Why climate-finance ‘flows’ are falling short of $100bn pledge is an informative article from CarbonBrief. Excerpts below in italics followed by a comment from Bjorn Lomborg.

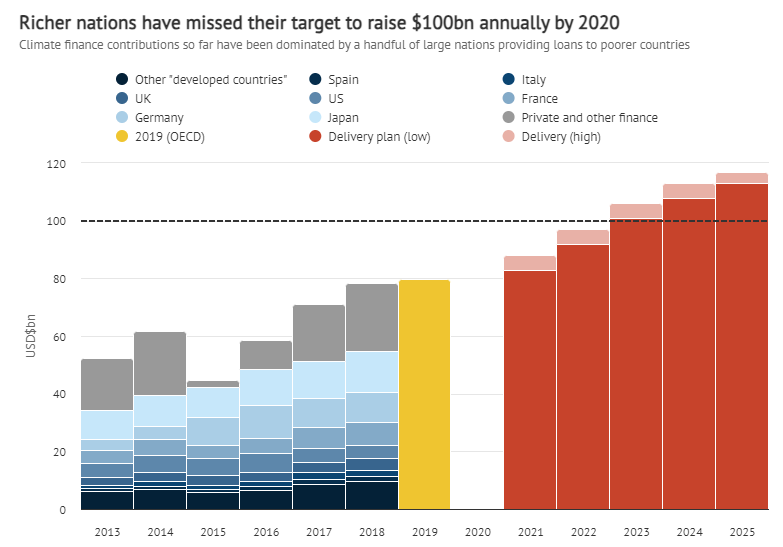

One of the biggest and most contentious issues in climate politics is the provision of money to help poorer countries cut emissions and protect themselves from climate impacts. In 2009, wealthy nations pledged to “mobilise” $100bn in “climate finance” annually by 2020 to help vulnerable nations deal with climate change. As the title notes, even now the target has not been met.

Politicians and observers have warned that this failure could undermine trust between nations as they head into negotiations in Dubai. What is more, there are widespread concerns about the quality of finance being offered, with questions surrounding the use of loans instead of grants, different definitions of “climate finance” and insufficient funding for adaptation efforts.

In this article, which updates and builds on a previous analysis published in 2018, Carbon Brief assesses the state of international climate finance as nations prepare for the next COP. It uses the latest numbers collated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a club of mostly wealthy nations, many of which are responsible for contributing climate finance.

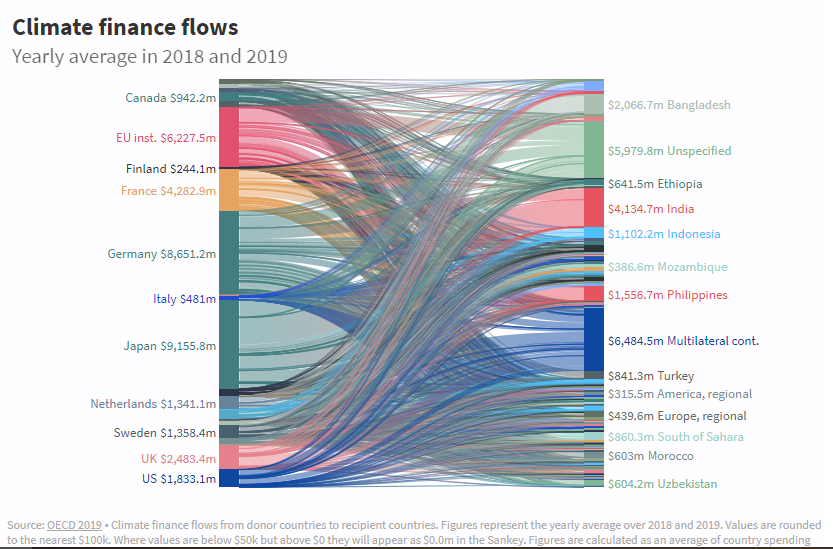

The OECD, a Paris-based intergovernmental economic organisation, asks its 36 member countries to report on their foreign aid, including climate finance. The data captures climate finance that is both bilateral (country to country) and multilateral (via international institutions) It also gives detailed information about funded projects. (The OECD calls this database “climate-related development finance” rather than strictly climate finance).

Key takeaways from 2015-2016 Report

- Donor governments gave climate finance totalling $34bn in 2015 and $37bn in 2016, according to OECD estimates (note that this is not a full estimate of money counting towards the $100bn pledge – see below for more).

- Japan was the largest donor, giving $10.3bn per year (bn/yr) on average over the two years. It was followed, in order, by Germany, France, the UK and the US.

- India was the largest recipient on average, receiving $2.6bn/yr. It was followed, in order, by Bangladesh, Vietnam, the Philippines and Thailand

- The single largest “country-to-country” flow was an average yearly $1.6bn from Japan to India.

- The US was the top contributor to the multilateral Green Climate Fund (GCF) in 2016. (However, the US has now ended its support for the GCF).

- Around $16bn/yr went to mitigation-only projects, compared to $9bn for adaptation-only projects.

Around 42% of the finance consisted of “debt instruments”, such as loans.

Key takeaways from 2018-2019 Report

- In 2019, the OECD found that climate finance had reached $79.6bn, up just 2% from 2018, and while official figures for 2020 are not yet available, Bloomberg reported that rich countries reckon they had raised $88-90bn, as of October 2021.

- The shares attributed to countries are based on analysis by the World Resources Institute (WRI) of bilateral and multilateral development funds that can be traced to Annex II nations. These roughly align with the OECD’s figures, which are not broken down by country but, like the WRI’s, are partly derived from Annex II nations’ reports to the UNFCCC.

- The remaining finance, indicated by the grey bars in the chart above, is made up of export credits, additional outflows from multilateral institutions and, most of all, private contributions by businesses and philanthropic groups (this is an approximation based on the OECD’s total values with the WRI estimates removed).

- Private funds count towards the $100bn target, but the WRI did not include them in its analysis as the data is less complete and difficult to attribute to individual nations. The OECD estimates that annual private finance has been stable at around $14bn since 2017.

- The top five finance providers – Japan, Germany, France, the UK and the US – have remained the same since Carbon Brief’s last analysis for 2015/16. These five nations contributed more than 60% of the 2018/19 finance. While Japan, Germany and France appear to be by far the biggest contributors, the WRI warns that the lack of clarity around climate finance reporting means the numbers should be approached with caution.

- As in Carbon Brief’s previous analysis, India was by far the biggest recipient of climate finance, with more than double the funds received by the next largest, Bangladesh. Japan and Germany provided about 94% of the funds to India, almost all in the form of loans.

Implications

Climate finance figures are widely contested, with many global-south nations questioning how much funding is new and not simply diverted from other development funds. Criticism has also been levelled at the overreliance on loans and the inclusion of support for “high-efficiency” coal plants by Japan and Australia.

A recent assessment prepared by the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance concluded that developing countries require $5.8-5.9tn up to 2030 in order to fund less than half of the actions outlined in their official climate plans – although some of this would be funded domestically.

This year’s negotiations are likely to spark calls for a significant scaling up of finance, although the slow pace of proceedings means that, for the time being, the focus of new goal discussions will primarily be on agreeing a framework for future talks.

Nevertheless, there are various issues that could be on the table during this next phase, including ensuring that more money is spent on adaptation.

The Paris Agreement specifies that climate finance should aim for an even split between these two categories, but funding has long been skewed towards mitigation. According to Jan Kowalzig, a senior policy adviser at Oxfam, governments often tend to view such projects as more attractive investments:

“Since [mitigation projects] often have to do with energy, they seem to be more directly linked to a country‘s development, even though, of course, this is a huge misconception given the central (but, for politicians, often less visible) role of adaptation.”

Of the roughly $40bn average for the 2018/19 period, 39% of money went on mitigation, while just 25% went on adaptation – a slightly more even split than was recorded in Carbon Brief’s previous analysis for 2015/16.

However, other estimates, including the OECD’s own climate finance report, suggest a more pronounced split, with around three times as much finance going to mitigation than adaptation in 2018 and 2019.

This imbalance is a major concern amid rapidly escalating climate costs. The UN Environment Programme places current annual adaptation costs for “developing countries” at $70bn, but says they will reach $140-300bn by 2030.

Ensuring adequate adaptation finance in the coming years is, therefore, seen by many vulnerable nations as a key priority for post-2025 climate finance plans as they are developed.

Climate Money Could Be Better Spent

Bjorn Lomborg When it comes to climate change, let’s get our priorities straight

We must also bear in mind that global warming is not the planet’s only challenge. We often hear that it is the defining issue of our time, but it is no such thing. By the 2070s, the IPCC — the U.N. climate change panel — estimates that warming will cost between 0.2 and 2 percent of global GDP. This is certainly a problem, but not the end of world.

Speaking of climate change in catastrophic terms easily makes us ignore bigger problems, including malnutrition, tuberculosis, malaria and corruption. The World Health Organization estimates that climate change since the 1970s causes about 140,000 additional deaths each year, and toward the middle of the century will kill 250,000 people annually, mostly in poor countries. This pales in comparison with much deadlier environmental problems such as indoor air pollution, claiming 4.3 million lives annually, outdoor air pollution killing 3.7 million and lack of water and sanitation killing 760,000. Outside of environment, the problems are even bigger: Poverty arguably kills 18 million each year.

Every dollar spent on climate change could instead help save many more people from these more tractable problems. The current approach to subsidize solar and wind arguably saves one life across the century for every $4 million spent — the same expenditure on vaccinations could save 4,000 lives. Each person — and the next president — needs to decide his or her legacy.

Postscript: Financing for Climate Aid is a Fraction of the Full Cost of Climate Crisis Inc.

A fuller accounting of the climate crisis industry more likely exceeds 2,000,000,000,000 US$ per year (2 Trillion)

See Climate Crisis Inc. Update

2 comments