For those who prefer reading, below is an excerpted transcript lightly edited from the interview, including my bolds and added images.

Hey everyone, it’s Andrew Klavan with this week’s interview with Bjorn Lomborg. I met Bjorn, he probably doesn’t remember this, but I met him many, many years ago at Andrew Breitbart’s house. Andrew brought Bjorn over to talk in LA and I listened to him talking about all the simple and inexpensive things that could be done to make actual change and do actual good in terms of climate change, which I think at that point was still global warming.

And you know, we had a small audience, and I asked the question, well, if these are so such smart, cheap ideas, why don’t politicians do them? And Bjorn said, well, because that wouldn’t give them the chance to display their virtue. And I thought, here’s a man who not only knows about science, but actually knows about human nature. And I’ve been following him ever since.

He is a president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, a visiting fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, an author of False Alarm and Best Things First, the best writer, I think, on climate issues and other issues. Bjorn, it’s good to see you.

Andrew, it’s great to be here. And I do remember that event, although I remember it for seeing the guy who played on Airplane. Sorry. So I remember that because it was it’s still one of my favorite movies. It’s one of the greatest movies ever made, I think. It really is very, very funny. Yeah.

On a totally different direction. So I was watching with great approval Donald Trump’s appearance at the United Nations. I guess it would be when we’re playing this last week. And he he had this. I’m just going to read just a little bit of the speech. He said in the 1920s and the 1930s, they said global cooling will kill the world. We have to do something. Then they said global warming will kill the world. But then it started getting cooler. So now they could just call it climate change because that way they can’t miss if it goes higher or lower, whatever the hell happens. It’s climate change. It’s the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world, in my opinion. Do you agree with that?

So I get where he’s coming from. And I think there’s some some truth to this. I mean, Donald Trump always speaks in larger than real life words. Yes. So it’s not a con job. There is a problem. And actually, in some sense, bizarrely, as it may sound, you know, the world is built all of our infrastructure is built to live at the temperature that we’ve had for the last hundred or two hundred years. That’s true in Los Angeles. That’s true in Boston. It’s true everywhere in the world. And so if it gets colder or if it gets warmer, that will be a problem. So there is an issue here.

But obviously, it’s vastly exaggerated when people then talk about the end of the world. You may remember that this was one of the favorite terms of Biden, but not just Biden, but pretty much everyone for the last four years and certainly more as well. That this is an existential crisis. There was a recent survey by the OECD, so in all rich countries in the world, where they found that percent of all people believe that unmitigated climate change, so climate change we don’t fix, will likely or very likely lead to the end of mankind. And that, of course, is a very different statement.

There is a problem, that’s true. It’s not the end of the world.

But the end of the world is a great way to get funding.

And that’s why people are playing it out. But it doesn’t make for good policy. Remember, if you think the end of the world is near, you’re going to throw everything in the kitchen sink at this, which, of course, is what the campaigners would like you to do. But you will probably waste an incredible amount of resources because you’re just going to try everything.

Climate change is a problem. So I disagree with Trump there. But yes, there is an incredible amount of exaggeration. And I agree with him there. So there’s I mean, the climate changes but we’re not living in a glass bubble. And we’ve even in I don’t know, I guess it was the late 19th century, the Thames in London froze over and people went skating on it. It’s so there are these big changes and there have been ice ages, obviously. How much of this or do we know how much of this is is caused by human beings?

I have to preface this with saying I’m a social scientist, so I work a lot on the costs and the benefits of us doing policies against climate change. I’ve met with a lot of the natural scientists who study all this. Please don’t do this at home, but I’ve read the UN climate panel report, most of the pages, not all of them. And it’s incredibly boring, but it’s also very, very informative. So so I have a reasonably good take on this. And what they tell us is that the majority of the recent warming that we’ve seen is due to climate change.

I have no idea to evaluate that, no way of independently evaluating that is due to natural climate change or is manmade, due to mankind. So is it mostly due to us emitting CO from burning fossil fuels?

So there is a significant part of what’s changed over the last century or thereabouts, which is about two degrees Fahrenheit or one degree Celsius. So that’s something and that’s something we should look at. But also, we should get a sense of what’s the total impact of this. Well, actually, climate economics have spent the last three decades trying to estimate: what’s the total cost of everything that happens with climate change.

So, you know, there are lots of negatives. There’ll be more heat waves. There’ll possibly be stronger storms. There’s also going to be fewer cold waves, which is actually a good thing. There’s also going to be CO2 fertilization. So we’ll have more greenery. You know, if you add all the negatives and all the positives, it become a net negative. That’s why it’s a problem. But also get a sense of this.

If you look across all of the studies that we’ve done, we estimate the net negative impact today is about 0.3% of GDP. So yeah, a problem, not the end of the world. And it’s crucial to say, if you look out till 2100 which is sort of the standard time frame, which is a long time from now, we estimate if we do nothing more about climate change, so we end up with three degrees Celsius, so about degrees 5.6 Fahrenheit, then the cost will be about to 2 to 3% of global GDP every year.

That’s certainly not nothing. That’s a lot of trillions of dollars. But again, it’s 2 to 3%. It’s not, you know, the end of mankind, It’s not anywhere near a hundred percent. And this is not me saying this. This is the guy William Nordhaus from Yale university, the only guy to get the Nobel prize in climate economics. And Richard Tol one of the most quoted climate economists in the world. They’ve done separate studies. One to find 2%, the other one to find 3%. That’s the order of magnitude we’re talking about. And just for, for added emphasis, remember by then everyone in the world will be much, much better off.

Just like if you compared people from back in 1925 and until today, the UN on its standard trajectory estimate, the average person in the world by the end of the century will be somewhere around 450% as rich as he or she is today. That’s not the US that will. And you know, people come from Denmark and other rich countries might only be 200% as rich, but many in Africa and elsewhere will be a thousand percent richer. So on average, because of climate change, it will feel like they’re only 435% as rich, which sort of emphasizes, yes, that’s a problem. I would rather have a world that’s 450% as rich trather than one that’s 435%. But it’s not the end of the world.

It’s still a fantastically much better world, just a slightly less fantastically much better world. And that less money that people will have will mean less money you have to spend, what, shoring up buildings. And so the way they measure that is actually in equivalence of how much you would need to get compensated to live with the problems.

So we don’t actually look at whether people will fix it or not. You know, it’s a bit like, if you have a slightly dangerous job, you get more money. And that’s basically a way of saying, but you’ll also have to live with that constant slightly higher risk of dying. Right. So we’re compensating you for that. That’s the, that’s the amount that we’re talking about. So it’ll feel like you’re only % as rich, although you’ll probably in reality, get all that, that slight extra money to get up to 450%, but then you will also have to live with some problems from climate change.

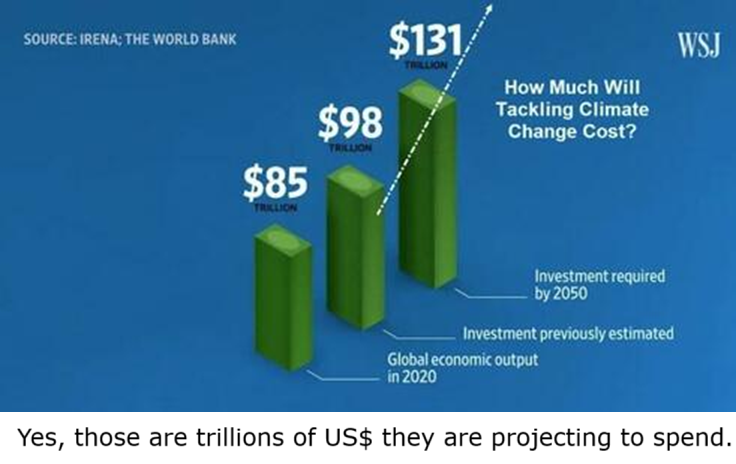

This week I was arguing with a socialist, lovely guy, but just the guy who believes that like all money should be redistributed. And I was pointing out that this was giving a lot of power to the people in power. And one of the things I sent him was this article you wrote in the, in the New York Post, which was exactly the kind of article that makes me angry. And I mean, it makes me frustrated with our politics. I want to read just a couple of sentences. Last year, the world spent over $2 trillion on climate policies. This is Bjorn Lomberg writing in the New York Post. By 2050 net zero carbon emissions will cost an impossible $27 trillion every year. So this, this will choke growth, spike energy costs and hit the poor hardest and still will deliver only 17 cents back on every dollar spent. Meanwhile, mere billions of dollars could save millions of lives. I’d like to take this apart a little bit, but to begin with all the stuff that we are spending this money on, is it doing anything? Will it have any effect?

It will. I mean, what, what are we spending money on and what will it do? So these $2 trillion, that’s sort of the official number from the International Energy Agency and many others. It’s a very soft number because obviously what goes into all this money, surprisingly, it’s also all the cost into EVs or electric cars, which of course gives you a thing that can drive you from place A to B, at least if it’s been charged. So, I mean, there are some benefits to this. It’s also spending on solar panels and wind turbines, which again, obviously gives you electricity when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing. It actually also gives you higher electricity costs all the other times, because you now need to have backup power for when it’s not shining or windy, and that capital is being used less.

So there’s a lot of spending, it’s a very big headline number. There’s $2 trillion, everyone uses it, but it, but it’s not all that informative, because the global economy is about a hundred trillion dollars. It means we’re spending 2% on stuff that we probably wouldn’t have done had we not been scared witless on climate change. And that’s a waste. I mean, remember the total spend on healthcare is perhaps 8%. The total spend on education globally is about 5%.

These are big numbers. This is something that could have done a lot of good elsewhere. But I think the real point here is to say people want to take us to a cost that’s much, much, much higher. Remember all the world’s governments, almost all the world’s government now, not Donald Trump and the US, but most governments have pledged in one form or another that we’re going to go net zero around 2050 or shortly thereafter. But nobody looked at what the cost of this will be, which is a little surprising. Because the numbers I’m going to show you suggest that this one single promise is about a thousand times more expensive than the second costliest policy to which the world has ever committed, which was the Versailles treaty back in 1919, had Germany actually paid all the money it was supposed to. That cost was about half a trillion dollars in today’s money, which of course is why Germany never paid it. But now we’re talking about something that is going to be in the order of a thousand to two to 3000 times more costly.

Yet nobody’s looked at what the cost will be and what will be the benefits?

There’s no official estimate of this.

So two years ago, a professor from Yale university, Robert Mendelsohn, gathered a lot of really smart climate economists to try to estimate what’s the cost, and what’s the benefit of net zero. A lot of those really, really smart economists ended up chickening out. You can understand why it’s a really hard question. You’re also asking what will happen in the next hundred years and you’re trying to put estimates on it. At the end of the day, they published a big study published in the journal of climate change economics, which is a period article.

And they had one benefit estimate and three cost estimates. So this is obviously not great, but it’s the only thing the world has. And so that gives you a sense of how much will this cost and how much good will do. If you take the average of these three cost estimates, that gives you $27 trillion in cost per year throughout the 21st century. That’s where that number comes from. $27 trillion. So that’s about a quarter of global GDP right now, because we’re going to be much richer, that is only going to be about 7% of global GDP across the 21st century. But you know, that’s an enormous cost that’s on the magnitude of bigger than education, a bit smaller than healthcare and for everyone in the world, that’s a lot of money.

Now, if this gave you a lot of benefits that might be worthwhile. I mean, we pay a lot of money for stuff that’s good, but we’ve already established that even if we could entirely get rid of climate change, it would only reduce costs by two to 3%. So spending 7% to get rid of two to 3% is a bad deal, but unfortunately net zero by 2050 means we’ll only get rid of part of it, right? Because we’ll already have cost a lot of climate change. So the net benefit is only about 1% of GDP across the century or about four and a half trillion dollars.

So there’s a real benefit. That’s why climate change is real. There’s a real benefit to net zero, but the benefit is much, much lower than the cost. So $4.5 trillion in benefits, $27 trillion in cost every year in the 21st century, we’ll be paying much, much more than the benefits will generate for the world. That’s just a bad deal. There’s no other way to put it.

And the fact that we’re not honest about this and that most people just are not honest about it is one of the reasons why we’re wasting money and spending it so badly. The last bit of the quote that you just said was we could do so many other good things. Remember, most people in the world are not living in nice countries like the US or Denmark. Most people are not considering, you know, the biggest problem which of the many programs and series they want to follow are, am I going to take first or watch first? Or, you know, what kind of takeout am I going to have? They worry about their kids dying from easily curable infectious diseases, not having enough food, having terrible education, not enough jobs, corruption, all these other things. And the truth is we could solve many of these problems, not all of them, but many of them to save millions of lives at a fraction, a tiny, tiny fraction of this cost. So instead of talking trillions, we’re talking billions.

Why is it that we’re so obsessed with spending trillions to do almost no good a hundred years from now, instead of spending billions and doing a lot of good right now to avoid people dying from tuberculosis and malaria, avoid people having terrible education, getting better economies, all these things that we know work at much lower cost. That’s my central question to all these feel gooders. I mean, I know that they want to feel good about themselves, but in some sense, I would like to believe that they actually want to have done good at the end of the day.

I think it’s much more a question of saying, if I am doing effective policies, there’s not much money to hand out to friends and to buy more votes and all that kind of stuff. Whereas if I am overseeing, you know, an enormous amount of spending on stuff that doesn’t really matter. So I can just spend it on whatever. Then clearly I have a lot more latitude and a lot more opportunity to get people to like me and to show what a good person I am. So I think in some sense, it’s just plain politics. You know, if you’re saying the world is on fire and you’re at risk. But vote for me and I can save your kids. And it’s only going to cost you 7%. I can see, you know, why people want to vote for that. But if you’re saying, look, things are fine and just give me a little bit of money and I’ll fix the rest of the problems. It doesn’t quite have the same ring to it, does it?

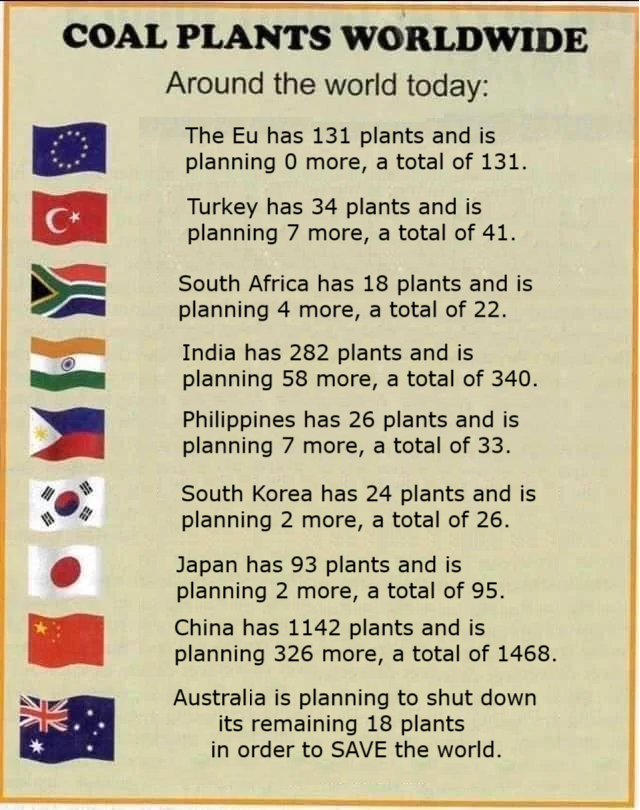

So, so if, if we were to get to net zero, wouldn’t that cripple poor countries? I mean, in other words, it seems to me that people who burn the most fossil fuels are the people who are building up most and the people who are developing most. Whereas we’re sort of, we’ve sort of leveled off, haven’t we?

Yes. So the truth about the $27 trillion is that this is an optimistic estimate, sort of assuming that we’re going to be smart. But I don’t know what the climate future is going to look like. I don’t think anyone really knows, but we have a good sense that we’re good at, you know, innovating stuff. And we know how to get CO2 free energy. We can do it with nuclear. We also know we can get some from solar and wind. We’ll probably have more batteries. We’ll have lots of things. I think the world was sort of, you know, stumble through and we’ll be okay. But the point is we could have been much, much better off.

Does that affect your sense of politics at all? Oh, of course it does. And I’m disappointed that half the world would tend to dismiss a lot of this because these are inconvenient facts, With that said though I also talk about all the incredibly important things we could do in the poor part of the world. This is not true for most of the world, this is a very Western, kind of rich world situation where we have this very clear distinction between right and left. And, and a lot on the left, I think have sort of gone off on the deep end on some of these things.

For instance, on climate change, which has become this identifying totem, that they worship, and not in a smart way. Remember a lot of standard left-wing belief was about helping the downtrodden, which I perfectly agree with. And I think a lot of people would agree, we need to get poor people out of poverty. That’s a terrible situation and it destroys human dignity and liberty and all kinds of things. We should absolutely do something about that. But the truth is that’s where, you know, seven eighths of the world’s population is because they know poverty and they want to get out of it.

Although when you go to these events in New York and, and elsewhere, even politicians from Africa and elsewhere, they’ll of course say all the platitudes that come along with getting some funding from rich Western nations. But in the private cocktail conversations afterwards, you know, they don’t look at Germany and the UK and say: oh yes, deindustrialization and incredibly high energy costs, that’s what we want. No, they look at China because they want to get rich like China did.

And China of course got rich famously by dramatically increasing its energy consumption through coal. At its lowest China’s energy from renewables was 7.5%, and now it’s up to about 11%. So people think, oh China is this green giant, but no it’s not. It gets the vast majority of its energy from coal. And not surprisingly, because that has been historically the cheap opportunity to drive your economy and development.

Where has an economy evah advanced w/out energy,

from horse power to the water wheel to the steam engine”…

In Holland, not the water wheel but the wind mill. Heed

H.I.Mencken “Do not be afraid. “

LikeLike