other.

Lo and behold, you observe that a double pendulum in motion produces chaotic behavior. In a remarkable achievement, complex equations have been developed that can and do predict the positions of the two balls over time, so in fact the movements are not truly chaotic, but with considerable effort can be determined. The equations and descriptions are at Wikipedia Double Pendulum

Long exposure of double pendulum exhibiting chaotic motion (tracked with an LED)

But here is the kicker, as described in tomomason’s comment:

If you arrive to observe the double pendulum at an arbitrary time after the motion has started from an unknown condition (unknown height, initial force, etc) you will be very taxed mathematically to predict where in space the pendulum will move to next, on a second to second basis. Indeed it would take considerable time and many iterative calculations (preferably on a super-computer) to be able to perform this feat. And all this on a very basic system of known elementary mechanics.

2 comments