DOE Climate Report a Box of Surprises for the Unversed

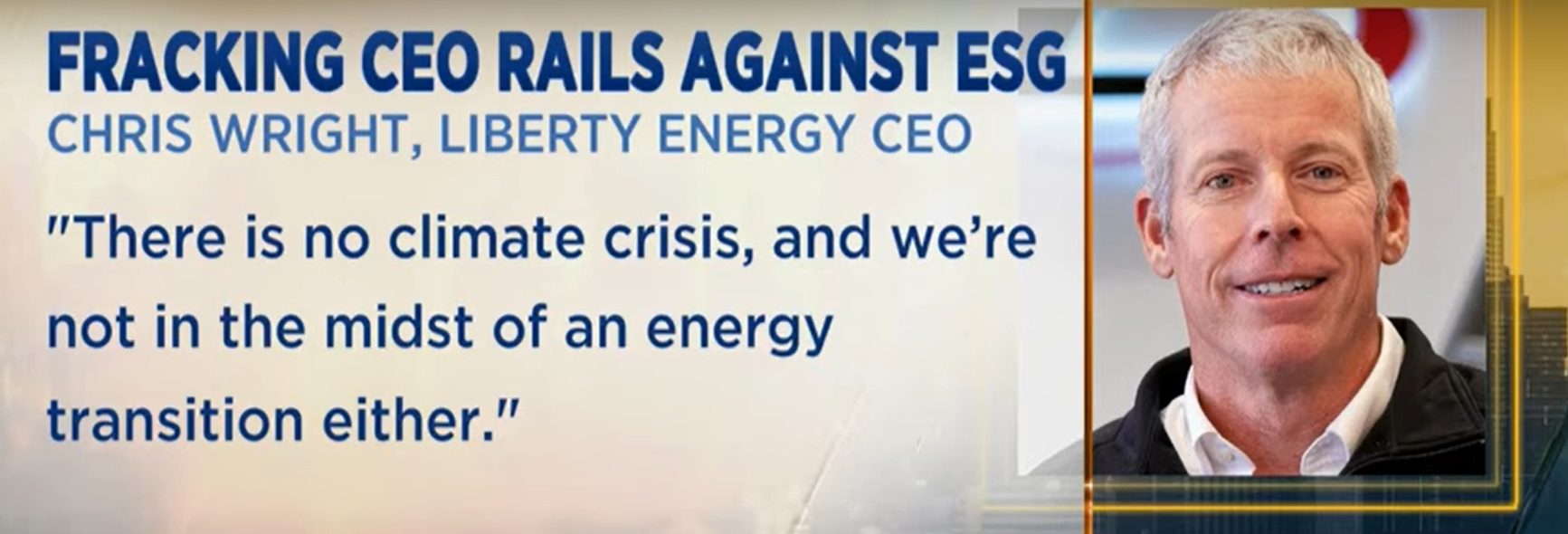

The Kim Strassel interview at WSJ is Energy Secretary Chris Wright on Resetting the Climate Debate. Below in italics is a transcript from the closed captions with my bolds and added images.

The Department of Energy’s new climate report is making waves, offering a fresh look at the alarmist claims pushed by special-interest groups and prior administrations. The report’s five scientists lay out data showing that while climate change is real, it isn’t the threat suggested by media or the climate lobby. On this episode of All Things, Energy Secretary Chris Wright takes Kim Strassel through the findings, including the upsides of warming, the minimal economic effects of climate change, the limits of U.S. policy actions and the lack of evidence that climate is related to the frequency or intensity of extreme weather.

KS: Tell us why you commissioned that report.

CW: The climate chain is a real physical phenomenon. It’s scientifically fascinating. It is a truly global issue. But you know there’s certain facts and data about it. There’s certain implications about it. And most everything I hear in the media, in the news from politicians, from protesters when I speak at universities, they’re just so unaware of the basics of what is climate change.

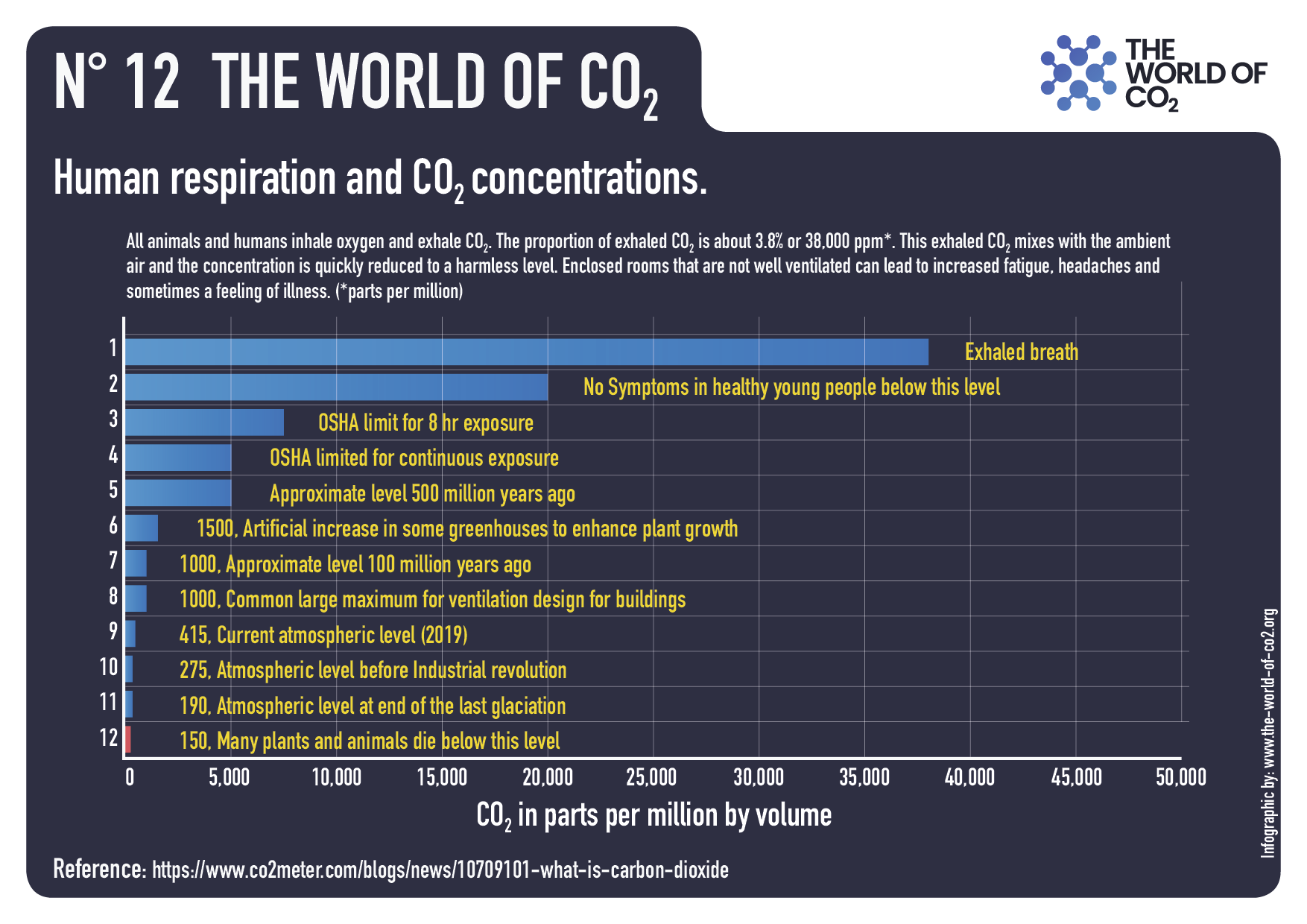

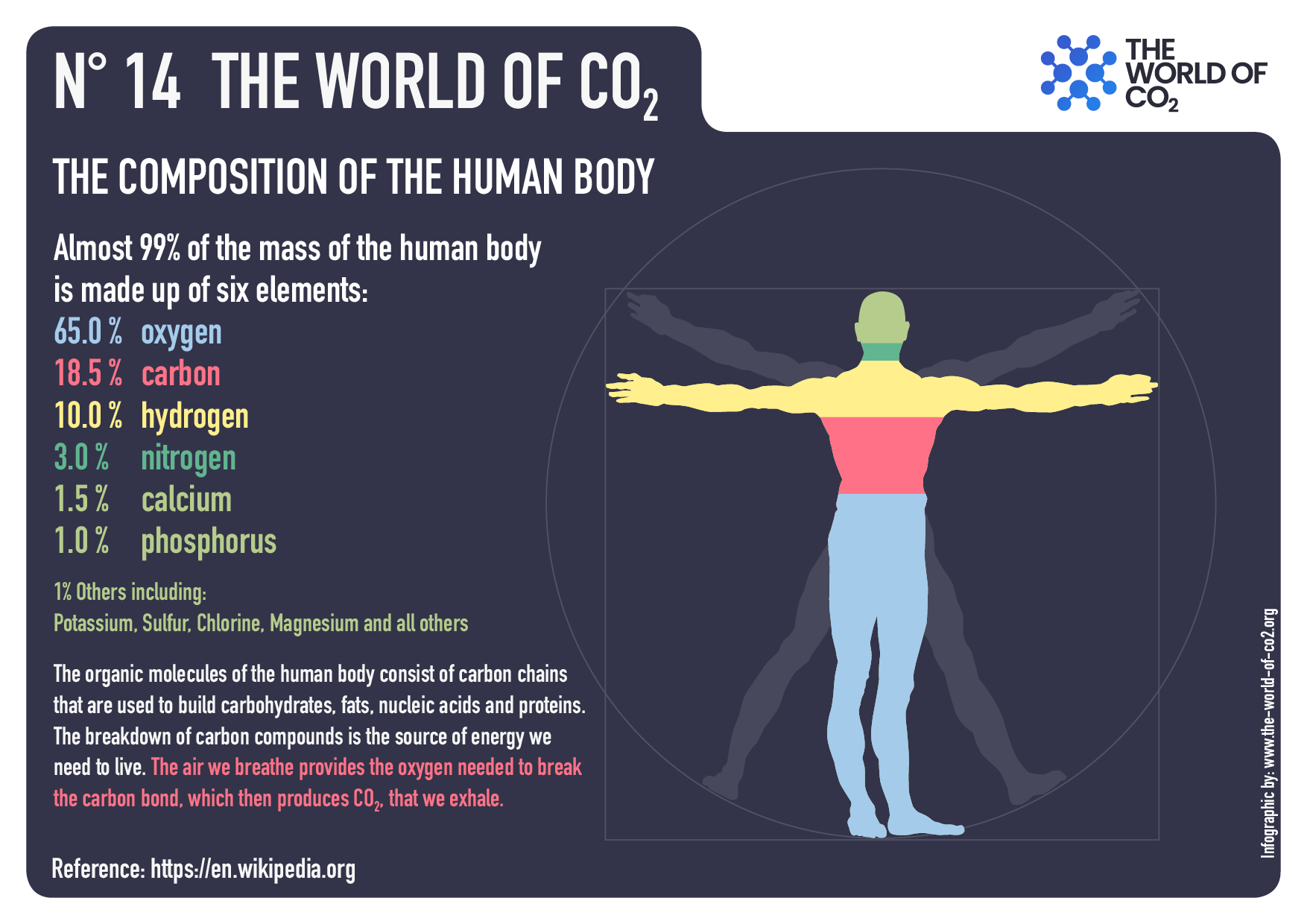

And and to give one example there, you hear these kids, I’m choking, I’m coughing on so much carbon pollution, you know. And look, the Clean Air Act was about real pollutants that do make you cough, that are toxic, that do have, you know, acute human impacts in local concentrations. As for carbon dioxide, I say it’s like oxygen and water, H2O, CO2 is one of the three most critical molecules for life on Earth. It is the essential life giving plant food that makes our life possible.

So it does absorb infrared radiation. So we can have a real dialogue about too much of it or too little of it. which is actually I think a bigger risk. But you know calling it a pollutant is just nuts.

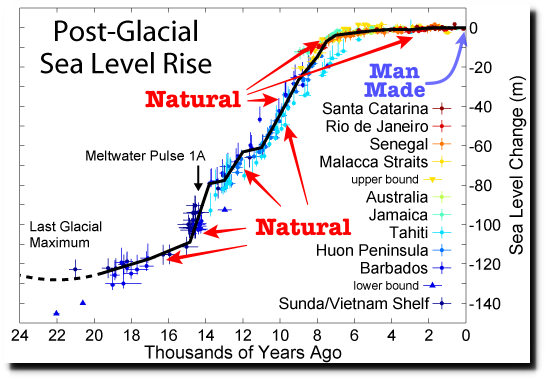

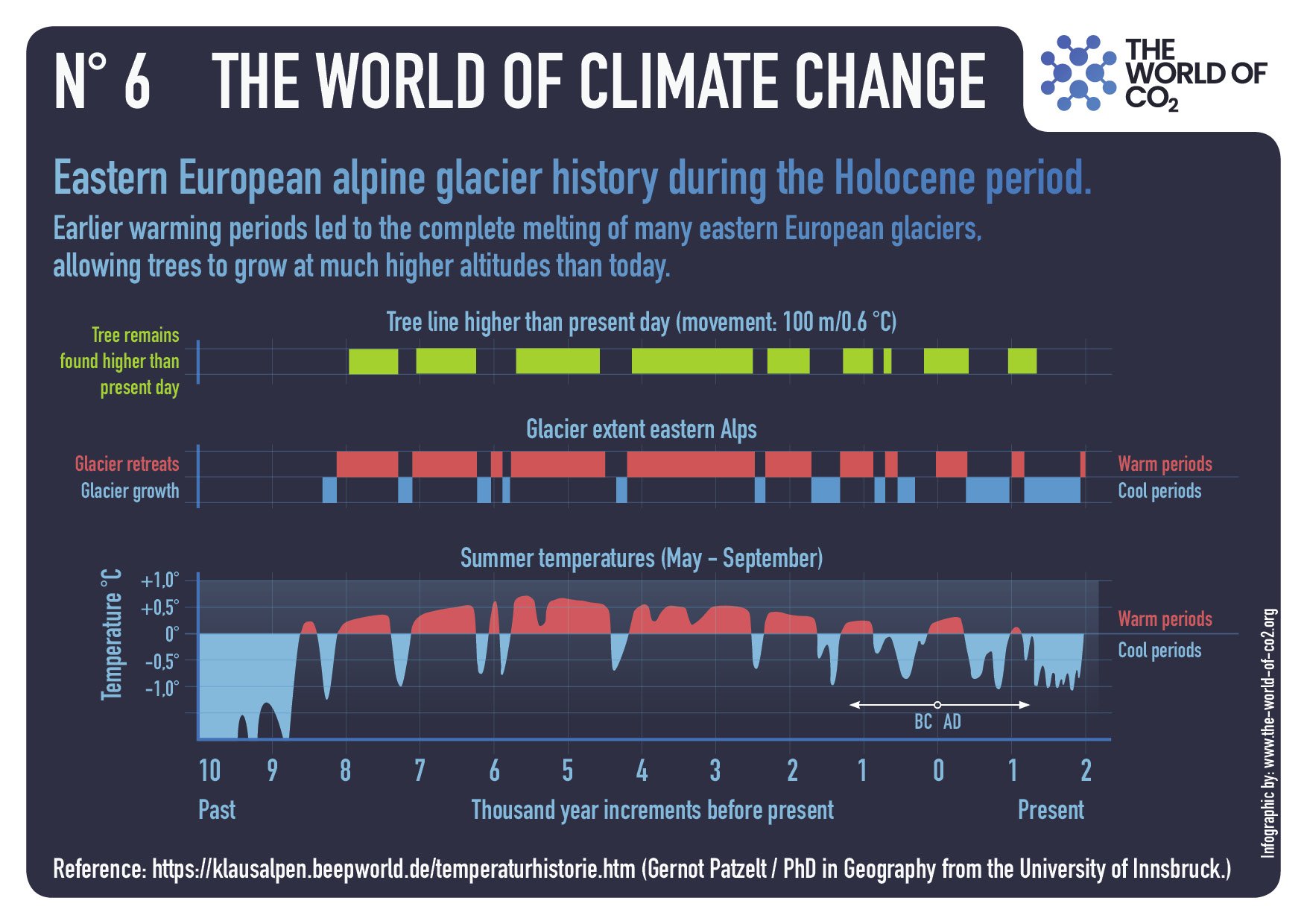

KS: So let’s go through some of the big takeaways of it because I think people would be amazed that it’s not what they hear in the media every day. One important thing that I think is is notable and I’ll just say it at the the top is that you know that no one in this entire report is denying that the climate is changing. We all agree that it’s changing. It’s always changing in some way.

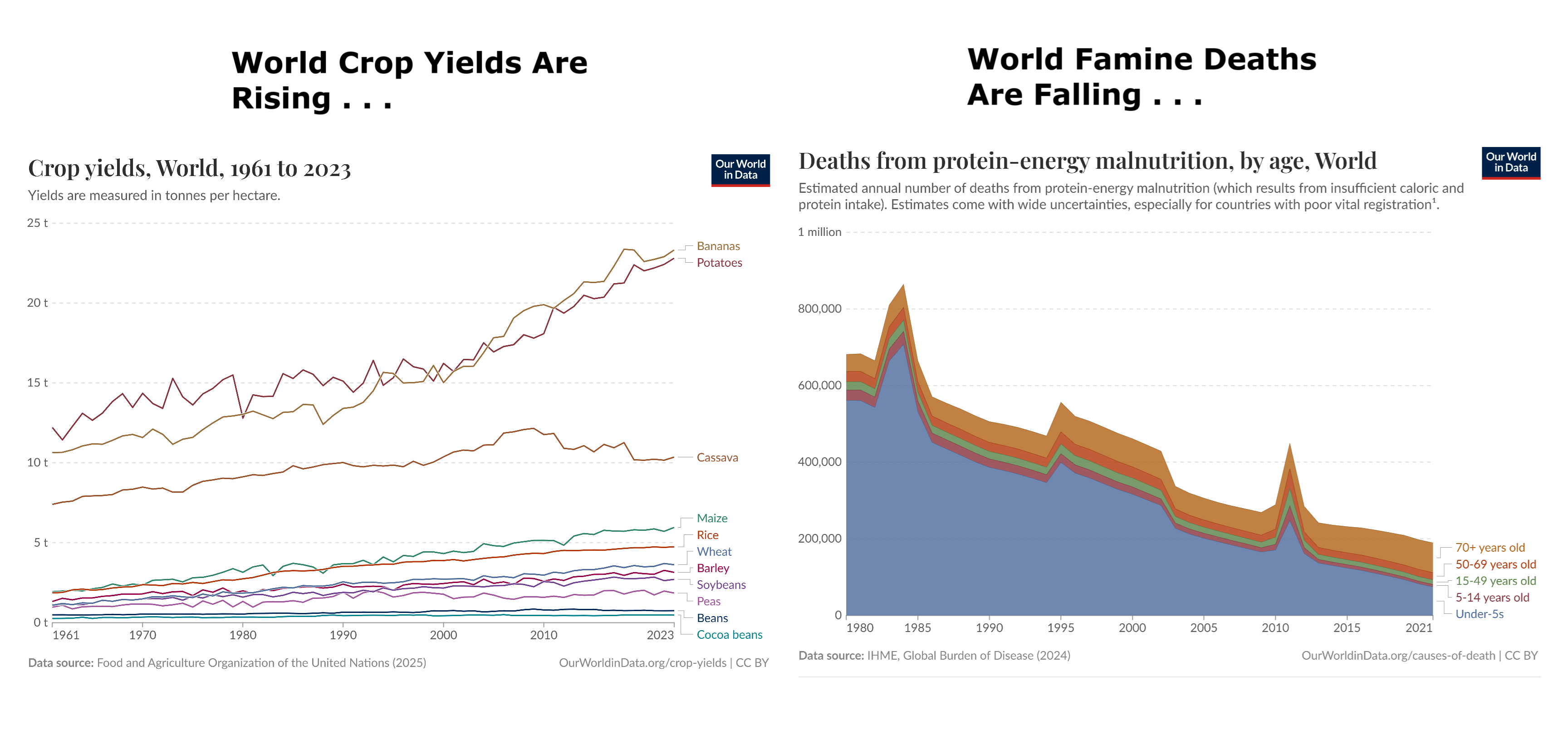

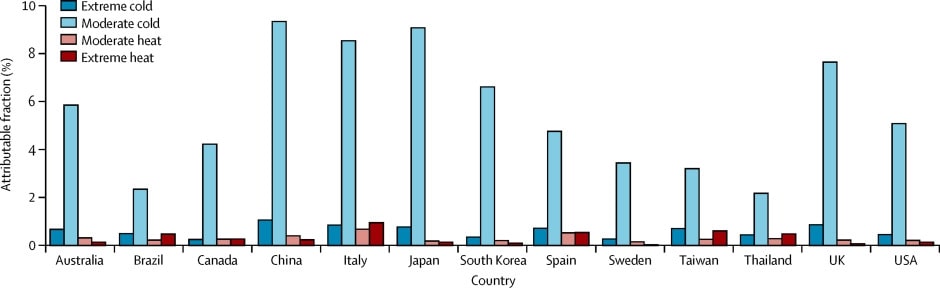

One thing that might surprise people was that some aspects of a changing climate can actually be good. Because you only ever hear about the apocalyptic points. But the report goes into some detail about how this can be better for agricultural production. It also talks about throughout history, cold has been a much greater threat to human health than heat. More people die from cold every year.

A 2015 study by 22 scientists from around the world found that cold kills over 17 times more people than heat. Thus the planet’s recent modest warming has been saving millions of lives.

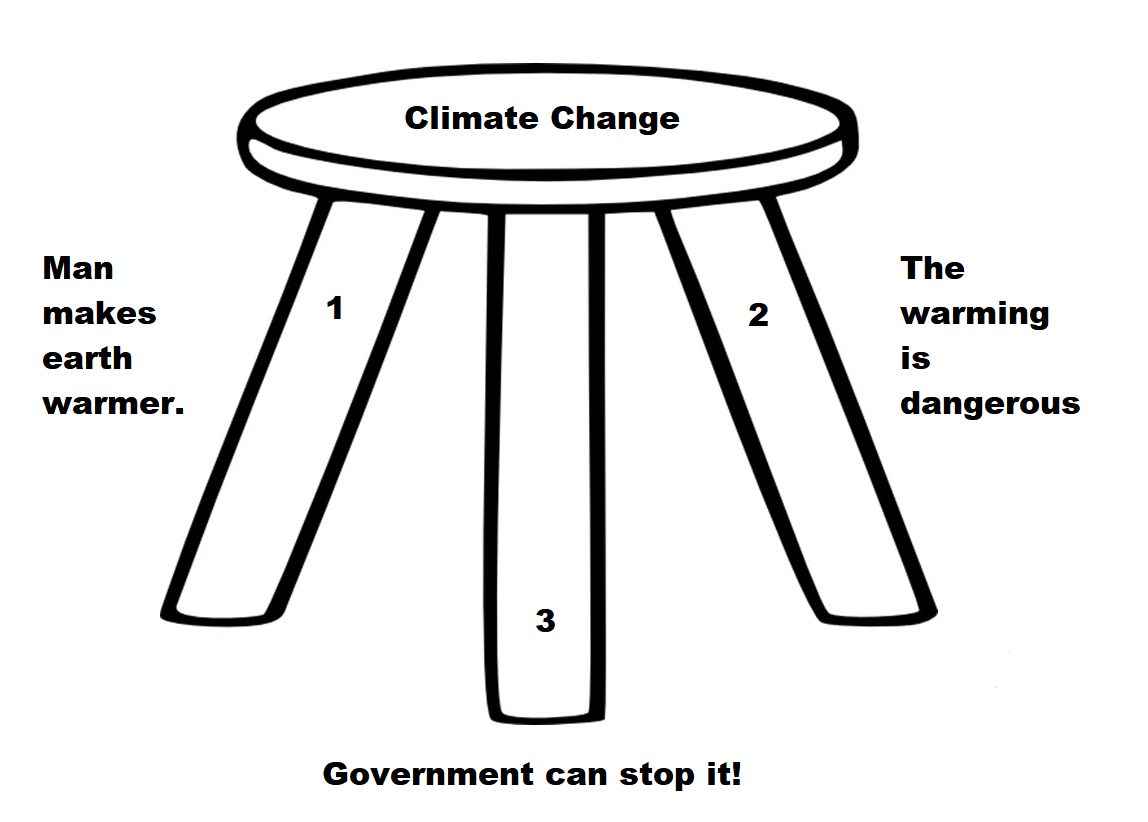

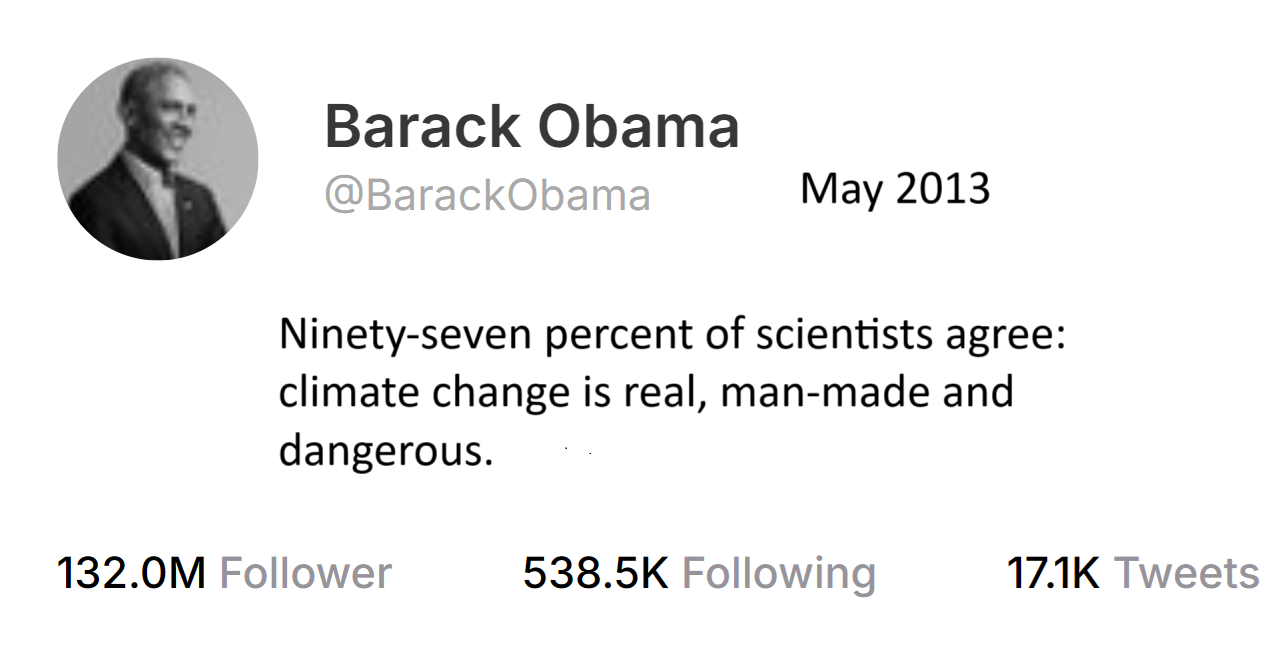

It might also surprise people that we still don’t know the extent to which humans really affect the climate. I would like you to talk about that because that’s going to be really confusing to some folks out there because all they hear is, the consensus is that humans are causing massive damaging climate problems. That’s what you constantly get from the media refrain on this. How do you put those through things? How do you explain that to folks who might be surprised with what this report says compared to what they have heard non-stop for more than a decade now?

CW: Of course everyone says that, Republican politicians, Democratic politicians, the media everywhere because that’s what they hear. But it shows they don’t actually read, and of course, why would people read these giant bureaucratic clunky reports from intergovernmental panel on climate change, the IPCC that you hear about? The problem with the IPCC is actually the layers of reporting. There’s the report that’s by the scientists, and then there’s the release or the summary for policy makers as they call it in the IPCC world that’s written by politicians and it is striking there are things in the summary for policy makers just directly contradictory to the science actually in the reports themselves.

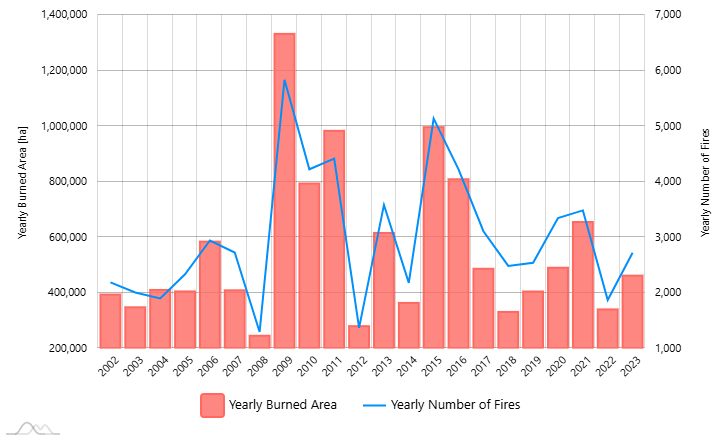

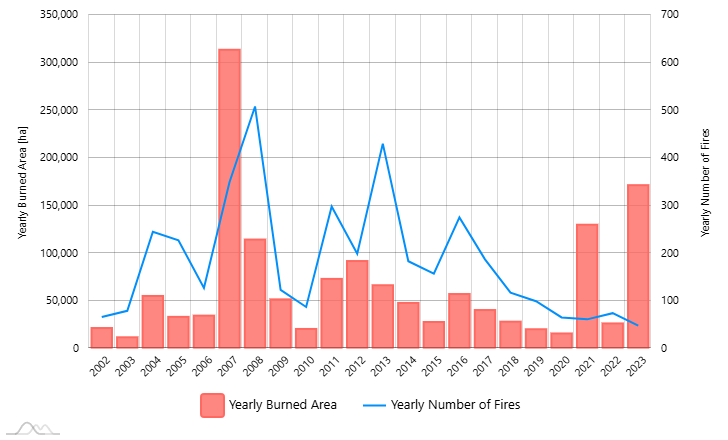

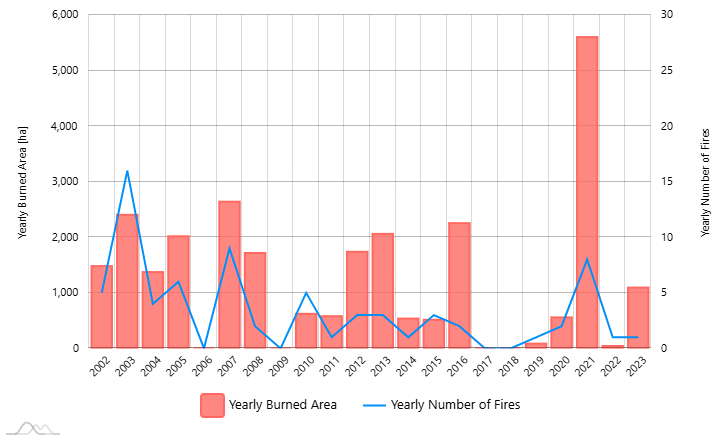

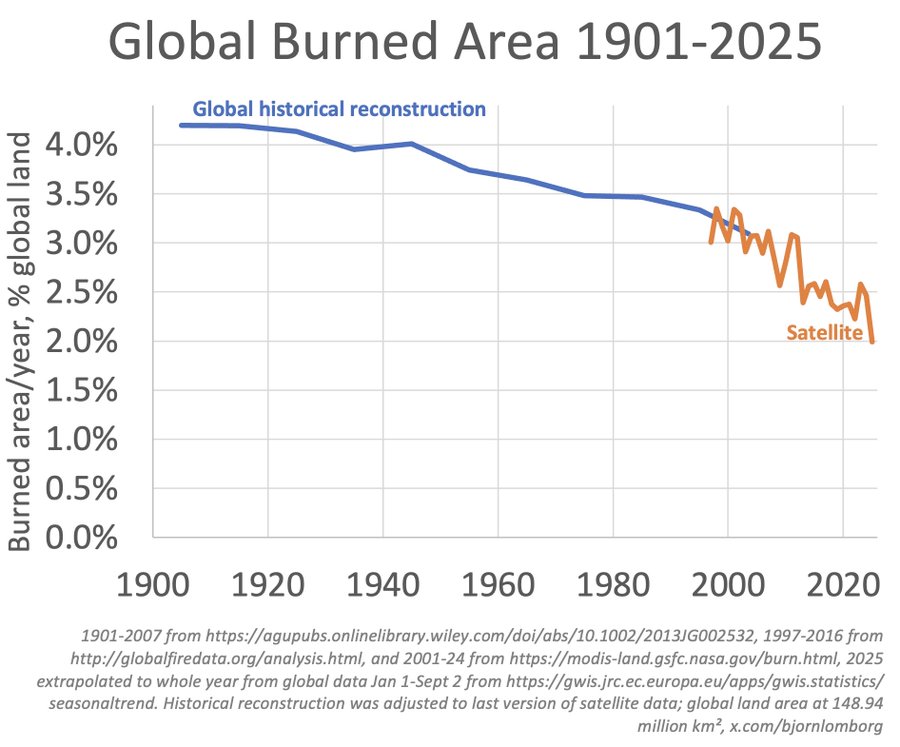

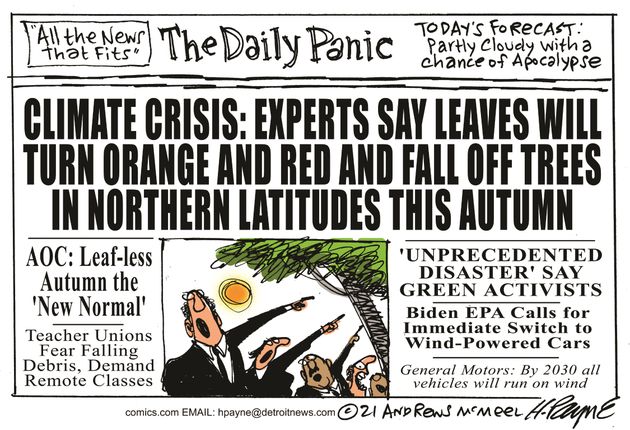

And the biggest thing there that everybody hears is that weather, extreme storms are getting stronger and more frequent and the damage of this is taking an increasing toll on society and hence we’re in a climate emergency. None of that is true and none of that is clear in the intergovernmental panel on climate change reports. These are the reports written by people that have dedicated their life to climate change.

If you thought ah you know it’s a real thing but it’s not that big of a deal, you’re not going to spend your whole life as an author of an IPCC report. It’s sort of self- selecting for the people most interested in climate change. They’re honest scientists, for the large majority of them, but they’re the most interested in this thing. Maybe they think it’s the most important thing, the most exciting to them.

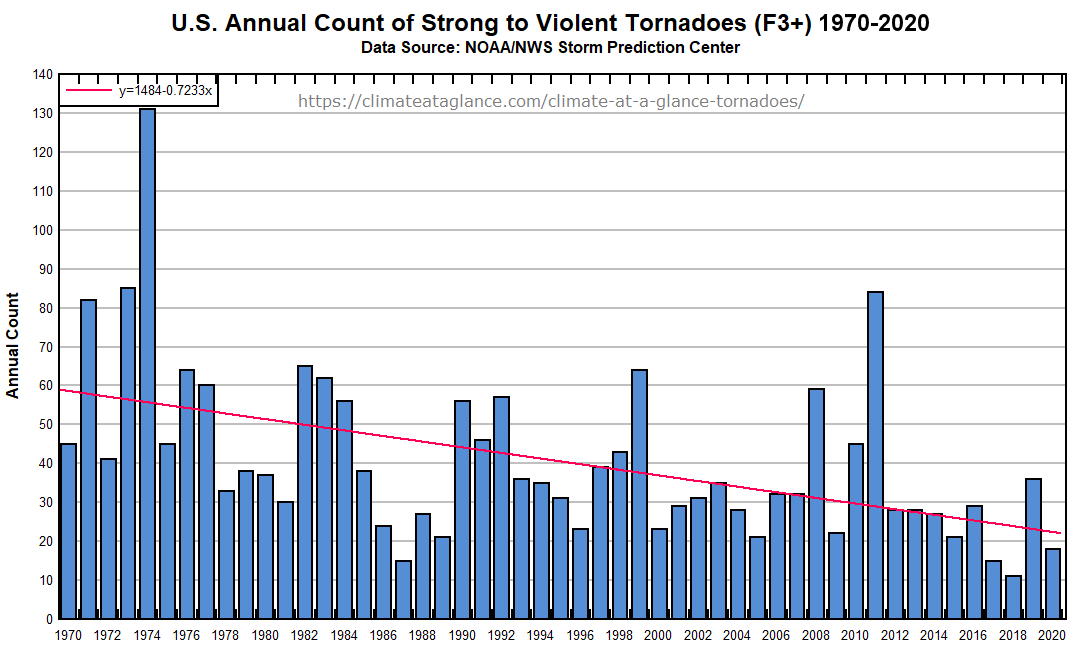

In these IPCC reports, there’s the collection of data on extreme weather: hurricanes, no increase in the frequency or intensity of hurricanes. floods, droughts, no increase in the frequency or intensity of them. The only the only meaningful extreme weather event that shows a trend and it’s not a huge trend is tornadoes and it’s downward. There’s like 50% less extreme high energy tornadoes today than 50 years ago. We don’t know why but you know that one’s sort of a favorable trend.

Most all of them have variations from year to year. Some of them have decadal oscillations. So they they go through phases of stronger and weaker but none of them show a scary upward trend. And my punch line, if you look at the deaths from extreme weather, they’ve just declined like a stone throughout the last hundred years, including in the last 20 or 30 years. So your risk of dying from extreme weather is the lowest we’ve ever had data on.

But yet 20% of kids report nightmares about fears of climate change. Like, how do those go together? And that’s despite the fact that we have much greater populations in a lot of these areas that are hit.

And that’s all useful information out there as well about not conflating the economic damage of a of a storm with meaning that it’s actually a bigger or worse storm. It just might mean that there were more things in its path to actually get wrecked. And people conflate those things too often with really sloppy consequences for the science.

KS: In the broader debate, if you look at many areas of science, for example we’ve been studying physics for millennia. There’s a been a lot of work done and a lot of people coming up with theories and then them getting knocked down. And we crawl our way forward but we have gained a pretty good understanding of many things in nature. Still climate science is new in the grand scheme of things, kind of in its infancy and we’re still learning a lot. Is that an accurate statement?

CW: Oh yeah. Look, it’s an incredibly complicated system. This is a tightly coupled, chaotic system. And you know, best exemplified by weather forecasts. We get better at weather forecasts now. 50 years ago, maybe you could have a reasonable projection out four or five days. Today, it’s closer to two weeks. There’s people in the AI world telling me we can do a reasonable projection all the way out to a month today. I’ve never seen that, but that is a claim of massive advanced computing going out a month. That’s just how complicated these phenomenon are.

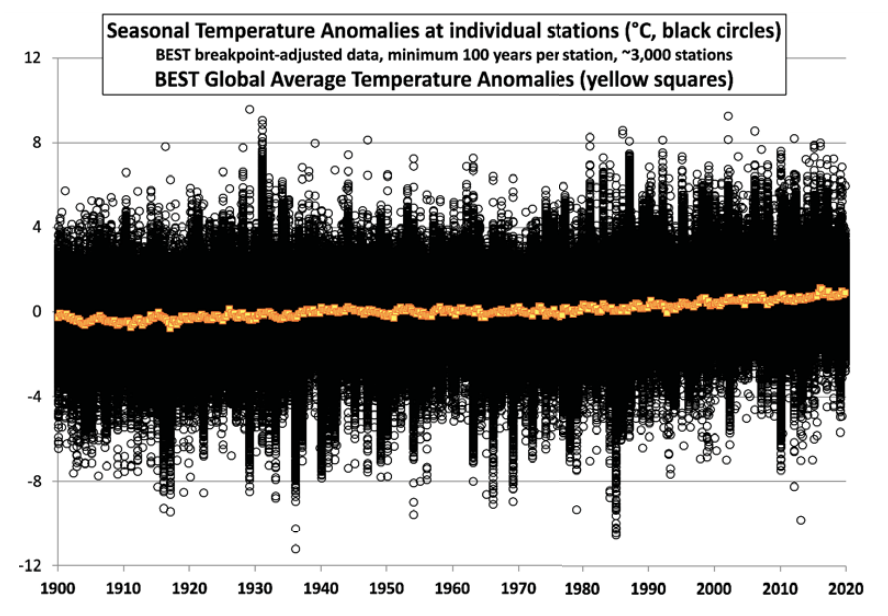

So when you come back and report that with this little knob CO2 concentration, you’re going to dial in to a tenth of a degree the temperature at the end of the century. That should be greeted with a lot of skepticism. There’s some reality. It is a warming fact. There’s a bias. There’s an upward average trend. But yeah, this you know attributing this storm, this much damage came from climate change.These are stretching science beyond science and going into science fiction.

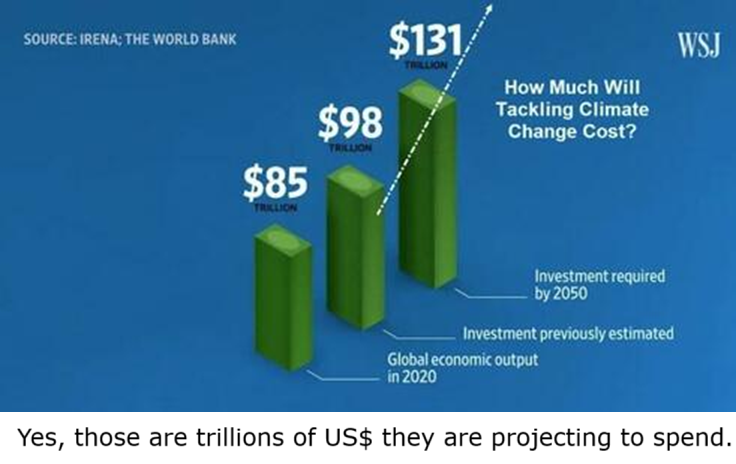

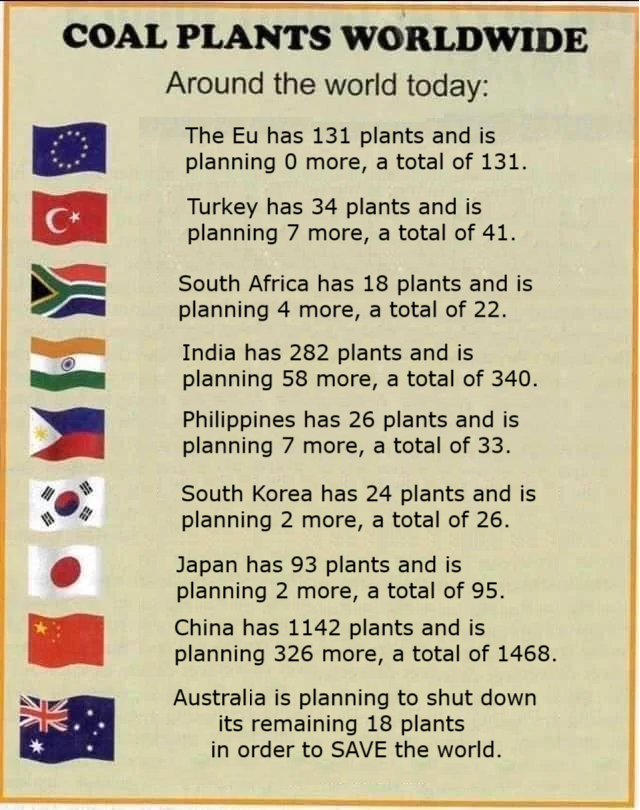

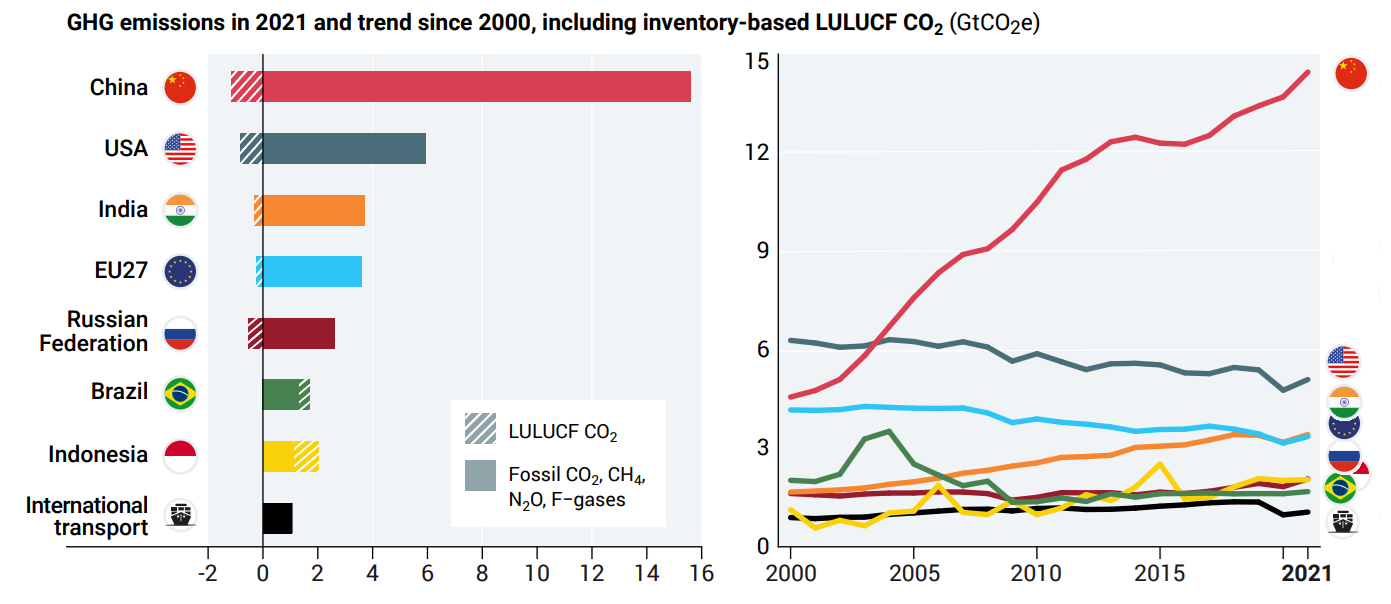

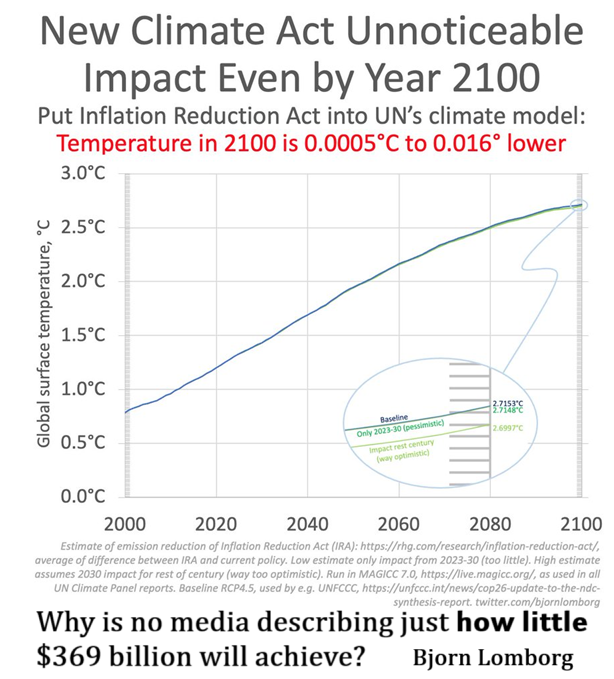

There are more items from this report that I think might surprise people. It is very important to broaden this out to a couple other findings that would surprise people One point is that there’s not been so far and they’re not projected to be a lot of negative economic effects from this. And moreover the US’s ability to change global climate is extremely limited. Even if we were to take some very drastic policy measures it would generally have a negligible effect on global climate trends.

And that’s another part of the IPCC reports that not only is never read, but it’s never even talked about. In the past, I put out the summary of what are the economic conclusions of the IPCC authors. They survey all the economic literature on climate change. And yet our current warming trends, the projections are that maybe at the end of this century, we might lose a few tenths of a percent or maybe two, three or four percent per capita income, if we do nothing about climate change by the end of this century.

But in that same model with economic growth projected ahead, we’re about 400% richer than we are today. So, our great great grandchildren might be 400% richer than us or in the worst case, if you take the outer bounds scenarios, well, they might only be 380 or 85% richer than us. I don’t think that qualifies as a climate catastrophe or this disaster meme around something projected to be relatively modest. And even in the words of the climate economists, they’ll say, “Look, climate impacts are nowhere near as important as education policy or trade impacts or efficiencies and other things.” So people studying these things closely, I think, are quite sober and reasonable about them.

The problem is you never hear from them. Only the most extreme ones that made the dramatic, you know, that, you know, the Statue of Liberty is going to be underwater, you know, the people that make the crazy claims, they’re the newsworthy ones. So they’re the ones that are put on TV all the time, but they’re not representative at all of the consensus.

Now consensus does not mean correct, but just the center point of people looking at this. Yeah. That you know their centrist view of climate change is a very slow moving but significant process. Nothing about alarmism, nothing about disaster. You know all the crazy stuff you hear is out of line with mainstream climate science and mainstream climate economics, but not the five authors of this report. They’re just making accessible to the broader public or at least the moderately scientifically inclined public to get in tune with what we think we know about climate change to date. They don’t talk a lot about projections because no one knows the future, but I think we’ve got a hundred years of pretty good data. That’s a good place to start when you’re trying to think how might things be in another 10 or 50 or 100 years.

KS: Yeah. And that’s what I loved about this report. If you go through it, every single statement in there is just common sense and you can’t really disagree with it if you’re looking at the numbers and the data. They really summed up the state of climate science at the moment.

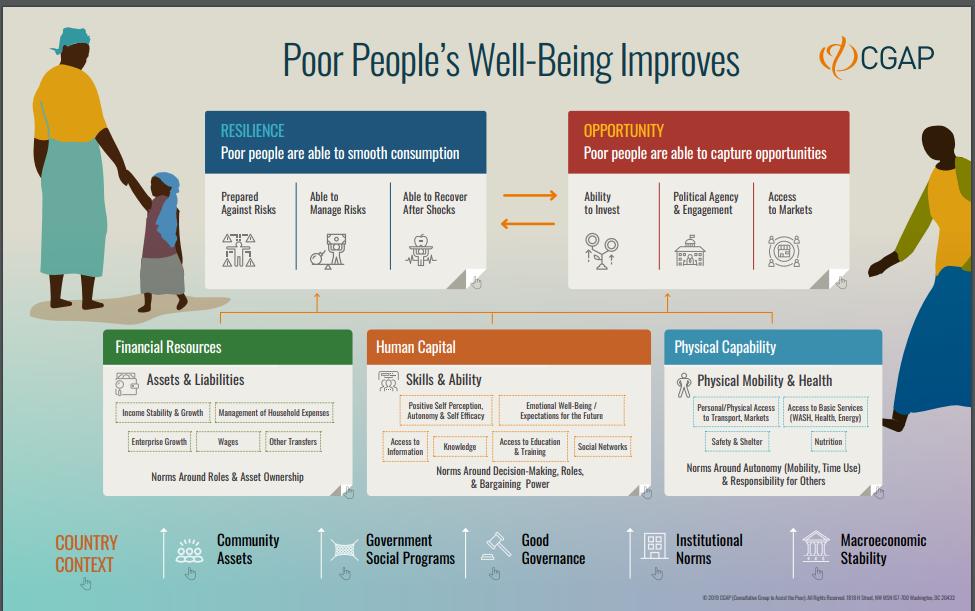

Why I like this report and the way you framed it in your introduction at the beginning is that we as a country and as a member of this globe, we’re always facing myriad problems. And if you don’t have the whole picture, it’s impossible to prioritize which of those to focus on because by the way, we do have limited focus and limited resources to sort of manage some of these to a certain degree. In your introduction you put that perhaps the world’s greatest problem at the moment is actually energy poverty. And to fix that, to truly lift people up, we need reliable, affordable energy.

CW: And that’s just common sense. And in fact, I would say that’s why President Trump got elected. People were eventually tiring of these kind of alarmist claims that didn’t seem to make much sense. You know, every every 10 years the world’s going to end 10 years from now. And and honestly, unless you’re watching the news, no one would notice climate change if it was not in the news. If I were to change the temperature in the room you’re sitting right now by a couple degrees Fahrenheit over 20 minutes, you wouldn’t even notice it unless you’re very sensitive. I’m not. But that two degrees Fahrenheit, that’s the warming the planet has observed over a century, you know. But if I did it in 10 minutes or 15 minutes, you wouldn’t notice it.

So, President Trump got elected because, you know, 15%, 20% of Americans are struggling to pay their monthly electricity bill. They’re struggling to pay for gasoline to get to work. They’re struggling to start a new business because energy costs and energy connections are more expensive. That’s a problem in the here and now.

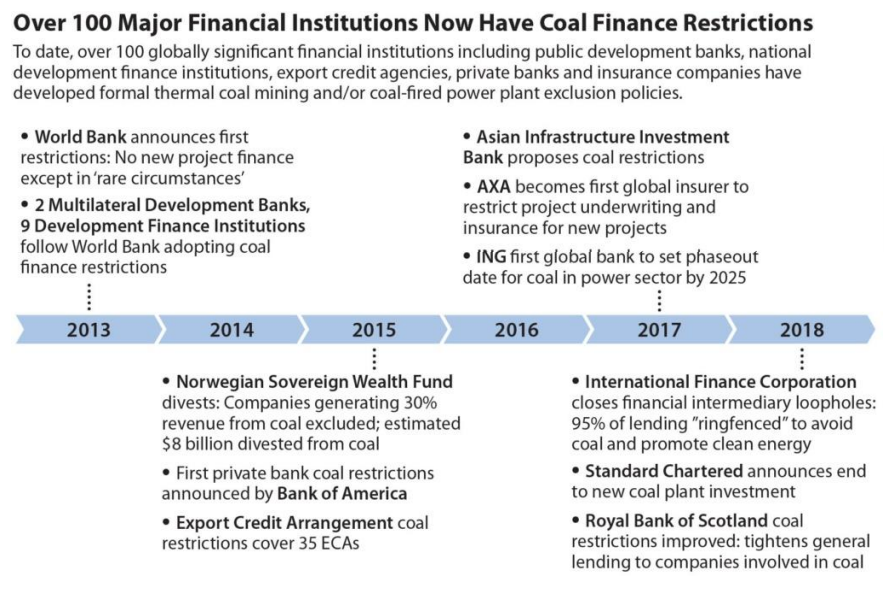

And that’s not an unrelated problem. We’ve driven up the cost of energy in the United States and Europe has done it dramatically all in the name of combating climate change. You know, we’re barely tweaking global emissions of greenhouse gases that might lead the planet to be a hundredth of a degree cooler in the year 2100. That’s the potential output if we implement these policies, but yet the short-term impacts are just crushing people’s opportunities and the ability to pay their bills. That’s getting way way off track.

That’s why the American public elected President Trump and maybe why President Trump tapped me. What I want to do is engage the public in this discussion: what do we know about climate change? What do we know about energy systems and how they could change and what kind of trade offs do we want to make? And the more people get exposed to the facts, the more I think people become realistic.

You talked about affordability problems in the United States. Let me just give one other punchline, World Health Organization data. Around two to three million people die every year from indoor air pollution. And that’s because two billion people, a quarter of humanity, cook their daily meals and heat their homes burning wood or dung or agricultural waste indoors. That smoke is just a deadly toxic pollutant that kills millions and crushes the freedom of women and children who gather the wood and spend hours a day over these smoky fires.

That’s an energy crisis we know how to solve. It’s affordable. It’s reliable and massively transformative of lives. But yet we never hear about that. That’s clearly a bigger priority than shaving a few hundreds of a degree off global temperatures three or four generations from now.

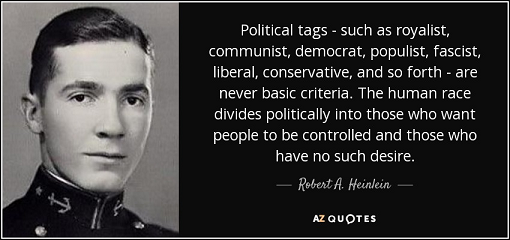

KS: Last question here, I do just want to ask a political question. Those of us who believe in free markets, who want opportunity, abundance, you know, the ability for people to succeed and have more, have understood a long time ago that if the activist climate agenda were imposed from above and government, that’s just an end to most of those free market ambitions. Because in order to to follow the agenda they want, which is total control over what you drive and what you eat and what kind of job you have and what kind of house you live in. You squash that freedom.

And I think a lot of free marketers have nonetheless struggled to know how to engage in these climate wars. For a while they said, “Well, the climate’s not changing.” And then for a while it was like, “It’ll just cost too much.” And then for a while it was, “Well, we’ll just have to do everything all of the above.” You seem to be saying, actually, you want to talk about the science, let’s talk about the science. And what it actually shows is that we don’t need to go down that road of of stripping everything away to control everything given the actual level of what we’re dealing with here. Is that right?

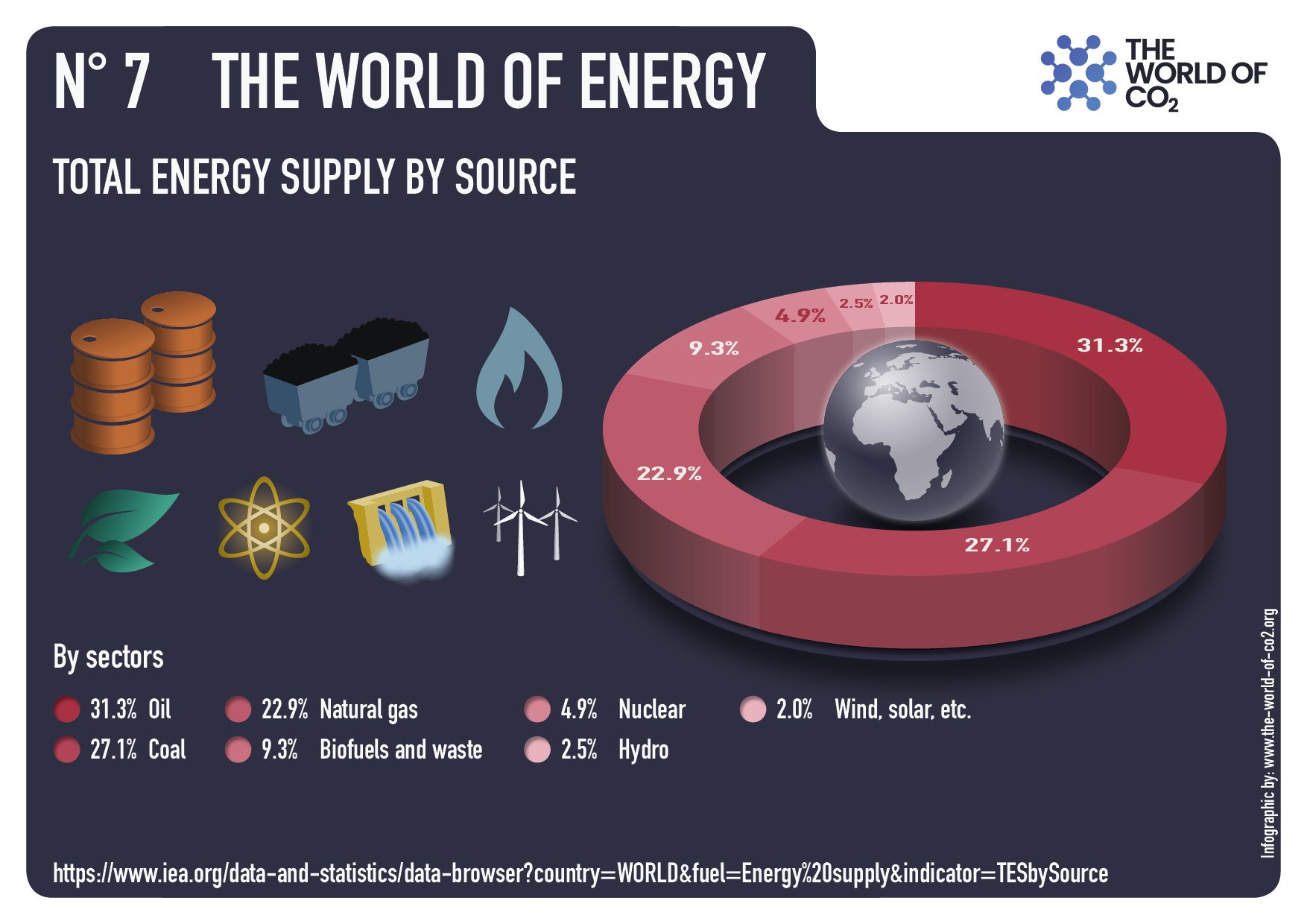

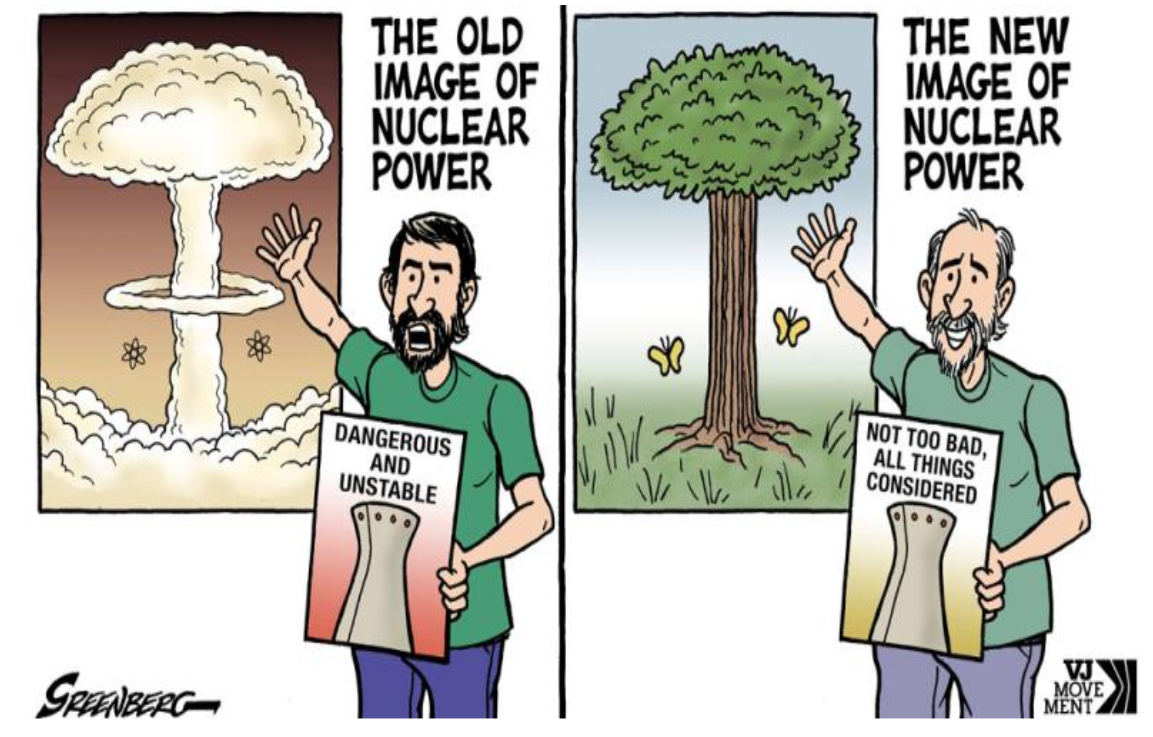

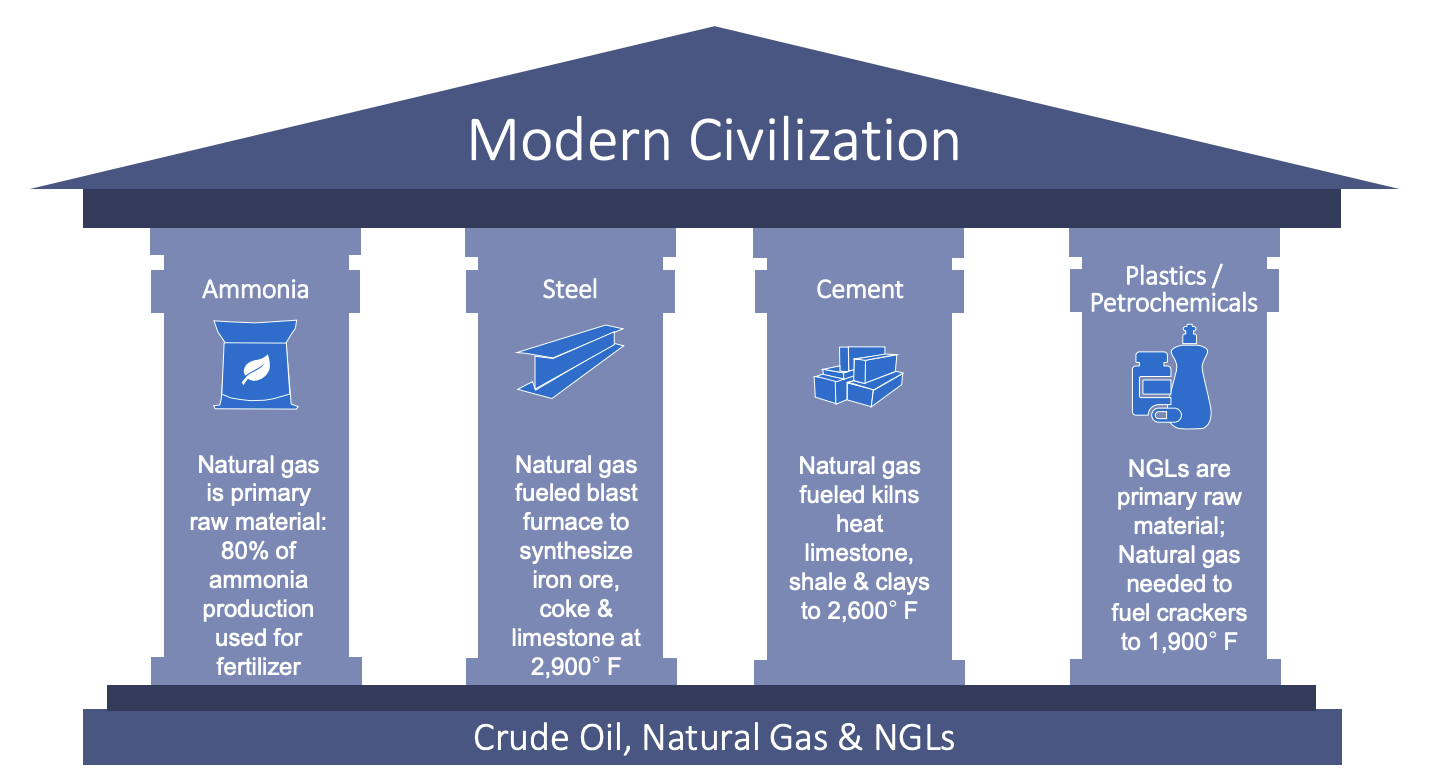

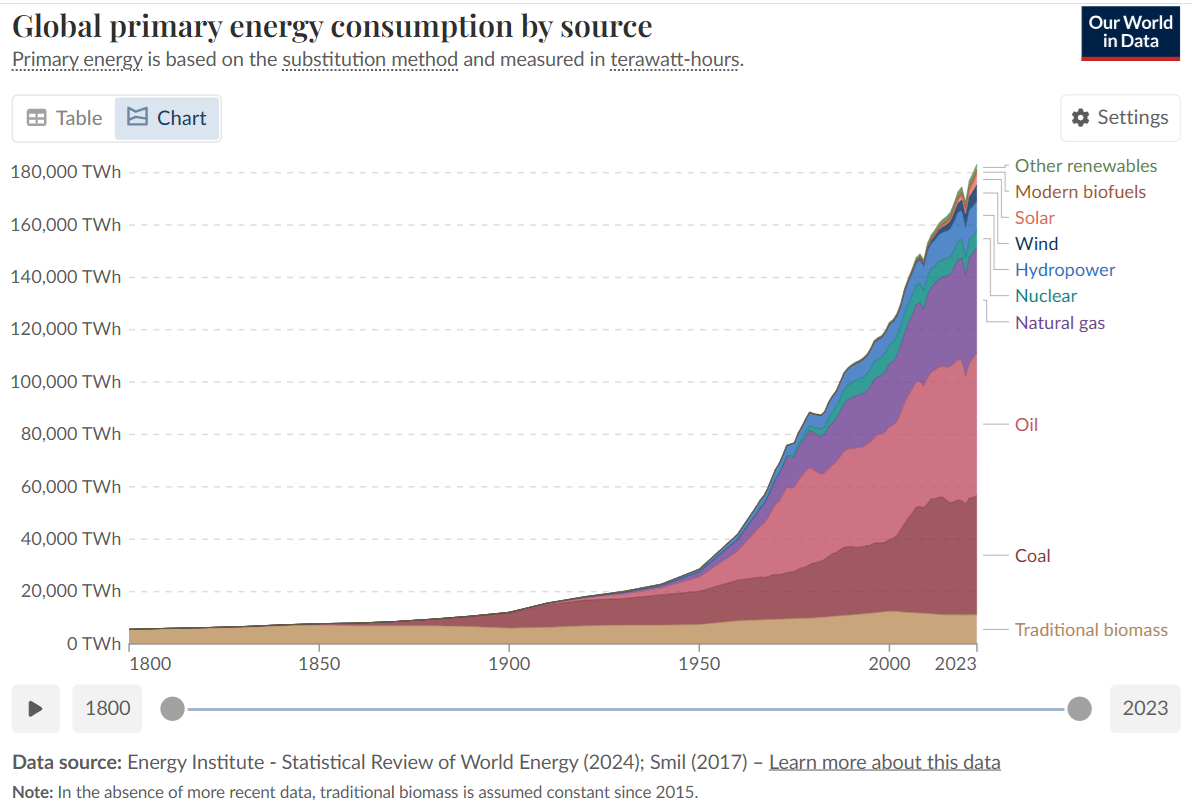

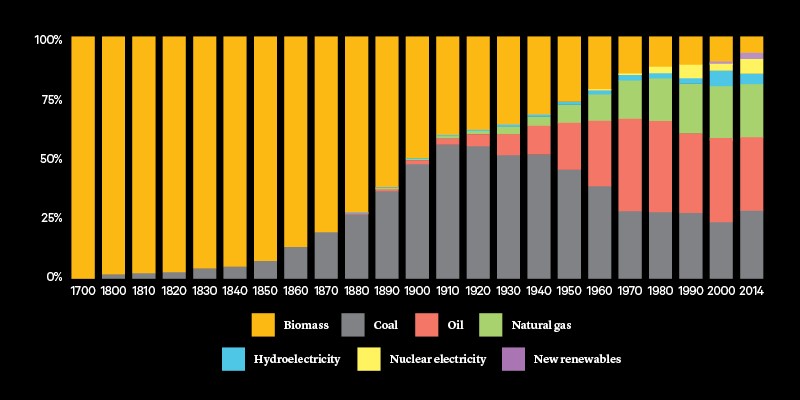

CW: That’s right, Kim. Yeah. And I say two things created the modern world. doubled our life expectancy, you know, created planes, trains, and automobiles and modern medicine. The growth of human freedom, bottom-up social organization or human liberty, and the explosion in affordable energy from the arrival of hydrocarbons. First coal, then oil, then wood, and now the derivative energy sources of hydrocarbons like nuclear, hydro, wind, and solar. You can’t have any of those without abundant hydrocarbons.

And this climate movement opposes both of them. They’re making energy more expensive. They’re trying to get in the way of the main energy source. Hydrocarbons were 85% of global energy when I was born and they’re 85% of global energy today. Turns out it’s hard to change the energy system, but they’re making them more expensive.

And to your point, they’re going back to top-down control. The government’s going to decide what’s virtuous, what car you can buy, how you can heat your home. We’re going to force you to electrically heat your home, which is two to five times more expensive than burning natural gas. And when you heat your home electrically, guess what? The US’s main source of electricity comes from natural gas.

You’re not even changing. You’re not reducing gas consumption. You’re just making it more expensive. But it’s about political control. It’s about reducing human freedom. So, let’s do this. Let’s shine light on all of this on the trade-offs we’re making. And I think Americans will choose a much more reasonable, informed pathway for energy and climate policy going forward.

I’m hugely optimistic. Shining light on this, I think, is going to get us to a much better place.