Jon Entine writes again lamenting false alarms by scientists and journalists The Insect Apocalypse That Never Was. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Jon Entine writes again lamenting false alarms by scientists and journalists The Insect Apocalypse That Never Was. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

For the past four years, journalists and environmental bloggers have been churning out alarming stories that insects are vanishing, in the United States and globally. Limited available evidence lends credence to reasonable concerns, not least because insects are crucial components of many ecosystems. But the issue has often been framed in catastrophic terms, with predictions of a near-inevitable and imminent ecological collapse that would break ecosystems, destroy harvests, and trigger widespread starvation. Most of the proposed solutions would require a dramatic retooling of many aspects of modern life, from urbanization to agriculture.

Considering the disruptive economic and social trade-offs being demanded by some of those promoting the crisis hypothesis, it’s prudent to separate genuine threats from agenda-driven hyperbole. Are insect declines really threatening to precipitate a catastrophic ecological crisis? And, given the available data, what should a responsible society be doing?

The silver lining around the cloud of gloomy advocacy-focused studies and reporting is that entomologists are doing a deeper dive into the reasons behind the global declines. Goulson’s upcoming media blitz notwithstanding, the most thorough studies to date on insects in North America challenge the catastrophe narrative (although you may not have heard about them as they have been almost ignored by the media), and even offers some reassuring news.

The Moran study, published last August, specifically examined four to 36 years of data on arthropods (insects and other invertebrates) collected from US Long-Term Ecological Research sites located in ecoregions throughout the country. The authors found that: “There is no evidence of precipitous and widespread insect abundance declines in North America akin to those reported from some sites in Europe.”

The robustness of the Moran study data suggests the insect population story is much more complicated—and less dire—than many headlines suggest. If a thorough examination of the data on one continent can lead to such a dramatically different and more hopeful conclusion, broad trends in the vast, highly diverse, and relatively unstudied continents of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Australia cannot be characterized through extrapolation with any assurance.

The overall paucity of data provides an opening for alarmists to speculate, and Goulson and others have taken advantage of that. But why are the data so fragmentary? Moran attributed the lack of corroborating studies supporting the consensus view that insect populations are mostly stable to what he calls “publication bias … more dramatic results are more publishable. Reviewers and journals are more likely to be interested in species that are disappearing than in species that show no change over time,” he wrote in the Washington Post.

It’s a reinforcing feedback loop, with journalists playing a key role in this misinformation cycle. Scientific publications are more likely to publish reports of declining species. Then, when researchers search for data, “declines are what they find.” The media often seize on incomplete or even biased conclusions to build a compelling narrative—an insect apocalypse or insectageddon or zombie-like resurrections of debunked reports of birdpocalypses and beepocalypses.

Background previous post: Epic Media Science Fail: Fear Not Pollinator Collapse

Jon Entine returns to this topic writing at the Genetic Literacy Project: The world faces ‘pollinator collapse’? How and why the media get the science wrong time and again. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

As I and others have detailed in the Genetic Literacy Project and as other news organizations such as the Washington Post and Slate have outlined, the pollinator-collapse narrative has been relentless and mostly wrong for more than seven years now.

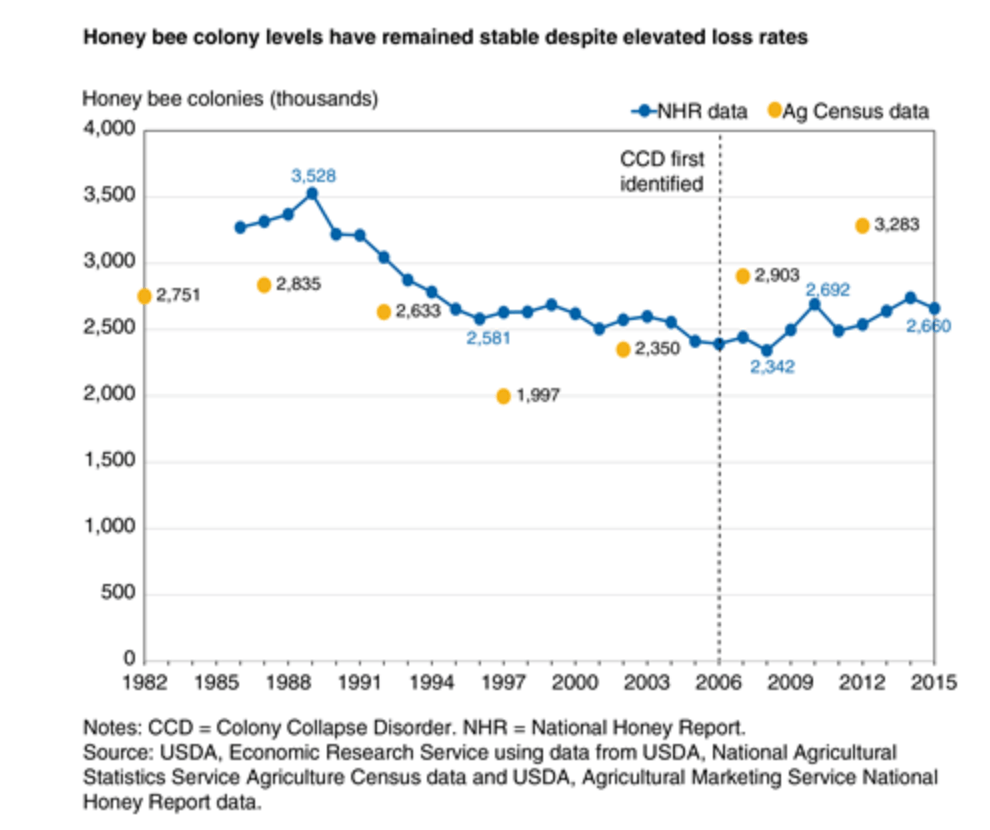

It germinated with Colony Collapse Disorder that began in 2006 and lasted for a few years—a freaky die off of bees that killed almost a quarter of the US honey bee population, but its cause remains unknown. Versions of CCD have been occurring periodically for hundreds of years, according to entomologists.

Today, almost all entomologists are convinced that the ongoing bee health crisis is primarily driven by the nasty Varroa destructor mite. Weakened honey bees, trucked around the country as livestock, face any number of health stressors along with Varroa, including the use of miticides used to control the invasive mite, changing weather and land and the use of some farm chemicals, which may lower the honeybee’s ability to fight off disease.

Still, the ‘bee crisis’ flew under the radar until 2012, when advocacy groups jumped in to provide an apocalyptic narrative after a severe winter led to a sharp, and as it turned out temporary, rise in overwinter bee deaths.

Colony loss numbers jumped in 2006 when CCD hit but have been steady and even improving since.

The alarm bells came with a spin, as advocacy groups blamed a class of pesticides known as neonicotinoids, which were introduced in the 1990s, well after the Varroa mite invasion infected hives and started the decline. The characterization was apocalyptic, with some activist claiming that neonics were driving honey bees to extinction.

In the lab evaluations, which are not considered state of the art—field evaluations replicate real-world conditions far better—honeybee mortality did increase. But that was also true of all the insecticides tested; after all, they are designed to kill harmful pests. Neonics are actually far safer than the pesticides they replaced, . . . particularly when their impact is observed under field-realistic conditions (i.e., the way farmers would actually apply the pesticide).

As the “science” supporting the bee-pocalypse came under scrutiny, the ‘world pollinator crisis’ narrative began to fray. Not only was it revealed that the initial experiments had severely overdosed the bees, but increasing numbers of high-quality field studies – which test how bees are actually affected under realistic conditions – found that bees can successfully forage on neonic-treated crops without noticeable harm.

Those determined to keep the crisis narrative alive were hardly deterred. Deprived of both facts and science to argue their case, many advocacy groups simply pounded the table by shifting their crisis argument dramatically. For example, in 2016, the Sierra Club (while requesting donations), hyped the honey bee crisis to no end.

But more recently, in 2018, the same organization posted a different message on its blog. Honeybees, the Sierra Club grudgingly acknowledged, were not threatened. Forget honeybees, the Sierra Club said, the problem is now wild bees, or more generally, all insect pollinators, which are facing extinction due to agricultural pesticides of all types (though neonics, they insisted, were especially bad).

So, once again, with neither the facts nor the science to back them up, advocacy groups have pulled a switcheroo and are again pounding the table. As they once claimed with honeybees, they now claim that the loss of wild bees and other insect pollinators imperils our food supply. A popular meme on this topic is the oft-cited statistic, which appears in the recent UN IPBES report on biodiversity, that “more than 75 per cent of global food crop types, including fruits and vegetables and some of the most important cash crops such as coffee, cocoa and almonds, rely on animal pollination.”

There’s a sleight of hand here. Most people (including most journalists) miss or gloss over the important point that this is 75 percent of crop types, or varieties, not 75 percent of all crop production. In fact, 60 percent of agricultural production comes from crops that do not rely on animal pollination, including cereals and root crops. As the GLP noted in its analysis, only about 7 percent of crop output is threatened by pollinator declines—not a welcomed percentage, but far from an apocalypse.

And the word “rely” seems almost purposefully misleading. More accurately, most of these crops receive some marginal boost in yield from pollination. Few actually “rely” on it. A UN IPBES report on pollinators published in 2018 actually breaks this down in a convenient pie graph.

Many of these facts are ignored by advocacy groups sharpening their axes, and they’re generally lost on the “if it bleeds it leads” media, which consistently play up catastrophe scenarios of crashing pollinator communities and food supplies. Unfortunately, many scientists willingly go along. Some are activists themselves; others hope to elevate the significance of their findings to garner media attention and supercharge grant proposals.

As John Adams is alleged to have said, ‘facts are stubborn things.’ We can’t be simultaneously in the midst of a pollinator crisis threatening our ability to grow food and see continually rising yield productivity among those crops most sensitive to pollination.

With these claims of an impending wild bee catastrophe, as in the case of the original honeybee-pocalypse claims, few of the journalists, activists, scientists or biodiversity experts who regularly sound this ecological alarm have reviewed the facts in context. Advocacy groups consistently extrapolate from the declines of a handful of wild bee species (out of the thousands that we know exist), to claim that we are in the midst of a worldwide crisis. But just as with the ‘honey bee-mageddon, we are not.

Those of us who actually care about science and fact, however, might note the irony here: It is precisely the pesticides which the catastrophists are urging us to ban that, along with the many other tools in the modern farmer’s kit, have enabled us grow more of these nutritious foods, at lower prices, than ever before in human history.

Footnote: Activists have played both sides with their insect warnings Alarmists: Global Warming Destroys Good Bugs and Multiplies Bad Bugs

Summary: These scares always sound plausible, but on closer inspection are simplistic and unrealistic. The above shows that each type of insect has a range of temperatures they can tolerate and allow them to develop. They are stressed and populations decrease when colder than the lower limit and also when hotter than the upper limit. Every species will adapt to changing conditions as they always have. Those at their upper limit will decline, not increase, and their place will be taken by others. Of course, if it gets colder, the opposite occurs. Don’t let them scare you that insects are taking over.

This article is really excellent work, Ron! You obviously put a lot of work into it, and I am grateful.

LikeLike

Thanks Dave. As you know, the false alarm industry never sleeps, and they return again and again to the themes of their crimes.

LikeLike

Whoops, how did I miss this?

Anyhow, it is terrific work, and I thank you, Ron, for bringing it to my attention.

LikeLike

Hi Ron

Been a while. I’ve got a question about the oxygen depleted oceans by 2030/40 article that appeared in Scientific America.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ocean-s-oxygen-starts-running-low/

The article is older dating to 2016.

Original paper

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2015GB005310

From what I could discern it’s based on a novel Earth system modeling approach to address the objectives.

I haven’t heard much about this scenario in the media but it still caught my attention.

What your short take on this?

Ray

LikeLike

Ray, here is a post I did after some research. IMO it is a real issue, and can best be addressed by better waste management

https://rclutz.com/2019/12/08/ocean-oxygen-misdirection-2/

LikeLike

Thanks Ron, I knew you must have had a post. I used you search tool but maybe I just didn’t use the right combination of words. The article refreshed my memory on the topic! I know there was something fishy about it.

Cheers R

LikeLike