On June 14, 2023 Nicola Scafetta published at Science Direct Empirical assessment of the role of the Sun in climate change using balanced multi-proxy solar records. Excerpts in italics with my bolds with exhibits from the study.

By design, climate models exclude solar forcing of earth’s climate,

and perform poorly without it.

Scafetta (2023) Highlights

• The role of the Sun in climate change is hotly debated with diverse models.

• The Earth’s climate is likely influenced by the Sun through a variety of physical mechanisms.

• Balanced multi-proxy solar records were created and their climate effect assessed.

• Factors other than direct TSI forcing account for around 80% of the solar influence on the climate.

• Important solar-climate mechanisms must be investigated before developing reliable GCMs.

Abstract

The role of the Sun in climate change is hotly debated. Some studies suggest its impact is significant, while others suggest it is minimal. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) supports the latter view and suggests that nearly 100% of the observed surface warming from 1850–1900 to 2020 is due to anthropogenic emissions.

However, the IPCC’s conclusions are based solely on computer simulations made with global climate models (GCMs) forced with a total solar irradiance (TSI) record showing a low multi-decadal and secular variability. The same models also assume that the Sun affects the climate system only through radiative forcing – such as TSI – even though the climate could also be affected by other solar processes.

In this paper I propose three “balanced” multi-proxy models of total solar activity (TSA) that consider all main solar proxies proposed in scientific literature. Their optimal signature on global and sea surface temperature records is assessed together with those produced by the anthropogenic and volcanic radiative forcing functions adopted by the CMIP6 GCMs. This is done by using a basic energy balance model calibrated with a differential multi-linear regression methodology, which allows the climate system to respond to the solar input differently than to radiative forcings alone, and to evaluate the climate’s characteristic time-response as well.

The proposed methodology reproduces the results of the CMIP6 GCMs when their original forcing functions are applied under similar physical conditions, indicating that, in such a scenario, the likely range of the equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) could be 1.4 °C to 2.8 °C, with a mean of 2.1 °C (using the HadCRUT5 temperature record), which is compatible with the low-ECS CMIP6 GCM group.

However, if the proposed solar records are used as TSA proxies and the climatic sensitivity to them is allowed to differ from the climatic sensitivity to radiative forcings, a much greater solar impact on climate change is found, along with a significantly reduced radiative effect. In this case, the ECS is found to be 0.9-1.8 °C, with a mean of around 1.3 °C. Lower ECS ranges (up to 20%) are found using HadSST4, HadCRUT4, and HadSST3.

The result also suggests that about 80% of the solar influence on the climate may not be induced by TSI forcing alone, but rather by other Sun-climate processes (e.g., by a solar magnetic modulation of cosmic ray and other particle fluxes, and/or others), which must be thoroughly investigated and physically understood before trustworthy GCMs can be created. This result explains why empirical studies often found that the solar contribution to climate changes throughout the Holocene has been significant, whereas GCM-based studies, which only adopt radiative forcings, suggest that the Sun plays a relatively modest role. The appendix includes the proposed TSA records.

Comparative Analysis

Figure 5. (A) Anthropogenic (blue) and volcanic (orange) effective radiative forcing functions adopted by the CMIP6 GCMs (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). (B) Comparison between the solar effective radiative forcing function from Table Annex III of the IPCC-AR6 (green) (after Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021) and the three TSI forcing functions deduced from the TSI records shown in Fig. 4. All records are anomalies relative to their values in 1850.

The solar forcing functions depicted in Fig. 5B differ in several respects. Just a very modest secular trend can be seen for the solar forcing function used by the CMIP6 GCMs, which has remained nearly constant for about 200 years. Although not depicted in Fig. 5B, the TSI forcing adopted by the CMIP6 GCMs is so flat that even the 1790–1830 Dalton grand solar minimum almost coincides with the 1890–1910 solar minimum and the 2019 solar cycle minimum (Supplementary Data Table S5). Furthermore, because this record is also based on SATIRE and the PMOD TSI satellite composite, its solar effective forcing function decreased progressively from 1970 to 2020. Thus, by using this TSI record, the CMIP6 GCMs could only conclude that solar forcing did not account for almost any of the warming observed after the pre-industrial period (1850–1900), and, particularly, from 1980 to 2020. (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021).

On the contrary, the other three TSI records reveal a multidecadal oscillation as well as a clear increasing secular trend from the Dalton solar minimum to 2000. More specifically, the TSI forcing significantly increased from the Dalton minimum (1810–1815) to around 1870–1876, then declined until around 1890–1905; it increased rapidly between 1910 and the 1940s, and declined again between 1950 and 1975. The TSI forcing then increased again until 2000, when it began to gradually fall until 2022. This oscillating pattern is especially noteworthy because, as demonstrated below, it is closely correlated with the changes observed in total surface temperature records, which show a very similar increasing trend and multi-decadal modulation (cf.: Scafetta et al., 2004, Scafetta and West, 2006, Scafetta and West, 2008, Scafetta, 2009, Scafetta, 2010, Scafetta, 2012b, Scafetta, 2013a, Scafetta, 2021b).

Figure 8. (A) HadCRUT5 global surface temperature versus the CMIP6 GCM ensemble average; (A’) the two records are detrended with the function f(t) = a (x-1850)2. (B) HadCRUT5 global surface temperature versus the energy balance model (Eq. (16)) using the TSI proxy model #2; (B’) the same as above. The green curves in Fig. 8A and B are sketches that highlight the different multi-decadal modulation of the red curves in Fig. 8A (monotonically increasing, like the anthropogenic forcing function) and in Fig. 8B (oscillating, like the temperature records).

Fig. 8 compares the HadCRUT5 global surface temperature record to (A) the CMIP6 GCM ensemble mean record and (B) the energy balance model (Eq. (16)) using the proposed TSI proxy model #2, which does not use the GCMs’ low secular-variability TSI record. The GCM simulation depicted in Fig.8A monotonically warms up, although occasional volcanic eruptions momentarily cause cold spikes; the monotonic warming trend produced by the model is simulated by the green curve. On the contrary, the model provided in Fig. 8B indicates an oscillating pattern developing around a warming trend. The global surface temperature record shows a similar growing trend, regulated by an approximately 60-year oscillation: the period 1880–1910 experienced a global cooling; the period 1910–1940 was characterized by considerable warming; and the period 1940–1970 experienced another global cooling. From 1880 to 1970, the model in Fig. 8B reproduces this oscillating pattern more precisely (corr. coeff. r = 0.79) than the CMIP6 GCM ensemble average simulation depicted in Fig. 8A (corr. coeff. r = 0.74). Thus, Fig. 8 illustrates that the suggested model (red curve, Fig. 8B) exhibits a multidecadal modulation that correlates significantly better with the temperature record (blue curve) than the GCM ensemble average simulation (red curve, Fig. 8A).

The different performance of the CMIP6 GCM ensemble average simulation and of the proposed regression model in reproducing the temperature pattern from 1850 to 1950 becomes more evident if a quadratic upward trend is detrended from the records. The correlation coefficient is r = 0.45 using the GCM ensemble average simulation (Fig. 8A’), and r = 0.55 using the proposed regression model (Fig. 8B’).

This result suggests that the observed multi-decadal modulation of the

temperature records could have been mostly determined by solar forcings,

and not by chaotic internal oscillations of the climate system.

Conclusion

The IPCC (Solomon and et al., 2007; Stocker and et al., 2014; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021) conclusion that the Sun’s role in climate change has been negligible since the pre-industrial period (1850–1900) derives from the fact that this organization only consider the solar climatic signature produced by the present-day GCMs. These models, however, are computer programs that can only employ equations describing physical mechanisms that are already well known. Anything unknown or ambiguous cannot be included in the GCM software. If the climatic influence of neglected physical processes is significant, the reductionist approach employed in the GCMs for assessing climate change attributions may be completely inappropriate for the task.

The CMIP6 GCMs appear to greatly underestimate the Sun’s role in climate change because of two major limitations:

(i) erroneous solar forcings have likely been integrated into the models; and

(ii) TSI alone appears to likely be not the most important solar forcing.

Additional solar-magnetism related forcings and associated mechanisms are not included in the GCMs because they are currently poorly understood, despite the fact that there are several empirical indications that they might sufficiently modulate the cloud cover system (by 5% or less) to explain a significant component of the observed climatic changes (Svensmark and Friis-Christensen, 1997, Shaviv, 2002, Svensmark et al., 2016, Easterbrook, 2019, Svensmark, 2022; ). In fact, Table 1 shows that the actual climate sensitivity to TSA variations, which is expressed by kS, can be 4-7 times greater than the climate sensitivity to radiative forcing alone, which was denoted by kA.

Thus, about 80% of the solar influence on the climate could be generated

by processes other than direct TSI forcing. If this result is correct,

several solar-climate mechanisms must be thoroughly investigated

and fully understood before reliable GCMs can be developed.

The Sun Rules, and Warming from CO2 is Impossible

A complement to Scafetta’s study is a Quadrant article by Mark Imisides explaining the geophysical realities ruling out global warming from CO2. DIY ocean heating (Hint: It’s the water, isn’t it?) Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Scarcely a day goes by without us being warned of coastal inundation by rising seas due to global warming.

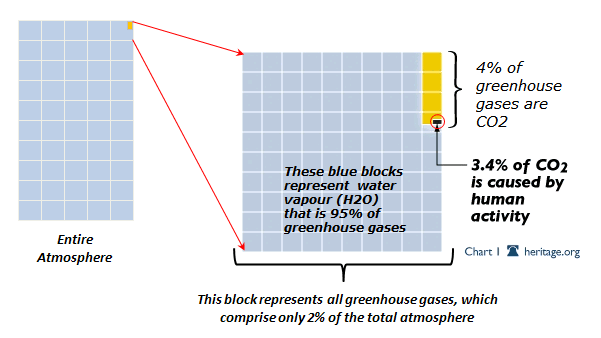

Carbon dioxide, we are told, traps heat that has been irradiated by the oceans,

and this warms the oceans and melts the polar ice caps.

While this seems a plausible proposition at first glance, when one actually examines it closely a major flaw emerges. In a nutshell, water takes a lot of energy to heat up, and air doesn’t contain much. In fact, on a volume/volume basis, the ratio of heat capacities is about 3300 to 1.

This means that to heat 1 litre of water by 1˚C it would take 3300 litres of air

that was 2˚C hotter, or 1 litre of air that was about 3300˚C hotter!

This shouldn’t surprise anyone. If you ran a cold bath and then tried to heat it by putting a dozen heaters in the room, does anyone believe that the water would ever get hot?

The problem gets even stickier when you consider the size of the ocean.

Basically, there is too much water and not enough air.

The ocean contains a colossal 1,500,000,000,000,000,000,000 litres of water! To heat it, even by a small amount, takes a staggering amount of energy. To heat it by a mere 1˚C, for example, an astonishing 6,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 joules of energy are required.

Let’s put this amount of energy in perspective. If we all turned off all our appliances and went and lived in caves, and then devoted every coal, nuclear, gas, hydro, wind and solar power plant to just heating the ocean, it would take a breathtaking 32,000 years to heat the ocean by just this 1˚C!

In short, our influence on our climate, even if we really tried, is miniscule!

So it makes sense to ask the question – if the ocean were to be heated by greenhouse warming of the atmosphere, how hot would the air have to get? If the entire ocean is heated by 1˚C, how much would the air have to be heated by to contain enough heat to do the job?

Well, unfortunately for every ton of water there is only a kilogram of air. Taking into account the relative heat capacities and absolute masses, we arrive at the astonishing figure of 4,000˚C.

That is, if we wanted to heat the entire ocean by 1˚C,

and wanted to do it by heating the air above it,

we’d have to heat the air to about 4,000˚C hotter than the water.

And another problem is that air sits on top of water – how would hot air heat deep into the ocean? Even if the surface warmed, the warm water would just sit on top of the cold water.

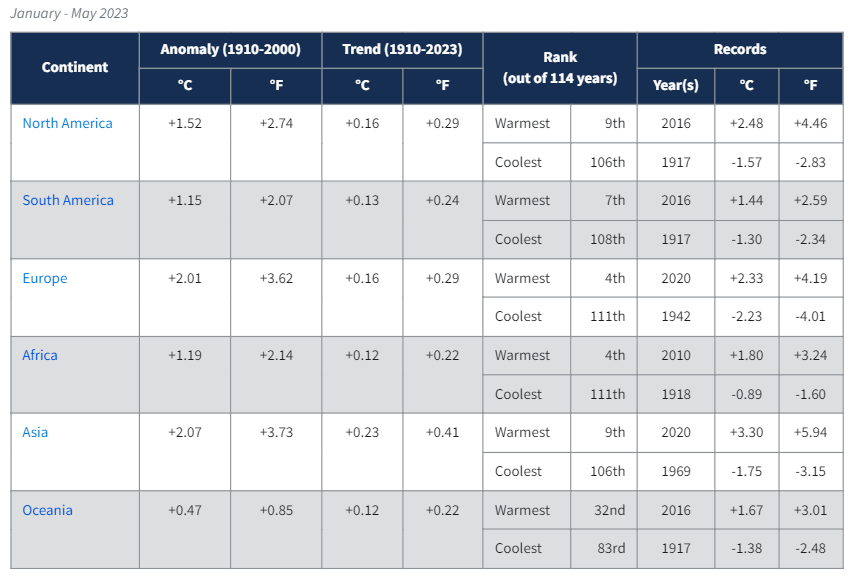

Thus, if the ocean were being heated by greenhouse heating of the air, we would see a system with enormous thermal lag – for the ocean to be only slightly warmer, the land would have to be substantially warmer, and the air much, much warmer (to create the temperature gradient that would facilitate the transfer of heat from the air to the water).

Therefore any measurable warmth in the ocean would be accompanied by a huge and obvious anomaly in the air temperatures, and we would not have to bother looking at ocean temperatures at all.

So if the air doesn’t contain enough energy to heat

the oceans or melt the ice caps, what does?

The earth is tilted on its axis, and this gives us our seasons. When the southern hemisphere is tilted towards the sun, we have more direct sunlight and more of it (longer days). When it is tilted away from the sun, we have less direct sunlight and less of it (shorter days).

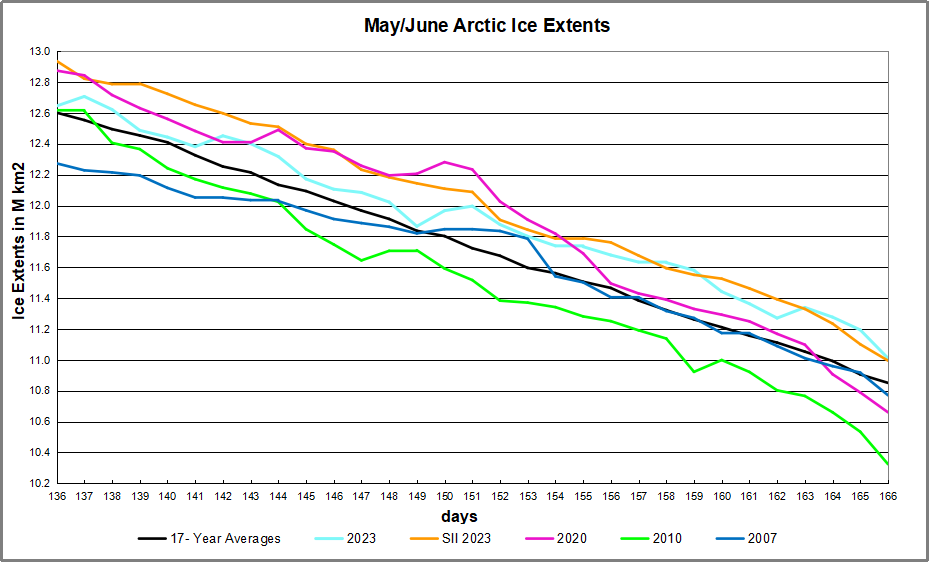

The direct result of this is that in summer it is hot and in winter it is cold. In winter we run the heaters in our cars, and in summer the air conditioners. In winter the polar caps freeze over and in summer 60-70% of them melt (about ten million square kilometres). In summer the water is warmer and winter it is cooler (ask any surfer).

All of these changes are directly determined

by the amount of sunlight that we get.

When the clouds clear and bathe us in sunlight, we don’t take off our jumper because of greenhouse heating of the atmosphere, but because of the direct heat caused by the sunlight on our body. The sun’s influence is direct, obvious, and instantaneous.

If the enormous influence of the sun on our climate is so obvious, then, by what act of madness do we look at a variation of a fraction of a percent in any of these variables, and not look to the sun as the cause?

Why on earth (pun intended) do we attribute any heating of the oceans to carbon dioxide, when there is a far more obvious culprit, and when such a straightforward examination of the thermodynamics render it impossible.

Increasingly students, journalists and other writers are using AI bots to do research on their subjects. The danger concerns the bias built into the software. Harvey Risch demonstrates how you can get a slanted, unbalanced perspective, and also how to interrogate an AI bot to reveal its programmed narrative. His Brownstone article is

Increasingly students, journalists and other writers are using AI bots to do research on their subjects. The danger concerns the bias built into the software. Harvey Risch demonstrates how you can get a slanted, unbalanced perspective, and also how to interrogate an AI bot to reveal its programmed narrative. His Brownstone article is