Lab Meat: A Pharma Product with Huge Carbon Footprint

Tyler Durden reports at zerohedge Lab-Grown Meat Gets Green Light On US Menus. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

The World Economic Forum’s dietary blueprint for the masses is becoming a reality as lab-grown meat, bugs, and plant-based foods are quickly being adopted under the guise of solving ‘climate change.’ The latest move by elites and governments to reset the global food supply chain is US regulators approving the sale of meat cultivated from Chicken cells. This makes the US the second country worldwide, besides Singapore, to approve the sale of lab-grown fake meat.

The Agriculture Department approved Upside Foods and Good Meat to begin selling “cell-cultivated” or “cultured” chicken meat from labs in supermarkets and restaurants.

“Today’s watershed moment for the burgeoning cultivated meat, poultry and seafood sector, and for the global food industry,” Good Meat said in a statement.

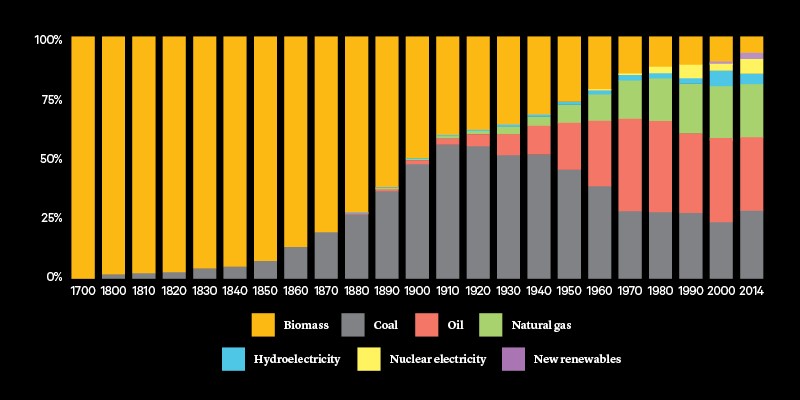

Researchers conducted a life-cycle assessment of the energy needed and greenhouse gases emitted in all stages of production and compared that with beef. One of the current challenges with lab-grown meat is the use of highly refined or purified growth media, the ingredients needed to help animal cells multiply. Currently, this method is similar to the biotechnology used to make pharmaceuticals. This sets up a critical question for cultured meat production: Is it a pharmaceutical product or a food product? -UC Davis

“If companies are having to purify growth media to pharmaceutical levels, it uses more resources, which then increases global warming potential,” according to lead author and doctoral graduate Derrick Risner, of the US Davis Department of Food Science and Technology. “If this product continues to be produced using the “pharma” approach, it’s going to be worse for the environment and more expensive than conventional beef production.”

Cultured Beef Burger grown from stem cells of cattle made by Professor Mark Post of Netherland’s Maastricht University.

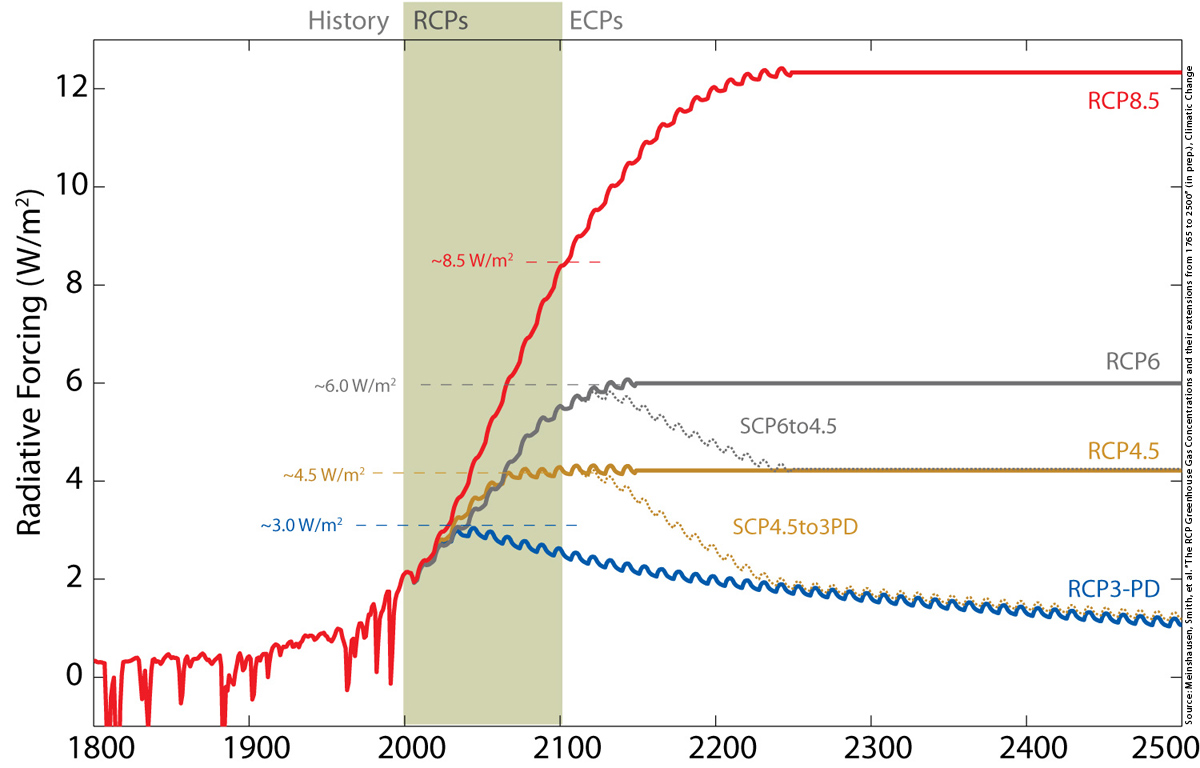

The scientists considered the ‘global warming potential’ to be the carbon dioxide equivalents emitted for each kilogram of meat produced – and found that the global warming potential (GWP) of lab-based meat using these purified media is up to 25 times greater than the average for retail beef.

The study is Environmental impacts of cultured meat: A cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment Derrick Risner et al. (UC Davis) 2023. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

Abstract

Interest in animal cell-based meat (ACBM) or cultured meat as a viable environmentally conscious replacement for livestock production has been increasing, however a life cycle assessment for the current production methods of ACBM has not been conducted.

Currently, ACBM products are being produced at a small scale and at an economic loss, however ACBM companies are intending to industrialize and scale-up production. This study assesses the potential environmental impact of near term ACBM production.

Updated findings from recent technoeconomic assessments (TEAs) of ACBM and a life cycle assessment of Essential 8™ were utilized to perform a life cycle assessment of near-term ACBM production. A scenario analysis was conducted utilizing the metabolic requirements examined in the TEAs of ACBM and a purification factor from the Essential 8™ life cycle assessment was utilized to account for growth medium component processing.

The results indicate that the environmental impact of near-term ACBM production

is likely to be orders of magnitude higher than median beef production

if a highly refined growth medium is utilized for ACBM production.

Figure 1 is a process flow diagram of a fed-batch ACBM production system with associated energy requirements.

Lifecycle Impact assessment (LCIA)

After all the inputs were identified and consolidated, a life cycle impact assessment was completed utilizing data and methods from the E8 LCA, OpenLCA v.1.10 software and OpenLCA LCIA v2.1.2 methods software. The tool for reduction and assessment of chemicals and other environmental impacts (TRACI) 2.1 was the LCIA methods utilized in the OpenLCA LCIA software, and these results were combined with the facility power data to determine the potential environmental impact of the production of 1 kg ACBM (wet basis).

Scenario analysis

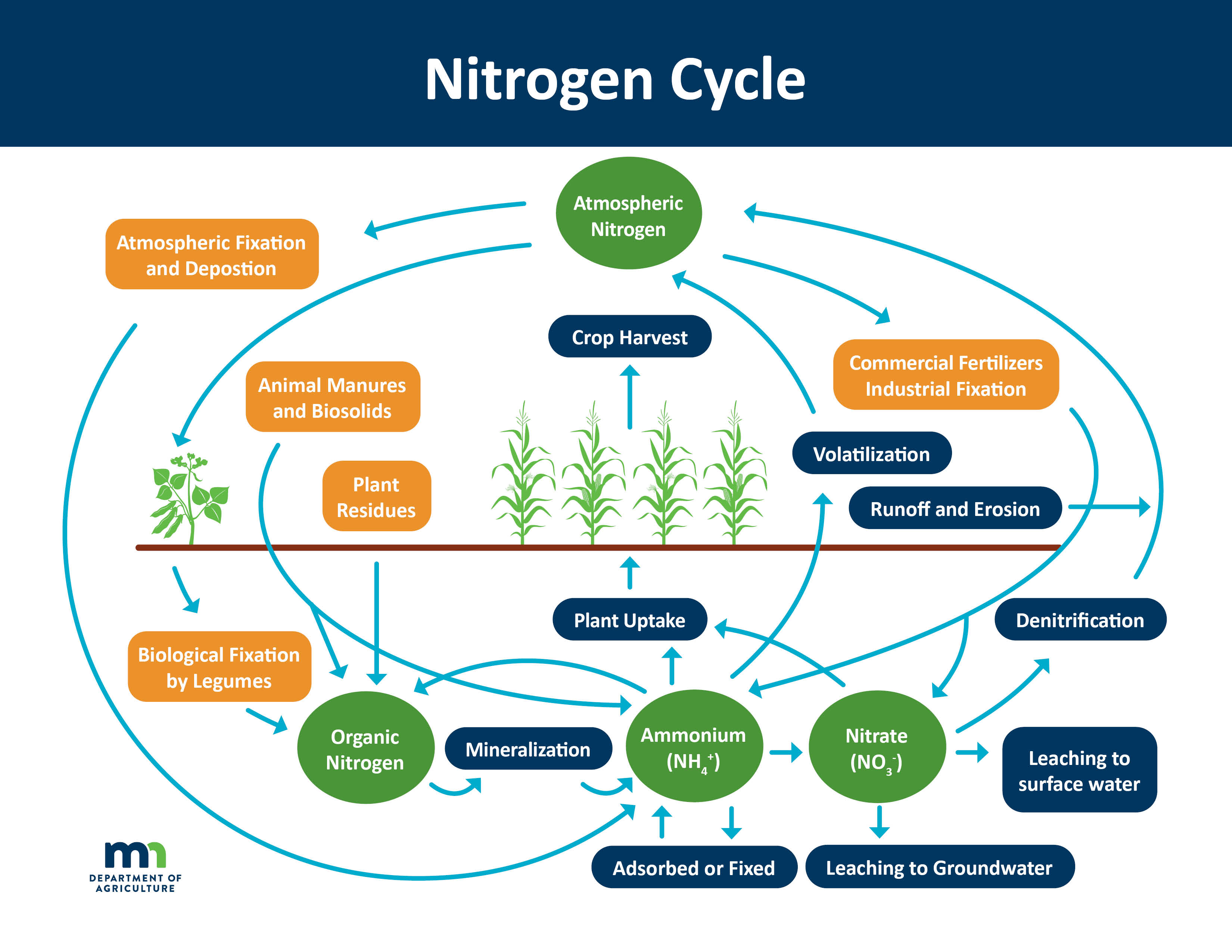

All scenarios utilize a fed-batch system as described in the Humbird (2021) TEA. Energy estimates from the Humbird TEA are utilized in all scenarios. Growth medium components were assumed to be delivered to the animal cells as needed and the build-up of growth inhibiting metabolites such as lactate or ammonia are not accounted for unless specifically stated in the scenario. The growth medium substrates are also assumed to be supplied via fed batch to achieve the highest possible specific growth rate in the production bioreactor. The three minimum/base scenarios were defined utilizing data from the Risner et al. and Humbird TEAs then a purification factor was applied based on the results from a LCA which examined the environmental impact of fine chemical and pharmaceutical production (Wernet et al., 2010).

Each of the three base scenarios were examined independently and then

with the purification factor applied for a total of six scenarios in the assessment.

Results

The LCIA was conducted on both the base scenarios and scenarios with purified growth medium components. The GWP for all ACBM scenarios (19.2 to 1,508 kg of CO2e per kilogram of ACBM) was greater than the minimum reported GWP for retail beef (9.6 kg of CO2e per kg of FBFMO) (Poore & Nemecek, 2018). The GWP of all purified scenarios ranged from 246 to 1,508 kg of CO2e per kilogram of ACBM which is 4 to 25 times greater than the median GWP of retail beef (∼60 kg CO2e per kg of FFBMO). Without purification of the growth medium components, the GWP of the GCR scenario is approximately 25% greater than reported median of GWP of retail beef (Poore & Nemecek, 2018).

It should be noted that the system boundary of this LCA stops at the ACBM production facility gate and does not include product losses, cold storage, transportation, and other environmental impacts associated with the retail sale of beef. Inclusion of these post-production processes would increase the GWP of ACBM products.

Figure 3 illustrates the difference in the GWP of retail beef and cradle to upstream ACBM production gate.

Discussion

Our results indicate that ACBM is likely to be more resource intensive than most meat production systems according to this analysis. In this evaluation, our primary focus has been on the resource intensity of the growth mediums. We have largely focused on the quantity of growth medium components (e.g. glucose, amino acids, vitamins, growth factors, salts, and minerals) and attempted to account for purification requirement of those components for animal cell culture. We also acknowledge that our analysis may be viewed as minimum environmental impacts due to several factors including incomplete datasets, the exclusion of energy and materials required to scale the ACBM industry and exclusion of the energy and materials needed to scale industries which would support ACBM production.

Animal cell culture is inherently different than culturing bacteria or yeast cells due to their enhanced sensitivity to environmental factors, chemical and microbial contamination. This can be illustrated by the industrial shift to single use bioreactors for monoclonal antibody production to reduce costs associated with contamination (Jacquemart et al., 2016). Animal cell growth mediums have historically utilized fetal bovine serum (FBS) which contains a variety of hormones and growth factors (Jochems et al., 2002). Serum is blood with the cells, platelets and clotting factors removed. Processing of FBS to be utilized for animal cell culture is an 18-step process that is resource intensive due to the level of refinement required for animal cell culture.

Thus, the authors believe that commercial production of an ACBM product utilizing

FBS or any other animal product to be highly unlikely given this high level of refinement.

Conclusion

Critical assessment of the environmental impact of emerging technologies is a relatively new concept, but it is highly important when changes to societal-level production systems are being proposed (Bergerson et al., 2020). Agricultural and food production systems are central to feeding a growing global population and the development of technology which enhances food production is important for societal progress. Evaluation of these potentially disruptive technologies from a systems-level perspective is essential for those seeking to transform our food system. Ideally, systems-level evaluations of proposed novel food technologies will allow policymakers to make informed decisions on the allocation of government capital. Proponents of ACBM have hailed it as an environmental solution that addresses many of the environmental impacts associated with traditional meat production.

Upon examination of this highly engineered system, ACBM production appears

to be resource intensive when examined from the cradle to production gate

perspective for the scenarios and assumptions utilized in our analyses.

Our environmental assessment is grounded in the most detailed process systems available that represent current state-of-the-art in this emerging food technology sector. Our model generally contradicts previous studies by suggesting that the environmental impact of cultured meat is likely to be higher than conventional beef systems, as opposed to more environmentally friendly. This is an important conclusion given that investment dollars have specifically been allocated to this sector with the thesis that this product will be more environmentally friendly than beef.

In sum, understanding the minimum environmental impact of near term ACBM is highly important for governments and businesses seeking to allocate capital that can generate both economic and environmental benefits (Zimberoff, 2022). We acknowledge that our findings would likely be the minimum environmental impact due to the preliminary nature of our LCA. This LCA aims to be as transparent as possible to allow the interested parties to understand our logic and why we have developed these conclusions. We also hope that our LCA will provide evidence of the need for additional critical environmental examination of new food and agriculture technologies.

Bottom Line:

“Our findings suggest that cultured meat is not inherently better for the environment than conventional beef. It’s not a panacea,” said corresponding author Edward Spang, an associate professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology. “It’s possible we could reduce its environmental impact in the future, but it will require significant technical advancement to simultaneously increase the performance and decrease the cost of the cell culture media.”

Even the most efficient beef production systems reviewed in the study outperform

cultured meat across all scenarios (both food and pharma), suggesting that

investments to advance more climate-friendly beef production may yield

greater reductions in emissions more quickly than investments in cultured meat.