Power Density Physics Trump Energy Politics

A plethora of insane energy policy proposals are touted by clueless politicians, including the recent Democrat candidate for US President. So all talking heads need reminding of some basics of immutable energy physics. This post is in service of restoring understanding of fundamentals that cannot be waved away.The Key to Energy IQ

This brief video provides a key concept in order to think rationally about calls to change society’s energy platform. Below is a transcript from the closed captions along with some of the video images and others added.

We know what the future of American energy will look like. Solar panels, drawing limitless energy from the sun. Wind turbines harnessing the bounty of nature to power our homes and businesses. A nation effortlessly meeting all of its energy needs with minimal impact on the environment. We have the motivation, we have the technology. There’s only one problem: the physics.

We know what the future of American energy will look like. Solar panels, drawing limitless energy from the sun. Wind turbines harnessing the bounty of nature to power our homes and businesses. A nation effortlessly meeting all of its energy needs with minimal impact on the environment. We have the motivation, we have the technology. There’s only one problem: the physics.

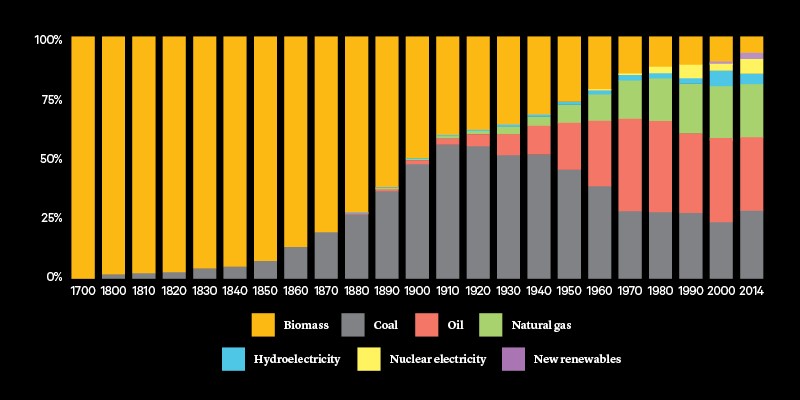

The history of America is, in many ways, the history of energy. The steam power that revolutionized travel and the shipping of goods. The coal that fueled the railroads and the industrial revolution. The petroleum that helped birth the age of the automobile. And now, if we only have the will, a new era of renewable energy.

The history of America is, in many ways, the history of energy. The steam power that revolutionized travel and the shipping of goods. The coal that fueled the railroads and the industrial revolution. The petroleum that helped birth the age of the automobile. And now, if we only have the will, a new era of renewable energy.

Except … it’s a little more complicated than that. It’s not really a matter of will, at least not primarily. There are powerful scientific and economic constraints on where we get our power from. An energy source has to be reliable; you have to know that the lights will go on when you flip the switch. An energy source needs to be affordable–because when energy is expensive…everything else gets more expensive too. And, if you want something to be society’s dominant energy source, it needs to be scalable, able to provide enough power for a whole nation.

Those are all incredibly important considerations, which is one of the reasons it’s so weird that one of the most important concepts we have for judging them … is a thing that most people have never heard of. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the exciting world of…power density.

Except … it’s a little more complicated than that. It’s not really a matter of will, at least not primarily. There are powerful scientific and economic constraints on where we get our power from. An energy source has to be reliable; you have to know that the lights will go on when you flip the switch. An energy source needs to be affordable–because when energy is expensive…everything else gets more expensive too. And, if you want something to be society’s dominant energy source, it needs to be scalable, able to provide enough power for a whole nation.

Those are all incredibly important considerations, which is one of the reasons it’s so weird that one of the most important concepts we have for judging them … is a thing that most people have never heard of. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the exciting world of…power density.

Look, no one said scientists were gonna be great at branding. Put simply, power density is just how much stuff it takes to get your energy; how much land or other physical resources. And we measure it by how many watts you can get per square meter, or liter, or kilogram – which, if you’re like us…probably means nothing to you.

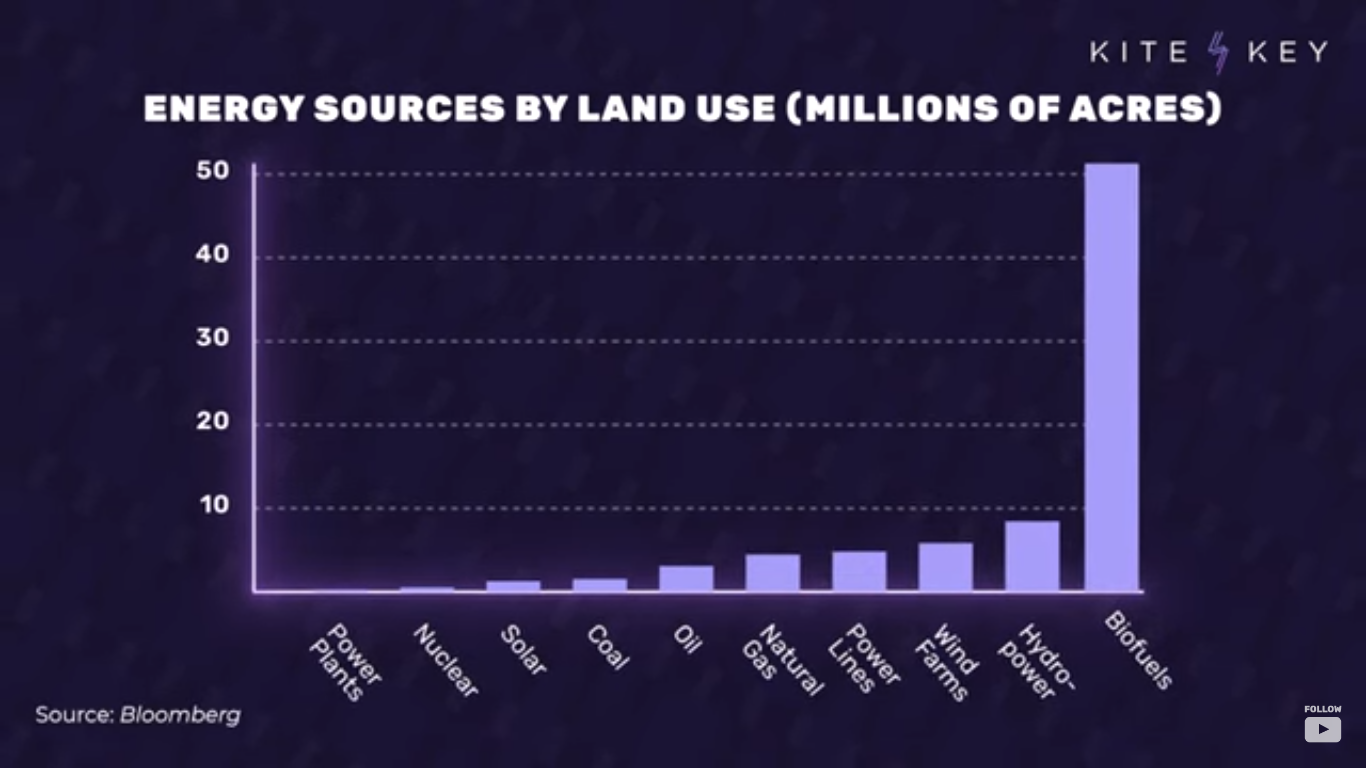

So let’s put this in tangible terms. Just about the worst energy source America has by the standards of power density are biofuels, things like corn-based ethanol. Biofuels only provide less than 3% of America’s energy needs–and yet, because of the amount of corn that has to be grown to produce it … they require more land than every other energy source in the country combined. Lots of resources going in, not much energy coming out–which means they’re never going to be able to be a serious fuel source.

Look, no one said scientists were gonna be great at branding. Put simply, power density is just how much stuff it takes to get your energy; how much land or other physical resources. And we measure it by how many watts you can get per square meter, or liter, or kilogram – which, if you’re like us…probably means nothing to you.

So let’s put this in tangible terms. Just about the worst energy source America has by the standards of power density are biofuels, things like corn-based ethanol. Biofuels only provide less than 3% of America’s energy needs–and yet, because of the amount of corn that has to be grown to produce it … they require more land than every other energy source in the country combined. Lots of resources going in, not much energy coming out–which means they’re never going to be able to be a serious fuel source.

Now, that’s an extreme example, but once you start to see the world in these terms, you start to realize why our choice of energy sources isn’t arbitrary. Coal, for example, is still America’s second largest source of electricity, despite the fact that it’s the dirtiest and most carbon-intensive way to produce it. Why do we still use so much of it? Well, because it’s significantly more affordable…in part because it’s way less resource-intensive.

Now, that’s an extreme example, but once you start to see the world in these terms, you start to realize why our choice of energy sources isn’t arbitrary. Coal, for example, is still America’s second largest source of electricity, despite the fact that it’s the dirtiest and most carbon-intensive way to produce it. Why do we still use so much of it? Well, because it’s significantly more affordable…in part because it’s way less resource-intensive.

An energy source like offshore wind, for example, is so dependent on materials like copper and zinc that it would require six times as many mineral resources to produce the same amount of power as coal. And by the way, getting all those minerals out of the ground…itself requires lots and lots of energy.

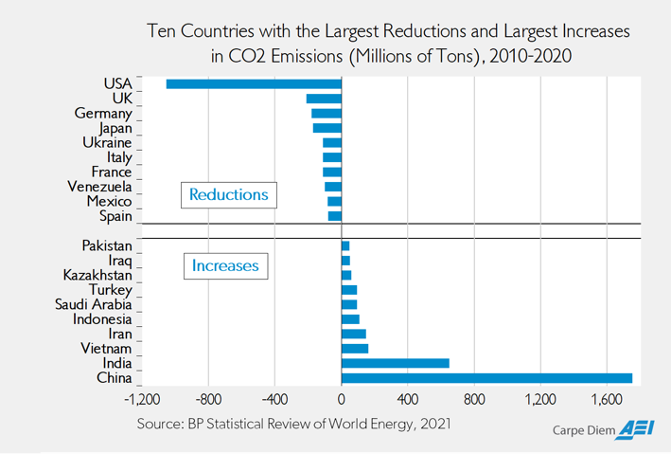

Now, the good news is that America has actually been cutting way down on its use of coal in recent years, thanks largely to technological breakthroughs that brought us cheap natural gas as a replacement. And because natural gas emits way less carbon than coal, that reduced our carbon emissions from electricity generation by more than 30%.

An energy source like offshore wind, for example, is so dependent on materials like copper and zinc that it would require six times as many mineral resources to produce the same amount of power as coal. And by the way, getting all those minerals out of the ground…itself requires lots and lots of energy.

Now, the good news is that America has actually been cutting way down on its use of coal in recent years, thanks largely to technological breakthroughs that brought us cheap natural gas as a replacement. And because natural gas emits way less carbon than coal, that reduced our carbon emissions from electricity generation by more than 30%.

In fact, the government reports that switching over to natural gas did more than twice as much to cut carbon emissions as renewables did in recent years. Why did natural gas progress so much faster than renewables? It wasn’t an accident.

Energy is a little like money: You have to spend it to make it. To get usable natural gas, for example, you’ve first got to drill a well, process and transport the gas, build a power plant, and generate the electricity. But the question is how much energy are you getting back for your investment? With natural gas, you get about 30 times as much power out of the system as you put into creating it. By contrast, with something like solar power, you only get about 3 1/2 times as much power back.

In fact, the government reports that switching over to natural gas did more than twice as much to cut carbon emissions as renewables did in recent years. Why did natural gas progress so much faster than renewables? It wasn’t an accident.

Energy is a little like money: You have to spend it to make it. To get usable natural gas, for example, you’ve first got to drill a well, process and transport the gas, build a power plant, and generate the electricity. But the question is how much energy are you getting back for your investment? With natural gas, you get about 30 times as much power out of the system as you put into creating it. By contrast, with something like solar power, you only get about 3 1/2 times as much power back.

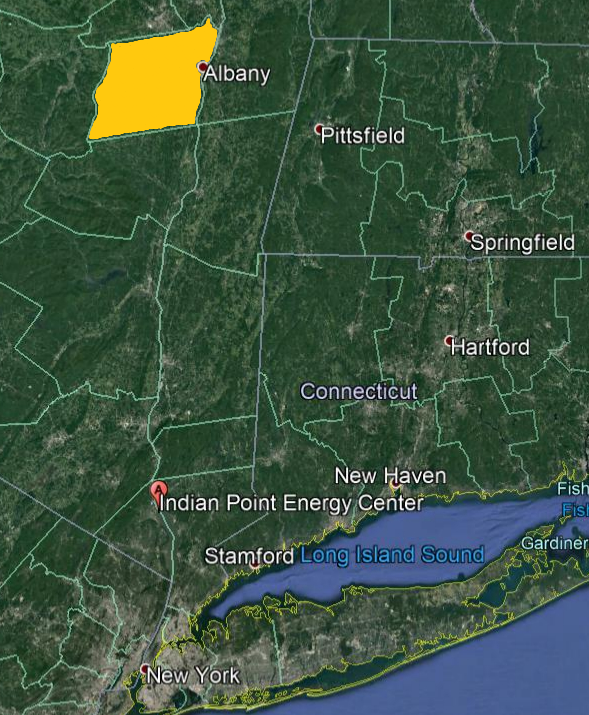

Replacing the now closed Indian Point nuclear power plant would require covering all of Albany County NY with wind mills.

Addendum from Michael J. Kelly

Energy return on investment (EROI) The debate over decarbonization has focused on technical feasibility and economics. There is one emerging measure that comes closely back to the engineering and the thermodynamics of energy production. The energy return on (energy) investment is a measure of the useful energy produced by a particular power plant divided by the energy needed to build, operate, maintain, and decommission the plant. This is a concept that owes its origin to animal ecology: a cheetah must get more energy from consuming his prey than expended on catching it, otherwise it will die. If the animal is to breed and nurture the next generation then the ratio of energy obtained from energy expended has to be higher, depending on the details of energy expenditure on these other activities. Weißbach et al. have analysed the EROI for a number of forms of energy production and their principal conclusion is that nuclear, hydro-, and gas- and coal-fired power stations have an EROI that is much greater than wind, solar photovoltaic (PV), concentrated solar power in a desert or cultivated biomass: see Fig. 2. In human terms, with an EROI of 1, we can mine fuel and look at it—we have no energy left over. To get a society that can feed itself and provide a basic educational system we need an EROI of our base-load fuel to be in excess of 5, and for a society with international travel and high culture we need EROI greater than 10. The new renewable energies do not reach this last level when the extra energy costs of overcoming intermittency are added in. In energy terms the current generation of renewable energy technologies alone will not enable a civilized modern society to continue!

In human terms, with an EROI of 1, we can mine fuel and look at it—we have no energy left over. To get a society that can feed itself and provide a basic educational system we need an EROI of our base-load fuel to be in excess of 5, and for a society with international travel and high culture we need EROI greater than 10. The new renewable energies do not reach this last level when the extra energy costs of overcoming intermittency are added in. In energy terms the current generation of renewable energy technologies alone will not enable a civilized modern society to continue!

On Energy Transitions

Postscript

Ron, you might want to add the following:

Bud: What is the difference and meaning of buffered vs unbuffered EROI?

Grok 3 beta: In the context of energy systems, EROI stands for Energy Return on Investment, a metric used to evaluate the efficiency of an energy source by comparing the amount of energy it delivers to the amount of energy required to produce it. The terms “buffered” and “unbuffered” EROI refine this concept by addressing how energy inputs and outputs are accounted for, particularly in relation to societal energy needs and system boundaries.

Unbuffered EROI

Definition: Unbuffered EROI (sometimes called “standard EROI” or “point-of-extraction EROI”) measures the energy return at the point where the energy resource is extracted or produced, without considering the additional energy costs required to refine, transport, or convert it into a form usable by society.

Meaning: It focuses solely on the direct energy inputs and outputs at the source. For example, in oil production, unbuffered EROI would compare the energy content of crude oil extracted from a well to the energy spent drilling and pumping it out, ignoring downstream processes like refining or distribution.

Formula:

Unbuffered EROI=Energy Output (e.g., crude oil energy content)Energy Input (e.g., extraction energy)text{Unbuffered EROI} = frac{text{Energy Output (e.g., crude oil energy content)}}{text{Energy Input (e.g., extraction energy)}}text{Unbuffered EROI} = frac{text{Energy Output (e.g., crude oil energy content)}}{text{Energy Input (e.g., extraction energy)}}

Significance: This gives a raw, high-level view of an energy source’s efficiency but can overestimate its practical value because it doesn’t account for the energy losses or investments needed to make the energy usable.

Buffered EROI

Definition: Buffered EROI (sometimes referred to as “net EROI” or “delivered EROI”) expands the system boundary to include additional energy costs beyond extraction, such as processing, refining, transportation, and delivery to the end user. It reflects the energy available after these “buffering” steps.

Meaning: This metric provides a more realistic picture of how much usable energy society actually gets from a resource. For instance, in the oil example, buffered EROI would subtract the energy used to refine crude oil into gasoline and transport it to gas stations, giving a lower but more practical value.

Formula:

Buffered EROI=Energy Delivered to SocietyEnergy Input (extraction + processing + transport, etc.)text{Buffered EROI} = frac{text{Energy Delivered to Society}}{text{Energy Input (extraction + processing + transport, etc.)}}text{Buffered EROI} = frac{text{Energy Delivered to Society}}{text{Energy Input (extraction + processing + transport, etc.)}}

Significance: It highlights the diminishing returns as energy systems become more complex or as higher-quality energy (e.g., electricity) is required to support the process, making it more relevant for understanding energy sustainability.

Key Differences

System Boundary:

Unbuffered: Narrow focus on extraction/production.

Buffered: Broader focus, including downstream energy costs.

Value:

Unbuffered EROI is typically higher because it ignores additional energy losses.

Buffered EROI is lower but more representative of real-world usability.

Application:

Unbuffered: Useful for comparing raw energy potential across sources (e.g., oil vs. solar at the point of capture).

Buffered: Better for assessing an energy source’s contribution to societal needs or economic viability.

Example

Solar Panels:

Unbuffered EROI might measure the energy generated by a solar panel divided by the energy used to manufacture it, yielding a high ratio (e.g., 10:1).

Buffered EROI would also subtract energy losses from storage (e.g., batteries), transmission, and conversion inefficiencies, resulting in a lower ratio (e.g., 4:1).

Oil:

Unbuffered EROI for a new oil field might be 20:1 (energy in crude oil vs. drilling energy).

Buffered EROI might drop to 5:1 after refining and transport costs are included.

Why It Matters

The distinction is critical for energy policy and sustainability debates. A high unbuffered EROI might make an energy source look promising, but a low buffered EROI could reveal that it’s less viable when all societal costs are considered. As energy transitions progress (e.g., from fossil fuels to renewables), buffered EROI becomes increasingly important to ensure the net energy available supports civilization’s needs.

LikeLike

Thanks Bud. I don’t see buffered EROI including the additional cost of intermittent energy from wind and solar. Storage is mentioned, but not the standby baseload electricity generators to address the problem of matching electricity demand on windless (or too windy) nights.

LikeLike