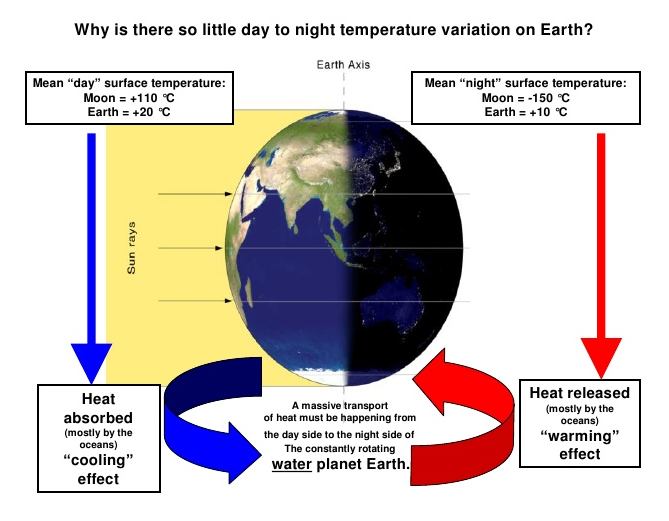

A continuing theme of this blog is Oceans Make Climate, coined by Dr. Arnd Bernaerts. He further explained: ” Climate is the continuation of ocean by other means.” The focus of this post is the North Atlantic which directly impacts weather and climate experienced by the populated continents of Europe and North America.

A continuing theme of this blog is Oceans Make Climate, coined by Dr. Arnd Bernaerts. He further explained: ” Climate is the continuation of ocean by other means.” The focus of this post is the North Atlantic which directly impacts weather and climate experienced by the populated continents of Europe and North America.

North Atlantic is a Climate Driver

The importance of this basin is described by Börgel et al. (2020) The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation controls the impact of the North Atlantic Oscillation on North European climate. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Abstract

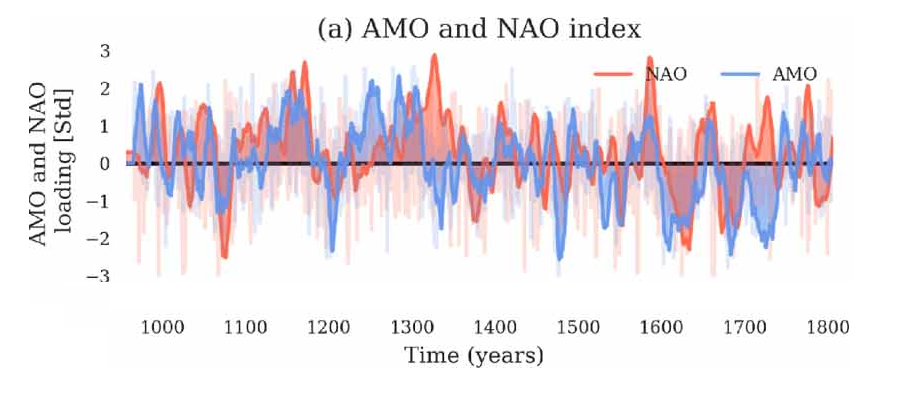

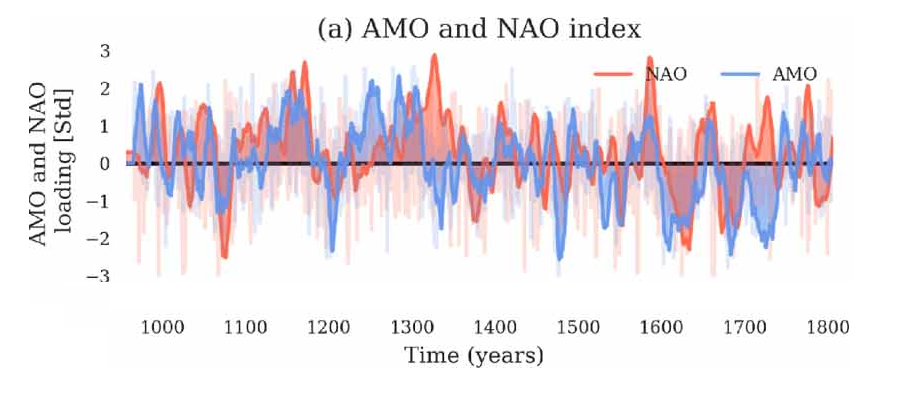

European climate is heavily influenced by the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). However, the spatial structure of the NAO is varying with time, affecting its regional importance. By analyzing an 850-year global climate model simulation of the last millennium it is shown that the variations in the spatial structure of the NAO can be linked to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). The AMO changes the zonal position of the NAO centers of action, moving them closer to Europe or North America. During AMO+ states, the Icelandic Low moves further towards North America while the Azores High moves further towards Europe and vice versa for AMO- states. The results of a regional downscaling for the East Atlantic/European domain show that AMO-induced changes in the spatial structure of the NAO reduce or enhance its influence on regional climate variables of the Baltic Sea such as sea surface temperature, ice extent, or river runoff.

Natural Factors Operating in N. Atlantic

The main mechanisms operating in this basin are defined as follows:

AMO (Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation) refers to the phase changes of N. Atlantic SSTs (Sea Surface Temperatures). There is also the AMOC (Atlantic Multidecadal Overturning Oscillation) referring to the oceanic “conveyer belt” transporting water between the warm tropics and the cold poles. The NAO (North Atlantic Oscillation) is the air pressure dipole alternating highs and lows between the Azores and Iceland.

The current state of scientific understanding is indicated by a recent paper Seip and Wang (2022) The North Atlantic Oscillations: Lead–Lag Relations for the NAO, the AMO, and the AMOC—A High-Resolution Lead–lag Analysis. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Abstract

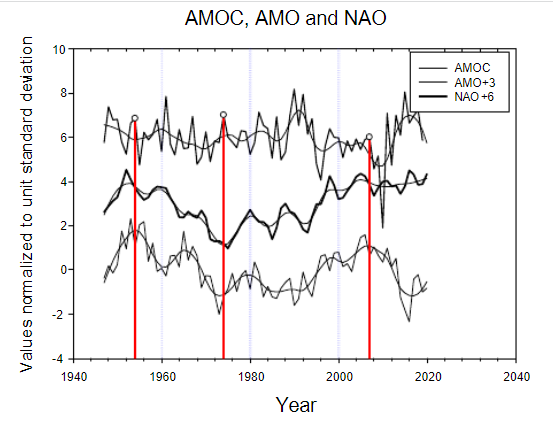

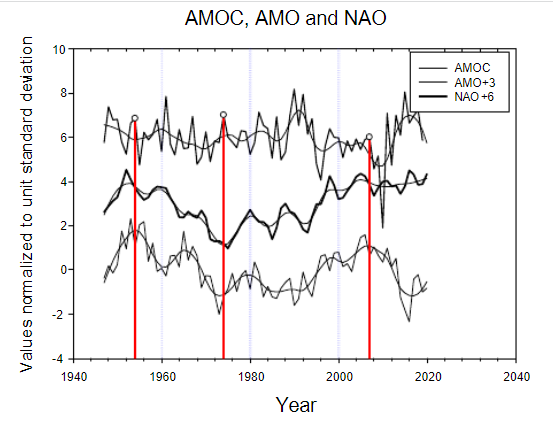

Several studies examine cycle periods and the interactions between the three major climate modes over the North Atlantic, namely the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (AMO), and the North Atlantic oscillation (NAO). Here, we use a relatively novel high-resolution lead–lag (LL) method to identify short time windows with persistent LL relations in the three series during the period from 1947 to 2020. We find that there are roughly 20-year time windows where LL relations change direction at both interannual, high-frequency and multidecadal, low-frequency timescales. However, with varying LL strength, the AMO leads AMOC for the full period at the interannual timescale. During the period from 1980 to 2000, we had the sequence NAO→AMO→AMOC→NAO at the interannual timescale. For the full period in the decadal time scale, we obtain NAO→AMO→AMOC. The Ekman variability closely follows the NAO variability. Both single time series and the LL relation between pairs of series show pseudo-oscillating patterns with cycle periods of about 20 years. We list possible mechanisms that contribute to the cyclic behavior, but no conclusive evidence has yet been found.

Figure 2.AMOC, AMO and NAO. (a) Time series raw and LOESS(0.3)-smoothed. The detrendedand LOESS(0.3)-smoothed versions of AMOC shifts sign from starting with (+) in 1947, then 1969,1997, 2010. AMO starting from (+) in 1947, 1996, 1999. NAO starting from (+) in 1947, 1952, 1972,1997, 2014, 2020.

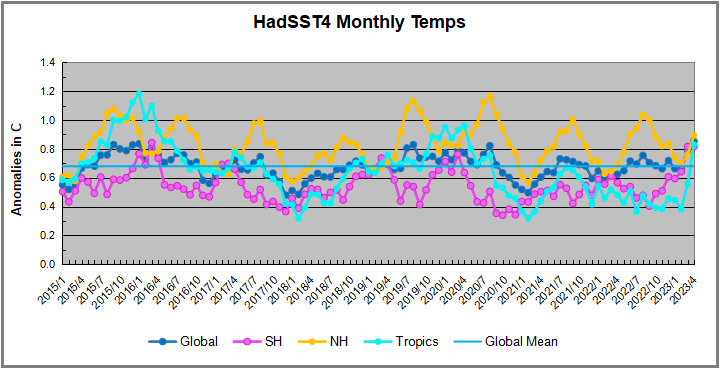

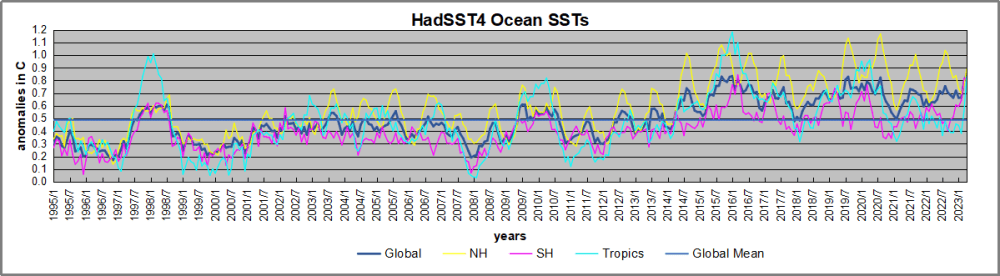

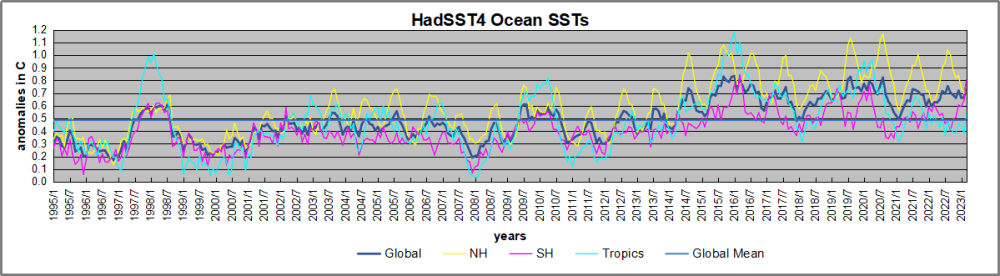

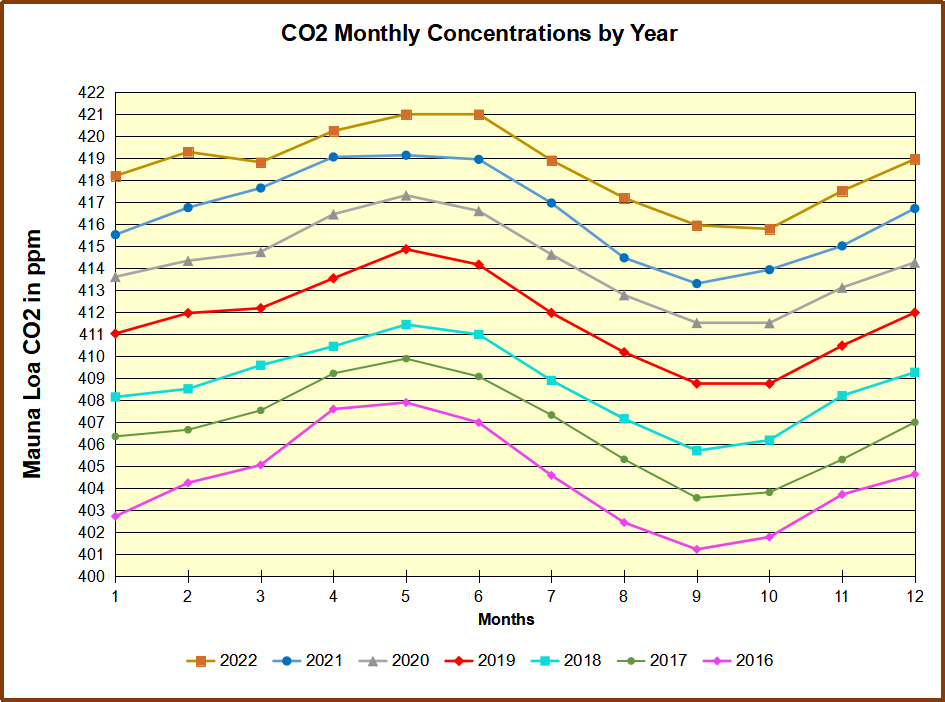

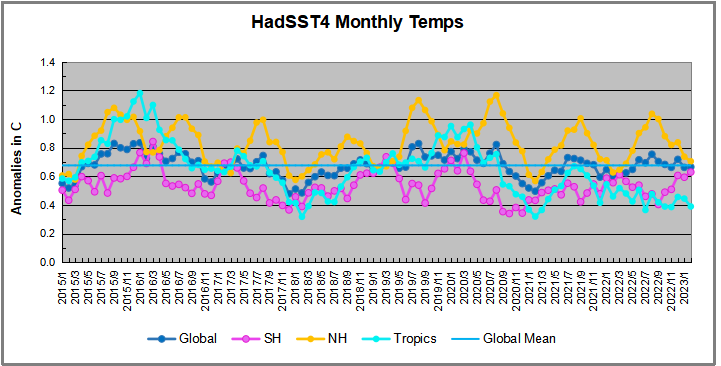

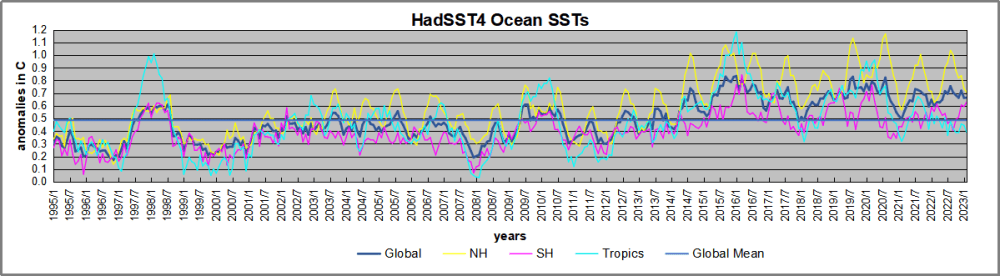

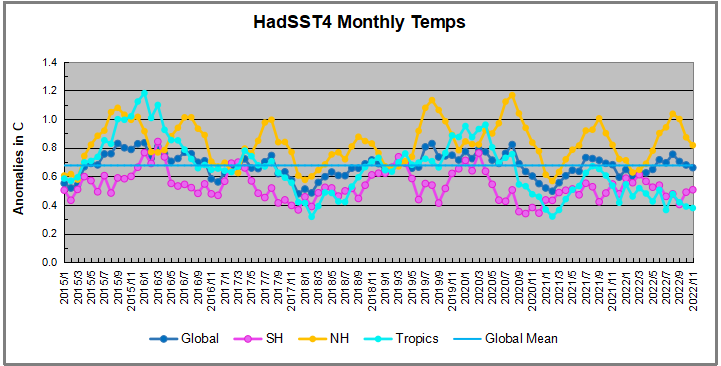

Contemporary AMO Observations

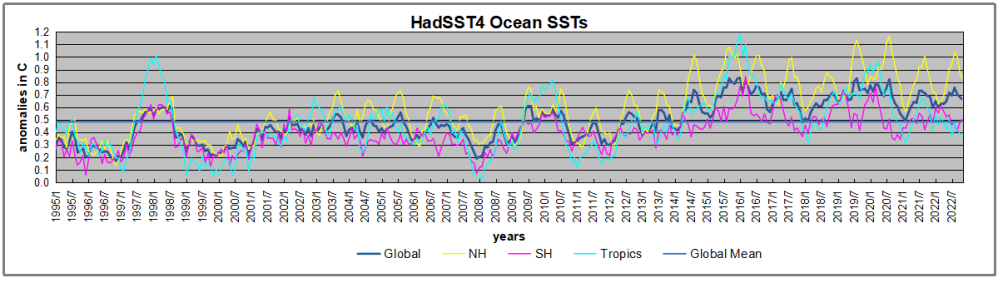

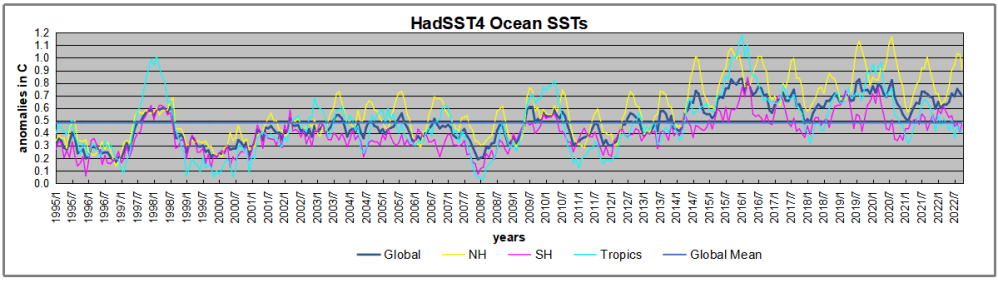

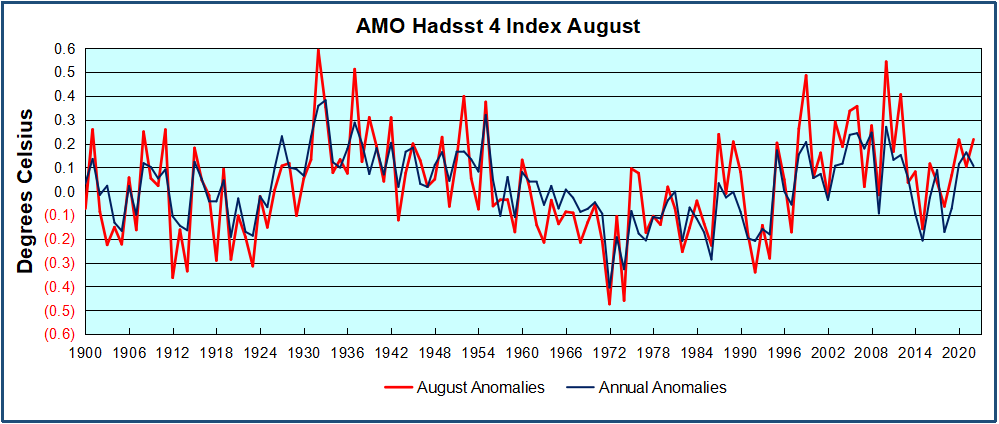

Through January 2023 I depended on the Kaplan AMO Index (not smoothed, not detrended) for N. Atlantic observations. But it is no longer being updated, and NOAA says they don’t know its future. So I find only the Hadsst AMO dataset has Feb. and March data. It differs from Kaplan, which reported average absolute temps measured in N. Atlantic. “Hadsst AMO follows Trenberth and Shea (2006) proposal to use the NA region EQ-60°N, 0°-80°W and subtract the global rise of SST 60°S-60°N to obtain a measure of the internal variability, arguing that the effect of external forcing on the North Atlantic should be similar to the effect on the other oceans.” So the values represent differences between the N. Atlantic and the Global ocean.

The AMO index as defined as the SST averaged over 0°-60°N, 0°-80°W minus SST averaged over 60°S-60°N.

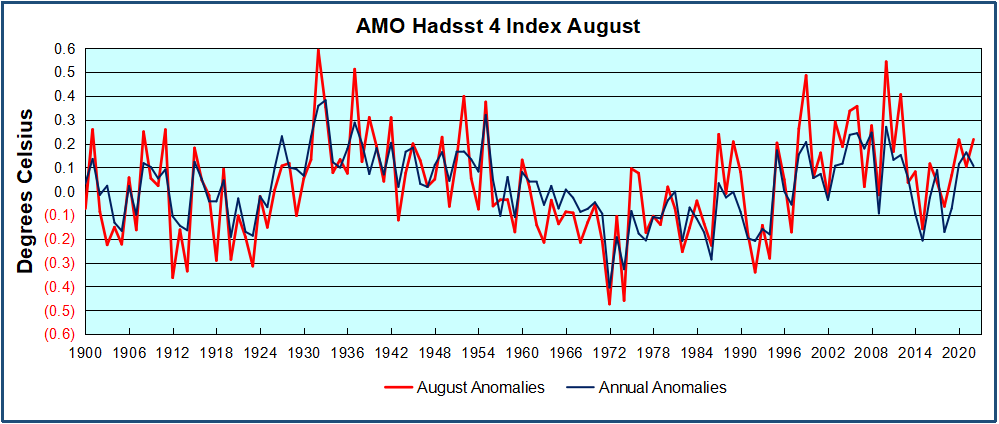

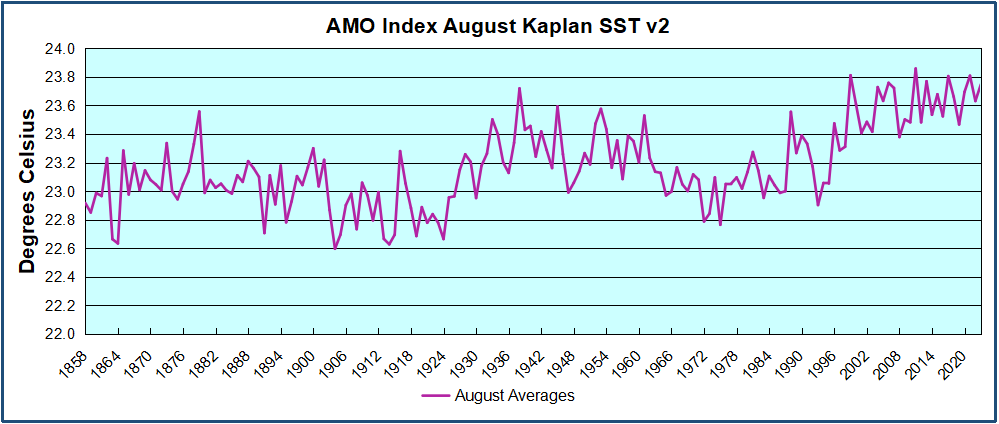

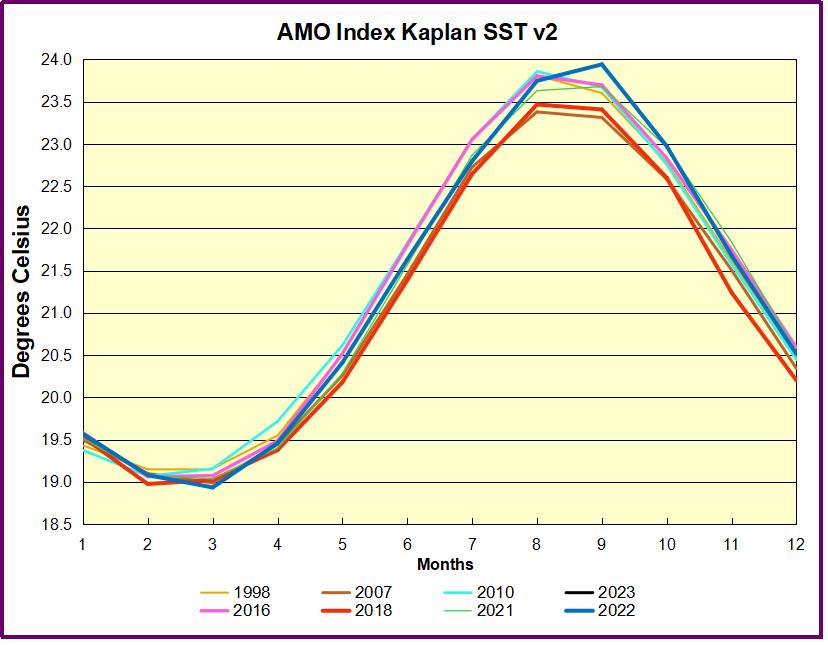

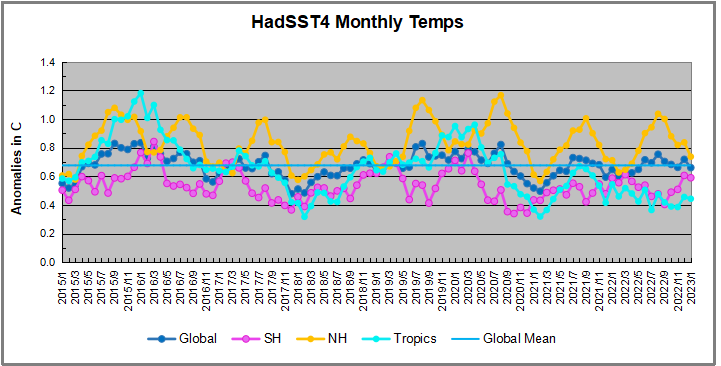

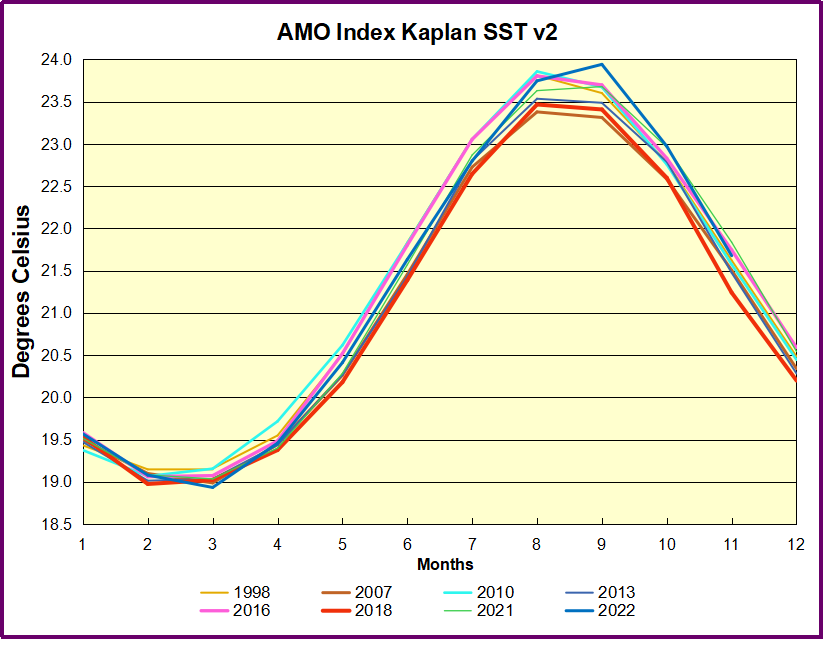

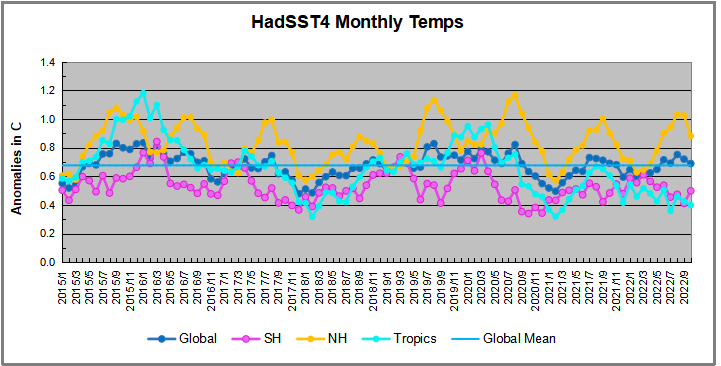

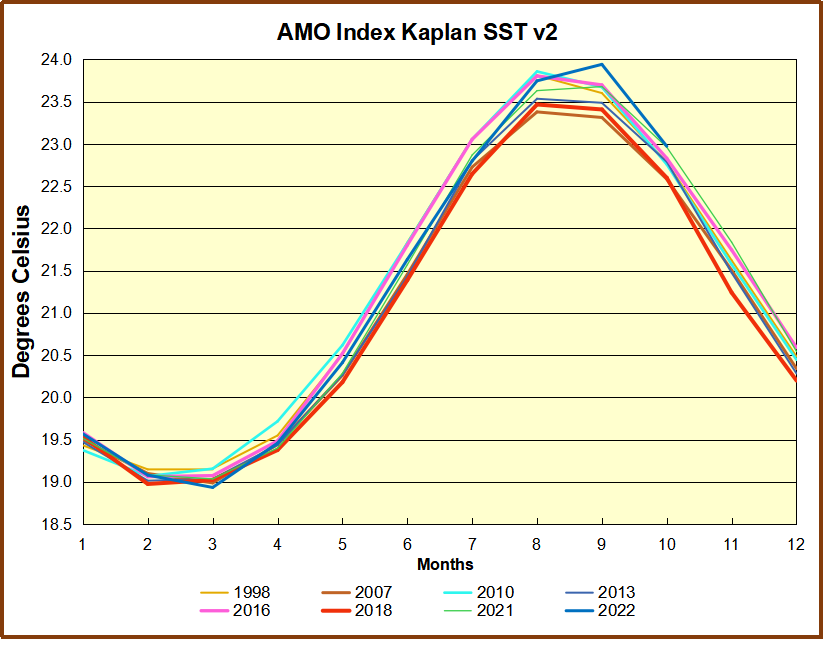

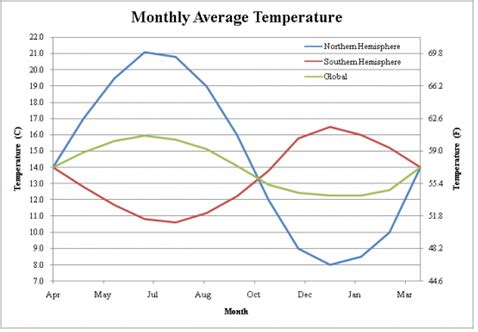

The chart above confirms what Kaplan also showed. As August is the hottest month for the N. Atlantic, its varibility, high and low, drives the annual results for this basin. Note also the peaks in 2010, lows after 2014, and a rise in 2021. An annual chart below is informative:

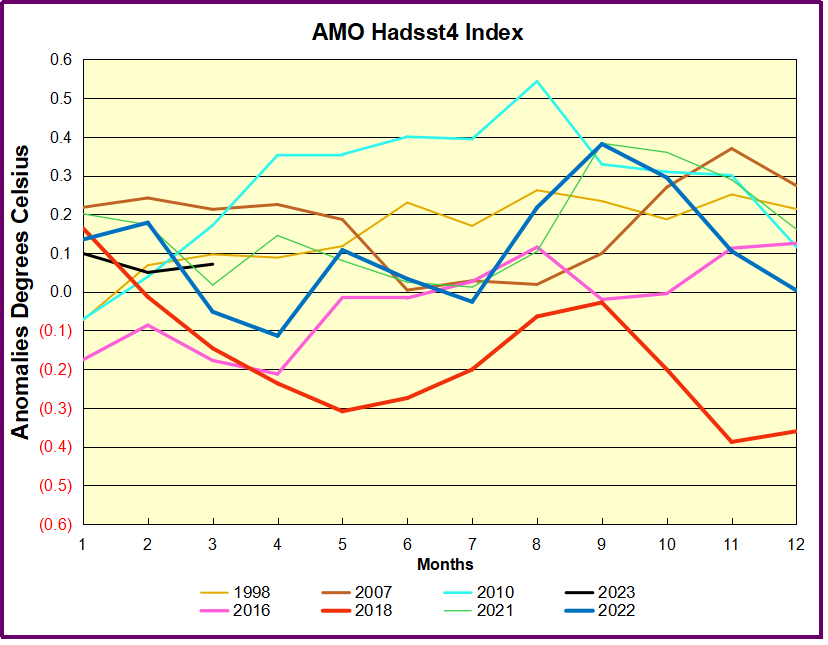

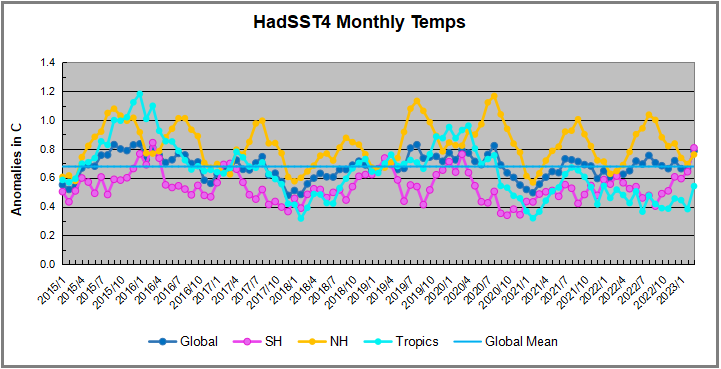

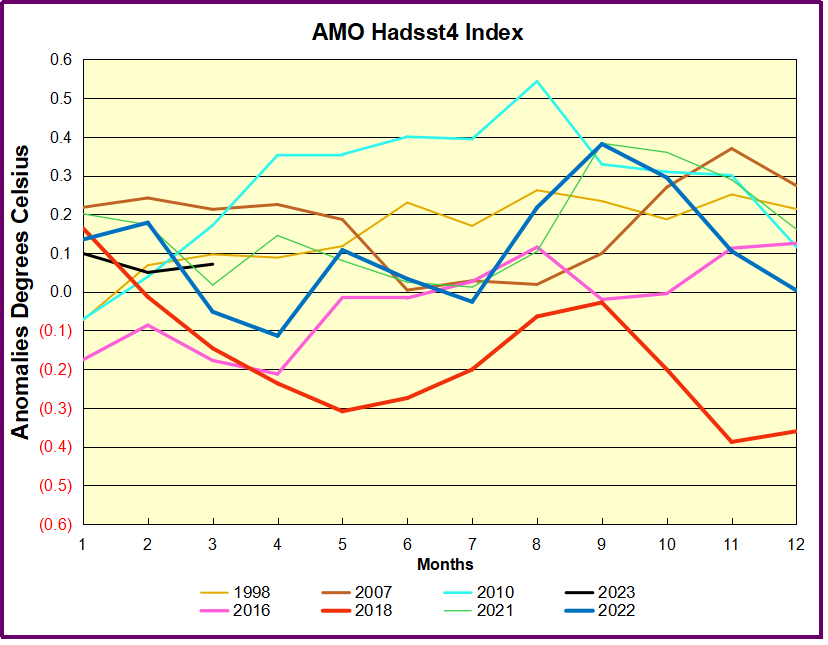

Note the difference between blue/green years, beige/brown, and purple/red years. 2010, 2021, 2022 all peaked strongly in August or September. 1998 and 2007 were mildly warm. 2016 and 2018 were matching or cooler than the global average. 2023 is starting out slightly warm.

The background post below provides more detail on AMO and AMOC measuring systems, but there is a growing concern that funding for oceanic data is being reduced or cut off. For example this report from Srokosz et al. (2020):

Despite the tremendous progress in AMOC-related research as articulated in the Special Issue manuscripts, there are many remaining challenges that should be addressed to further our understanding. From the observational side, such challenges include gaps in the observing system (e.g., shelf regions and deep oceans), disparate observational strategies, and reductions in funding that jeopardize sustained observations (Frajka-Williams et al., 2019; McCarthy et al., 2020). Earth system models continue to show persistent biases, particularly in the North Atlantic, and AMOC variability mechanisms and their characteristics vary significantly across models (e.g., Danabasoglu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019).

Although the US AMOC Program formally “sunsets” in 2021, research on the AMOC in the United States will continue. The original motivation for AMOC observations, the possibility of AMOC decline or rapid collapse under anthropogenically induced climate change, remains. The latest IPCC special report on the ocean and cryosphere (Pörtner et al., 2019) states that “Observations, both in situ (2004–2017) and based on sea surface temperature reconstructions, indicate that the AMOC has weakened relative to 1850–1900 (medium confidence),” and that “The AMOC is projected to weaken in the 21st century under all RCPs (very likely), although a collapse is very unlikely (medium confidence).” These conclusions and the above challenges present new opportunities and motivations for the community. Specifically, collaborative research that includes a hierarchy of models, theory, high-resolution paleo records, and sustained and processed-based observations promises to advance our understanding, potentially leading to improved models and prediction skills, among others, of AMOC variability and its associated climate impacts.

Comment: It seems that data showing errors in the climate models, or failing to support climate alarm, will disappear when funding is withdrawn.

Background: AMOC Update: Oceans Moderate Climate Threat

Update Feb.1, 2019 New Publication from M.S. Lozier et al.

The article is A sea change in our view of overturning in the subpolar North Atlantic which is reporting on the first 21 months of observations from the newly installed OSNAP array described in a previous post from a year ago (reprinted below). The article is paywalled, but the main findings are provided at a Science Daily article European waters drive ocean overturning, key for regulating climate. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Summary:

An international study reveals the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, which helps regulate Earth’s climate, is highly variable and primarily driven by the conversion of warm, salty, shallow waters into colder, fresher, deep waters moving south through the Irminger and Iceland basins. This upends prevailing ideas and may help scientists better predict Arctic ice melt and future changes in the ocean’s ability to mitigate climate change by storing excess atmospheric carbon.

New research shows the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, which regulates climate, is primarily driven by waters west of Europe.

Credit: Carolina Nobre, WHOI Media

In a departure from the prevailing scientific view, the study shows that most of the overturning and variability is occurring not in the Labrador Sea off Canada, as past modeling studies have suggested, but in regions between Greenland and Scotland. There, warm, salty, shallow waters carried northward from the tropics by currents and wind, sink and convert into colder, fresher, deep waters moving southward through the Irminger and Iceland basins.

Overturning variability in this eastern section of the ocean was seven times greater than in the Labrador Sea, and it accounted for 88 percent of the total variance documented across the entire North Atlantic over the 21-month study period.

“Overturning carries vast amounts of anthropogenic carbon deep into the ocean, helping to slow global warming,” said co-author Penny Holliday of the National Oceanography Center in Southampton, U.K. “The largest reservoir of this anthropogenic carbon is in the North Atlantic.”

“Overturning also transports tropical heat northward,” Holliday said, “meaning any changes to it could have an impact on glaciers and Arctic sea ice. Understanding what is happening, and what may happen in the years to come, is vital.”

MIT’s Carl Wunsch and other outside experts said the study was helpful, but pointed out that 21 months of study is not enough to know if this different location is temporary or permanent.

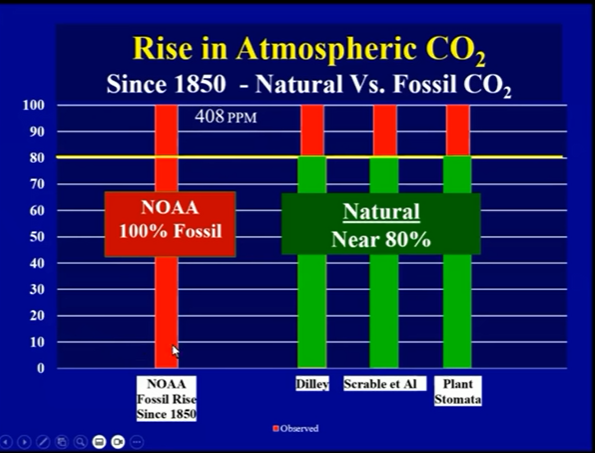

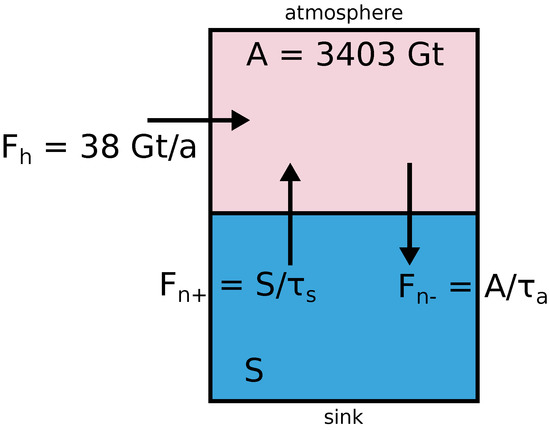

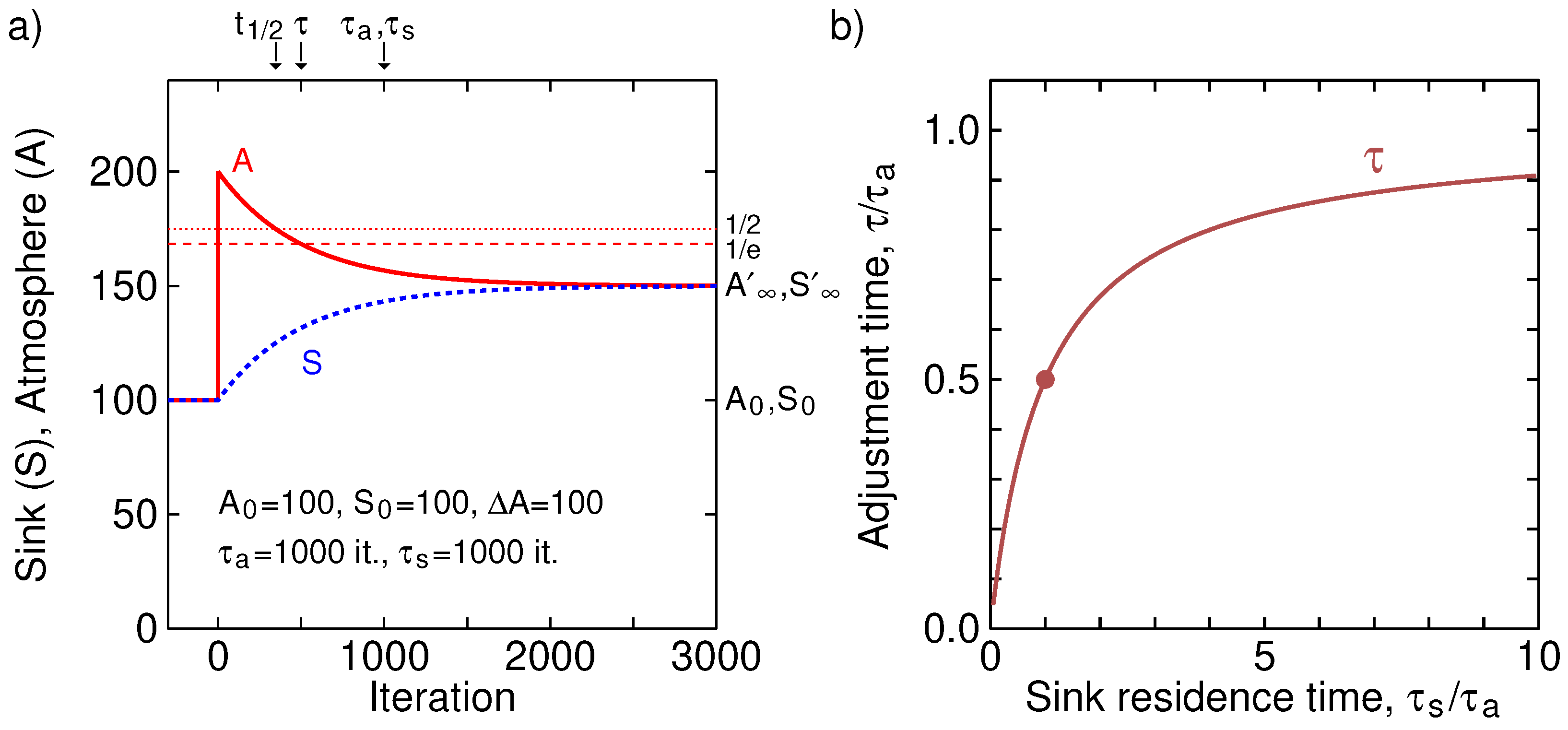

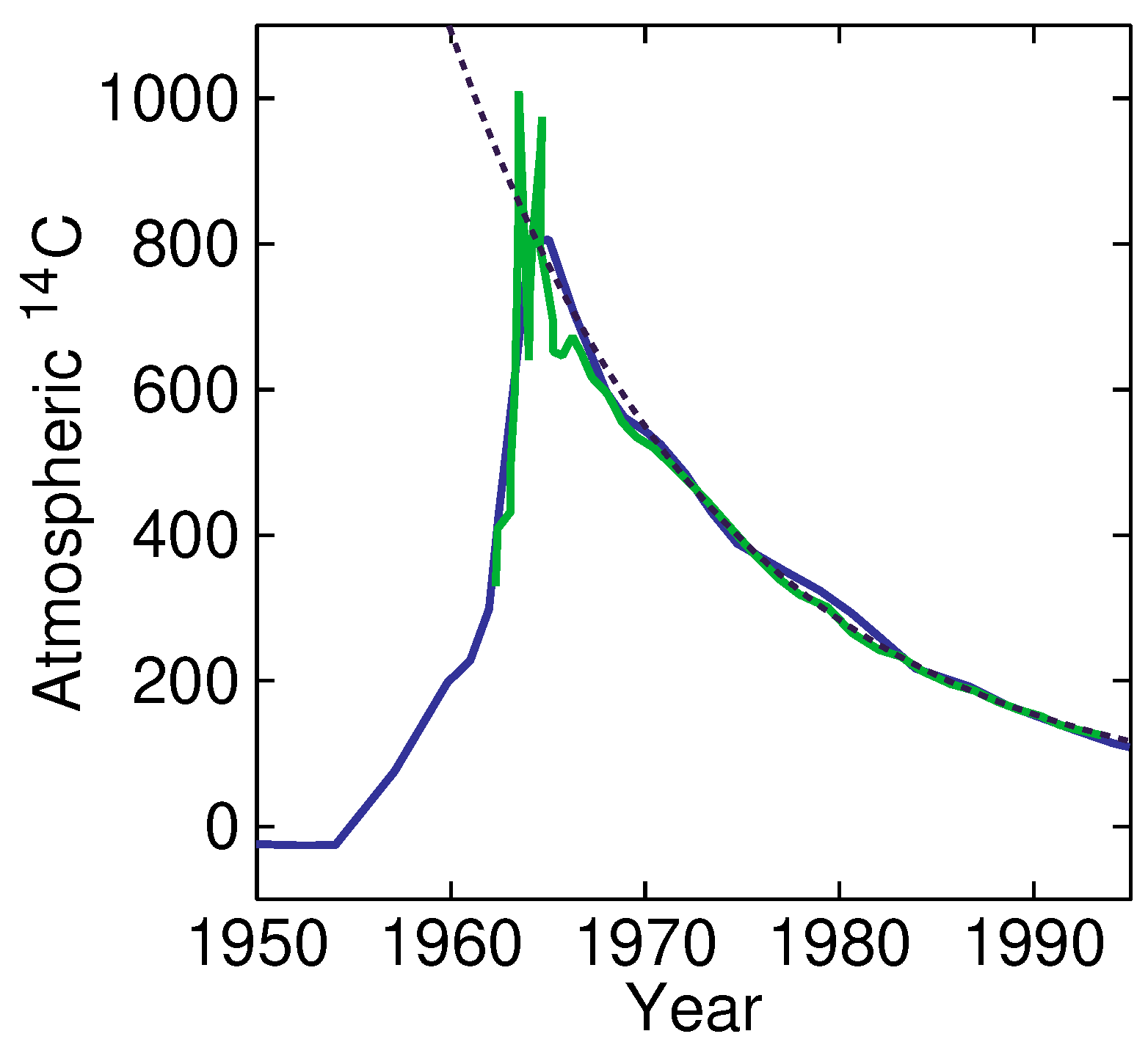

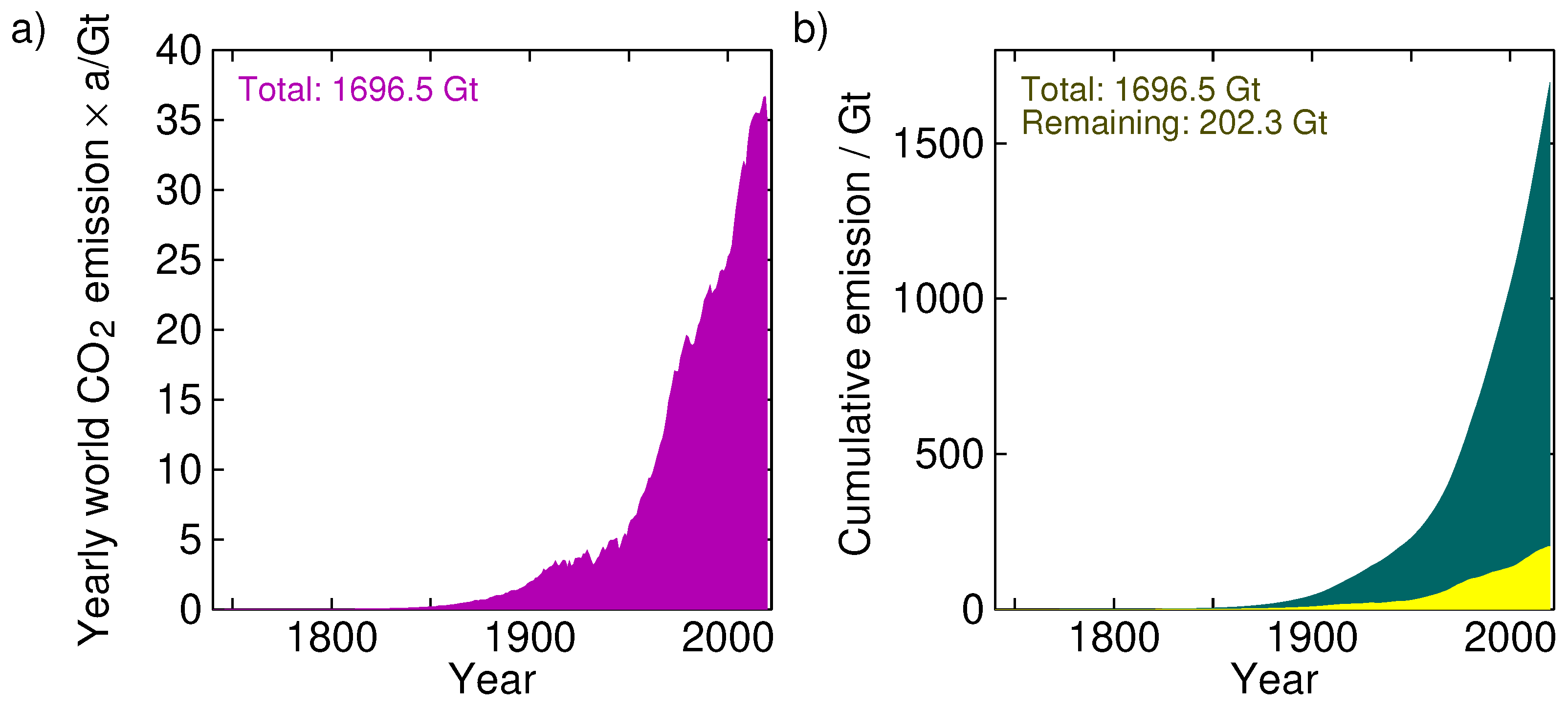

[Note: The comment about oceans taking up CO2 could be misleading. The ocean contains dissolved CO2 amounting to 50 times atmospheric CO2. Each year about 20% of all CO2 in the air goes into the ocean, replaced by outgassing CO2. The tiny fraction of atmospheric CO2 from humans is exchanged proportionately. Henry’s law applies to the water/air interface, so that a warmer ocean absorbs slightly less, and a colder ocean absorbs slightly more CO2. The exchange equilibrium is hardly disturbed by the little bit of human produced CO2. Thus the ocean serves as a massive buffer against human emissions.]

Previous Post: AMOC 2018: Not Showing Climate Threat

The RAPID moorings being deployed. Credit: National Oceanography Centre.

The AMOC is back in the news following a recent Ocean Sciences meeting. This update adds to the theme Oceans Make Climate. Background links are at the end, including one where chief alarmist M. Mann claims fossil fuel use will stop the ocean conveyor belt and bring a new ice age. Actual scientists are working away methodically on this part of the climate system, and are more level-headed. H/T GWPF for noticing the recent article in Science Ocean array alters view of Atlantic ‘conveyor belt’ By Katherine Kornei Feb. 17, 2018 . Excerpts with my bolds.

The powerful currents in the Atlantic, formally known as the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), are a major engine in Earth’s climate. The AMOC’s shallower limbs—which include the Gulf Stream—transport warm water from the tropics northward, warming Western Europe. In the north, the waters cool and sink, forming deeper limbs that transport the cold water back south—and sequester anthropogenic carbon in the process. This overturning is why the AMOC is sometimes called the Atlantic conveyor belt.

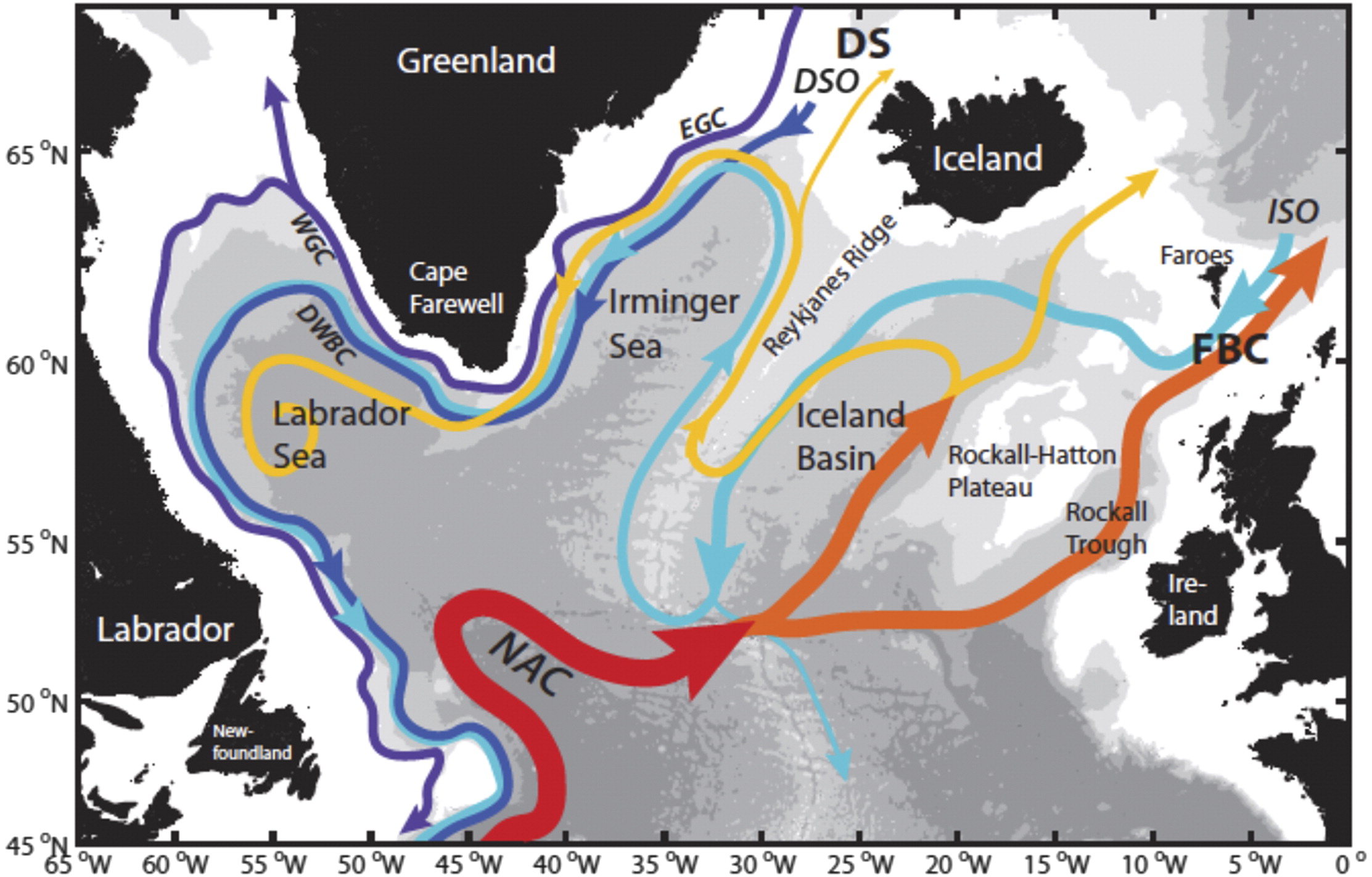

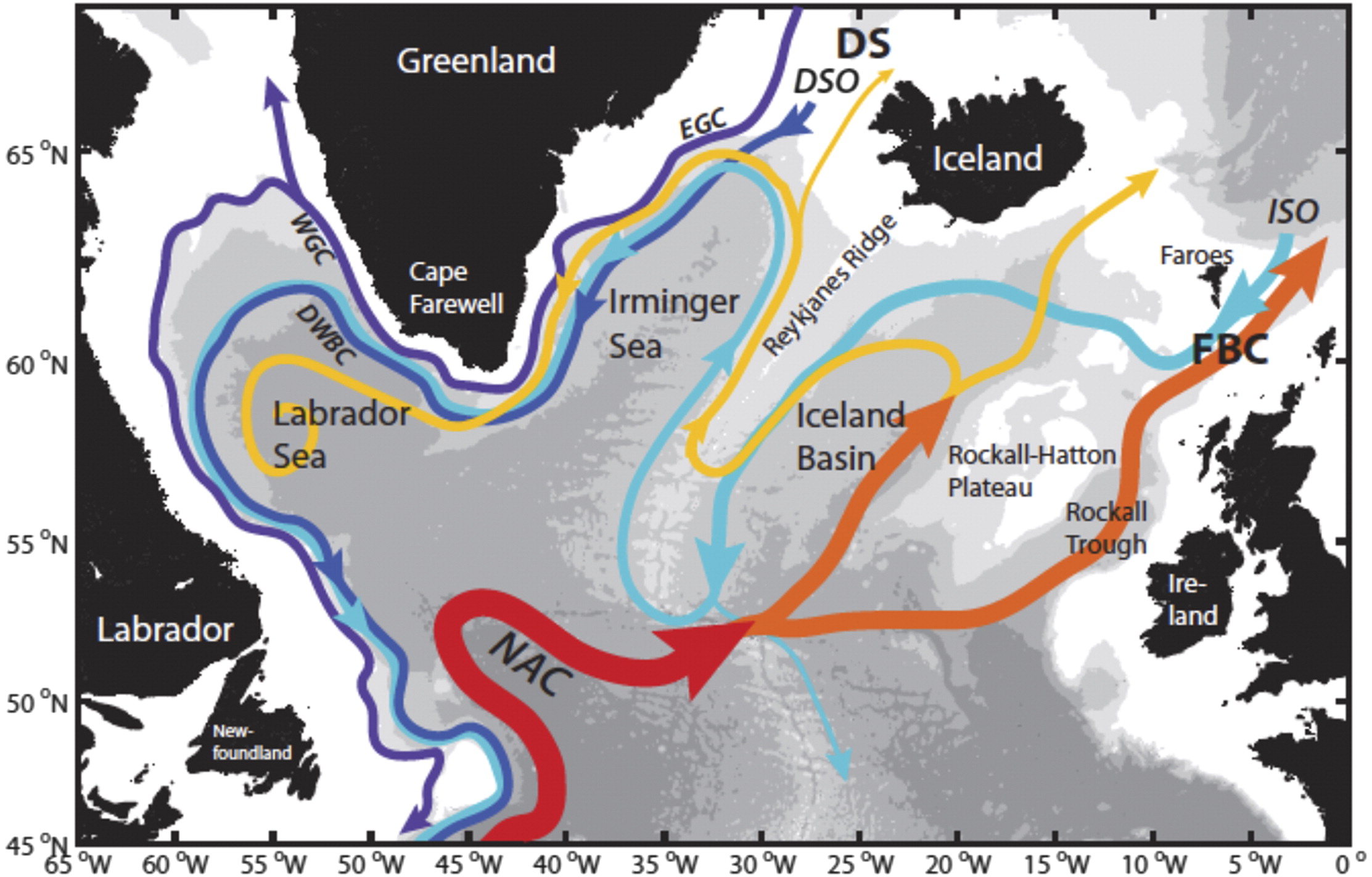

Fig. 1. Schematic of the major warm (red to yellow) and cold (blue to purple) water pathways in the NASPG (North Atlantic subpolar gyre ) credit: H. Furey, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution): Denmark Strait (DS), Faroe Bank Channel (FBC), East and West Greenland Currents (EGC and WGC, respectively), NAC, DSO, and ISO.

Last week, at the American Geophysical Union’s (AGU’s) Ocean Sciences meeting here, scientists presented the first data from an array of instruments moored in the subpolar North Atlantic. The observations reveal unexpected eddies and strong variability in the AMOC currents. They also show that the currents east of Greenland contribute the most to the total AMOC flow. Climate models, on the other hand, have emphasized the currents west of Greenland in the Labrador Sea. “We’re showing the shortcomings of climate models,” says Susan Lozier, a physical oceanographer at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who leads the $35-million, seven-nation project known as the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program (OSNAP).

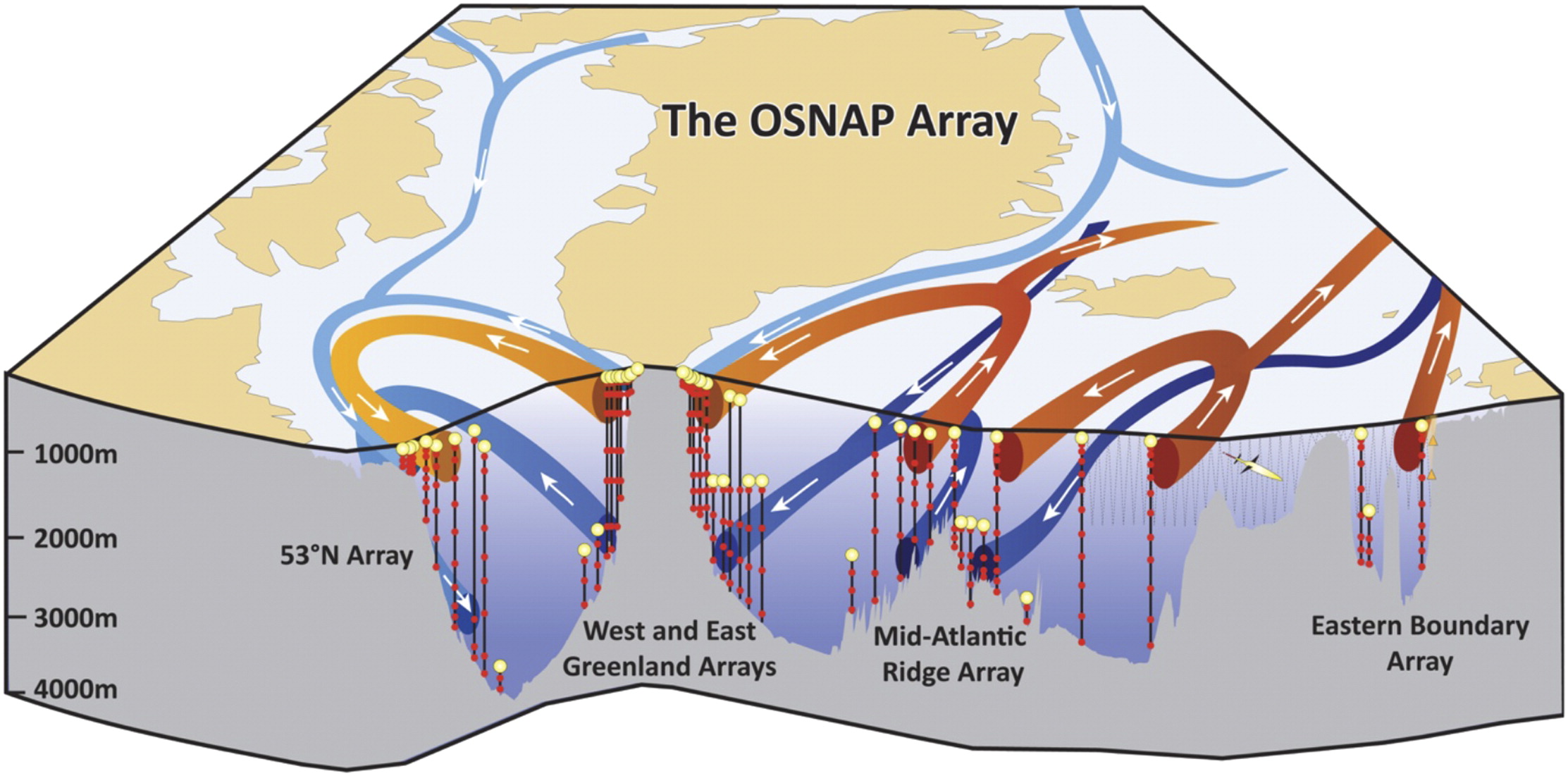

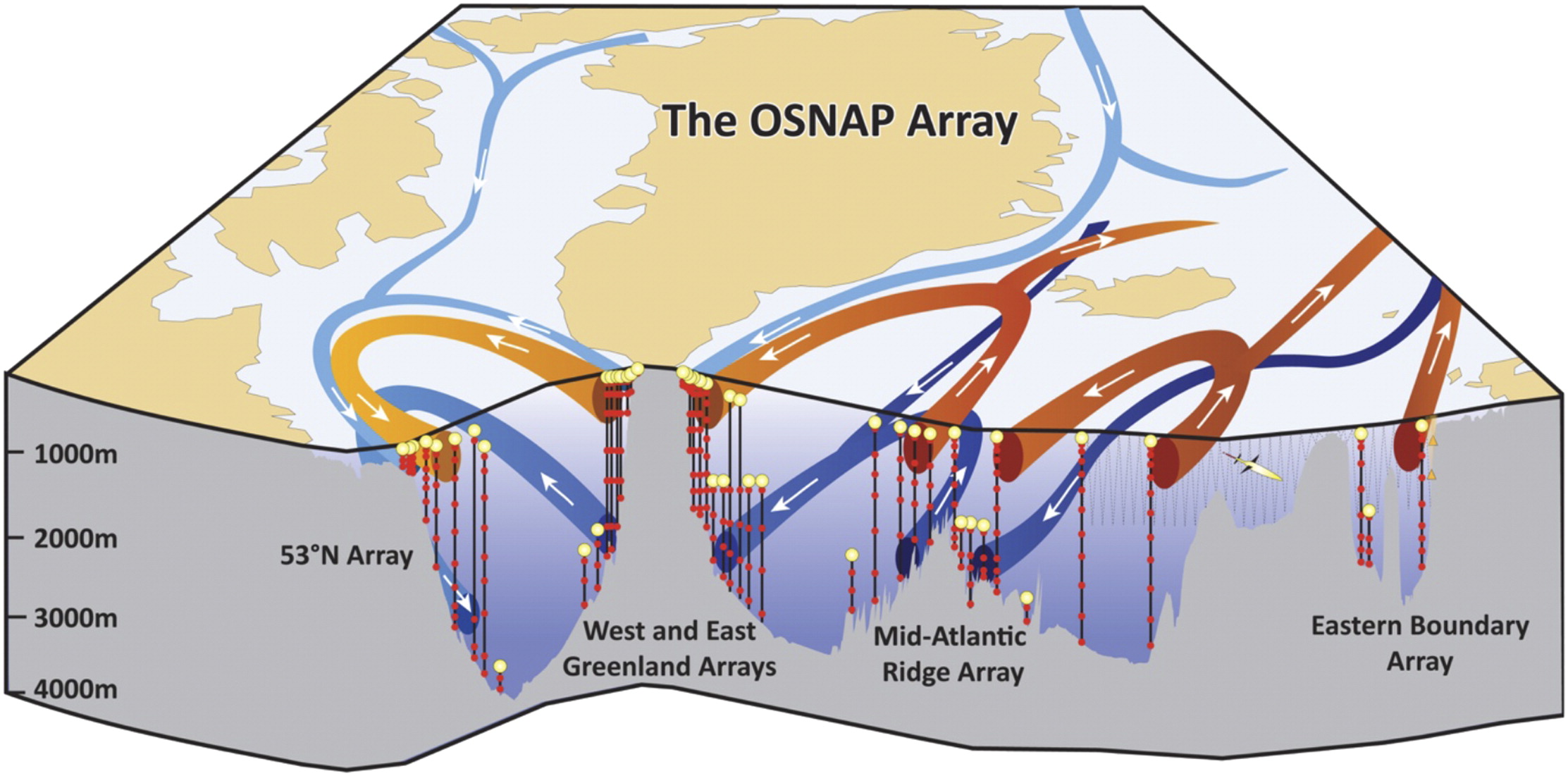

Fig. 2. Schematic of the OSNAP array. The vertical black lines denote the OSNAP moorings with the red dots denoting instrumentation at depth. The thin gray lines indicate the glider survey. The red arrows show pathways for the warm and salty waters of subtropical origin; the light blue arrows show the pathways for the fresh and cold surface waters of polar origin; and the dark blue arrows show the pathways at depth for waters that originate in the high-latitude North Atlantic and Arctic.

The research and analysis is presented by Dr. Lozier et al. in this publication Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program: A New International Ocean Observing System Images above and text excerpted below with my bolds.

For decades oceanographers have assumed the AMOC to be highly susceptible to changes in the production of deep waters at high latitudes in the North Atlantic. A new ocean observing system is now in place that will test that assumption. Early results from the OSNAP observational program reveal the complexity of the velocity field across the section and the dramatic increase in convective activity during the 2014/15 winter. Early results from the gliders that survey the eastern portion of the OSNAP line have illustrated the importance of these measurements for estimating meridional heat fluxes and for studying the evolution of Subpolar Mode Waters. Finally, numerical modeling data have been used to demonstrate the efficacy of a proxy AMOC measure based on a broader set of observational data, and an adjoint modeling approach has shown that measurements in the OSNAP region will aid our mechanistic understanding of the low-frequency variability of the AMOC in the subtropical North Atlantic.

Fig. 7. (a) Winter [Dec–Mar (DJFM)] mean NAO index. Time series of temperature from the (b) K1 and (c) K9 moorings.

Finally, we note that while a primary motivation for studying AMOC variability comes from its potential impact on the climate system, as mentioned above,

additional motivation for the measure of the heat, mass, and freshwater fluxes in the subpolar North Atlantic arises from their potential impact on marine biogeochemistry and the cryosphere. Thus, we hope that this observing system can serve the interests of the broader climate community.

Fig. 10. Linear sensitivity of the AMOC at (d),(e) 25°N and (b),(c) 50°N in Jan to surface heat flux anomalies per unit area. Positive sensitivity indicates that ocean cooling leads to an increased AMOC—e.g., in the upper panels, a unit increase in heat flux out of the ocean at a given location will change the AMOC at (d) 25°N or (e) 50°N 3 yr later by the amount shown in the color bar. The contour intervals are logarithmic. (a) The time series show linear sensitivity of the AMOC at 25°N (blue) and 50°N (green) to heat fluxes integrated over the subpolar gyre (black box with surface area of ∼6.7 × 10 m2) as a function of forcing lead time. The reader is referred to Pillar et al. (2016) for model details and to Heimbach et al. (2011) and Pillar et al. (2016) for a full description of the methodology and discussion relating to the dynamical interpretation of the sensitivity distributions.

In summary, while modeling studies have suggested a linkage between deep-water mass formation and AMOC variability, observations to date have been spatially or temporally compromised and therefore insufficient either to support or to rule out this connection.

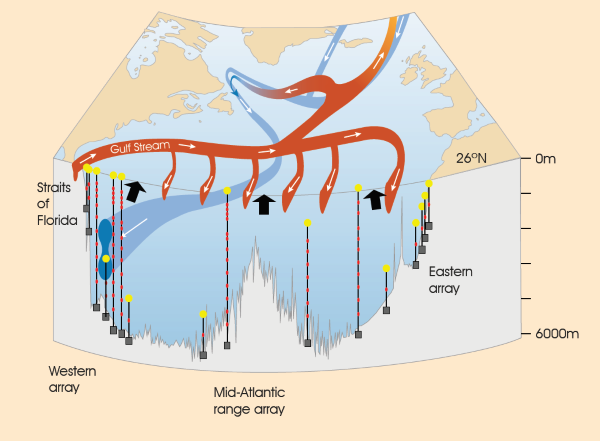

Current observational efforts to assess AMOC variability in the North Atlantic.

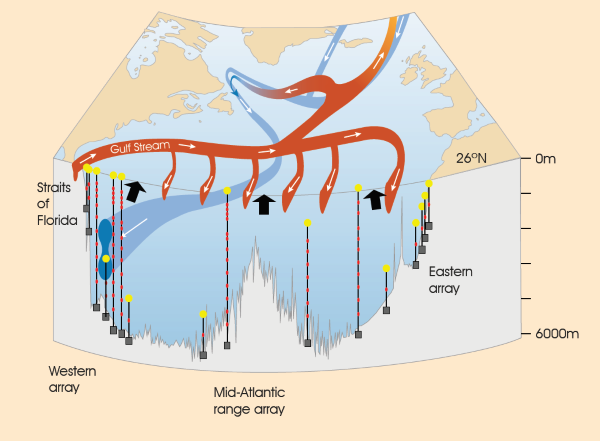

The U.K.–U.S. Rapid Climate Change–Meridional Overturning Circulation and Heatflux Array (RAPID–MOCHA) program at 26°N successfully measures the AMOC in the subtropical North Atlantic via a transbasin observing system (Cunningham et al. 2007; Kanzow et al. 2007; McCarthy et al. 2015). While this array has fundamentally altered the community’s view of the AMOC, modeling studies over the past few years have suggested that AMOC fluctuations on interannual time scales are coherent only over limited meridional distances. In particular, a break point in coherence may occur at the subpolar–subtropical gyre boundary in the North Atlantic (Bingham et al. 2007; Baehr et al. 2009). Furthermore, a recent modeling study has suggested that the low-frequency variability of the RAPID–MOCHA appears to be an integrated response to buoyancy forcing over the subpolar gyre (Pillar et al. 2016). Thus, a measure of the overturning in the subpolar basin contemporaneous with a measure of the buoyancy forcing in that basin likely offers the best possibility of understanding the mechanisms that underpin AMOC variability. Finally, though it might be expected that the plethora of measurements from the North Atlantic would be sufficient to constrain a measure of the AMOC within the context of an ocean general circulation model, recent studies (Cunningham and Marsh 2010; Karspeck et al. 2015) reveal that there is currently no consensus on the strength or variability of the AMOC in assimilation/reanalysis products.

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). Red colours indicate warm, shallow currents and blue colours indicate cold, deep return flows. Modified from Church, 2007, A change in circulation? Science, 317(5840), 908–909. doi:10.1126/science.1147796

In addition we have a recent report from the United Kingdom Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership (MCCIP) lead author G.D. McCarthy Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) 2017.

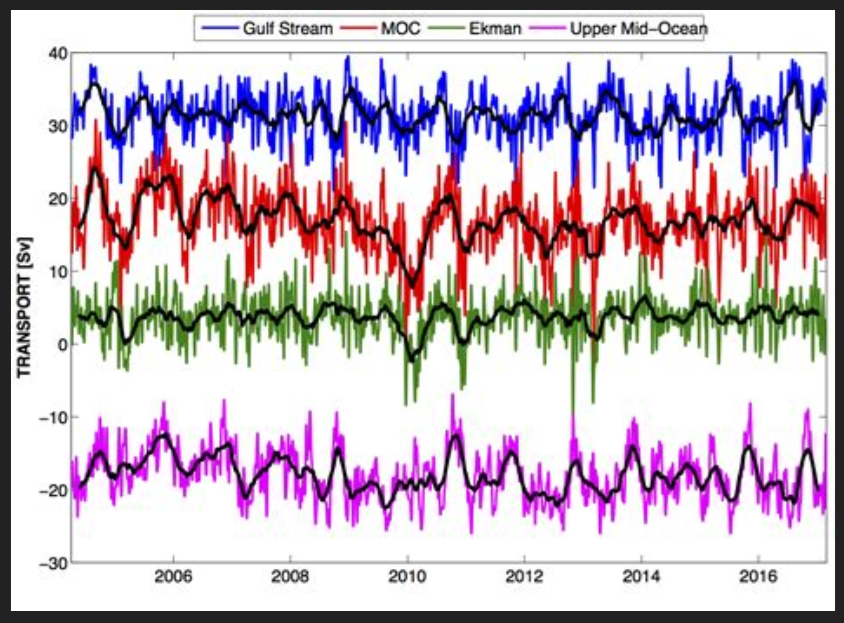

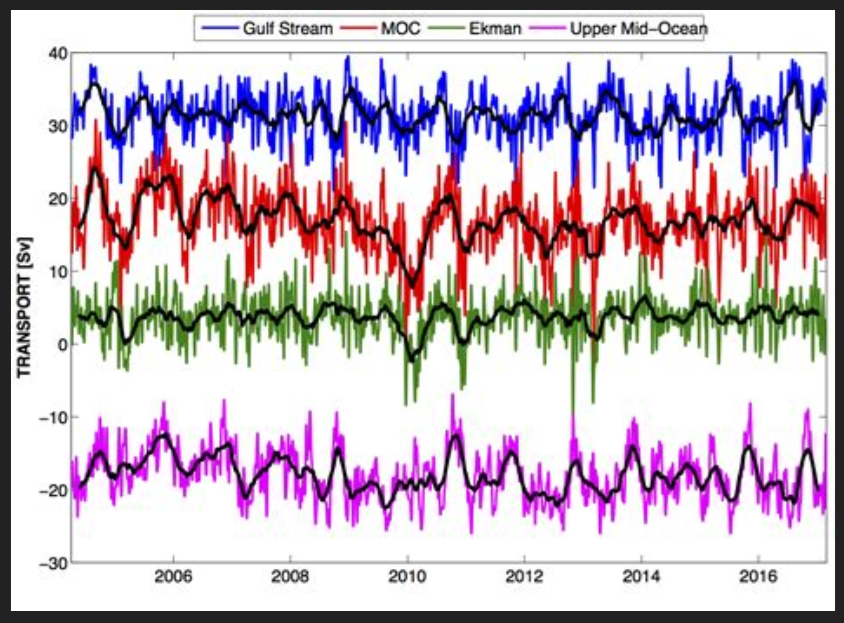

Figure 1: Ten-day (colours) and three month (black) low-pass filtered timeseries of Florida Straits transport (blue), Ekman transport (green), upper mid-ocean transport (magenta), and overturning transport (red) for the period 2nd April 2004 to end- February 2017. Florida Straits transport is based on electromagnetic cable measurements; Ekman transport is based on ERA winds. The upper mid-ocean transport, based on the RAPID mooring data, is the vertical integral of the transport per unit depth down to the deepest northward velocity (~1100 m) on each day. Overturning transport is then the sum of the Florida Straits, Ekman, and upper mid-ocean transports and represents the maximum northward transport of upper-layer waters on each day. Positive transports correspond to northward flow.

The RAPID/MOCHA/WBTS array (hereinafter referred to as the RAPID array) has revolutionized basin scale oceanography by supplying continuous estimates of the meridional overturning transport (McCarthy et al., 2015), and the associated basin-wide transports of heat (Johns et al., 2011) and freshwater (McDonagh et al., 2015) at 10-day temporal resolution. These estimates have been used in a wide variety of studies characterizing temporal variability of the North Atlantic Ocean, for instance establishing a decline in the AMOC between 2004 and 2013.

Summary from RAPID data analysis

MCCIP reported in 2006 that:

- a 30% decline in the AMOC has been observed since the early 1990s based on a limited number of observations. There is a lack of certainty and consensus concerning the trend;

- most climate models anticipate some reduction in strength of the AMOC over the 21st century due to increased freshwater influence in high latitudes. The IPCC project a slowdown in the overturning circulation rather than a dramatic collapse.

- And in 2017 that:

- a substantial increase in the observations available to estimate the strength of the AMOC indicate, with greater certainty, a decline since the mid 2000s;

- the AMOC is still expected to decline throughout the 21st century in response to a changing climate. If and when a collapse in the AMOC is possible is still open to debate, but it is not thought likely to happen this century.

And also that:

- a high level of variability in the AMOC strength has been observed, and short term fluctuations have had unexpected impacts, including severe winters and abrupt sea-level rise;

- recent changes in the AMOC may be driving the cooling of Atlantic ocean surface waters which could lead to drier summers in the UK.

Conclusions

- The AMOC is key to maintaining the mild climate of the UK and Europe.

- The AMOC is predicted to decline in the 21st century in response to a changing climate.

- Past abrupt changes in the AMOC have had dramatic climate consequences.

- There is growing evidence that the AMOC has been declining for at least a decade, pushing the Atlantic Multidecadal Variability into a cool phase.

- Short term fluctuations in the AMOC have proved to have unexpected impacts, including being linked

with severe winters and abrupt sea-level rise.

Background:

Climate Pacemaker: The AMOC

Evidence is Mounting: Oceans Make Climate

Mann-made Global Cooling