Latest INM Climate Model Projections Triggered by Scenario Inputs

The latest climate simulation from the Russian INM was published in April 2024: Simulation of climate changes in Northern Eurasia by two versions of the INM RAS Earth system model. The paper includes discussing how results are driven greatly by processing of cloud factors. But first for context readers should be also aware of influences from scenario premises serving as model input, in this case SSP3-7.0.

Background on CIMP Scenario SSP3-7.0

A recent paper reveals peculiarities with this scenario. Recognizing distinctiveness of SSP3-7.0 for use in impact assessments by Shiogama et al (2024). Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

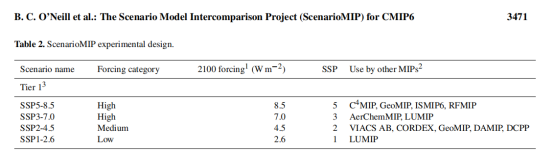

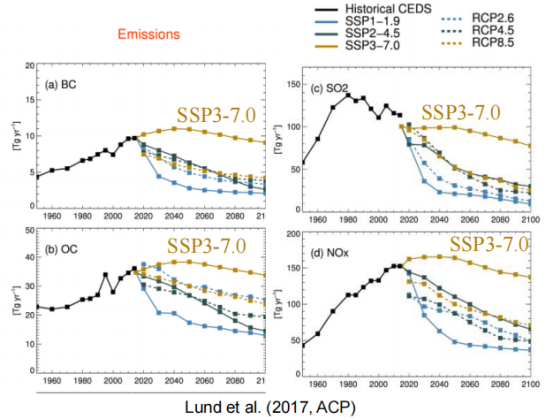

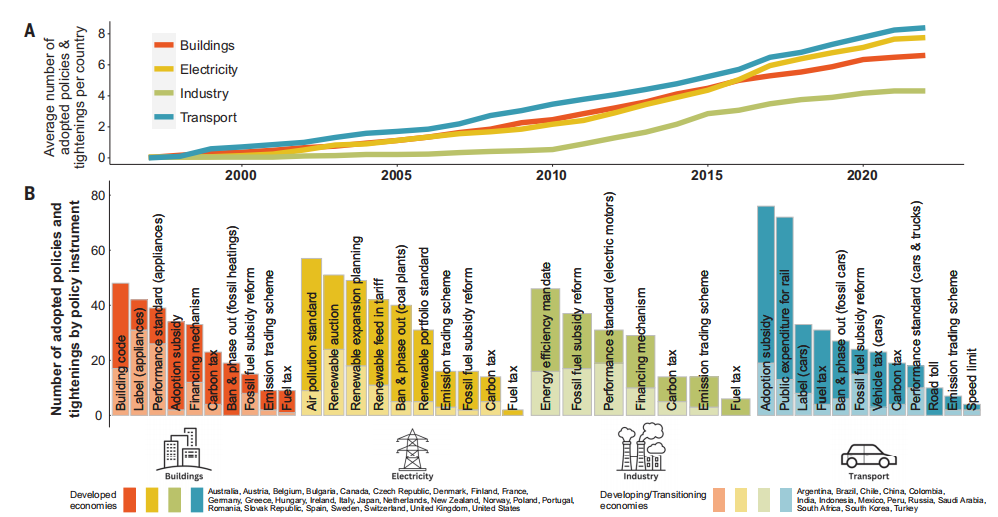

Because recent mitigation efforts have made the upper-end scenario of the future GHG concentration (SSP5-8.5) highly unlikely, SSP3-7.0 has received attention as an alternative high-end scenario for impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability (IAV) studies. However, the ‘distinctiveness’ of SSP3-7.0 may not be well-recognized by the IAV community. When the integrated assessment model (IAM) community developed the SSP-RCPs, they did not anticipate the limelight on SSP3-7.0 for IAV studies because SSP3-7.0 was the ‘distinctive’ scenario regarding to aerosol emissions (and land-use land cover changes). Aerosol emissions increase or change little in SSP3-7.0 due to the assumption of a lenient air quality policy, while they decrease in the other SSP-RCPs of CMIP6 and all the RCPs of CMIP5. This distinctive high-aerosol-emission design of SSP3-7.0 was intended to enable climate model (CM) researchers to investigate influences of extreme aerosol emissions on climate.

SSP3-7.0 Prescribes High Radiative Forcing

SSP3-7.0 Presumes High Aerosol Emissions

• Aerosol emissions increase or change little in SSP3-7.0 due to the assumption of a lenient air quality policy, while they decrease in the other SSP-RCPs of CMIP6 and all the RCPs of CMIP5.

• This distinctive high-aerosol-emission design of SSP3- 7.0 was intended to enable AerChemMIP to investigate the consequences of continued high levels of aerosol emissions on climate.

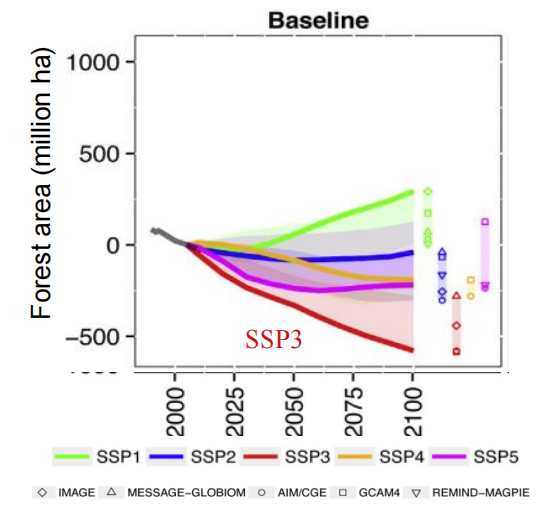

SSP3-7.0 Supposes Forestry Deprivation

• Decreases in forest area were also substantial in SSP3- 7.0, unlike in the other SSP-RCPs.

• This design enables LUMIP to analyse the climate influences of extreme land-use and land-cover changes.

SSP3-7.0 Projects High Population Growth in Poorer Nations

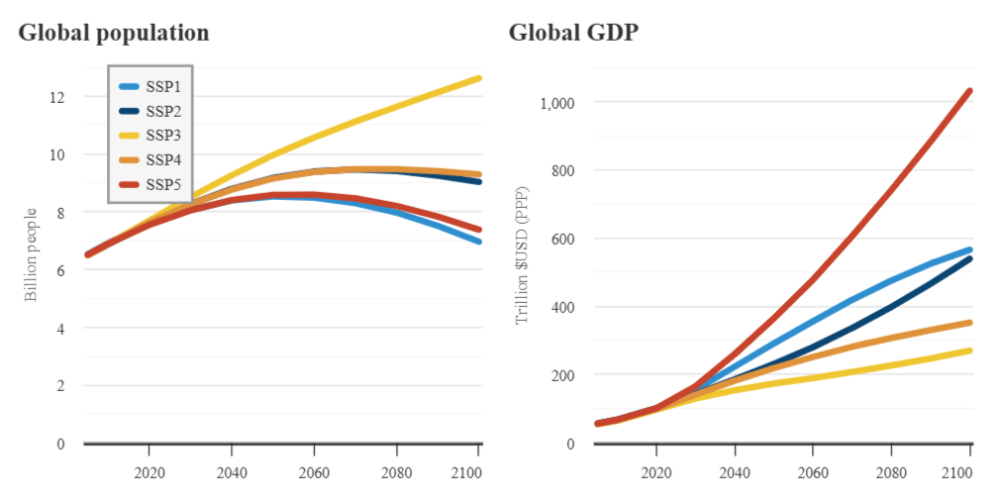

Global population (left) in billions and global gross domestic product (right) in trillion US dollars on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis. Data from the SSP database; chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

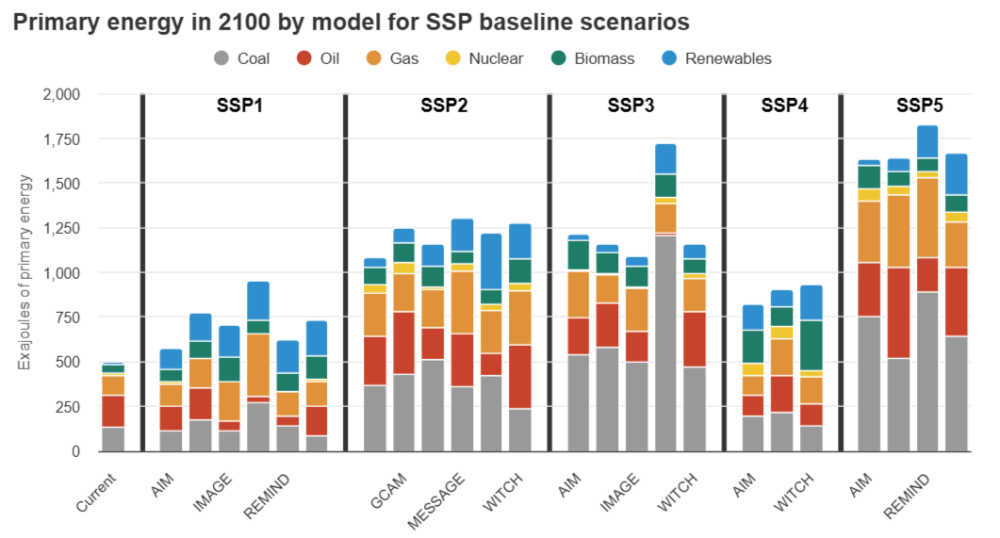

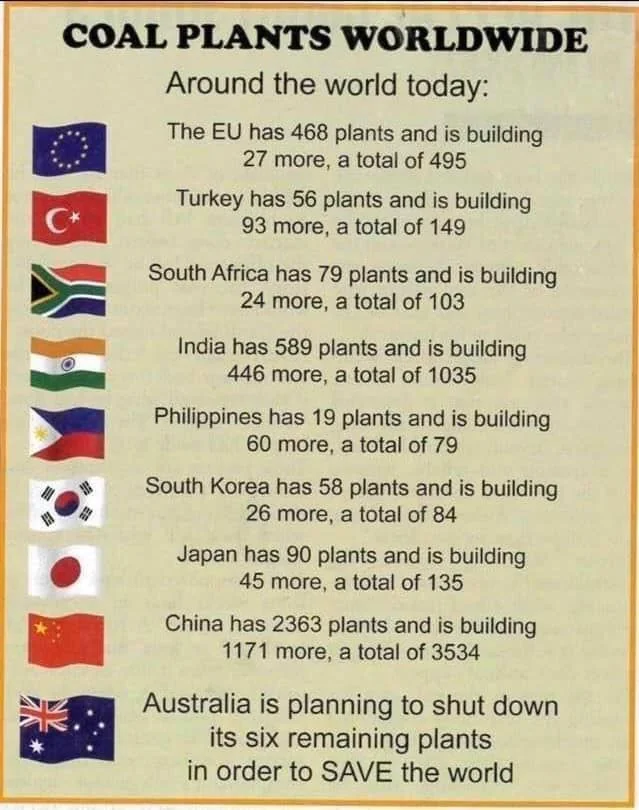

SSP3-7.0 Projects Growing Use of Coal Replacing Gas and Some Nuclear

My Summary: Using this scenario presumes high CO2 Forcing (Wm2), high aerosol emissions and diminished forest area, as well as much greater population and coal consumption. Despite claims to the contrary, this is not a “middle of the road” scenario, and a strange choice for simulating future climate metrics due to wildly improbable assumptions.

How Two Versions of a Reasonable INM Climate Model Respond to SSP3-7.0

The preceding information regarding the input scenario provides a context for understanding the output projections from INMCM5 and INMCM6. Simulation of climate changes in Northern Eurasia by two versions of the INM RAS Earth system model. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

Introduction

The aim of this paper is the evaluation of climate changes during last several decades in the Northern Eurasia, densely populated region with the unprecedentedly rapid climate changes, using the INM RAS climate models. The novelty of this work lies in the comparison of model climate changes based on two versions of the same model INMCM5 and INMCM6, which differ in climate sensitivities ECS and TCR, with data from available observations and reanalyses. By excluding other factors that influence climate reproduction, such as different cores of GCM components, major discrepancies in description of physical process or numerical schemes, the assessment of ECS and TCR role in climate reproduction can be the exclusive focus. Also future climate projections for the middle and the end of 21st century in both model versions are given and compared.

After modification of physical parameterisations, in the model version INMCM6 ECS increased from 1.8K to 3.7K (Volodin, 2023), and TCR increased from 1.3K to 2.2K. Simulation of present-day climate by INMCM6 Earth system model is discussed in Volodin (2023). A notable increase in ECS and TCR is likely to cause a discrepancy in the simulation of climate changes during last decades and the simulation of future climate projections for the middle and the end of 21st century made by INMCM5 and INMCM6.

About 20% of the Earth’s land surface and 60% of the terrestrial land cover north of 40N refer to Northern Eurasia (Groisman et al, 2009). The Hoegh-Guldberg et al (2018) states that the topography and climate of the Eurasian region are varied, encompassing a sharply continental climate with distinct summer and winter seasons, the northern, frigid Arctic environment and the alpine climate on Scandinavia’s west coast. The Atlantic Ocean and the jet stream affect the climate of western Eurasia, whilst the Mediterranean region, with its hot summers, warm winters, and often dry spells, influences the climate of the southwest. Due to its location, the Eurasian region is vulnerable to a variety of climate-related natural disasters, including heatwaves, droughts, riverine floods, windstorms, and large-scale wildfires.

Historical Runs

One of the most important basic model experiments conducted within the CMIP project in order to control the model large-scale trends is piControl (Eyring et al, 2016). With 1850 as the reference year, PiControl experiment (Eyring et al, 2016) is conducted in conditions chosen to be typical of the period prior to the onset of large-scale industrialization. Perturbed state of the INMCM model at the end of the piControl is taken as the initial condition for historical runs. The historical experiment is conducted in the context of changing external natural and anthropogenic forcings. Prescribed time series include:

♦ greenhouse gases concentration,

♦ the solar spectrum and total solar irradiance,

♦ concentrations of volcanic sulfate aerosol in the stratosphere, and

♦ anthropogenic emissions of SO2, black, and organic carbon.

The ensemble of historical experiments consists of 10 members for each model version. The duration of each run is 165 model years from 1850 to 2014.

SSP3-7.0 Scenario

Experiments are designed to simulate possible future pathways of climate evolution based on assumptions about human developments including: population, education, urbanization, gross domestic product (GDP), economic growth, rate of technological developments, greenhouse gas (GHG) and aerosol emissions, energy supply and demand, land-use changes, etc. (Riahi et al, 2016). Shared Socio-economic Pathways or “SSP” vary from very ambitious mitigation and increasing shift toward sustainable practices (SSP1) to fossil-fueled development (SSP5) (O’Neill et al, 2016).

Here we discuss climate changes for scenario SSP3-7.0 only, to avoid presentation large amount of information. The SSP3-7.0 scenario reflects the assumption on the high GHG emissions scenario and priority of regional security, leading to societies that are highly vulnerable to climate change, combined with relatively high forcing level (7.0 W/m2 in 2100). On this path, by the end of the century, average temperatures have risen by 3.0–5.5◦C above preindustrial values (Tebaldi et al, 2021). The ensembles of historical runs with INMCM5 and INMCM6 were prolonged for 2015-2100 using scenario SSP3-7.0.

Observational data and data processing

Model near surface temperature and specific humidity changes were compared with ERA5 reanalysis data (Hersbach et al, 2020), precipitation data were compared with data of GPCP (Adler et al, 2018), sea ice extent and volume data were compared with satellite obesrvational data NSIDC (Walsh et al, 2019) and the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS) (Schweiger et al, 2011) respectively, land snow area was compared with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate Data Record (NOAA CDR) of Snow Cover Extent (SCE) reanalysis (Robinson et al, 2012) based on the satellite observational dataset Estilow et al (2015). Following Khan et al (2024) Northern Eurasia is defined as land area lying within boundaries of 35N–75N, 20E–180E. Following IPCC 6th Assessment Report (Masson-Delmotte et al, 2021), the following time horizons are distinguished: the recent past (1995– 2014), near term (2021–2040), mid-term (2041–2060), and long term (2081–2100). To compare observed and model temperature and specific humidity changes in the recent past, data for years 1991–2020 were compared with data for years 1961–1990.

Near surface air temperature change

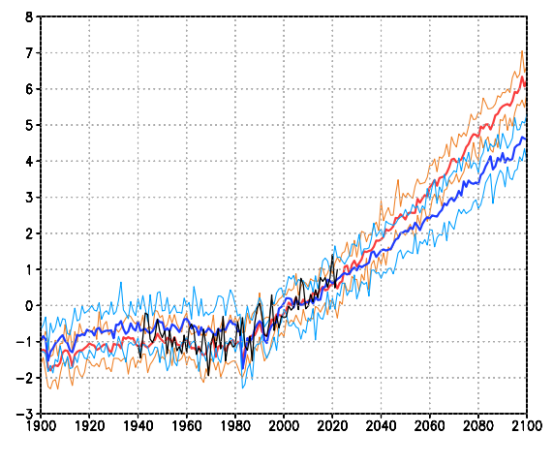

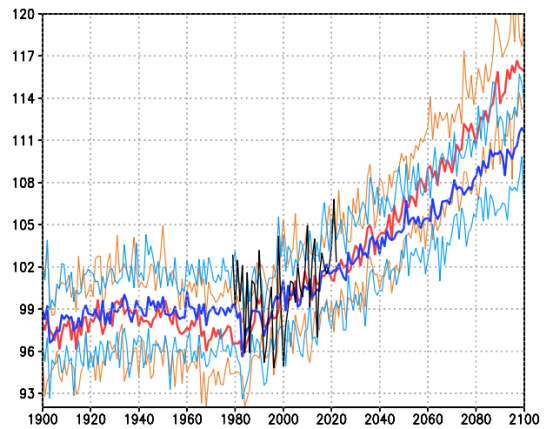

Fig. 1 Annual near surface air temperature change in Northern Eurasia with respect to 1995–2014 for INMCM6 (red), INMCM5 (blue) and ERA5 reanalysis (Hersbach et al, 2020)(black), K. Orange and lightblue lines show ensemble spread.

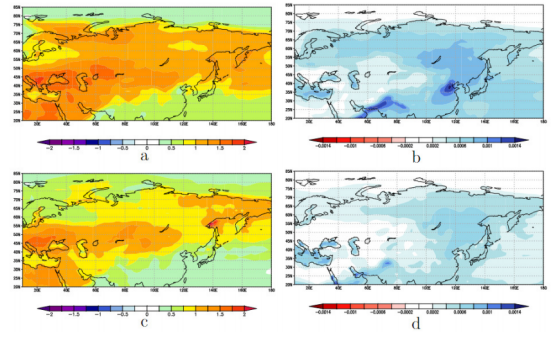

Despite different ECS, both model versions show (Fig. 1) approximately the same warming over Northern Eurasia by 2010–2015, similar to observations. However, projections of Northern Eurasia temperature after year 2040 differ. By 2100, the difference in 2-m air temperature anomalies between two model versions reaches around 1.5 K. The greater value around 6.0 K is achieved by a model with higher sensitivity. This is consistent with Huusko et al (2021); Grose et al (2018); Forster et al (2013), which confirmed that future projections show a stronger relationship than historical ones between warming and climate sensitivity. In contrast to feedback strength, which is more important in forecasting future temperature change, historical warming is more associated with model forcing. Both INMCM5 and INMCM6 show distinct seasonal warming patterns. Poleward of about 55N the seasonal warming is more pronounced in winter than in summer (Fig. 2). That means the smaller amplitude of the seasonal temperature cycle in 1991– 2020 compared to 1961–1990. The same result was shown in Dwyer et al (2012) and Donohoe and Battisti (2013). The opposite situation is observed during the hemispheric summer, where stronger warming is observed over the Mediterranean region (Seager et al, 2014; Kr¨oner et al, 2017; Brogli et al, 2019), subtropics and midlatitudinal regions of the Pacific Ocean, leading to an amplification of the seasonal cycle. The spatial patterns of projected warming in winter and summer in model historical experiments for 1991-2020 relative to 1961-1990 are in a good agreement with ERA5 reanalysis data, although for ERA5 the absolute values of difference are greater.

East Atlantic/West Russia (EAWR) Index

The East Atlantic/West Russia (EAWR) pattern is one of the most prominent large-scale modes of climate variability, with centers of action on the Caspian Sea, North Sea, and northeast China. The EOF-analysis identifies the EAWR pattern as the tripole with different signs of pressure (or 500 hPa geopotential height) anomalies encompassing the aforementioned region.

In this study, East Atlantic/ West Russia (EAWR) index was calculated as the projection coefficient of monthly 500 hPa geopotential height anomalies to the second EOF of monthly reanalysis 500 hPa geopotential height anomalies over the region 20N–80N, 60W–140E.

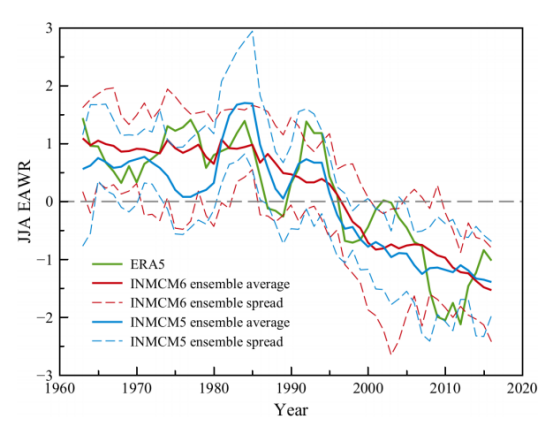

Fig. 5 Time series of June-July-August 5-year mean East Atlantic/ West Russia (EAWR) index. Maximum and minimum of the model ensemble are shown as a dashed lines. INMCM6 and INMCM5 ensemble averaged indices are plotted as a red and blue solid lines, respectively. The ERA5 (Hersbach et al, 2020) EAWR index is shown in green.

[Note: High EAWR index indicates low pressure and cooler over Western Russia, high pressure and warmer over Europe. Low EAWR index is the opposite–high pressure and warming over Western Russia, low pressure and cooling over Europe.]

East Atlantic/ West Russia (EAWR) index Time series of EAWR index can be seen in Fig. 5. Since the middle of 1990s the sign of EAWR index has changed from positive to negative according to reanalysis data. Both versions of the INMCM reproduce the change in the sign of EAWR index. Therefore, the corresponding climate change in the Mediterranean and West Russia regions should be expected. Actually, the difference in annual mean near-surface temperature and specific humidity between 2001–2020 and 1961–1990 shows warmer and wetter conditions spreading from the Eastern Mediterranean to European Russia both for INMCM6 and INMCM5 with the largest difference being observed for the new version of model.

Fig. 6 Annual mean near surface temperature, K (left) and specific humidity, kg/kg (right) in 2001– 2020 with respect to 1961–1990 for INMCM6 (a,b) and INMCM5 (c,d).

Fig. 7 Annual precipitation change (% with respect to 1995–2014) in Northern Eurasia for INMCM6 (red), INMCM5 (blue) and GPCP analysis (Adler et al, 2018) (black). Orange and lightblue lines show ensemble spread.

Discussion and conclusions

Climate changes during the last several decades and possible climate changes until 2100 over Northern Eurasia simulated with climate models INMCM5 and INMCM6 are considered. Two model versions differ in parametrisations of cloudiness, aerosol scheme, land snow cover and atmospheric boundary layer, isopycnal diffusion discretisation and dissipation scheme of the horizontal components of velocity. These modifications in atmosphere and ocean blocks of the model have led to increase of ECS to 3.7 K and TCR to 2.2 K, mainly due to modification of cloudiness parameterisation.

Comparison of model data with available observations and reanalysis show that both models simulate observed recent temperature and precipitation changes consistently with observational datasets. The decrement of seasonal temperature cycle amplitude poleward of about 55N and its increase over the Mediterranean region, subtropics, and mid-latitudinal Pacific Ocean regions are two distinct seasonal warming patterns that are displayed by both INMCM5 and INMCM6. In the long-term perspective, the amplification of difference in projected warming during June-JulyAugust (JJA) and December-January-February (DJF) increases. Both versions of the INMCM reproduce the observed change in the sign of EAWR index from positive to negative in the middle of 1990s, that allows to expect correct reproduction of the corresponding climate change in the Mediterranean and West Russia regions.

Specifically, the enhanced precipitation in the North Eurasian region since the mid-1990s has led to increased specific humidity over the Eastern Mediterranean and European Russia, which is simulated by the INMCM5 and INMCM6 models. Both versions of model correctly reproduce the precipitation change and continue its increasing trend onwards.

Both model versions simulate similar temperature, precipitation, Arctic sea ice extent in 1990–2040 in spite of INMCM5 having much smaller ECS and TCR than INMCM6. However, INMCM5 and INMCM6 show differences in the long-term perspective reproduction of climate changes. After 2040, model INMCM6 simulated stronger warming, stronger precipitation change, stronger Arctic sea ice and land snow extent decrease than INMCM5.

My Comment

So both versions of the model replicate well the observed history. And when fed the SSP3-7.0 inputs, both project a warmer, wetter world out to 2100; INMCM5 reaches 4.5C and INMCM6 gets to 6.0C. The scenario achieves the desired high warming, and the cloud enhancements in version 6 amplify it. I would like to see a similar experiment done with the actual medium scenario SSP2-4.5.

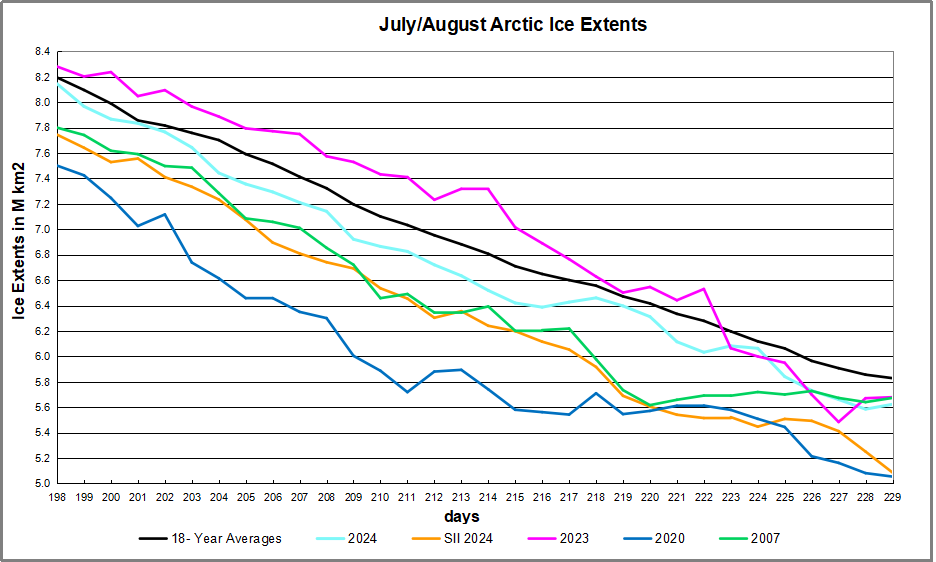

The table below shows the distribution of Sea Ice on day 229 across the Arctic Regions, on average, this year and 2007. At this point in the year, Bering and Okhotsk seas are open water and thus dropped from the table.

The table below shows the distribution of Sea Ice on day 229 across the Arctic Regions, on average, this year and 2007. At this point in the year, Bering and Okhotsk seas are open water and thus dropped from the table.