More Covid Truth Escapes the Fog

Matt Ridley writes at the Spectator We know everything – and nothing – about Covid. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Matt Ridley writes at the Spectator We know everything – and nothing – about Covid. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

It is data, not modelling, that we need now

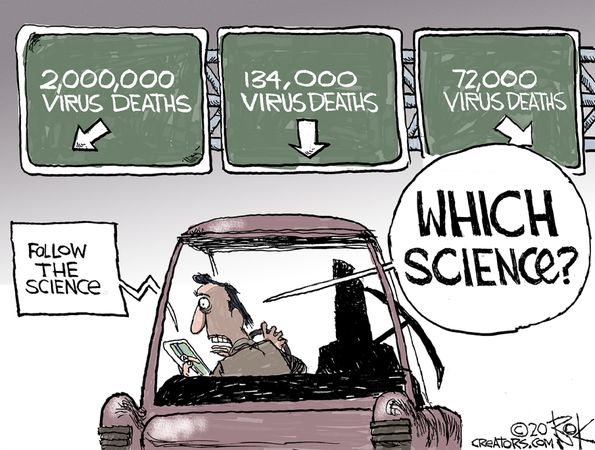

We know everything about Sars-CoV-2 and nothing about it. We can read every one of the (on average) 29,903 letters in its genome and know exactly how its 15 genes are transcribed into instructions to make which proteins. But we cannot figure out how it is spreading in enough detail to tell which parts of the lockdown of society are necessary and which are futile. Several months into the crisis we are still groping through a fog of ignorance and making mistakes. There is no such thing as ‘the science’.

This is not surprising or shameful; ignorance is the natural state of things. Every new disease is different and its epidemiology becomes clear only gradually and in retrospect. Is Covid-19 transmitted mainly by breath or by touching? Do children pass it on without getting sick? Why is it so much worse in Britain than Japan? Why are obese people especially at risk? How many people have had it? Are ventilators useless after all? Why is it not exploding in India and Africa? Will there be a second wave? We do not begin to have answers to these questions.

There is one vital fact that emerges from the fog. Countries that did a lot of testing from the start have fared much better than countries that did little testing. This is true not just of many Asian countries, such as South Korea (though Japan is an exception), but within Europe too. Up to the middle of last month, Iceland, Lithuania, Estonia and Germany had done many more tests per million people and recorded many fewer deaths per million people than Belgium, Britain, Italy and Sweden. As Max Roser of the website Our World In Data puts it: ‘The countries with the highest death rates got there by having the lowest testing rates.’

Yet it is not obvious why testing would make a difference, especially to the death rate. Testing does not cure the disease. Germany’s strange achievement of a consistently low case fatality rate seems baffling — until you think through where most early cases were found: in hospitals. By doing a lot more testing, countries like Germany might have partly kept the virus from spreading within the healthcare system. Germany, Japan and Hong Kong had different and more effective protocols in place from day one to prevent the virus spreading within care homes and hospitals.

The horrible truth is that it now looks like in many of the early cases, the disease was probably caught in hospitals and doctors’ surgeries.

That is where the virus kept returning, in the lungs of sick people, and that is where the next person often caught it, including plenty of healthcare workers. Many of these may not have realised they had it, or thought they had a mild cold. They then gave it to yet more elderly patients who were in hospital for other reasons, some of whom were sent back to care homes when the National Health Service made space on the wards for the expected wave of coronavirus patients.

The evidence from both Wuhan and Italy suggests that it was in healthcare settings, among the elderly and frail, that the epidemic was first amplified. But the Chinese authorities were then careful to quarantine those who tested positive in special facilities, keeping them away from the hospitals, and this may have been crucial. In Britain, the data shows that the vast majority of people in hospital with Covid-19 at every stage have been ‘inpatients newly diagnosed’; relatively few were ‘confirmed at the time of admission’. The assumption has been that most of the first group had been admitted on an earlier day with Covid symptoms. But maybe a lot of them had come to hospital with something else and then got the virus.

Even if you combine both groups, there are hardly enough admissions to explain the number of deaths in hospitals, unless nearly everybody admitted to hospital with Covid has died. It is likely that the frail and elderly, which the virus singles out for punishment, were more likely to be going to hospitals or clinics for other ailments and it was there that many of them got infected during February and March.

If Covid-19 is at least partly a ‘nosocomial’ (hospital-acquired) disease, then the pandemic might burn itself out quicker than expected.

The death rate here peaked on 8 April, just two weeks after lockdown began, which is surprisingly early given that it is usually at least four weeks after infection that people die if they die. But it makes sense if this was the fading of the initial, hospital–acquired wave. If you look at the per capita numbers for different countries in Europe, they all show a dampening of the rate of growth earlier than you would expect from the lockdowns.

This idea could be wrong, of course: as I keep saying, we just don’t know enough. But if it is right, it drives a coach and horses through the assumptions of the Imperial College model, on which policy decisions were hung. The famous ‘R’ (R0 at the start), or reproductive rate of the virus, could have been very high in hospitals and care homes, and much lower in the community. It makes no sense to talk of a single number for the whole of society. The simplistic Imperial College model, which spread around the world like a virus, should be buried. It is data, not modelling, that we need now.

If the elderly, obese and frail are not just at greater risk of dying, but also more susceptible and more infectious, then by definition everybody else is less so.

Gabriela Gomes and colleagues at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine looked at what would happen if the susceptibility of different segments of the population to the virus is very different, and concluded that in some circumstances effective herd immunity could be achieved with as little as 10 per cent of the population immunised. In the words of the study: ‘Individuals that are frailer, and therefore more susceptible or more exposed, have higher probabilities of being infected, depleting the susceptible subpopulation of those who are at higher risk of infection, and thus intensifying the deceleration in occurrence of new cases.’

If this is right, then it is good news. Once the epidemic is under control in hospitals and care homes, the disease might die out anyway, even without lockdown. In sharp contrast to the pattern among the elderly, children do not transmit the virus much if at all. This makes models based on flu, a disease that hits the young hard, misleading. The more the coronavirus has to use younger people to get around, the weaker its chances of surviving. Summer sunlight should slow it further, both by killing the virus directly and by boosting vitamin D levels.

It won’t be straightforward and there will be setbacks, but testing, followed by track and trace, is plainly now the way out. Britain is belatedly catching up. Matt Hancock’s ambitious dare to the healthcare system to get to 100,000 tests a day had the desired effect. We are now brimming with testing capacity, albeit still too centralised and slow in getting results back to people.

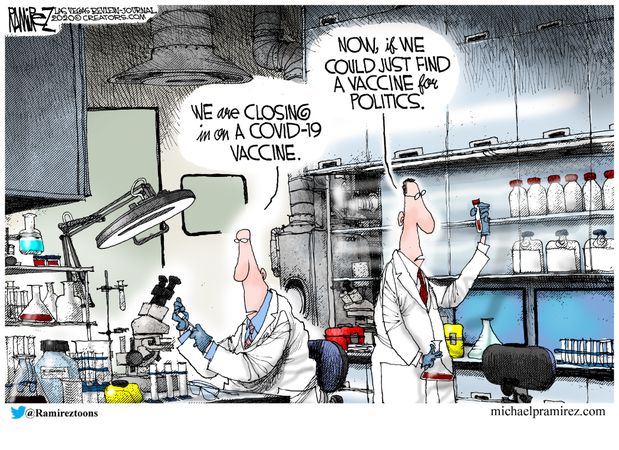

In the light of what we know, it is vital that the government now switches from urging us to stay at home to urging us to return to as much of normal life as possible. Be in no doubt that the strangulation that is asphyxiating the economy will have to be gradually lifted long before we know the full epidemiology of the virus.

Perilous though the path is, we cannot wait for the fog to lift before we start down the mountain.