Climate on Ice: Ocean-Ice Dynamics

Update May 30, 2015 Longer term context by E.M. Smith added below

Sea ice is not simple. Some Background is in order.

When white men started to explore the north of America, they first encountered the Crees. Hudson Bay posts were established to trade goods for pelts, especially the beavers used for making those top hats worn by every gentleman of the day.

The Crees told the whites that further on toward the Arctic Circle there were others they called “eskimos”. The Cree word means “eaters of raw meat” and it is derogatory. The Inuit (as they call themselves) were found to have dozens of words for snow, a necessary vocabulary for surviving in the Arctic world.

A recent lexicon of sea ice terminology in Nunavik (Appendix A of the collective work Siku: Knowing our Ice, 2008) comprises no fewer than 93 different words. These include general appellations such as siku, but also terms as specialized as qautsaulittuq, ice that breaks after its strength has been tested with a harpoon; kiviniq, a depression in shore ice caused by the weight of the water that passed over and accumulated on its surface during the tide; or iniruvik, ice that cracked because of tide changes and that the cold weather refroze.

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuit-words-for-snow-and-ice/

With such complexity of ice conditions, we must recognize that any general understanding of ocean-ice dynamics will not be descriptive of all micro-scale effects on local or regional circumstances.

Short Term Sea Ice Freezing and Melting Cycle

Alarmists only mention positive feedbacks from ice melting, so one is left to wonder why there is any Arctic ice left so many years since the Little Ice Age ended around 1850. Actually there are both positive and negative feedbacks, with one or the other dominating at different times and places.

Of course, the basic cycle is the seasonality of sunless winters and sunlit summers.

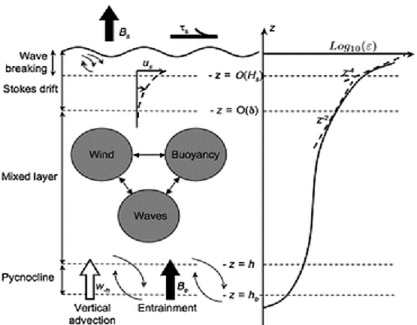

Remember that ice grows because of a transfer of heat from the relatively warm ocean to the cold air above. Also remember that ice insulates the ocean from the atmosphere and inhibits this heat transfer. The amount of insulation depends on the thickness of the ice; thicker ice allows less heat transfer. If the ice becomes thick enough that no heat from the ocean can be conducted through the ice, then ice stops growing. This is called the thermodynamic equilibrium thickness. It may take several years of growth and melt for ice to reach the equilibrium thickness. In the Arctic, the thermodynamic equilibrium thickness of sea ice is approximately 3 meters (9 feet). However, dynamics can yield sea ice thicknesses of 10 meters (30 feet) or more. Equilibrium thickness of sea ice is much lower in Antarctica, typically ranging from 1 to 2 meters (3 to 6 feet).

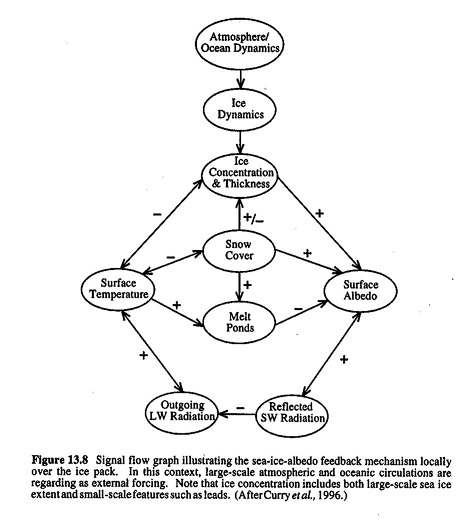

Snow has an even higher albedo than sea ice, and so thick sea ice covered with snow reflects as much as 90 percent of the incoming solar radiation. This serves to insulate the sea ice, maintaining cold temperatures and delaying ice melt in the summer. After the snow does begin to melt, and because shallow melt ponds have an albedo of approximately 0.2 to 0.4, the surface albedo drops to about 0.75. As melt ponds grow and deepen, the surface albedo can drop to 0.15. As a result, melt ponds are associated with higher energy absorption and a more rapid ice melt.

https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/seaice/processes/growth_melt_cycle.html

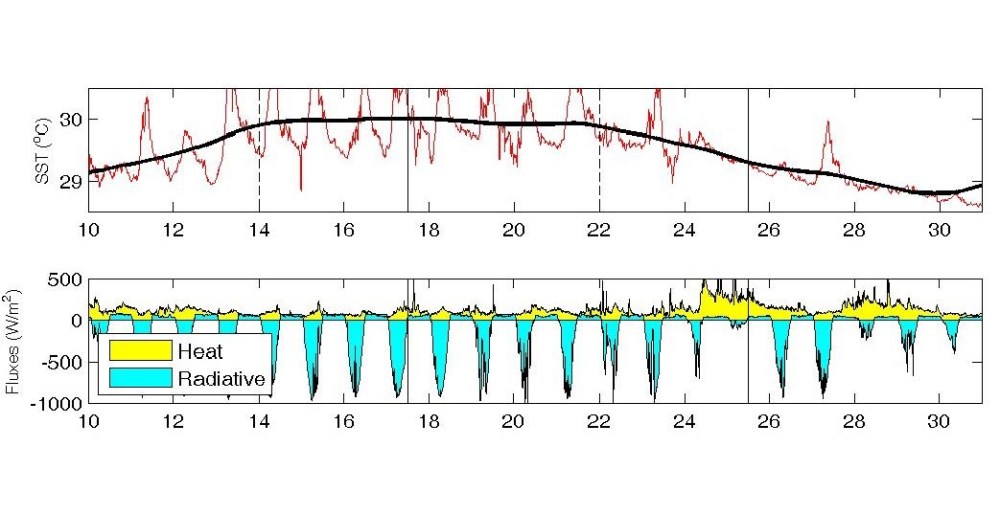

The short-term dynamics of sea ice freezing and melting can be summarized in this diagram from Dr. Judith Curry:

Dr. Curry has written extensively on sea ice, and an introduction to her sources is here:

http://judithcurry.com/2014/10/15/new-presentations-on-sea-ice/

Decadal Variability in Sea Ice Extent

Medium term sea ice variations are well described by Lawrence A. Mysak and Silvia A. Venegas of the Centre for Climate and Global Change Research and Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic

Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

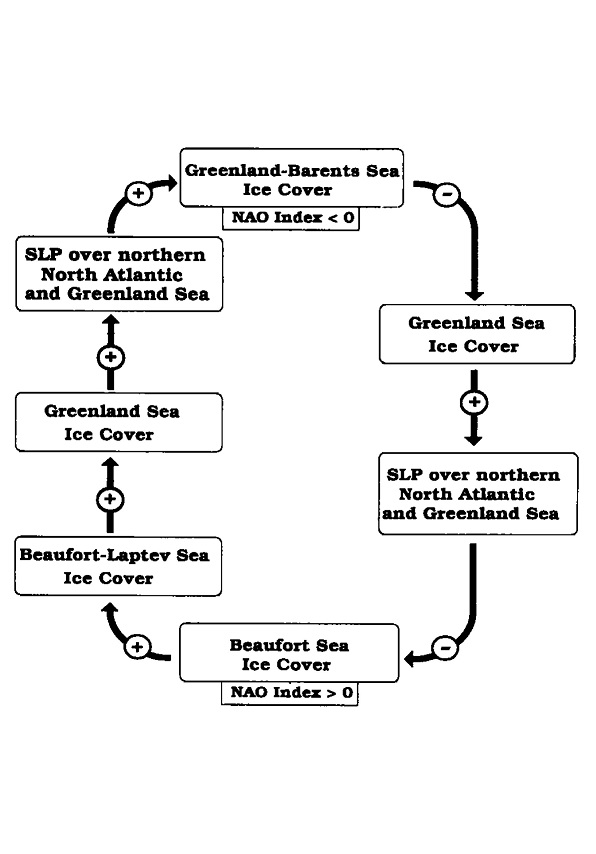

Abstract: A combined complex empirical orthogonal function analysis of 40 years of annual sea ice concentration (SIC) and winter sea level pressure (SLP) data reveals the existence of an approximately 10-year climate cycle in the Arctic and subarctic.

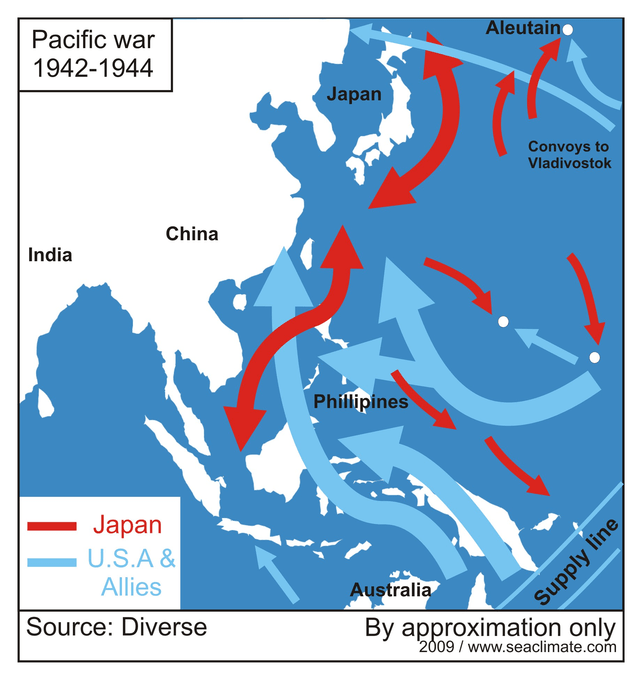

“Starting at the top of the loop in Figure 4, we propose that large SIC (Sea Ice Concentration) positive anomalies are created in the Greenland Sea by a combination of anomalous northerly winds and a relatively small northward transport of warm air (sensible heat) [Higuchi et al., 1991] associated with a negative NAO pattern. The relationship between severe sea ice conditions in the Greenland Sea and a weak atmospheric circulation (negative NAO) was previously noticed by Power and Mysak [1992]. Over the Barents Sea, on the other hand, the formation of the large positive SIC anomalies may be mainly due to weaker-than-normal advection of warm water by the northward branch of the North Atlantic Current when the NAO index is negative (R. R. Dickson, pets.comm., 1998).”

“These SIC anomalies are then advected into the Labrador Sea by the local mean ocean circulation over a 3-4 year period. When the southern part of the Greenland Sea thus becomes relatively ice free (as implied by the minus sign at the upper-right corner of the loop), strong heating of the atmosphere during winter occurs, which is hypothesized to cause the Icelandic Low to deepen at that time (hence the plus sign on the right-hand side of the loop). This may help change the polarity of the NAO. When the NAO index is positive (deep Icelandic Low), the wind anomalies create positive SIC anomalies in the Beaufort Sea (see bottom of the loop), which are then slowly advected out of the Arctic via the Beaufort Gyre and Transpolar Drift Stream over a 3-4 year period (see lower-left corner and left-hand side of loop).”

“As a consequence, the Greenland Sea becomes extensively ice covered, which suddenly cuts off the heat flux to the atmosphere during winter and hence is likely to cause the Icelandic Low to weaken at that time, which may contribute to changing the NAO polarity. This brings us back to the beginning of the cycle (top of Figure 4) after about 10 years.”

Click to access paper_ice_Mysak1998.pdf

Multi-Decadal Sea Ice Dynamics

In a 2005 publication Mysak presents additional empirical evidence for these ocean-ice mechanisms:

“In this paper we have shown that an intermediate complexity climate model consisting of a 3-D ocean component, a state-of-the-art sea-ice model (with elastic-viscous-plastic rheology) and an atmospheric energy-moisture balance model can successfully simulate a large number of observed changes in the Arctic Ocean and sea-ice cover during the past half-century.”

“Morison et al. (1998) found an increase in both the temperature and salinity at depths of 200–300 m in the eastern Arctic. . .This increase in salinity is also supported by the work of Steele and Boyd (1998) who found that the winter mixed layer in the Eurasian Basin had higher salinity values in the early 1990s compared with the 40-year record of the Environmental Working Group (EWG) Joint US-Russian Arctic Atlas. Morison et al. (1998) argue that the increase in salinity represents a westward advance into the Arctic of the front between the waters of the eastern and western Arctic. The aforementioned temperature and salinity changes support the hypothesis that the warm and salty Atlantic water penetrated further into the central Arctic Basin during the 1990s, and thus has pushed the front between Atlantic derived and Pacific derived waters westward.”

Click to access Mysak_et_al_2005.pdf

Summary: Sea Ice Impacts Climate Strongly, this century and beyond.

“Sea ice is a key player in the climate system, affecting local, and to some degree remote regions, via its albedo effect. Sea ice also strongly reduces air-sea heat and moisture fluxes (Ruddiman and McIntyre 1981; Gildor and Tziperman 2000), and thus may cause the air overlying it to be cooler and drier compare to air overlying ice-free ocean (Chiang and Bitz 2005). A significant part (*33 %) of the precipitation over the northern hemisphere (NH) ice sheets is believed to have originated locally from the Norwegian, Greenland and the Arctic seas (Charles et al. 1994;Colleoni et al. 2011). Lastly, sea ice affects the location of the storm track and therefore indirectly also the patterns of precipitation (e.g. Laine et al. 2009; Li and Battisti 2008).”

“Its effect on the hydrological cycle makes sea ice a potentially significant player in the temperature-precipitation feedback (Le-Treut and Ghil 1983), according to which increase in temperature intensifies the hydrological cycle and thus the snow accumulation over ice sheets. This feedback is an important part of the sea-ice switch mechanism for glacial cycles, for example Gildor and Tziperman (2000). Indeed, proxy records show drastic increase in accumulation rate during interstadial periods (Cuffey and Clow 1997; Alley et al. 1993; Lorius et al. 1979), when the sea-ice retreats from its maximal extent.”

The largest ice cap in the Eurasian Arctic – Austfonna in Svalbard – is 150 miles long with a thousand waterfalls in the summer

“We find that in a cold, glacial climate snowfall rate over the ice sheets is reduced as a result of increasing sea-ice extent (compare LGM and PDSI experiments). An increased sea-ice extent cools the climate even more, the precipitation belt is pushed southward and the hydrological cycle weakens.

We find that the albedo feedback of an extended sea-ice cover in an LGM-like climate only weakly affects the reduction of snowfall rate.

indicating that the insulating feedback is responsible for a large part of the suppression of precipitation by sea ice. It follows that the hydrological cycle is more sensitive to the insulating effect of sea ice than to its albedo. There are two reasons to the larger contribution of the insulating effect to the temperature-precipitation feedback. First, the overall cooling of the insulating effect is about twice than that of the albedo. This by itself is expected to lead to a more significant change in precipitation. In addition, the insulation effect not only reduce air-sea heat flux, it also directly prevents evaporation from ice-covered regions, which are a major source of precipitation over the NH ice sheets (Charles et al. 1994).

Click to access tziperman_sea.pdf

Conclusion: It’s the Ice and the Water

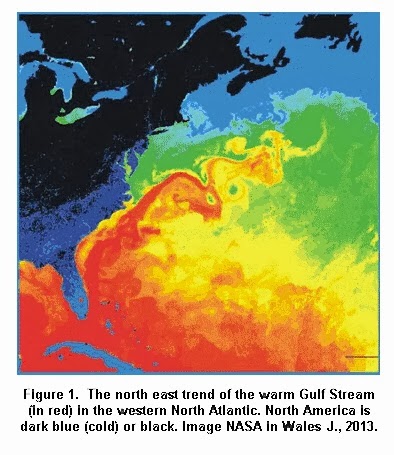

Regardless of the uncertainties in the underlying principal mechanisms of the sea ice-AMO-AMOC linkages, it is clear that multidecadal sea-ice variability is directly or indirectly related to natural fluctuations in the North Atlantic. This study provides strong, long-term evidence to support modeling results that have suggested linkages between Arctic sea ice and Atlantic multidecadal variability [Holland et al., 2001; Jungclaus et al., 2005; Mahajan et al., 2011].

Here we present observational evidence for pervasive and persistent multidecadal sea ice variability, based on time-frequency analysis of a comprehensive set of several long historical and paleoproxy sea ice records from multiple regions. Moreover, through explicit comparisons with instrumental and proxy records, we demonstrate covariability with the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO).

Click to access Gildor-Ashkenazy-Tziperman-Lev-2014.pdf

Update May 30,2015 From E.M. Smith and Salvatore Del Prete

I think I can take a crack as answering some of the questions and pointing at a likely structure for some of the other bits.

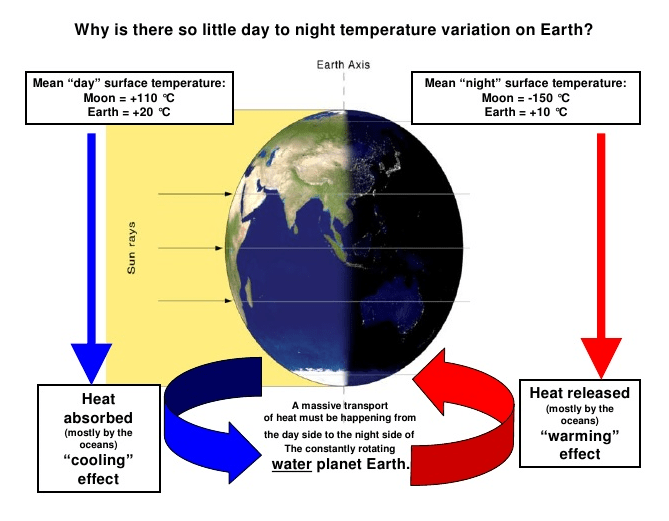

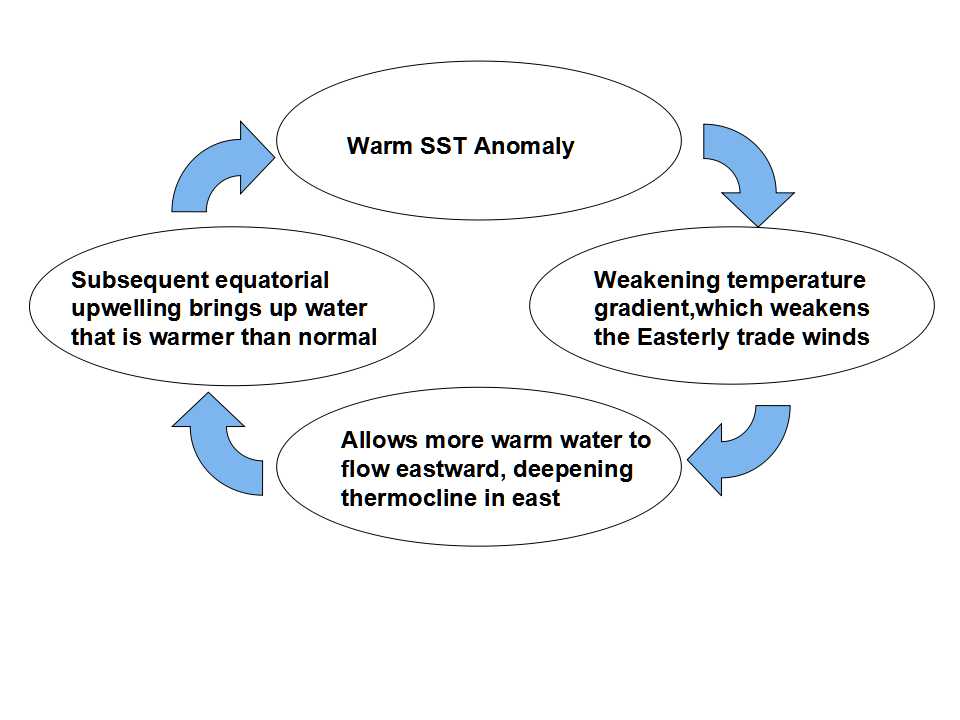

Why is it whenever the climate changes the climate does not stray indefinitely from it’s mean in either a positive or negative direction? Why or rather what ALWAYS brings the climate back toward it’s mean value ? Why does the climate never go in the same direction once it heads in that direction?

IMHO the answer is that there is a hysteresis from water that limits the excursions. On one end, freezing tends to cut down heat dumping as frozen ice does not radiate as much heat to space. On the other end, tropical storm formation limits heat in the equatorial oceans as you get more water evaporation / rise / precipitation cycles and more radiation to space from the tropopause / stratosphere. So we don’t get ‘brought back to the mean’, but rather switch from an ice ball (most of the time) to a warm & wet (10% of the time). This switching is the Malankovitch cycle, and it is driven by changes in the orbital roundness, precession of the equinox, and changes of tilt of the planet (that are not really changes of tilt, they are changes in position relative to the celestial equator.

Much more here:

https://chiefio.wordpress.com/2015/05/29/salvatore-del-prete-thesis/

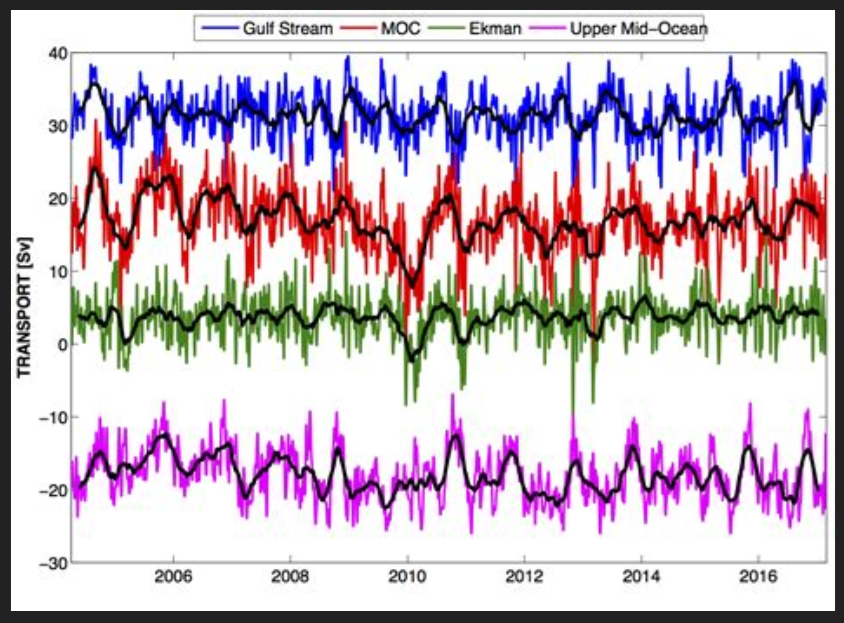

The RAPID moorings being deployed. Credit: National Oceanography Centre

The RAPID moorings being deployed. Credit: National Oceanography Centre