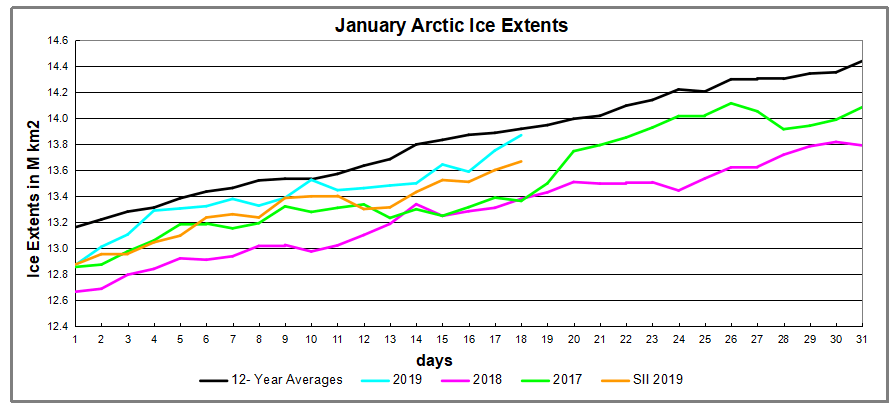

Open image in new tab to enlarge.

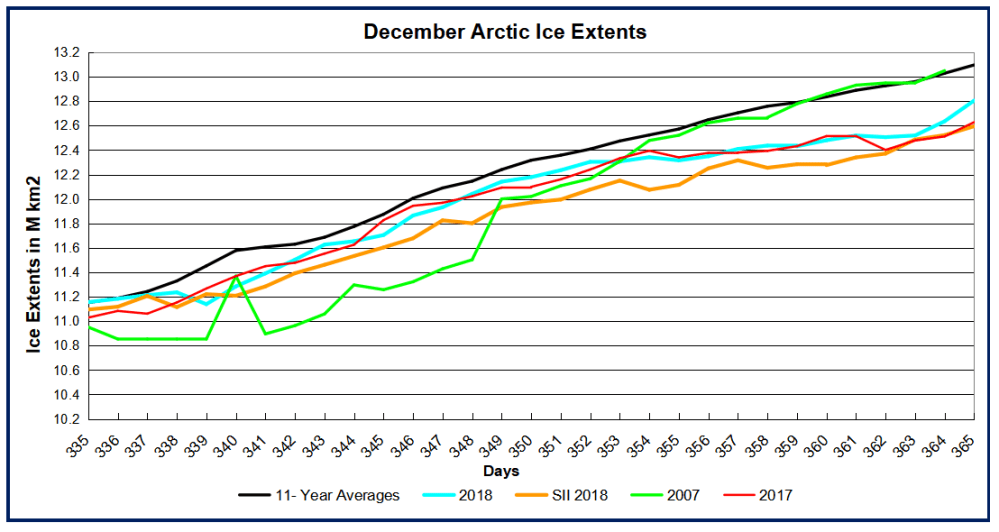

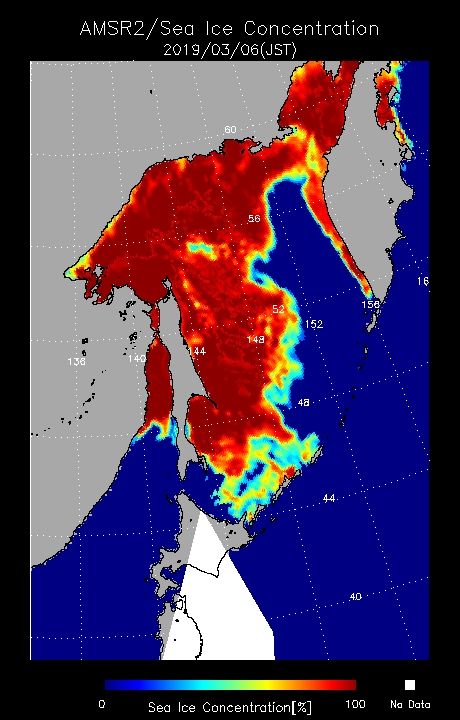

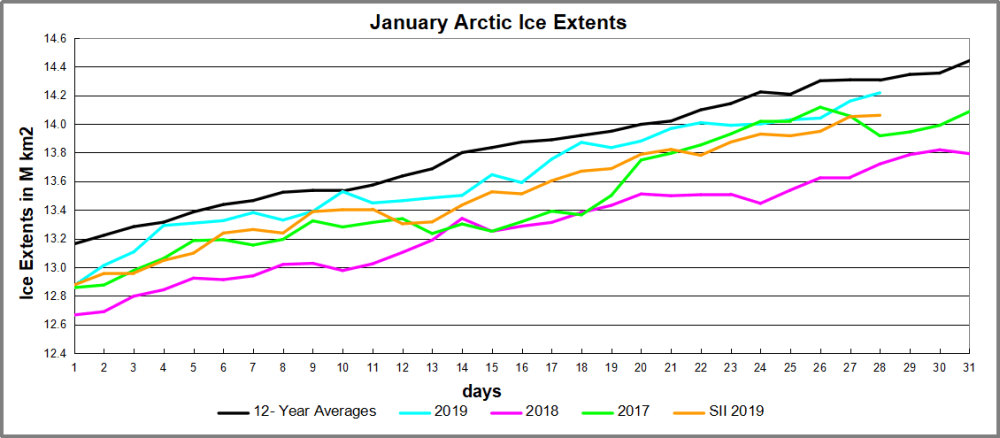

The image shows ice extents on January 7 for the last three years. The two Pacific basins are Bering Sea on the right and Okhotsk on the left. In recent years they had less ice coinciding with the warm Blob in the North Pacific, but it is obvious how strongly Bering is freezing this year. Together they are tracking the combined 12 year average, and Okhotsk is growing ice strongly along the Kamchatka peninsula dividing the two seas.

An updated outlook for the NH winter comes on January 7, 2019 from Dr. Judah Cohen of AER Arctic Oscillation and Polar Vortex Analysis and Forecasts Excerpts with my bolds.

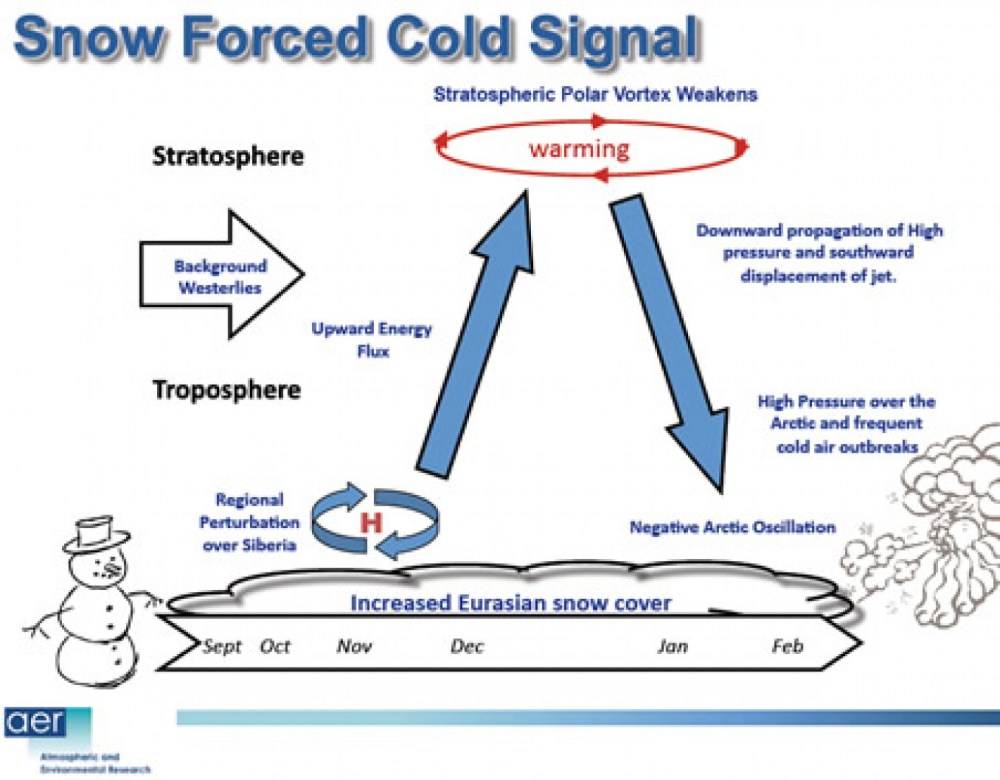

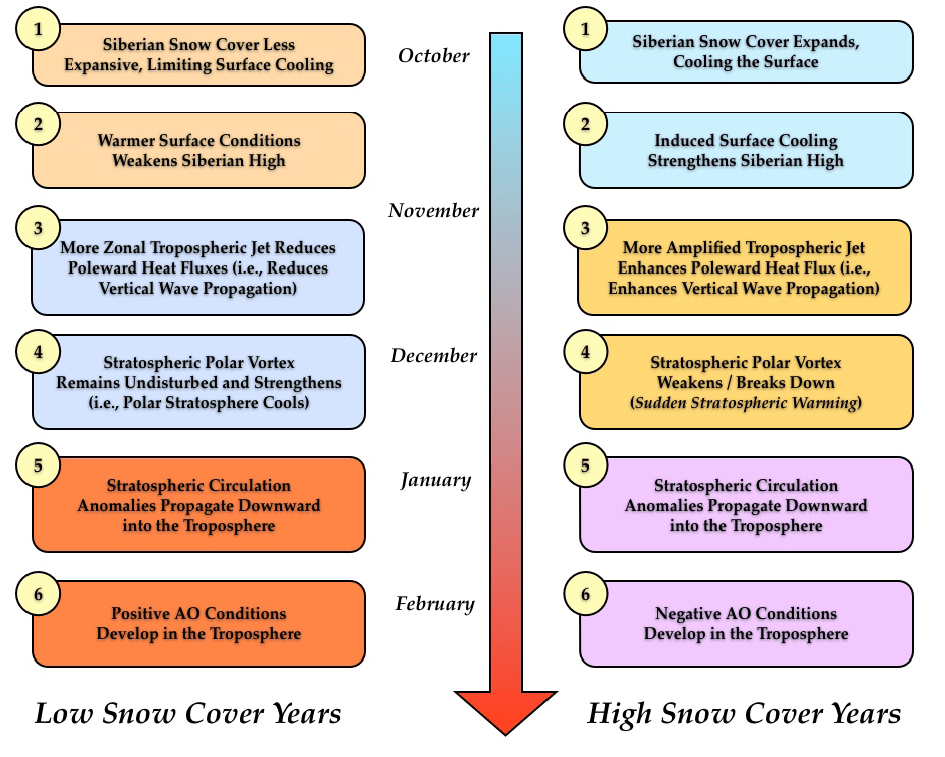

I have once again received some attention for a forecast of a PV (Polar Vortex) disruption to be followed by widespread severe winter weather. After the winter of 2005/06, I know that I cannot guarantee an outcome no matter how tantalizing close it seems to the finish line. That winter, all six steps in our model verified and yet the forecast busted, at least for the Eastern US. And I think the lessons from that winter are applicable to this winter. There has been a lot of discussion, at least on Twitter, will the stratospheric PV split couple to the surface. I don’t think the question is whether the stratosphere and troposphere will couple, there is already strong evidence that they are coupling. The stratospheric and troposphere PVs are vertically stacked as I showed in a tweet earlier today and can be seen from plots below. Furthermore, the most anomalous cold and snowfall across the NH are currently co-located with those PVs.

Looking forward it looks like the coupling will strengthen over time. The GFS is predicting the first “drip” of warm polar cap geopotential height anomalies from the stratosphere to the troposphere at the end of the week and this weekend which is reflected in a short term drop in the AO. The GFS is predicting more “dripping” for the following weekend though more uncertainty exists with any event beyond a week. But regardless how robust the stratosphere-troposphere coupling currently looks, the magnitude and duration on the NH weather is still highly uncertain. And in an attempt to troll me, Mother Nature has delivered a PV split that is very much reminiscent of the PV split in winter 2006 (see Figure iii).

Figure iii. a) Observed 10 mb geopotential heights (contours) and geopotential height anomalies (m; shading) for 1 – 3 February 2006 and b) Observed 500 mb geopotential heights (contours) and geopotential height anomalies (shading) for 1 – 28 February 2006.

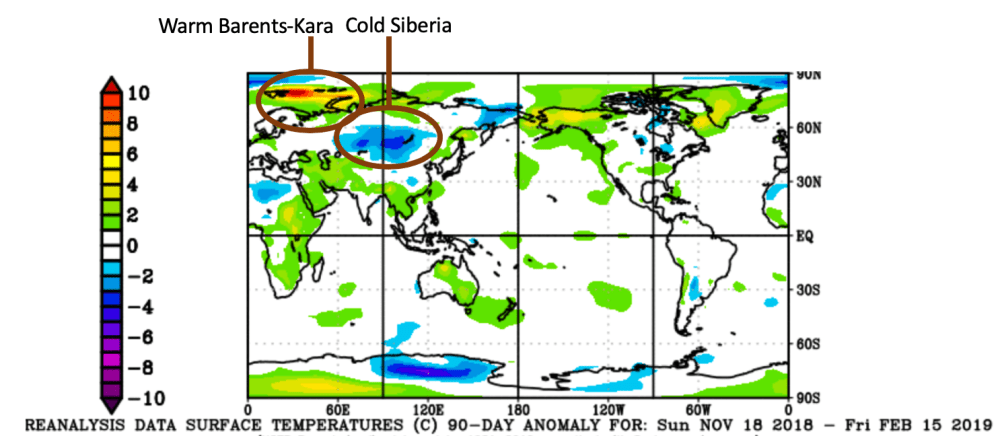

I believe that for a robust tropospheric and weather response to the stratospheric PV split a warm Arctic in the lower to mid-troposphere is critical. If I were to make a winter forecast for winter 2005/06, I would still make the same forecast and I still don’t understand what went wrong with the forecast that winter. In Figure iii I also include the 500 mb geopotential height pattern from that winter and in contrast to the stratosphere the mid-troposphere remained cold in the Central Arctic with low pressure right over the North Pole. Surprisingly, to me at least, the Arctic in the low to mid-troposphere has been relatively cold this winter and for the most part, the forecasts are for that to continue. I think the warmer the Arctic relative to normal over the coming weeks the more likely severe winter weather including cold and snow to be widespread across the NH.

Troughing/negative geopotential height anomalies previously centered near Alaska and the Gulf of Alaska are predicted to continue to drift towards the Dateline supporting ridging/positive geopotential height anomalies downstream over western North America centered over Western Canada with more troughing/negative geopotential height anomalies across eastern North America (Figure 5b). This will favor normal to above normal temperatures across Western Canada and the Western US with normal to below normal temperatures for the Eastern US and especially Eastern Canada (Figure 8). The ECMWF model is predicting less amplified ridging in western North America with milder temperatures in the Eastern US.

Currently the stratospheric PV has broken into several pieces or daughter vortices. The major daughter vortex is centered near Scandinavia and a minor daughter vortex is centered over Quebec and New England with a possible third daughter vortex over the North Pacific with ridging and accompanying warming centered in the Beaufort Sea (Figure 12). The daughter vortex over Scandinavia is predicted to drift west and further split into two with one vortex over Northwest Russia and another over Western Europe with the other vortex over Quebec and New England drifting west into Central Canada.

Figure 12. (a) Analyzed 10 mb geopotential heights (dam; contours) and temperature anomalies (°C; shading) across the Northern Hemisphere for 7 January 2019. (b) Same as (a) except forecasted averaged from 13 – 17 January 2019. The forecasts are from the 00Z 7 January 2019 GFS operational model.

The predicted details of the stratospheric PV disruption are showing better consistency among the weather models. An MMW (Major Mid-winter Warming) has occurred as well as a PV split. Instead there still remains much uncertainty with the impacts of the stratospheric warming on the weather. Following the peak of the stratospheric warming, I would expect the warm/positive PCHS to “drip” down into the troposphere, which is now predicted by at least the GFS. A sudden stratospheric warming not only leads to a warm Arctic in the stratosphere but also at the surface as well. And a warmer Arctic favors more severe winter weather in the NH midlatitudes including the Eastern US. I do think there is uncertainty how warm much the Arctic warms in the lower troposphere and surface and could play a major role in the duration and magnitude of the weather impacts of the PV split.

Figure 9. Forecasted snowfall anomalies (mm/day; shading) from 18 – 22 January 2019. The forecasts are from the 00Z 7 January 2019 GFS ensemble.

Figure 9. Forecasted snowfall anomalies (mm/day; shading) from 18 – 22 January 2019. The forecasts are from the 00Z 7 January 2019 GFS ensemble.

Once again additional snowfall is possible across much of northern Eurasia including Siberia, Western Asia, Scandinavia, Central and even possibly Western Europe (Figure 9). Seasonable to cold temperatures across Eastern Canada and even the Northeastern US will also support potentially new snowfall (Figure 9). Mild temperatures could result in snowmelt across Southeastern Europe, Turkey, Alaska, Western Canada and the Western US (Figure 9).

See Also:Snowing and Freezing in the Arctic

See

See

Figure 9. Forecasted snowfall anomalies (mm/day; shading) from 18 – 22 January 2019. The forecasts are from the 00Z 7 January 2019 GFS ensemble.

Figure 9. Forecasted snowfall anomalies (mm/day; shading) from 18 – 22 January 2019. The forecasts are from the 00Z 7 January 2019 GFS ensemble.