Coercive Environmentalism

Gus Van Horn writes at Real Clear Markets The Recycling Crowd Embraces Grade-School Juvenility. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Gus Van Horn writes at Real Clear Markets The Recycling Crowd Embraces Grade-School Juvenility. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

The third-grade boy shamefully completed his apology, in front of first grade. I was luckier than I felt. Just that morning, I had been convinced that the way to win friends was to do what the popular kids did: Stomp on the first-grader’s coffee-can art project. I knew this was wrong but I immediately impressed the popular crowd — the wrong way. My swift punishment only reinforced what I already knew: A crowd was a poor substitute for my own judgment. This lesson has served me well throughout my life, yet I was surprised to find myself transported back to that classroom by a New York Times video — about recycling, of all things. A connection jolted me when I viewed “The Great Recycling Con:”

The captains of industry were making the same mistake I had but with a twist: They are stomping on their own cans.

I remember the early days of residential recycling as clearly as that hug. At first, only the neighborhood crank went through the trouble. But, after about a decade of shaming by celebrities and over-hyping of stories — like the long search of a garbage scow for a customer — governments got involved. Seemingly overnight, nearly everyone was being forced to recycle or taxed to support it. Companies had marching orders to label products so we could comply. The details of these orders were minute to the point of confusion. This point can be gleaned from the video, but get a load of this subtitle: “The greatest trick corporations ever played was making us think we could recycle their products.”

I’m disappointed that corporations had voiced so much support for recycling, but they hardly deserve the blame for labeling laws.

Reaction to proposed Vermont law requiring clear plastic trash bags.

But this has been the MO of the left since the industrial revolution. Regarding 1800’s railroads, Ayn Rand noted:

[W]hat could the railroads do, except try to “own whole legislatures,” if these legislatures held the power of life or death over them? What could the railroads do, except resort to bribery, if they wished to exist at all?

Who was to blame and who was “corrupt”–the businessmen who had to pay “protection money” for the right to remain in business–or the politicians who held the power to sell that right?

The railroads played a game they should have opposed — only to end up blamed for a situation they didn’t create. (To the degree they saw this as an acceptable way to win market share, they share the blame.) We see this today with companies bullied into removing harmless ingredients, such as nitrites from food, or parabens from cosmetics, under the perverse twin incentives of fashionable panic and fear of competition.

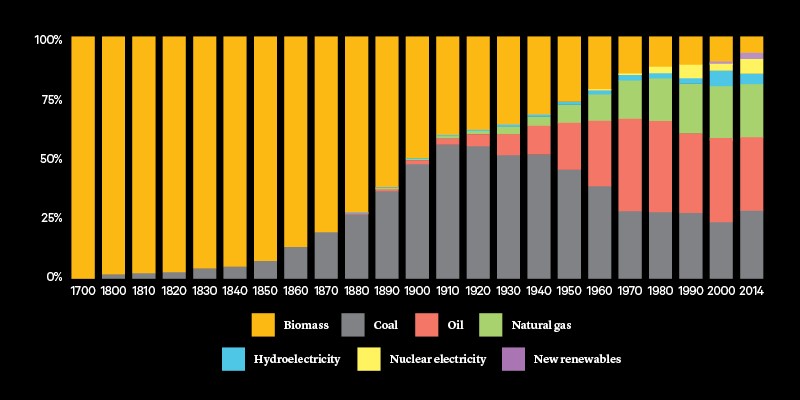

The worst case involves the fossil fuel industry, which is vital to our lives and prosperity – while under constant and intense pressure from environmentalists. Energy advocate Alex Epstein notes:

The industry never explained the value of energy and why fossil fuels are superior sources of energy. In fact, the industry is constantly out there saying, “We’re not against wind and solar, we’re for all of the above, we’re in the middle of an energy transition,” etc. That’s why I always stress when I talk to people (a) that low cost, reliable energy is indispensable to human flourishing and (b) that the fossil fuel industry is uniquely good at creating it. People need both of those points.

Epstein is right: Companies should stop fearing the cool media kids scaremongering and start reminding the people who count – their customers — of the full value they offer.

When I think about that day in school, I wish I could go back and tell that third-grader that real friends don’t tempt people to ignore their own judgment; and that he already had good friends, because he had a lot to offer. The same goes for countless productive individuals in whole industries that our media routinely paint as evil ahead of our politicians taking yet more control. Our industry captains have gone along with this for far too long. Rather than accepting these scurrilous attacks, they should view them as personal insults. A great way to begin to fight back is to remind people of the enormous good they and their employees create.

Who’s the bully? Who’s the victim?

Previous Post: On Coercive Climatism: Writings of Bruce Pardy

Many people have heard of Jordan Peterson due to his battles against post modernism and progressive social justice warfare. Bruce Pardy is another outspoken Canadian professor, whose latest statement was posted at the National Post, H/T GWPF.

Many people have heard of Jordan Peterson due to his battles against post modernism and progressive social justice warfare. Bruce Pardy is another outspoken Canadian professor, whose latest statement was posted at the National Post, H/T GWPF.

Let the Paris climate deal die. It was never good for anything, anyway

Opinion: Paris is a climate fairy tale. It has always been more about money and politics than the environment. Excerpts below with my bolds.

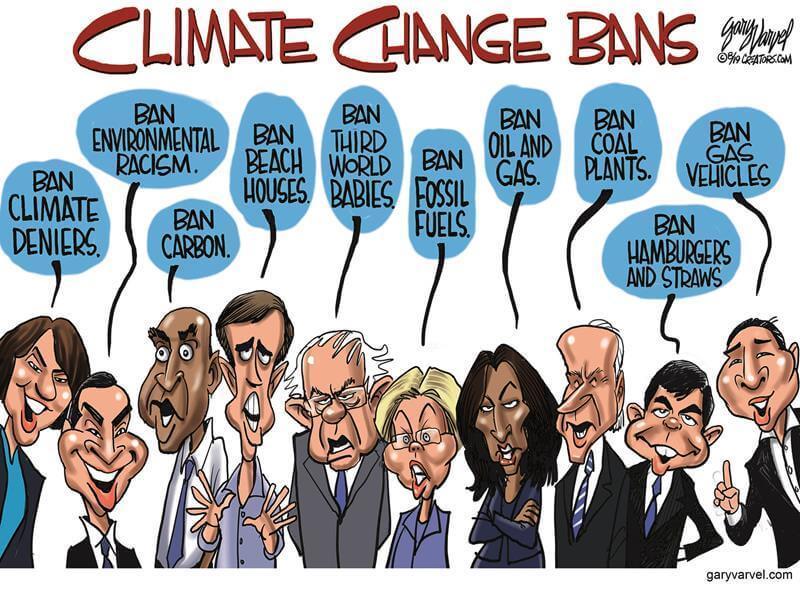

Paris is more a movement than a legal framework. It imagines the world as a global community working in solidarity on a common problem, making sacrifices in the common good, reducing inequality and transcending the negative effects of market forces. In this fable, climate change is a catalyst for revolution. It is the monster created by capitalism that will turn on its creator and bring the market system to the end of its natural life. A new social order will emerge in which market value no longer determines economic decisions. Governments will exercise influence over economic behaviour by imposing “market-based mechanisms” such as carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems. Enlightened leaders will direct energy use based upon social justice values and community needs. An international culture will unite peoples in a cause that transcends their national interests, giving way to the next stage of human society. Between the lines of the formal text, the Paris agreement reads like a socialist nightmare.

The regime attempts to establish an escalating global norm that requires continual updating, planning and negotiation. To adhere, governments are to supervise, regulate and tax the energy use and behaviour of their citizens (for example, the Trudeau government’s insistence that all provinces impose a carbon tax or the equivalent, to escalate over time.) Yet for all of the domestic action it legitimizes, Paris does not actually require it. Like the US$100-billion pledge, reduction targets are outside the formal Paris agreement. They are voluntary; neither binding nor enforceable. Other countries have condemned Trump’s withdrawal and reaffirmed their commitment to Paris but many of them, including Canada, are not on track to meet even their initial promises. Global emissions are rising again.

If human action is not causing the climate to change, Paris is irrelevant. If it is, then Paris is an obstacle to actual solutions. If there is a crisis, it will be solved when someone develops a low-carbon energy source as useful and cheap as fossil fuels. A transition will then occur without government interventions and international declarations. Until then, Paris will fix nothing. It serves interests that have little to do with atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. Will America’s repudiation result in its eventual demise? One can hope.

Bruce Pardy belongs to the Faculty of Law, Queen’s College, Kingston, Ontario. This post will provide excerpts from several of Pardy’s writings to give readers access to his worldview and its usefulness making sense of current socio-political actions.

In 2009 Pardy wrote Climate Change Charades: False Environmental Pretences of Statist Energy Governance

The Abstract:

Climate change is a poor justification for energy statism, which consists of centralized government administration of energy supplies, sources, prices, generating facilities, production and conservation. Statist energy governance produces climate change charades: government actions taken in the name of climate change that bear little relationship to the nature of the problem. Such actions include incremental, unilateral steps to reduce domestic carbon emissions to arbitrary levels, and attempts to choose winners and losers in future technology, using public money to subsidize ineffective investments. These proffered solutions are counter-productive. Governments abdicate their responsibility to govern energy in a manner that is consistent with domestic legal norms and competitive markets, and make the development of environmental solutions less likely rather than more so.

Pardy also spoke out in support of Peterson and against the Canadian government legislation proscribing private speech between individuals. His article in National Post was Meet the new ‘human rights’ — where you are forced by law to use ‘reasonable’ pronouns

Human rights were conceived to liberate. They protected people from an oppressive state. Their purpose was to prevent arbitrary arrest and detention, torture, and censorship, by placing restraints on government. The state’s capacity to accommodate these “negative rights” was unlimited, since they required only that people be left alone.

If only arm twisting were prohbited beyond the ring.

But freedom from interference is so 20th century. Modern human rights entitle. We are in the middle of a culture war, and human rights have become a weapon to normalize social justice values and to delegitimize competing beliefs. These rights are applied against other people to limit their liberties.

Freedom of expression is a traditional, negative human right. When the state manages expression, it threatens to control what we think. Forced speech is the most extreme infringement of free speech. It puts words in the mouths of citizens and threatens to punish them if they do not comply. When speech is merely restricted, you can at least keep your thoughts to yourself. Compelled speech makes people say things with which they disagree.

Some senators expressed the view that forcing the use of non-gendered pronouns was reasonable because calling someone by their preferred pronoun is a reasonable thing to do. That position reflects a profound misunderstanding of the role of expression in a free society. The question is not whether required speech is “reasonable” speech. If a statute required people to say “hello,” “please” and “thank you,” that statute would be tyrannical, not because “hello,” “please” and “thank you” aren’t reasonable things to say, but because the state has dictated the content of private conversation.

Traditional negative human rights give people the freedom to portray themselves as they wish without fearing violence or retribution from others. Everyone can exercise such rights without limiting the rights of others. Not so the new human rights. Did you expect to decide your own words and attitudes? If so, human rights are not your friend.

These positions derive from bedrock reasoning by Pardy on the foundations of law and legitimacy. An insight into his thinking is his rebuttal of a critic The Only Legitimate Rule: A Reply to MacLean’s Critique of Ecolawgic Dalhousie Law Journal, Spring 2017

Ecosystem as One model of Society

An ecosystem is not a thing. It does not exist as a concrete entity. “Ecosystem” is a label for the dynamics that result when organisms interact with each other and their environment. Those dynamics occur in infinite variation, but always reflect the same logic:

Competition for scarce resources leads to natural selection, where those organisms better adapted to ecosystem conditions survive and reproduce, leading to evolutionary change. All participants are equally subject to their forces; systems do not play favourites.

In ecosystems, the use of the word “autonomy” does not mean legally enforced liberty but the reverse: no externally imposed rules govern behaviour. In ecosystems unmanaged by people, organisms can succeed or fail, live or die, as their genetically determined physiology and behaviour allow. Every life feeds on the death of others, whether animal or plant, and those better adapted to their circumstances survive to reproduce. Organisms can do anything that their genes dictate, and their success or failure is the consequence that fuels evolution.

When an antelope is chased by a lion and plunges into a river to escape, that action allows the antelope to survive and thus to reproduce. The offspring may carry a genetic disposition to run into water when chased by predators. There are no committees of either antelopes or humans deciding how antelopes will behave. Autonomy in ecosystems is not a human creation. It is not based upon human history or culture and is not a human preference.

Market as a Different Model of Society

A market is not a thing either. Nor is it a place. Markets, like ecosystems, do not exist as concrete entities. “Market” is a label for the dynamics that result when people exchange with each other. Bargains may be commercial in nature, where things are bought and sold, but they also occur in other facets of life. For example, in Ecolawgic I suggested that marriage is a kind of exchange that is made when people perceive themselves better off to enter into the bargain than not to.

As I said in Ecolawgic, “Laws and governments can make markets more stable and efficient, such as by enforcing contracts and creating a supply of money, but they create neither the activity of trading nor the market dynamics that the transactions create.” A market is not a place or a legal structure but the dynamics of a collection of transactions. It does not exist before or independently of the transactions within it. The transactions make the market. Transactions are not created by governments but by the parties who enter into them.

People transact whether they are facilitated by governments or not. The evidence is everywhere. If it were not so, human beings would not have bartered long before there were governments to create money and enforce contracts. During Prohibition, no alcohol would have been produced and sold. Citizens of the Soviet Union would not have exchanged goods. Today there would be no drug trade, no black market and no smuggling. Cigarettes would not be used as currency inside jails. People would not date, hold garage sales or trade hockey cards. There would be no Bitcoin or barter. Try prohibiting people from transacting and see that they will transact anyway. They will do so because they perceive themselves as better off. Sometimes the benefit is concrete and sometimes it is ethereal. The perception of benefit is personal and subjective.

Ecosystems are Coercive, Markets are Voluntary

Ecosystems and markets share many features but they differ in one important respect. Violence plays an important role in ecosystems but is not a part of voluntary market exchange. Ecosystems are arenas for mortal combat. Lions eat antelopes if they can catch them. Nothing prevents taking a dead antelope from a lion except the lion’s response. There are no restrictions on survival strategies, and organisms do not respect the interests, habitats or lives of other organisms.

Markets, in contrast, proceed upon the judgment of the transacting parties that they are better off to trade than to fight. The hunter did not shoot the woodworker to get chairs, and the woodworker traded for meat instead of stealing it. They chose to trade because it made them better off than fighting. The reasons are their own. Perhaps they were friends, colleagues or allies. Perhaps they believed that harming other people is wrong. Perhaps they hoped to have an ongoing trading relationship. Perhaps fighting carried risks that were too high and they feared injury or retribution. Perhaps trading was less work than fighting.

For whatever reason, they chose to trade. This choice is not universal. People have traded throughout human history, but they have also fought. I do not maintain that trading is any more “natural” or inbred than fighting, but neither is it is less so. When people choose to fight, they are no longer part of a market. Markets are like ecosystems with the violence removed. They are the kinder, gentler version of ecosystems.

There are only two models for legal governance and only one legitimate rule.

The logic is as follows:

1. In the wild, organisms compete for scarce resources. Those organisms better adapted to conditions survive and reproduce. Their interactions constitute ecosystems. No legal rules govern behaviour and might is right.

2. Human beings trade spontaneously. Parties enter into transactions when they perceive themselves as better off to trade than to fight. Their transactions constitute markets.

3. Moral values and policy goals are preferences whose inherent validity cannot be established. They are turtles all the way down. Therefore laws based upon those preferences lack legitimacy.

4. When governments use might to impose laws and policies that are illegitimate, they unintentionally imitate ecosystems, where might is right. Political constituencies use whatever means necessary to impose their preferences, and their opponents use whatever means necessary to resist. They are “autonomous” in the ecosystem sense: there are no inherently valid restrictions on behaviour. The result is a social order of division and conflict.

5. The alternative is to model human governance on the other system that exists independently of state preference: markets. If the model for human governance is markets, interactions between people are voluntary. People are “autonomous” in the market sense: they may pursue their own interests without coercion. Instead of imposing illegitimate rules and policies, the state uses force only to prohibit people from imposing force on each other. A plethora of sub-rules follow as corollaries of the rule against coercion: property, consent, criminal offences that punish violence and so on.

6. There is no third choice. Coercion is not right or wrong depending upon the goals being pursued since those goals are merely preferences. Their advocates cannot establish that their goals have inherent validity to those who do not agree. Therefore, giving priority to those objectives is to assert that might is right. If might is right, we are back to ecosystems, where any and all actions are legitimate.

7. If might is right, anything goes, and the model is ecosystems. If might is not right, force is prohibited, and the model is markets. Choose one and all else follows.

When I claim that a prohibition on force is the only legitimate rule, I mean the only substantive rule to govern relations between competent adults. No doubt the administration of a legal system, even a minimalist one, would require other kinds of laws to function. Constitutional rules, court administration, the conduct of elections and procedures to bring legal proceedings are a few of the other categories that would be necessary in order to give effect to the general rule.

No Property, No Market

But the existence of property rights must follow from a general rule prohibiting coercion. If it does not, the general rule is not what it purports to be. When people trade, they recognize the property interest held by the other party. It is that interest that they wish to obtain. When the woodworker trades chairs for the hunter’s meat, she trades “her” chairs for “his” meat. The trade would not occur without a mutual understanding of the possession that both hold over their respective stuff.

Sometimes those interests are recognized and protected by the law, which according to Bentham created the property. However, since markets arise even where no property is legally recognized, the notion of property must be prior to the law. Above I gave examples of markets that have arisen where no legal regime has protected property rights: prehistorical trade, alcohol sales during Prohibition, black markets in the Soviet Union, the modern day drug trade, smuggling of illicit goods, and the internal markets of prisons. Since trading occurs even in the absence of an approving legal regime, the notion of property must exist independently as well.

No Consent, No Market

Autonomy in the market sense means to be able to pursue your own interests and control your own choices without coercion. Consent is part and parcel of autonomy. Without the ability to consent, no trades can be made. Without trades, no markets exist. If one cannot consent to be touched, to give up property, to make bargains, to mate, to arm wrestle, to trade chairs for meat, to sell labour for money, and so on, then one is not autonomous.

If force is prohibited, then corollaries are laws that protect people from having force imposed upon them. Laws apply the force of the state to prevent or punish the application of force. A criminal law that prohibits assault is an extension of the general rule. A tax to finance the police department is legitimate if its purpose is to investigate and prosecute violent crimes. Traffic laws prevent people from running each other over. Civil liability compensates for physical injuries caused by the force of others.

Illegitimate Laws, No Market

Illegitimate laws use state coercion to seek other ends such as enforcing moral standards, pursuing social goals or saving people from themselves. A criminal law that prohibits the use of drugs uses state force to prevent an activity in which there is no coercion. A tax to fund the armed forces to protect the peace may be legitimate, but one to take wealth from Peter to give to Paul is not. The legal regimes of modern administrative states consist largely of instrumentalist laws and policies that are inconsistent with the general rule, including tax laws, economic development programs, bankruptcy, patent regimes, mandatory government-run pension plans and MacLean’s version of environmental regulation, in which each decision turns on a political determination of the values to be applied.

It is either ecosystems or markets. Either might is right or it is not. If it is, then human society is subject to the law of the jungle where people are at liberty to fight like animals if they choose to do so. If it is not, then human society is a marketplace where people may enter into transactions voluntarily and the state may justifiably use force only to prevent or punish the application of force.

There is no third choice. Some might insist that coercion is not categorically wrong but that it can be right or wrong depending upon the other goals to be pursued. Those goals are merely preferences. They are turtles all the way down. I do not maintain that other rules will not be passed and enforced using the established machinery of government but only that they have no claim to legitimacy, any more than other rules that might have been chosen instead. If force is used to pursue those preferences, why would others not use force to resist? Such a choice results in a free-for-all. If state force is right only because it cannot be resisted, that means that might is right. The administrative welfare state prevails not because it is justified morally or socially but because it has managed to secure a monopoly on violence. The imposition of government preferences is an invitation to those opposed to an arbitrary policy agenda to take up force against it.

Summary

In a way, Pardy is warning us not to take for granted the free market social democracies to which we were accustomed. Post modern progressive social justice warriors have decided that society is essentially an endless power struggle, that one group’s rights are gained only at the expense of another group. In other words, it’s a dog-eat-dog, might makes right ecosystem. Pardy says there is another way, which has been the basis for the rise of civilization, but can be reversed by governance that destroys the free market of ideas and efforts by imposing values favored by the rich and powerful.

Footnote about Turtles. Pardy explains the metaphor:

In Rapanos v. United States, Justice Antonin Scalia offered a version of the traditional tale of how the Earth is carried on the backs of animals. In this version of the story, an Eastern guru affirms that the earth is supported on the back of a tiger. When asked what supports the tiger, he says it stands upon an elephant; and when asked what supports the elephant he says it is a giant turtle. When asked, finally, what supports the giant turtle, he is briefly taken aback, but quickly replies “Ah, after that it is turtles all the way down.”

Climate Litigation Watch is reporting the ruling by Judge Barry Ostrager ending the case brought by NYAG Leticia James against ExxonMobil. The loss could hardly be more complete. The full text of the ruling is

Climate Litigation Watch is reporting the ruling by Judge Barry Ostrager ending the case brought by NYAG Leticia James against ExxonMobil. The loss could hardly be more complete. The full text of the ruling is

Just Say No!

Just Say No!