The big news this week is the breakdown of Climate “Loss and Damge” talks in preparation for the Dubai COP to start end of November. The news report is repeated widely with the same headline and content. Example from Jakarta Post, Oct. 21, 2023: Climate ‘loss and damage’ talks end in failure

A crucial meeting on climate “loss and damages” ahead of COP28 ended in failure Saturday, with countries from the global north and south unable to reach an agreement, according to sources involved in the talks. The agreement to set up a dedicated fund to help vulnerable countries cope with climate “loss and damage” was a flagship achievement of last year’s COP27 talks in Egypt.

But countries left the details to be worked out later. A series of talks held this year have tried to tease out consensus on fundamentals like the structure, beneficiaries and contributors — a key issue for richer nations who want China to pay into the fund.

The failure “is a clear indication of the deep chasm between rich and poor nations”, Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy for Climate Action Network International, said in a statement to AFP on Saturday. “Developed countries must be held accountable for their shameless attempts to push the World Bank as the host of the fund, their refusal to discuss the necessary scale of finance, and their blatant disregard for their responsibilities” under the terms of already established international climate agreements, he said.

More in depth reporting comes from Climate Home News article World Bank controversy sends loss and damage talks into overtime.

At Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, governments tasked the committee with working out what a new loss and damage fund for climate victims should look like and present their proposals to Cop28 in November.

The fund is supposed to channel money to people who have suffered

loss and damage caused by climate change. This could mean rebuilding homes

after a hurricane or supporting farmers displaced by recurrent drought.

Failure to reach consensus risks delaying support to those in need.

But developing countries were incensed by a proposal to host the fund at the World Bank, painting it as a US power grab. And rich-poor divides persisted on how to define the “vulnerable” groups eligible for funds and who gets to control spending.

Pedro Luis Pedroso Cuesta is a Cuban diplomat and chair of the G77+China bloc, which represents all the developing countries.

Speaking from Aswan, he told reporters on Thursday: “At this late hour, a small group of nations responsible for the most significant proportion of the stock of greenhouse gases have tried to bargain potential support for a Fund on one side with eligibility and administrative arrangements.”

Developing nations have argued that the World bank is too slow, inefficient,

unaccountable and lacks the organisational culture to tackle climate change.

He said that consultations with the Washington-DC based bank had “displayed clearly” that it was “not fit for purpose in relation to what we’re looking for” and the fund should be set up as part of the United Nations instead.

Who benefits?

The second main division is over which countries are prioritised for funding. Developed countries want the funds to be allocated “based on vulnerability”.

There is no clear definition of vulnerability and Cuesta said this criteria would impede the fund’s ability to respond to recent climate-related floods in middle-income countries like Pakistan and Libya.

Developing countries fear that in practice “vulnerability” criteria mean funds will be restricted to just the world’s least developed countries (LDCs) and small islands developing states (Sids).

The 46 LDCS are mostly in Africa and parts of Asia. Major nations like

China, India, Brazil, Nigeria and South Africa are neither LDCs or Sids.

Further splits include developing nations wanting a target of $100 billion of funding a year by 2030 to be included and developed countries wanting to earmark budgets for slow onset events, recovery and reconstruction and small countries.

Negotiators have almost agreed one thorny issue though. The US had pushed for the fund’s board to include seats for nations that paid into the fund, sparking accusations that they were trying to rig the board in rich nations’ favour.

Friday morning’s draft said there would be 12 board members from developed countries and 14 from developing ones. There could also be non-voting members representing indigenous peoples and climate-induced migrants, although negotiators have yet to agree that.

Climate Loss and Damage is a Legal and Moral House of Cards

Mike Hulme explained the house of cards underlying the claims for compensation from extreme weather loss and damage. He addressed this directly in his 2016 article Can (and Should) “Loss and Damage” be Attributed to Climate Change?. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

One of the outcomes of the eighteenth negotiating session of the Conference of the Parties (COP18) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, held in Doha last December, was the agreement to establish institutional arrangements to “address loss and damage associated with the impacts of climate change.” This opens up new possibilities for allocating international climate adaptation finance to developing countries. A meeting this week in Bonn (25–27 February), co-organized by the UN University Institute for Environmental and Human Security and the Loss and Damage in Vulnerable Countries Initiative, is bringing together various scholars and policymakers to consider how this decision might be implemented, possibly by as early as 2015.

At the heart of the loss and damage (L&D) agenda is the idea of attribution—that specific losses and damages in developing countries can be “associated with the impacts of climate change,” where “climate change” means human-caused alterations to climate. It is therefore not just any L&D that qualify for financial assistance under the Convention; it is L&D attributable to or “associated with” a very specific causal pathway.

Developing countries face some serious difficulties—at best, ambiguities—

with this approach to directing climate adaptation finance.

This is particularly so given the argument that the new science of weather attribution opens the possibility for a framework of legal liability for L&D, which has recently gained prominence (see here and here). Weather attribution science seeks to generate model-based estimates of the likelihood that human influence on the climate caused specific weather extremes.

Weather attribution should not, however, be used to make the funding of climate adaptation in developing countries dependent on proving liability for weather extremes.

There are four specific problems with using the post-Doha negotiations on L&D to advance the legal liability paradigm for climate adaptation. First, with what level of confidence can it be shown that specific weather or climate hazards in particular places are caused by anthropogenic climate change, as opposed to a naturally varying climate? Weather attribution scientists claim that such knowledge is achievable, but this knowledge will be partial, probabilistic, and open to contestation in the courts.

Second, even if such scientific claims were defendable, how will we define “anthropogenic?” Weather attribution science—if it is to be used to support a legal liability paradigm—needs to be capable of distinguishing between the meteorological effects of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and those from land use change, and between the effects of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, black carbon (soot), and aerosol emissions. Each of these sources and types of climate-altering agents implicates different social and political actors and interests, so to establish liability in the courts, any given weather or climate hazard would need to be broken down into a profile of multiple fractional attributions. This adds a further layer of complexity and contestation to the approach.

Third, L&D may often be as much—or more—a function of levels of social and infrastructural development as it is a function of weather or climate hazard. Whether or not an atmospheric hazard is (partially) attributable to a liable human actor or institution is hardly the determining factor on the extent of the L&D. A legal liability framework based on attribution science promotes a “pollutionist approach” to climate adaptation and human welfare rather than a “developmentalist approach.” Under a pollutionist approach, adaptation is primarily about avoiding the dangers of human-induced climate change rather than building human resilience to a range of weather risks irrespective of cause. This approach has very specific political ramifications, serving some interests rather than others (e.g., technocratic and centralized control of adaptation funding over values-centered and decentralized control).

Finally, if such a legal framework were to be adopted, then what account should be taken of “gains and benefits” that might accrue to developing countries as a result of the impacts of climate change? Not all changes in weather and climate hazard as a result of human influence are detrimental to human welfare, and the principle of symmetry would demand that a full cost-benefit analysis lie at the heart of such a legal framework. This introduces another tier of complexity and contestation.

Following Doha and the COP18, the loss and damage agenda now has institutional force, and the coming months and years will see rounds of technical and political negotiation about how it may be put into operation. This agenda, however, should not place climate adaptation funding into the framework of legal liability backed by the new science of weather attribution.

Hulme goes more deeply into the Loss and Damage difficulties in his 2014 paper Attributing Weather Extremes to ‘Climate Change’: a Review. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

In this third and final review I survey the nascent science of extreme weather event attribution. The article proceeds by examining the field in four stages: motivations for extreme weather attribution, methods of attribution, some example case studies and the politics of weather event Attribution.

Hulme concludes by discussing the political hunger for scientific proof in support of policy actions.

But Hulme et al. (2011) show why such ambitious claims are unlikely to be realised. Investment in climate adaptation, they claim, is most needed “… where vulnerability to meteorological hazard is high, not where meteorological hazards are most attributable to human influence” (p.765). Extreme weather attribution says nothing about how damages are attributable to meteorological hazard as opposed to exposure to risk; it says nothing about the complex political, social and economic structures which mediate physical hazards.

And separating weather into two categories — ‘human-caused’ weather

and ‘tough-luck’ weather – raises practical and ethical concerns about

any subsequent investment allocation guidelines which excluded

the victims of ‘tough-luck weather’ from benefiting from adaptation funds.

Synopsis of this paper is at X-Weathermen are Back!

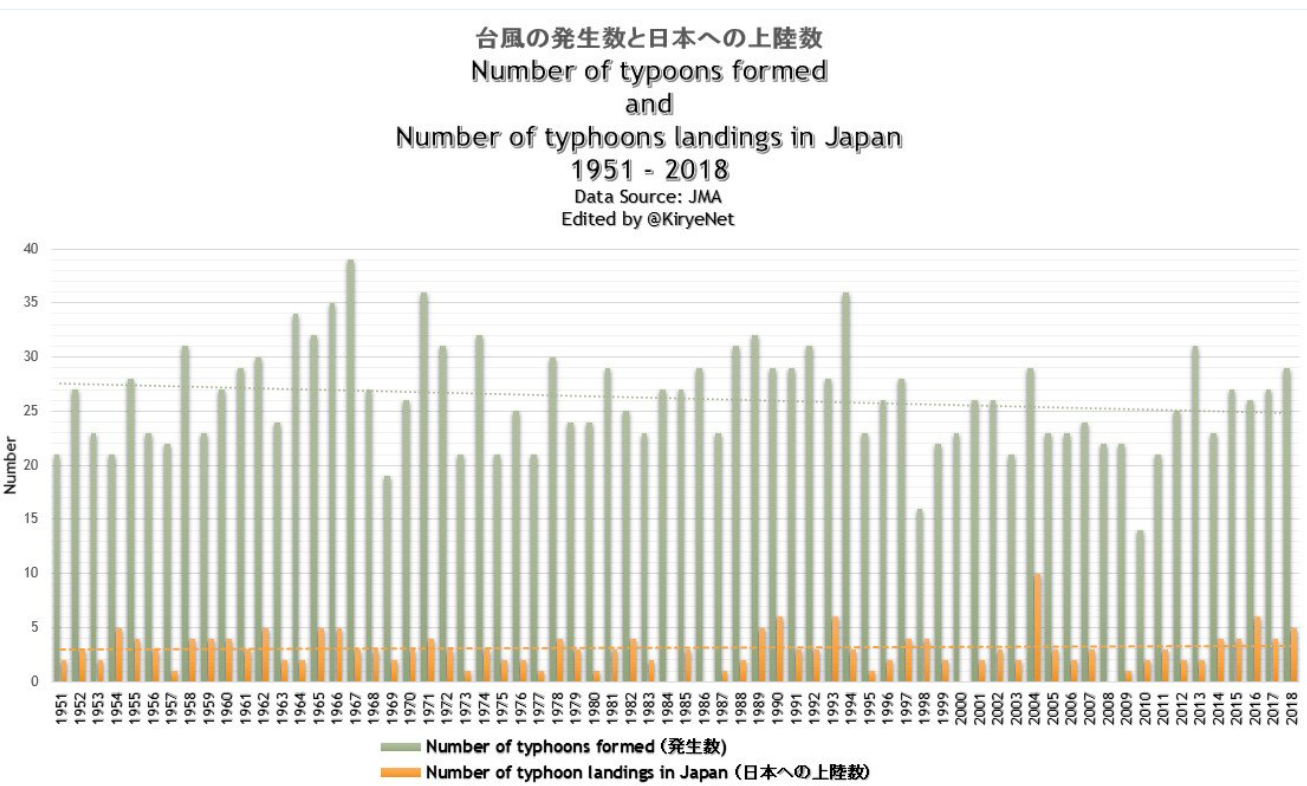

Integrated Storm Activity Annually over the Continental U.S. (ISAAC)

See also Data vs. Models #3: Disasters

4 comments