Surplus Arctic Ice late August 2025

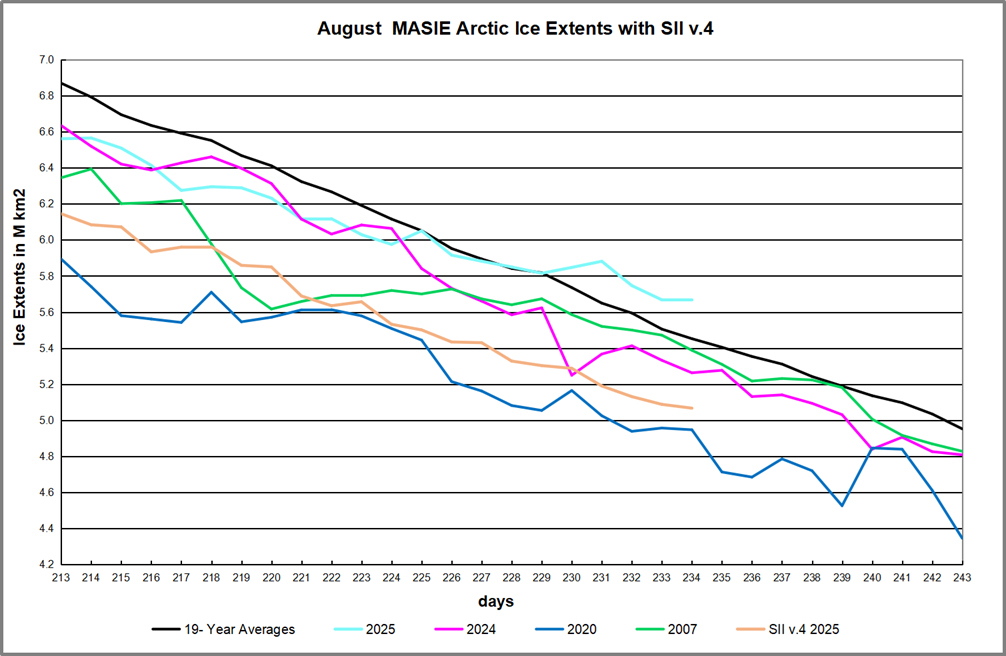

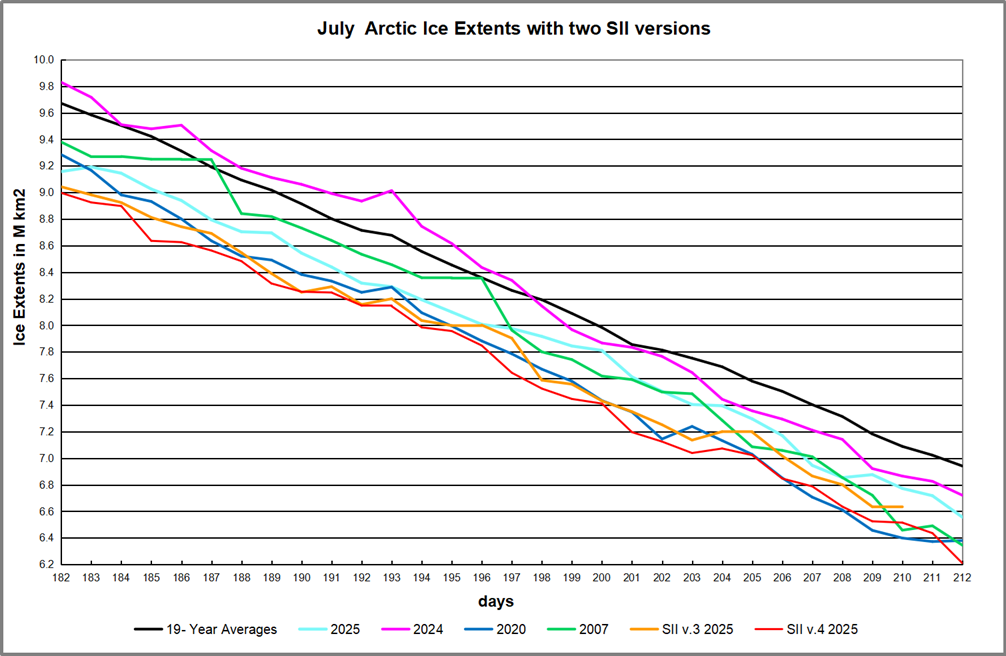

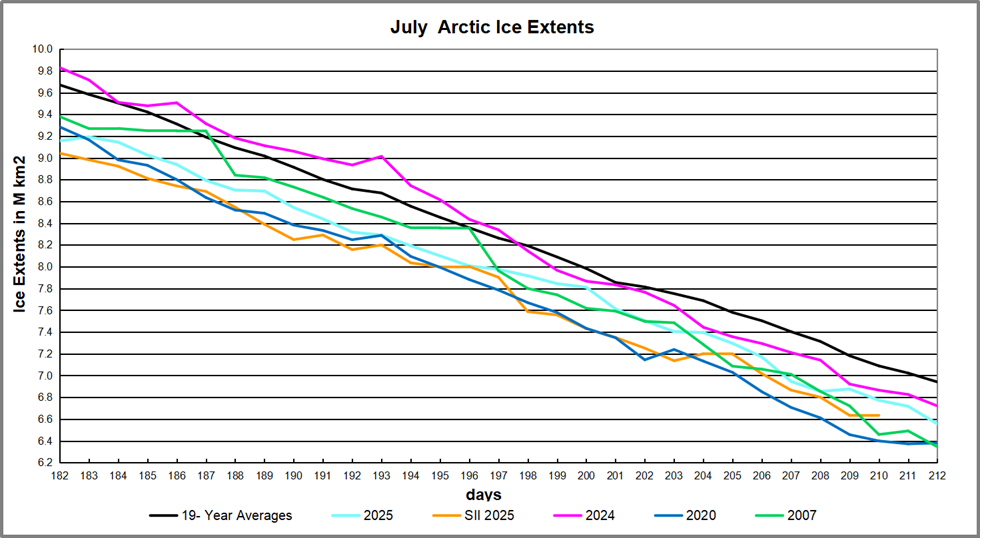

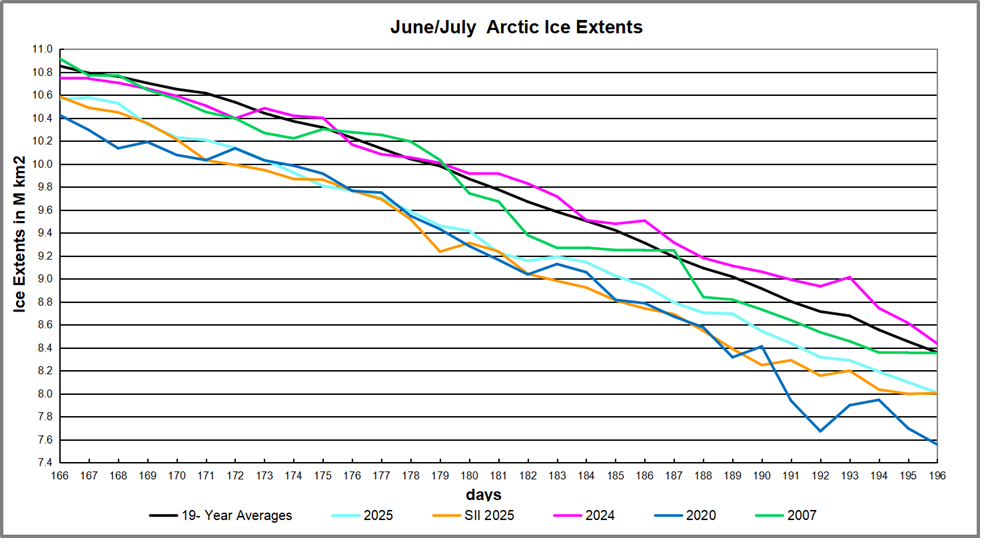

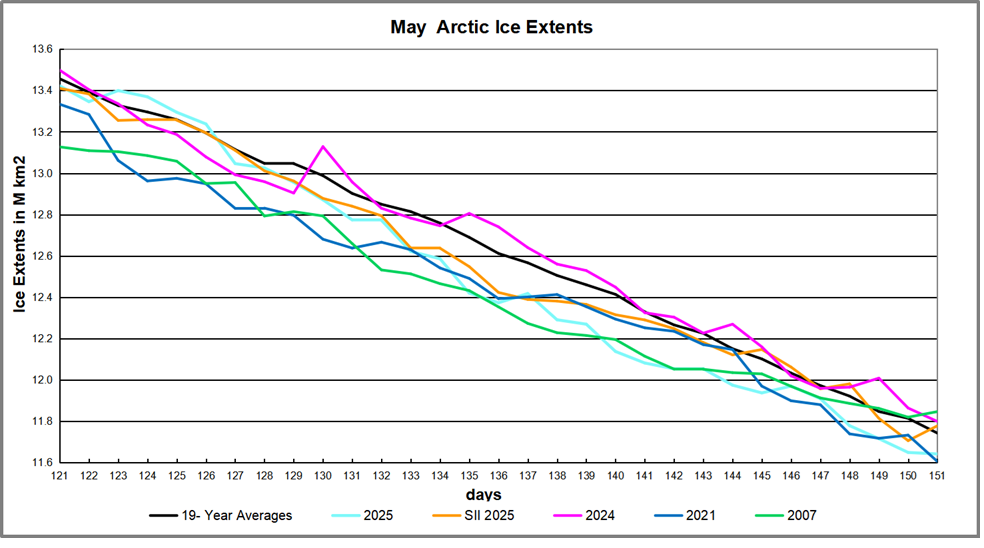

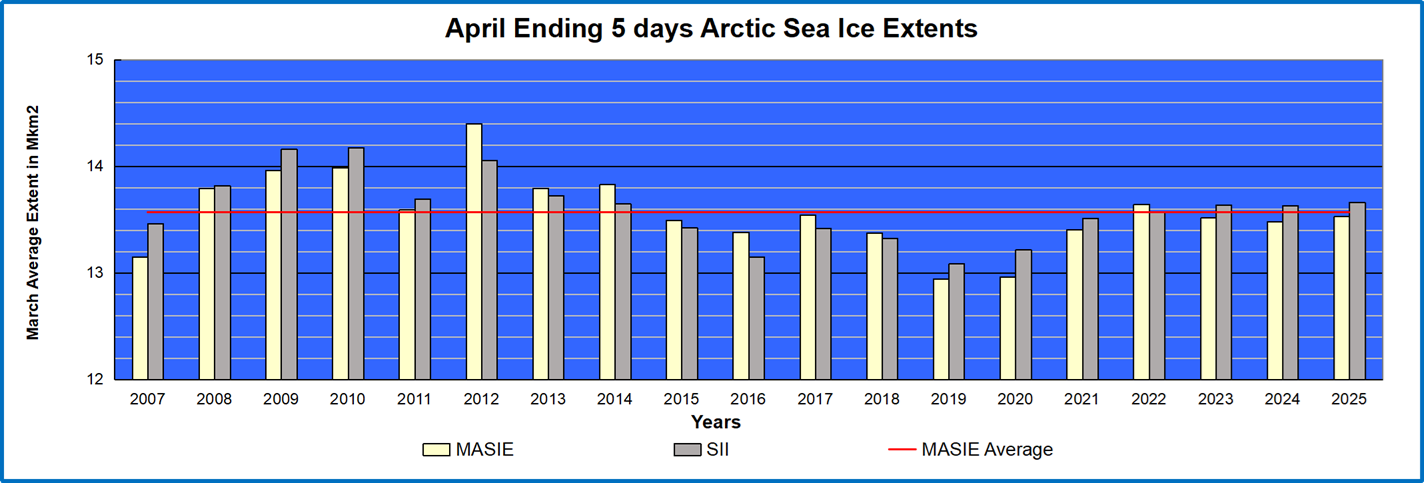

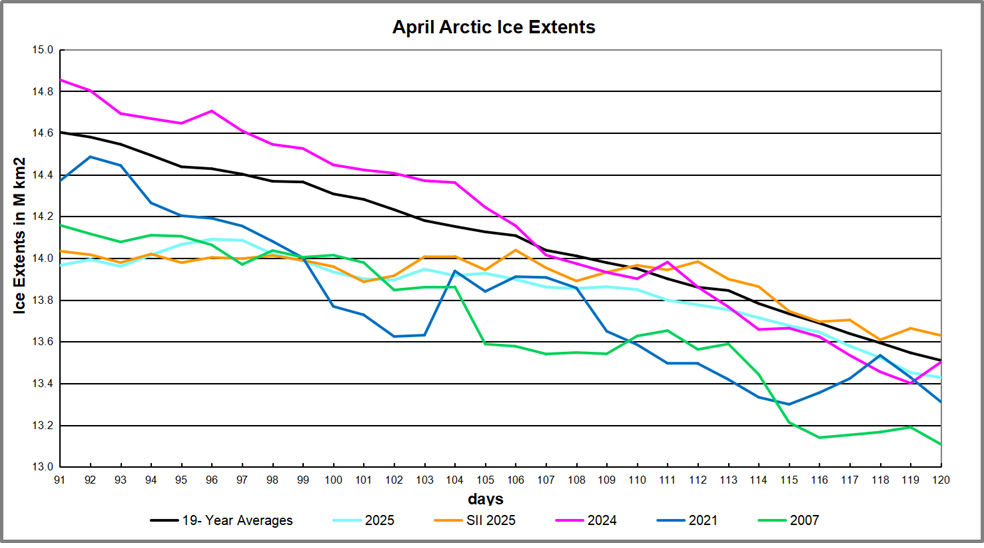

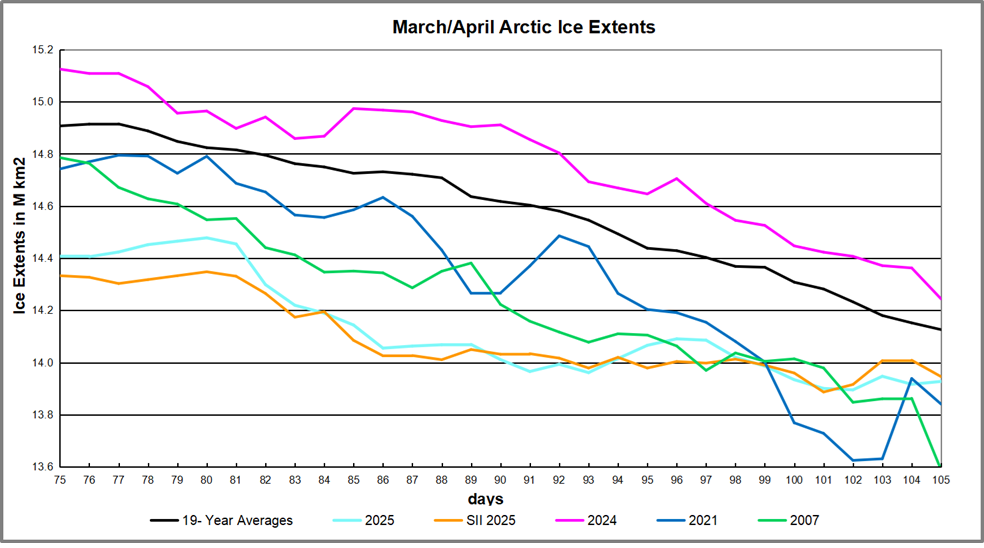

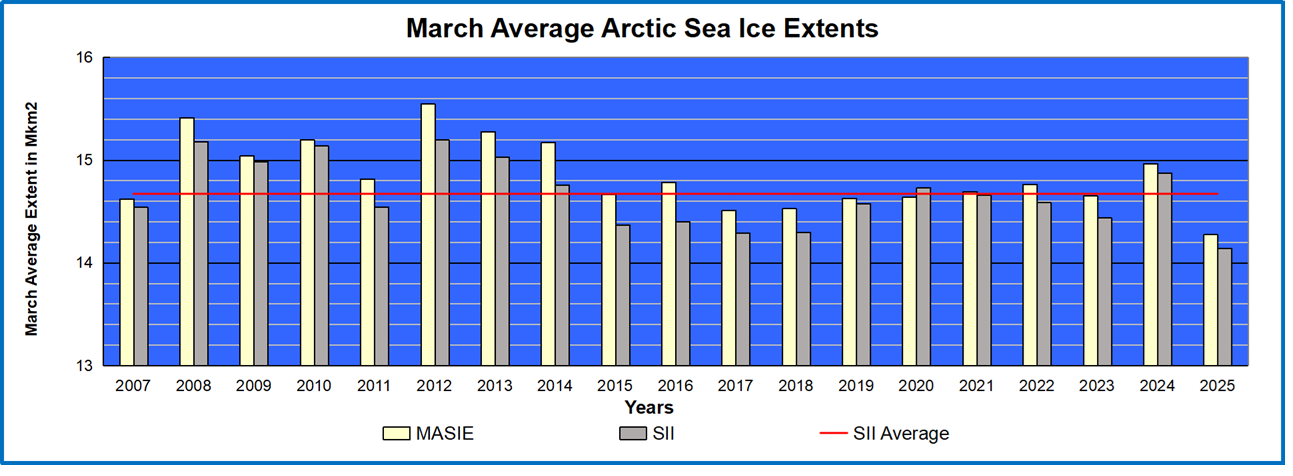

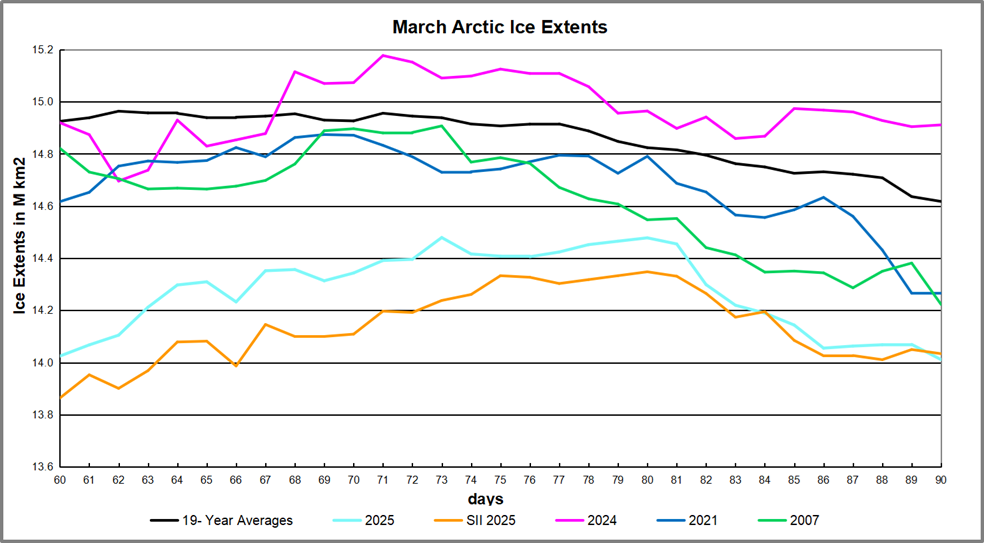

After a sub-par March maximum, by end of May 2025 Arctic ice closed the gap with the 19-year average. Then in June the gap reopened and in July the melting pace matched the average, abeit four days in advance of average. In mid-August MASIE showed the Arctic ice extent matching the 19-year average. Now with a week to go Arctic ice has been above average for the last five days, by over +200k km2 yesterday.

During August the average year loses 1.9M km2 of ice extent. MASIE on day 213 was 308k km2 down, and the gap closed steadily, going into surplus on day 230. Note 2020 and 2024 were well below average mid-August. 2024 ended nearly average, while 2020 went down almost off the chart. Meanwhile SII v.4 started August ~400k km2 lower than MASIE, increasing to 600k km2 yesterday. More on what happened to SII in footnote.

The regional distribution of ice extents is shown in the table below. (Bering and Okhotsk seas are excluded since both are now virtually open water.)

| Region | 2025234 | Ave. Day 234 | 2025-Ave. | 2020234 | 2025-2020 |

| (0) Northern_Hemisphere | 5665223 | 5452280 | 212942 | 4947191 | 718032 |

| (1) Beaufort_Sea | 912878 | 636530 | 276349 | 802063 | 110815 |

| (2) Chukchi_Sea | 456078 | 382204 | 73873 | 382512 | 73565 |

| (3) East_Siberian_Sea | 597683 | 465057 | 132626 | 248241 | 349443 |

| (4) Laptev_Sea | 210514 | 216232 | -5718 | 36330 | 174184 |

| (5) Kara_Sea | 3533 | 70094 | -66561 | 23616 | -20083 |

| (6) Barents_Sea | 0 | 18103 | -18103 | 342 | -342 |

| (7) Greenland_Sea | 124456 | 195018 | -70562 | 227692 | -103236 |

| (8) Baffin_Bay_Gulf_of_St._Lawrence | 63370 | 40548 | 22822 | 13063 | 50308 |

| (9) Canadian_Archipelago | 371460 | 348507 | 22954 | 356783 | 14677 |

| (10) Hudson_Bay | 21111 | 34968 | -13858 | 35329 | -14218 |

| (11) Central_Arctic | 2902590 | 3043900 | -141310 | 2820550 | 82040 |

The table shows large surpluses in Eurasian basins Beaufort, Chukchi and E. Siberian, more than offsetting deficits in Central Arctic, Kara and Greenland seas. Hudson Bay is mostly open water at this time of year. 2025 exceeds the average ice extents by 212k km2, or 4%, and is 718k km2 greater than 2020, or 0.7 Wadhams of ice extent.

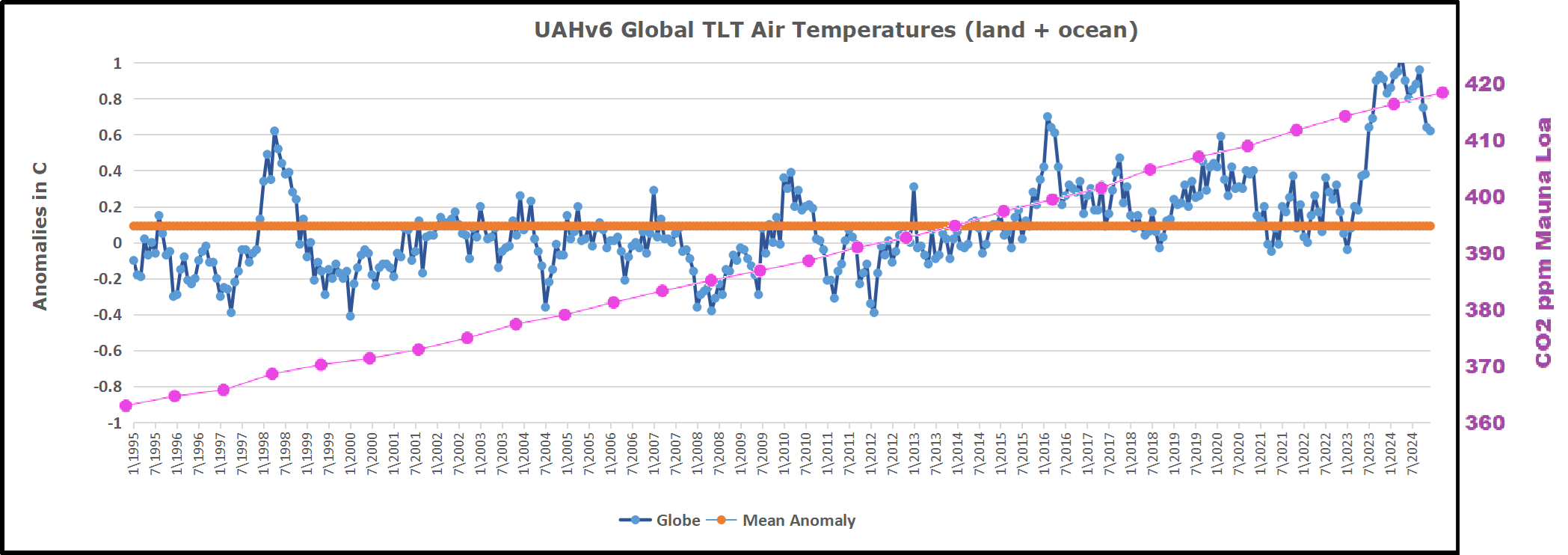

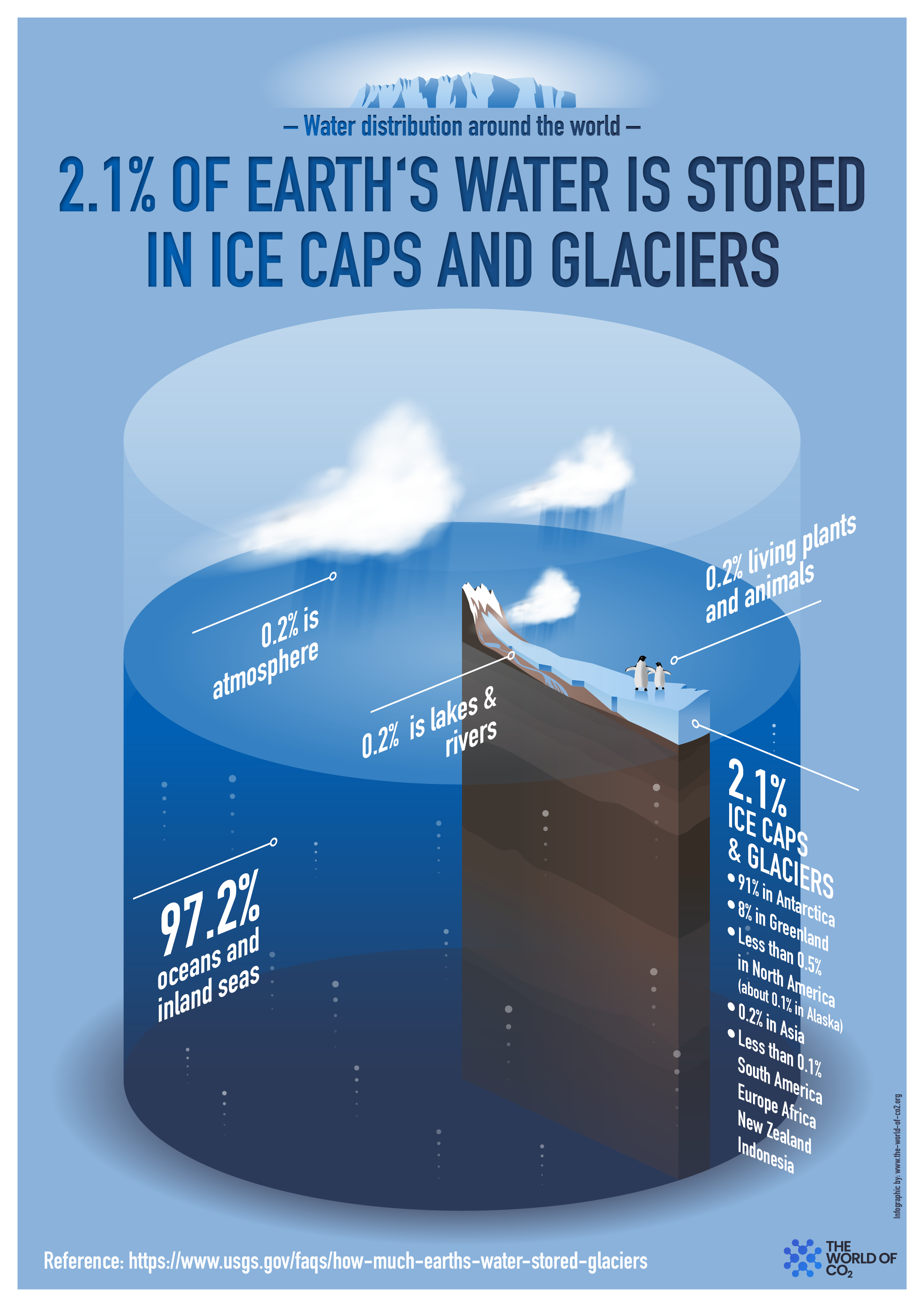

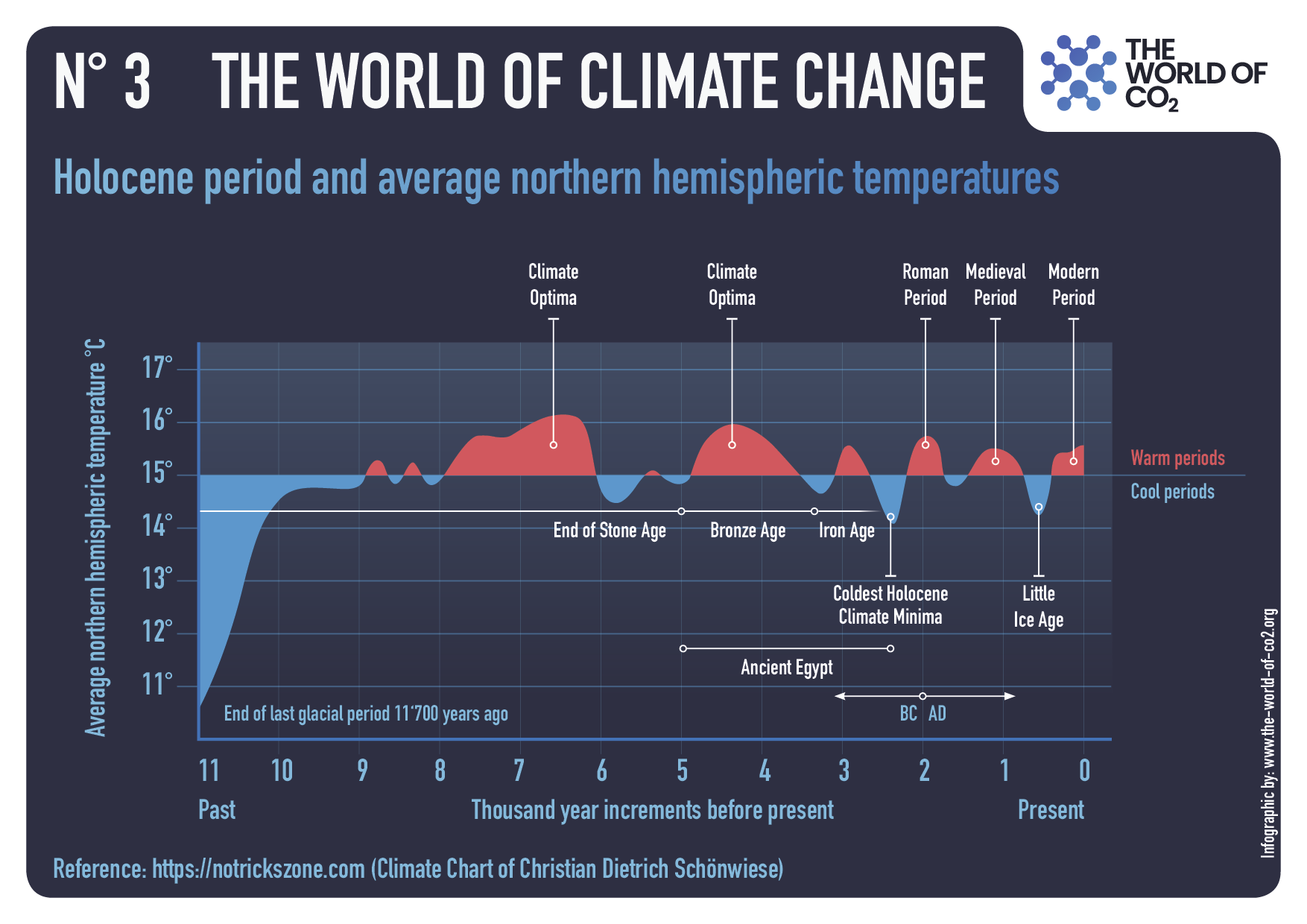

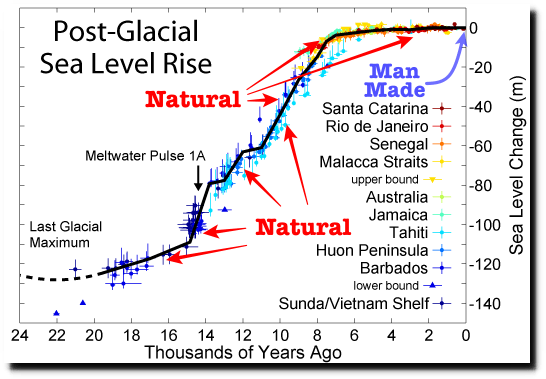

Why is this important? All the claims of global climate emergency depend on dangerously higher temperatures, lower sea ice, and rising sea levels. The lack of additional warming prior to 2023 El Nino is documented in a post SH Drives UAH Temps Cooler July 2025.

The lack of acceleration in sea levels along coastlines has been discussed also. See Observed vs. Imagined Sea Levels 2023 Update

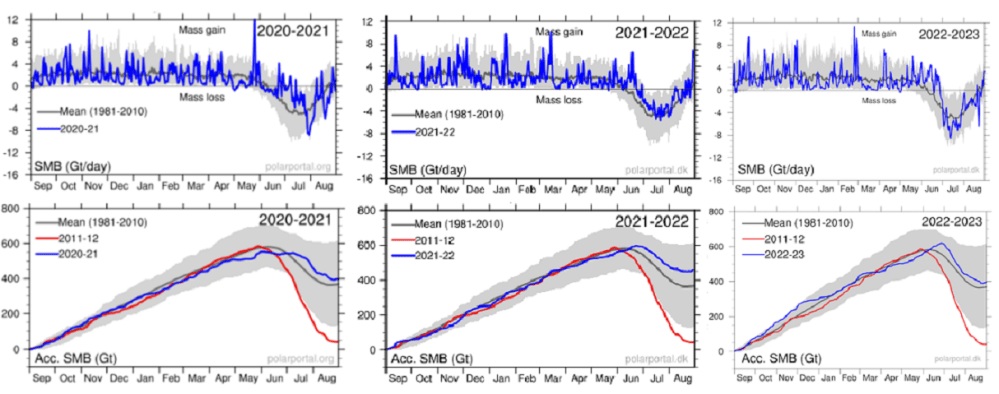

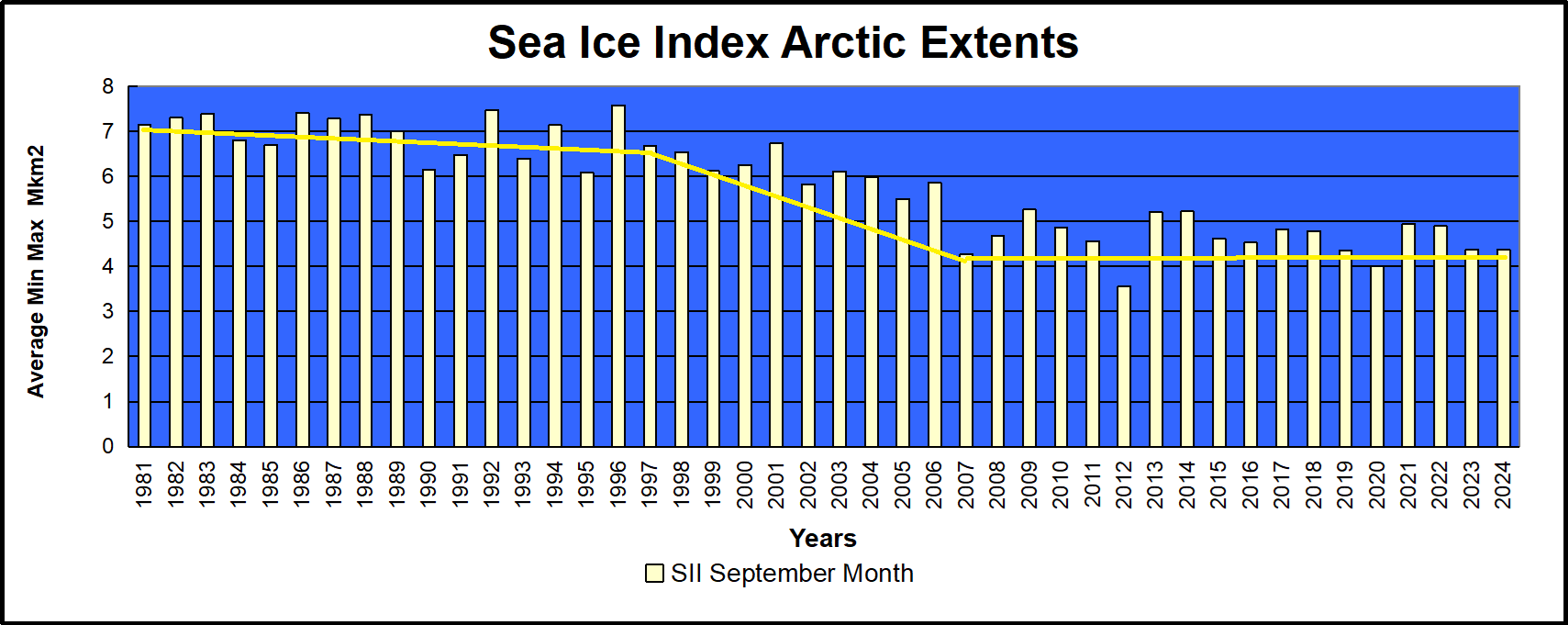

Also, a longer term perspective is informative:

Footnote Regarding SII v.4

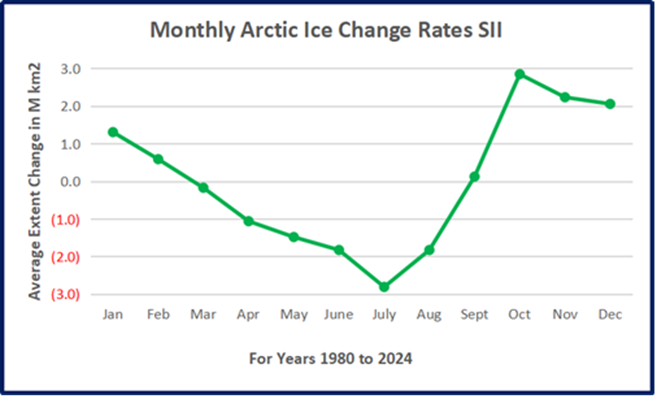

NSDIC acknowledged my query regarding the SII (Sea Ice Index) dataset. While awaiting an explanation I investigated further. My last download of the SII Daily Arctic Ice Extents was on July 30, meaning that the most recent data in that file was day 210, July 29. The header on that file was Sea_Ice_Index_Daily_Extent_G02135_v3.

Then on August 1, the downloaded file had the heading Sea_Ice_Index_Daily_Extent_G02135_v4. So it appears that these are now the values from a new version of SII. As I wrote in my query, since March 14 all of the values for Arctic Ice Extents are lower in this new record. The graph above shows the implications for August as an example of estimates from SIIv.4

The change started in January 2025 and will be the basis for future reporting. The logic for this is presented in this document: Sea Ice Index Version 4 Analysis

In June 2025, NSIDC was informed that access to data from the Special Sensor Microwave

Imager/Sounder (SSMIS) onboard the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP)

satellites would end on July 31 (NSIDC, 2025). To prepare for this, we rapidly developed version

4 of the Sea Ice Index. This new version transitions from using sea ice concentration fields

derived from SSMIS data as input to using fields derived from the Advanced Microwave

Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) sensor onboard the Global Change Observation Mission – W1

(GCOM-W1) satellite. On 29 July 2025, we learned that the Defense Department decision to terminate access to DMSP data had been reversed and that data will continue to be available until September 2026.

We are publishing Version 4, however, for these reasons:

• The SSMIS instruments are well past their designed lifespan and a transition to

AMSR2 is inevitable. Unless the sensors fail earlier, the DoD will formally end the

program in September 2026.

• Although access of SSMIS will continue through September 2026, the Fleet

Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center (FNMOC), where SSMIS data

from the DMSP satellite are downloaded, made an announcement that “Support

will be on a best effort basis and should be considered data of opportunity.” This

means that SSMIS data will likely contain data gaps.

• We have developer time to make this transition now and may not in the future.

• We are confident that Version 4 data are commensurate in accuracy to those

provided by Version 3.