Tom Nelson posted this interview with Ross McKitrick on Big problems with paleoclimate data and land temperature records. H/T Climate-Science.press.

Ross McKitrick is a Professor of Economics at the University of Guelph where he specializes in environment, energy and climate policy. He has published widely on the economics of pollution, climate change and public policy. His book Economic Analysis of Environmental Policy was published by the University of Toronto Press in 2010.

His background in applied statistics has also led him to collaborative work across a wide range of topics in the physical sciences including paleoclimate reconstruction, malaria transmission, surface temperature measurement and climate model evaluation.

Professor McKitrick has made many invited academic presentations around the world and has testified before the US Congress and committees of the Canadian House of Commons and Senate.

The discussion is wide-ranging, and I provide below a lightly edited transcript on the main theme, starting around minute 41. Text is in italics with my bolds and added images. TN refers to Tom Nelson’s comments and RM to Ross McKitrick.

Transcript

RM: People need to understand that for the 20th century as a whole there’s temperature data for less than 50 percent of the Earth’s surface. And a lot of stuff is just being filled in with with assumptions or or modeling work, so it’s really the output of models. And so as you go back in time back to the 1920s for instance, here in Southern Ontario we have great temperature records back to the 1920s. Here in Guelph we have temperature data that goes back to the late 1800s.

One of the first assignments I have my students do in my environmental economics courses is just to take a few locations in Ontario that have more than 100 Years of temperature data and plot the records for average daily highs back 100 years or more. That always surprises them because they just don’t see what they’re expecting to see in terms of an upward trend. There’s a visible trend up to the 1930s or so. And then after that it’s kind of up and down flat.

Summertime temperatures especially, have gone down, they’ve gone up,

but haven’t really changed much since the 1930s.

We happen to be in a part of the world where we’ve got those kinds of long temperature records. For the vast majority of the world there’s just no data at all, or there are short temperature records or fragments of temperature records over various intervals. Yet what we see are these temperature graphs going back to the 1860s that they call the observational record. There’s so many problems with those records, and unfortunately a lot of the problems are of the form that introduces an upward bias in the trend. And it’s very difficult to measure it and remove it, though I did some work on that I hope eventually to go and do some more.

TN I wish more people took an interest in that kind of topic. Have you followed the work of Tony Heller when he’s looking back at adjustments to cool the past. It seems pretty interesting.

RM: Yes. I’ve seen many of his videos and now he’s focusing on the U.S record in a lot of his videos. There I think the point that he conveys is how frustrating it is for an observer. Just this notion that you’ve got the raw temperature observations and then the adjustments and they all seem to pivot around 1960.

So that anything prior to 1960, the Adjustment goes down,

and anything after 1960 the Adjustment goes up.

They create this picture that somehow in 1960 everyone in the US knew how to measure temperature perfectly. So that’s the year we’re going to leave as it is, and prior to that everybody made the same mistake. Everybody was always overestimating temperature so we’ve got to adjust those records downward. Then ever since 1960 people haven’t known how to measure temperature so we have to raise those those measurements. The pattern of adjustment is so consistent in so many places in the U.S records that at a certain point it’s just on its face implausible that these adjustments are based on some objective algorithm.

I know the people who make the adjustments will say: Well we’ve got to deal with time of observation bias you know. But if these were the sort of standard measurement errors, you would expect a mix of positive and negative mistakes. Instead, there’s such a pattern to it. The adjustments account for all the warming.

When you look at the post-1960 U.S record the adjustments are as large as the warming itself.

Remember that the warming trend is such an important input into thinking about the policy. We really need to have absolute confidence in these adjustment processes, but the people who make the adjustments do not respond in a constructive and forthright fashion to these kinds of criticisms. In my experience, they instead take such offense that anyone would question what they’re doing. And they respond with abuse and indignation when perfectly reasonable questions are put to them.

That’s another thing that makes it frustrating to an outside observer looking at these these adjusted data sets. So Tony does a very effective job in letting people see: Okay, this is a graph you’re shown. This is what the data looked like when they first collected it, and this is what the observers wrote down. And then this is what it looks like after the adjustment process. Obviously, this whole warming Trend in the U.S record is coming through the adjustments. So we have a right to a very detailed and skeptical review of these adjustments. The the lack of constructive engagement on a question like that ignores that at a certain point, the burden of proof here is on you guys, the record keepers. It’s not on the people who look at the data to go into every station record and prove it’s wrong.

The burden of proof here is on the people making the adjustments. For a long time they would refer back to a paper that was done in the 1980s for the Department of energy by Tom Wigley as the scientific basis of the adjustments. Eventually I got a hold of that document (because it’s hard to find). It turned out it was really just a lot of: Okay we think this record here moved around 1925, they moved the station from here to there, so we’re gonna make a little few changes here and we’ll bump this stretch of the data set up by this amount. And so it wasn’t like a a detailed scientific methodology that you could subject to some testing and validation.

It was really and for the time, it was all anyone really would have expected: Which is go through the data set and discuss the potential flaws and what the ad hock adjustments were. But for a long time that was that was it as far as documenting the adjustments. Now I think they’ve got more information out online to help people understand it. But that’s a long answer to your question. I go back to point out the adjustment really matters for the overall conclusion. And so if we’re going to accept the conclusion, we need to have absolute confidence in these adjustments.

And the people who could have over the years helped us gain that kind of confidence

haven’t done so.

They’ve done the opposite by being so resistant to any questioning of of their work, and made it so difficult for people to critique it. In my experiences, when you do get stuff into print and journals, then the IPCC misrepresents it and even makes up stuff that isn’t true. So I’m quite sympathetic if people just want to dismiss the the adjusted temperature record as being the product of a process where people put their thumb on the scale to get a certain result.

TN: What do you think, do you have any predictions on where climate science is going in the next 10 or 20 years? Just more of the same, or is it eventually going to crumble? It just seems like this can’t keep going on, that the lies are so big that it can’t keep going on but what do you think?

RM: My observations began 20 years ago. When I started, if you think of where people are in the spectrum, you’ve got someone like me (whatever the opposite of the word alarmist would be). I’m not particularly worried about climate change. I think the evidence is: It’s not a big deal. And there’ll be changes and things to adapt to, but they’re on a small scale compared to the normal course of events and things that we we adapt to in life.

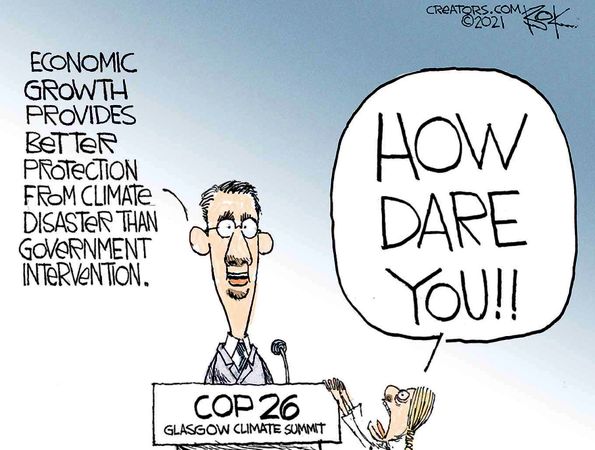

And then you’ve got the alarmists who are you know, throwing cans of soup at paintings and gluing themselves to the sidewalk and and having a complete emotional meltdown. In the early days the the IPCC was sort of on the alarmist camp over against the Skeptics, in the sense that they were the ones trying to pull everybody away from a viewpoint like the one I hold. It was: No, you guys have to be worried about this. Look at these charts and see what we got to be worried about.

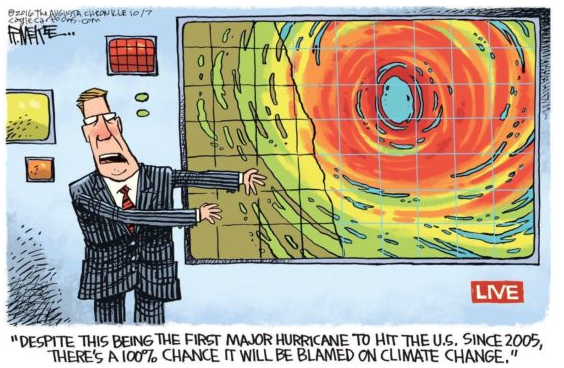

Now the alarm side has moved so far up the scale now that I think the IPCC is having to face the fact they have to begin to pull everybody back in you know my direction, our direction. So far, they’re not very good at that. Take for instance, discussions around hurricanes. You’ll get everybody from President Biden on down to some local weather caster on the the Channel 6 Nightly News confidently declaring that your tailpipe emissions caused hurricane Ian. And it’s your fault that all those homes are blown down. And you got the experts in places like NOAA and IPCC thinking: Oh we just put out a report that doesn’t say that that; in fact says the opposite. We don’t want to draw that connection and we can’t see a trend that would be consistent with that story.

But they say it in a very quiet heavily, coached language. For a long time they were happy to intervene early on when trying to fact check or, you know, counter messages from skeptics who were saying look this isn’t a big deal. They were happy to jump up and tell world leaders: No don’t listen to those guys, we tell you this is a big problem, blah blah blah.

Now they’ve got an even bigger problem with these crazy extremists saying all kinds of stuff that isn’t true and isn’t in their reports. What they should be doing is jumping up and saying to world leaders: Don’t listen to those guys, they’re nuts we we disavow that message. They’re not doing that and at this point they’re not yet capable of doing that.

Culturally within the IPCC, meaning the mainstream various branches such as the climate modeling groups, the atmospheric science groups and and oceanography groups. These are people that are all sort of comfortable with each other in terms of an overall set of assumptions. They may disagree on all kinds of other things, but culturally they’re comfortable with each other. And I think they’re all kind of looking at each other now and saying; Well, somebody’s got to stand up here and and say that’s not actually what we are arguing.

But nobody wants to do that; nobody wants to be the one to actually speak out. Look what happened when someone like Roger Pielke Jr said, Okay I’ll do it. I’ll stand up and and debunk some of the nonsense around hurricanes and extreme weather. Then what happens: They discover they’ve got so many extremists and activists in their own ranks who then attack a guy like Roger Pielke Jr. And that sends a message to the whole rest of the climate Community:

Don’t be like Roger Pielke Jr. Or you won’t get to eat lunch with the cool kids either.

So they’ve got this police network now in the climate field who make it impossible for them to stand up and and distance the field from the kooky extremists. It’s gonna take a long time for that to get sorted out, but I think there’s a few Milestones that are coming up quickly.

One is that 2030 will be an interesting year because first of all there will not have been any major reductions in CO2 emissions between now and 2030.

Well there were some during the Covid recession but things quickly return to trend. This year’s winter in Europe their CO2 emissions will go way down. Because they’re all going to freeze to death due to their stupid policy decisions that have left them without a reliable energy supply.

But any emission reductions taking place in the West are small and sporadic, and are more than offset by emission increases in China and India and places like that. As industry just leaves the crazy places like Europe and well, Canada unfortunately, places where energy is being made prohibitively expensive. Heavy industry is just packing up and moving somewhere else so by 2030 we won’t have done the emission reductions that the extreme alarmists have been calling for but at the same time we won’t have experienced the climate changes that they’ve been warning about.

In all this language that came out a couple of years ago, we have until 2030 to prevent extreme climate damages in the apocalyptic vision that they created. We’re going to get to 2030 and people will have seen the price that they paid for climate policy, they will have experienced the harm, experienced these winters that we’re in for. Europeans especially are in for the next couple of winters where they don’t have enough fossil energy sources to get through.

And just the cost of living effects of climate policy and 2030 will come

and we won’t have experienced climate Armageddon.

And they won’t be able to turn around and say: Well yeah, but we avoided it because we cut emissions because we didn’t cut emissions either. And so that’s where I would hope there’ll be a certain Reckoning and maybe some of it will have happened up to that point.

But heading to that point we still have the problem that there are lots of people that see this narrative as unsustainable. This whole ESG movement, the climate alarmist movement, isn’t sustainable since it doesn’t make sense. But then someone like Stuart Kirk at HSBC stood up, even though he thought he had approval from his higher ups to make a speech at a finance conference that said none of us really believe in climate alarmism. And he had this great line about the previous speaker said something to the effect of that by 2030 you’re all going to die from climate extremes and none of you even looked up from your phones.

“And so you don’t believe it, I don’t believe it, our clients don’t believe it.”

And soon after he got sacked.

So we’re still at the point where the sensible people, and they’re fortunately still many of them, sensible people in positions of influence don’t yet know how to talk about this. They don’t yet know how to pull the discussion back onto sensible grounds. I’ll return to the point I was making in the beginning: The IPCC were supposed to be the objective scientific thinkers who just call it straight. I think they found it easy in the early days when they felt like their job was to up the level of alarm above what the general public felt. Well now the public has leapfrogged them and and they’re all falling for these crazy alarmist extremes. Well it’s IPCC’s job to fix that.

But culturally within the IPCC and the climate science movement, I don’t think they’re able to do it. And the few people who try seem to get their heads bitten off.

It will eventually come back on the IPCC when when it becomes clear that the alarmist message was way over the top. People will be entitled at that point to say: Well this is your job to put a the brakes on this and straighten people out. And you didn’t do it so how can we trust you now?

TN: Are there any other points you’d like to make?

RM: Sometimes people wonder why would an economist presume to talk about these things?

It turns out climate science is a lot like economics in terms of the tools that people use. To a large extent it’s applied statistical analysis. And yes you have to know where your data comes from and you have to be able to interpret it. But the techniques are applied statistics and a lot of those techniques came out of econometrics or at least they came out of the same sources but a lot of the development of the technique has been in econometrics

It’s very hard for people in the climate field to follow those discussions because it’s a it’s econometrics it’s econometric Theory. I teach econometrics at the third year level and so I was just going through stuff I would expect my undergrads maybe the fourth year students to understand. But for a lot of people in the climate field you know this is the first time anyone’s really critiqued the theory behind that method.

It’s the kind of question Steve and I were asked with the Paleo climate stuff: Why are we doing this, why is why wasn’t it people in the field who noticed these flaws in the methods, who dug out the data figured out the method and pointed out the obvious flaws in it. So here I am 20 years after this technique was established I’m publishing a paper that says your fundamental results are invalid; you invoke the theorem incorrectly and your method does not generate unbiased and efficient results like you claimed. In fact it automatically fails the condition so you don’t know anything about what your results are.

TN: I was reading an article and a phrase in there mentioned 2100 expert climate economists. And I just thought that was mind-blowing; there’s such a thing as a climate Economist and there’s 2100 of them. Does that sound right to you? Like what would they do all day?

RM: When I started work in 1996 when I graduated from my PhD, there were only a couple of people who did anything to do with climate change. But like any field there’s a lot of money pumped into climate institutes and into universities to study climate change. So it’s not a standard field in the same sense as trade economics or labor economics or environmental economics would be. So a lot of people will call themselves climate economists now.

So a popular genre now would be impacts analysis. People will take climate model outputs at face value usually the RCP 8.5 scenario, which is garbage but they’ll use it anyway. And then they’ll look at some aspect of the economy, say that pineapple growers are going to experience a five percent reduction in output by 2100 because of climate change.

So there’s that group and among that group, kind of like the hockey stick crowd, where there was sort of an unstated prize for who can get the flattest handle the farthest back. In the climate economics group there’s an unstated prize for who can come up with a highest social cost of carbon. So you can tweak the models and get a social cost of carbon above two hundred dollars, and then above five hundred dollars. Can you get it above 800, and the higher you get, the the more likely your paper is to be into one of the nature journals.

The models that generate social cost of carbon: It’s pretty well known how they operate, and there’s a few knobs on them it’s pretty easy to adjust to get really high social cost of carbon numbers. And it’s also easy to get low social cost of carbon numbers. Then the question becomes, which of these assumptions are more defensible? That’s the part where the question typically doesn’t get asked.

I would guess that a lot of those 2100 climate economists don’t have a big picture approach to the field like they don’t necessarily see climate policy is embedded in the whole array of economic socioeconomic policies, where the ultimate question is what will make people better off on balance all things considered. Because you can get a lot of these young climate economists who will happily endorse Net Zero, even sign letters to the European Parliament encouraging them to pursue Net Zero.

And all they’ve ever studied is what would get us to Net Zero faster and more effectively. But they don’t step back and ask: Is NetZero a very good Target for us to pursue and is the cure worse than the disease? And what would be a climate policy that we could confidently say would be consistent with making people better off around the world over the next 80 years, all things considered?

There aren’t many economists that think about it in that framework. One one of them who does is William D. Nordhaus who won a Nobel Prize in 2018 for his work in climate economics. A lot of the activist crowd were jubilant, thinking finally the economists have noticed climate change. And look at William Nordhaus: He’s an advocate for carbon taxes he won the Nobel Prize. They don’t want to mention the fact that his modeling work showed that: We should do a bit of mitigation to eliminate some of the lowest value activities that generate greenhouse gas emissions, but otherwise the optimal policy is just to live with it and adapt to it. And that’s the upshot of his modeling work and it’s been a very robust result over the 20 or so years that he’s been doing this modeling work. And it convinced the profession enough that his papers are in the best journals and he won a Nobel Prize for it.

Yet as I say the implications are lost on people including a lot of people in this climate economics field that you refer to. Who somehow think the fact that William Nordhaus got the Nobel prize in economics means we should all rush to net zero, even though his own analysis would say absolutely not. That result is not defensible and would make us incomparably worse off and be worse than doing nothing; be worse than just ignoring the climate issue altogether and pursuing economic growth.

TN: I do wonder what percent of the climate economists think that it would be a great thing if we could get back to 280 PPM CO2 and whatever the temperature was in 1850 like end of the little Ice Age with shorter growing seasons etc. Because that seems completely insane to me as an outsider that we would want to spend trillions of dollars to do that, totally crazy yeah.

RM: I doubt even the most enthusiastic climate Economists, meaning the most worried about climate change and most wanting to push a net zero agenda; I think if you really pin them down, very few of them would say, yeah we should try to reverse engineer the 20th century and get back to 280 parts per million, if we could even do it.

Imagine if we could go back in time to 1800 or whatever and and present people with the choice: okay here’s here’s a future path, one where we don’t develop the use of fossil fuels, the economy stays roughly where it is now in terms of living standards, and the atmospheric concentration of CO2 stays at about 280 parts per million and it remains as cold as it is now. We could do that or here’s the other path: We develop fossil fuels, we grow our economies so by 2100 basically everyone around the world is living in a developed economy with a good standard of living and the atmospheric concentration of CO2 goes up to 500 parts per million, and we get a degree and a half or two degrees of warming.

If you presented that choice to people the answer would have been obvious. People would have chosen the path that we chose and halfway along it no one in their right mind would say, oh let’s go back to where we started and and not have all these changes. It’s literally the biggest no-brainer out there.

It was the development of industrial civilization, a net benefit to the world, and the proof is that the places where they didn’t experience that development are doing everything they can to experience it.

And all the supposed harms that people talk about, getting back to extreme weather which we talked about at the beginning: Where are people in the United States moving to? They’re all moving to the extreme weather areas, to the Florida coast and California coast and leaving behind the areas like the Midwest which have the four seasons but not exactly subject to tornadoes and hurricanes. As soon as they can retire they leave those places and go to where they they’ll either have heat waves in the desert or droughts in California or hurricanes on the Florida coast. And that’s where they want to retire to. And then when they get there they can become climate activists and protest greenhouse gases.

Iron Triangle of Public Crises

Postcript:

For more on McKitrick and McIntyre versus the Mann-made Climate hockey stick, see post:

Rise and Fall of the Modern Warming Spike

The first graph appeared in the IPCC 1990 First Assessment Report (FAR) credited to H.H.Lamb, first director of CRU-UEA. The second graph was featured in 2001 IPCC Third Assessment Report (TAR) the famous hockey stick credited to M. Mann.

Reblogged this on Climate Collections.

LikeLike

Prof. McKitrick’s argument is of the “inductive” variety, signifying that the information provided by the runs of the associated climate model is incomplete. I have constructed a “deductive” argument the serves a similar purpose but for which the information provided by runs of the associated model is complete. A copy of this proof is available by request sent to terry_oldberg@yahoo.com.

Cordially,

Terry Oldberg

Engineer/Scientist/Public Policy Researcher

Los Altos Hills, CA USA

1-650-941-0533

terry_oldberg@yahoo.com

LikeLike

‘It’s very hard for people in the climate field to follow those discussions because it’s a it’s econometrics it’s econometric Theory. I teach econometrics at the third year level and so I was just going through stuff I would expect my undergrads maybe the fourth year students to understand. But for a lot of people in the climate field you know this is the first time anyone’s really critiqued the theory behind that method.

It’s the kind of question Steve and I were asked with the Paleo climate stuff: Why are we doing this, why is why wasn’t it people in the field who noticed these flaws in the methods, who dug out the data figured out the method and pointed out the obvious flaws in it. So here I am 20 years after this technique was established I’m publishing a paper that says your fundamental results are invalid; you invoke the theorem incorrectly and your method does not generate unbiased and efficient results like you claimed. In fact it automatically fails the condition so you don’t know anything about what your results are.’ R.M.

Any wonder they don’t wan to reveal the data or show their workings…

LikeLike

Thanks for transcribing this all down. I keep wondering why you vanish for a day or two. It’s no wonder! This card house is going to fall as a result of a thousand small cuts, little by little people will have enough.

Thanks Ron!!!!!

We are the few, the brave and willing to fight hard to bring back some good old common sense to all the activism on climate and the so call end of the world.

LikeLike