With These Climate Policies, Doing Nothing is the Good

Matthew Lau writes at Financial post When climate policy is all error, doing nothing could be good. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

Matthew Lau writes at Financial post When climate policy is all error, doing nothing could be good. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

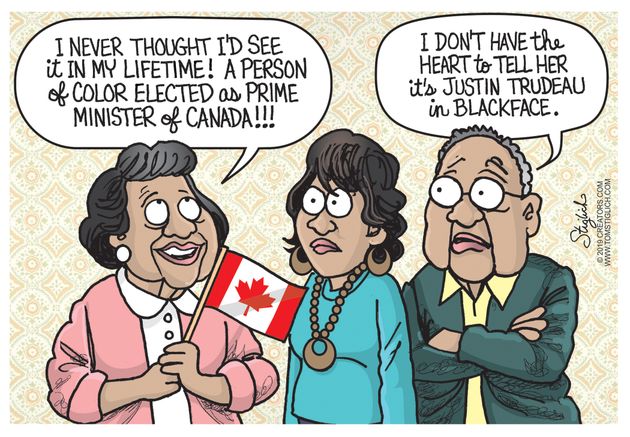

It may not be a bad thing for Canadians that Pierre Poilievre

has been largely quiet on climate and environmental policy

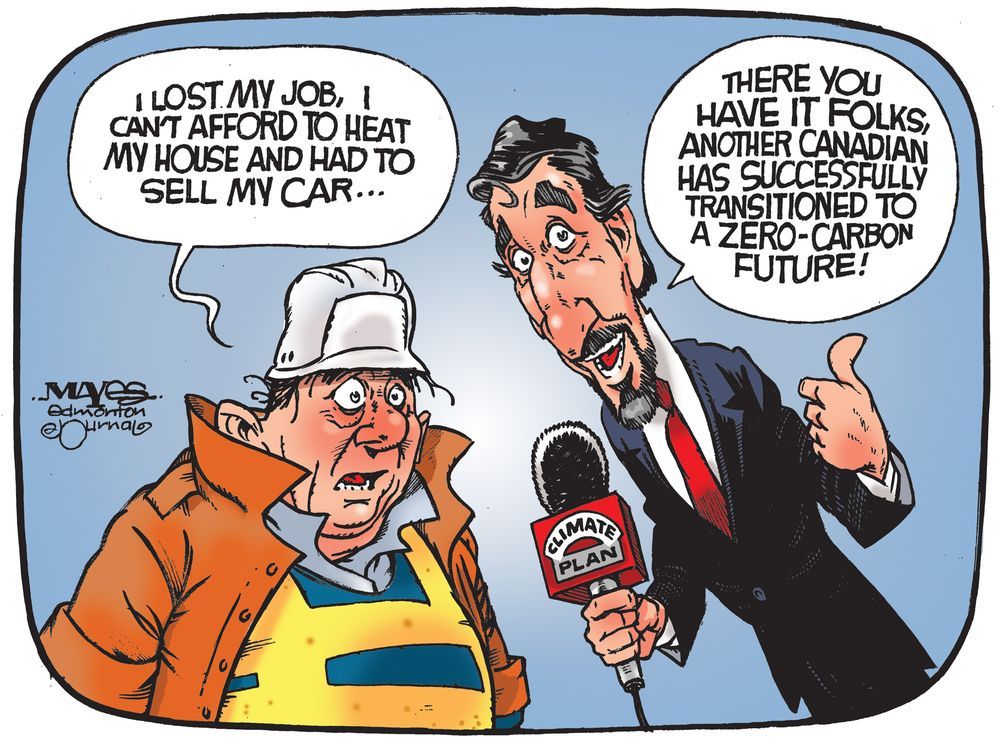

Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre has not proposed much in the way of climate and environmental policy beyond scrapping the carbon tax, but if he is searching for policy ideas, one place he best not look — except for examples of what not to do — is across the pond to the U.K.’s Conservative government. Its environmental agenda is a shambolic mishmash of impoverishing energy policies, climate alarmism, excess spending, and virtue-signalling regulations that afflict consumers and businesses without any compensating environmental benefit.

If all this sounds familiar, it is because Canadians are already suffering

from the same policy agenda under the Liberals.

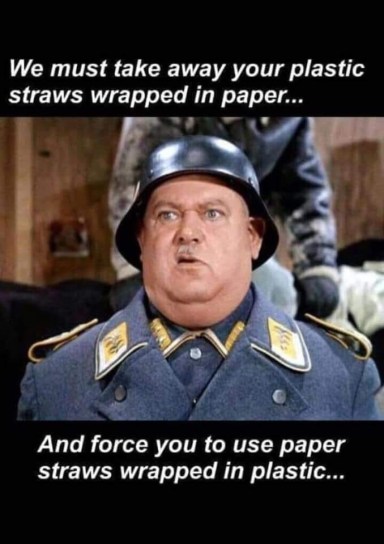

The British government’s latest regulatory effort is a ban on plastic utensils, plates and cups. It follows a 2020 ban on plastic straws, stir sticks and cotton swabs. The latest ban applies only to restaurants and cafes, as the government is planning a separate policy for grocery store sales of the same products next year. It is a little inconsistent that people can still buy bulk packages of plastic forks at the grocery store while not being allowed to access a single fork at a restaurant, where they might actually want to use it. But having two sets of policies implemented a year apart lets the government maximize bureaucrat-hours and so keep the public sector happy.

The problems with plastic bans are well documented.

First, plastic pollution is overwhelmingly caused by waste management problems, primarily in Asia, not single-use products in developed countries. As reported in Reason, the U.K. accounts for only 0.05 per cent of global marine plastic waste.

Second, the alternatives to single-use plastics are more expensive and of lower quality.

Third, despite decomposing more quickly, the alternatives are also often worse for the environment overall. A 2018 Danish Environmental Protection Agency study found that in order to be better for the environment than a plastic bag a conventional cotton bag would have to be re-used 7,100 times.

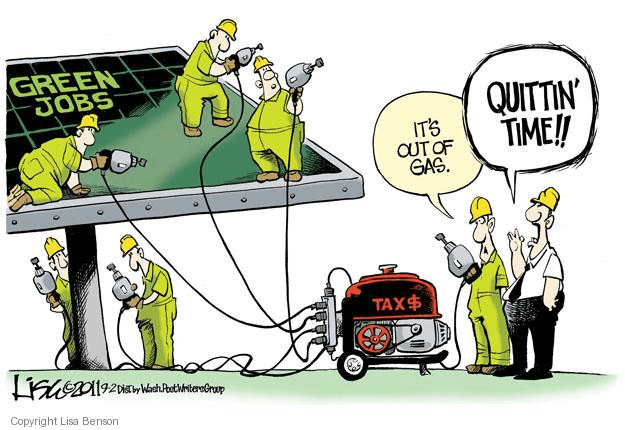

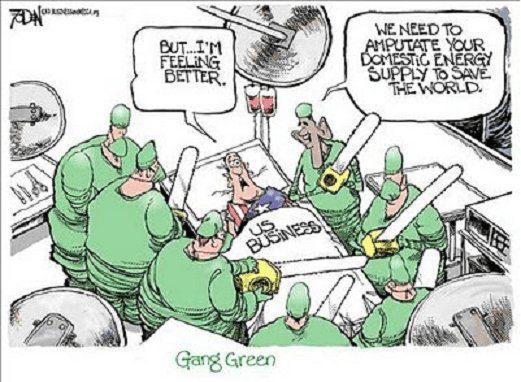

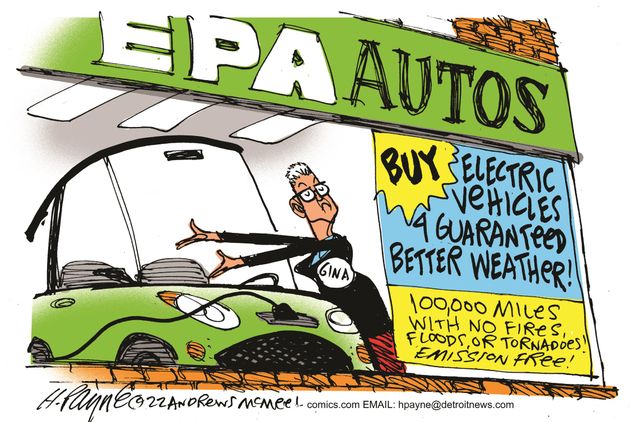

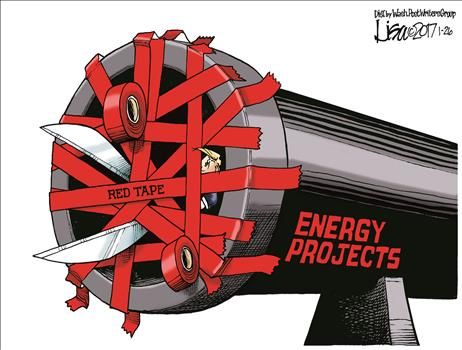

The environmental policy madness pursued by the U.K. Conservatives and similarly hopeless governments, like the Liberals in Canada, extends past the war on plastic to the war on gasoline-powered cars. In Canada, the federal government plans to mandate that at least 60 per cent of new vehicles sold must be electric by 2030, and by 2035 the sale of all new gasoline-powered vehicles will be banned. The U.K.’s mandate is even worse, as in 2020 then-prime minister Boris Johnson, for reasons unknown, decided to advance the date for banning gasoline-powered cars from 2035 (the year selected by the EU) to 2030. Hybrids will be banned by 2035.

As the Telegraph reports, government enthusiasm for switching to electric vehicles is not matched by consumer enthusiasm: higher price tags and rising electricity prices have flattened demand. A green energy group that three months ago forecast 360,000 electric vehicles would be manufactured in the U.K. by 2025 has just slashed its estimate to 280,000. Unfortunately, consumer reluctance has not stopped the government from trying to control motorists’ behaviour in order to achieve its climate ambitions. A report earlier this month from the U.K. Parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee on accelerating the transition away from fossil fuels proposed such measures as a public information campaign to lecture motorists on driving more efficiently, cutting speed limits, imposing “car-free Sundays” in large cities and car-sharing.

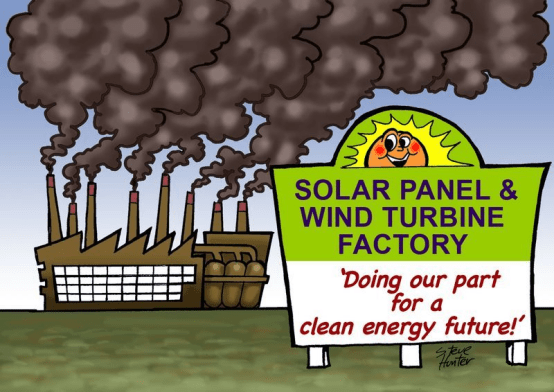

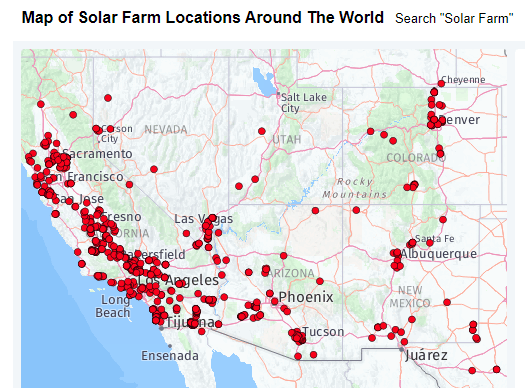

Philip Dunne, the Conservative MP who chairs the committee, declared the U.K. needs “a national war effort” to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, in addition to the hassling of motorists there will be many more billions in spending, “green mortgages,” a call for all housing developers to fit solar panels on new houses as standard and other governmental interventions, all in pursuit of the “guiding star” of net-zero emissions by 2050. The 99-page report is not entirely bereft of reason, but as National Review’s Andrew Stuttaford concludes, it appears to be written by people who learned too little “from the economic and geopolitical disaster that Europe’s climate policy-makers have done so much to enable” and its overall direction is to push Britain faster down the path of more poverty and less freedom.

In view of all this, it may not be a bad thing for Canadians that Pierre Poilievre has been largely quiet on climate and environmental policy. A children’s book of Winnie-the-Pooh-inspired wisdom once offered the suggestion, “Don’t underestimate the value of doing nothing.”

Given the climate-policy disasters of governments of all stripes in Europe, the U.K., and Canada seeking to do something, doing nothing may not be bad advice.

/img/iea/r1OrW3DQGn/evs-in-cold.jpg)