Let Them Eat Steak!

Will Coggin writes at USA Today Let them eat steak: Hold the shame, Red meat is not bad for you or the climate. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and images.

Plant-based meat may enjoy the perception of being healthier than real meat, but it has more sodium and calories and can cause weight gain.

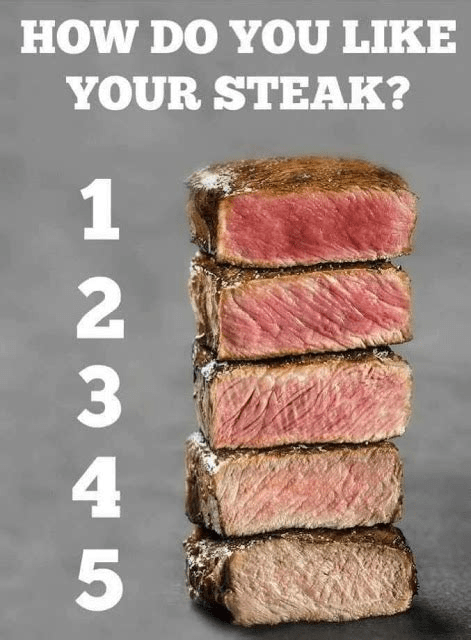

Imagine ordering dinner at your favorite restaurant. You know what you want without hesitation: a perfectly marbled 8-ounce steak cooked medium rare. Just before you order, your date tells you they’ve read that cows cause climate change and that meat might be unhealthy. Suddenly, the Caesar salad seems like a better option.

We’ve all been steak-shamed before. Ever since Sen. George McGovern’s 1977 Dietary Goals report declared red meat a health villain, Americans have been chided out of eating red meat. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, red meat consumption has fallen more than 24% since 1976. During that time, study after study has attempted to tie red meat to a laundry list of health problems. Until now.

So many studies, so many flaws

Three studies published recently in the Annals of Internal Medicine did something too few papers do: Ask whether the previous studies had any meat on their bones. The researchers who wrote the report analyzed 61 past studies consisting of over 4 million participants to see whether red meat affected the risk of developing heart disease and cancer.

All three came to the same conclusion: Decreasing red meat consumption had little to no effect on reducing risk of heart disease, cancer or stroke.

How can so many studies be wrong?

Nutritional research often relies on survey-based observational studies. These track groups of people and the food they eat, or try to tie a person’s past eating habits to a person’s current state of health. The result is something akin to a crime chart from a mob movie with a random red string connecting random suspects trying to figure out “who dunnit.”

Observational studies rely on participants to recall past meals, sometimes as far back as a month. Even when eating habits are tracked in real time using food diaries, issues arise. Research has shown that participants don’t give honest answers and often pad food diaries with typically “good” foods like vegetables while leaving out things like meat, sweets and alcohol. There’s also the matter of having to accurately report portion sizes and knowing the ingredients of the food eaten in restaurants.

Beef may be healthier than fake meat

The room for error is huge. A much better form of study would be to lock people in cells for a period of time so that you could precisely control what they ate and did and then measure outcomes. Obviously, there are ethical issues with such a structure, which is why observational studies are more common, if flawed.

Some companies like Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat have tried to cash in on the misconception about meat’s healthfulness. According to the market research firm Mintel, 46% of Americans believe that plant-based meat is better for you than real meat. Ironically, the anti-meat messages could be leading people to less healthful options.

Science on your side: Don’t let vegetarian environmentalists shame you on meat

Plant-based meat might enjoy the perception of being healthier, but that perception is far from reality. A lean beef burger has an average of nearly 20% fewer calories and 80% less sodium than the two most popularfake-meat burgers, the Impossible Burger and the Beyond Burger.

Fake meat is also an “ultra-processed” food, filled with unpronounceable ingredients. The National Institutes of Health released a study in May finding that ultra-processed foods cause weight gain. Unlike observational studies, this research was a controlled, randomized study.

Earth will survive your meat-eating

It’s not just the flawed health claims about red meat that deserve a second look. In recent years, we’ve been told reducing meat consumption is essential to saving the planet. But despite what critics say, even if everyone in America went vegan overnight, total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) in the United States would only be reduced 2.6%.

Eat better meat:Don’t go vegan to save the planet. You can help by being a better meat-eater.

Since the early 1960s, America has shrank GHG emissions from livestock by 11.3% while doubling the production of animal farming. Meat production is a relatively minor contributor to our overall GHG levels. In other countries, it may have a higher impact. The solution is not lecturing everyone else to go meat-free. Sharing our advancements would prove to be a more likely and efficient way to reduce emissions than cutting out meat or replacing it with an ultra-processed analogue.

Those who enjoy a good steak now have a good retort the next time they’re criticized for their choice: Don’t have a cow.

While the responsible media like the New York Times and The Economist admitted to uncertainty–which given the complexity of the issue, was sensible—others cited the “irrefutable fact that oil resources are finite and declining” apparently unaware that oil is renewable, generated from organic material by geophysical processes, albeit very slowly.

While the responsible media like the New York Times and The Economist admitted to uncertainty–which given the complexity of the issue, was sensible—others cited the “irrefutable fact that oil resources are finite and declining” apparently unaware that oil is renewable, generated from organic material by geophysical processes, albeit very slowly.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65243326/1.0.jpg)