Update May 19, 2015 text added at end.

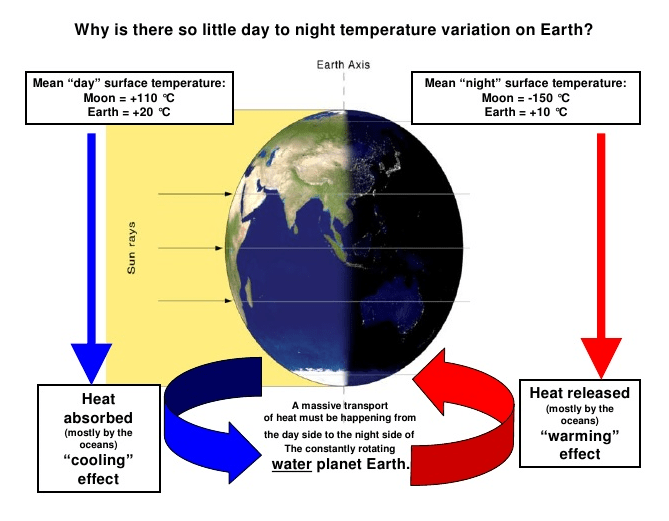

Earlier I wrote an essay about our living on a water world. Then an essay described the role of oceans as a climate flywheel, storing massive amounts of solar energy and thereby stabilizing fluctuations in temperature and climate. A recent post about oceans making global temperature changes drew some comments about downplaying the role of the atmosphere in climate change. So I want to clarify some things.

The Dynamic Duo

Climate change is a coupled ocean-air dynamic, stimulated by ocean heat transfers into the air, and involving the two fluids (air and water) feeding off each other.

To maintain an approximate steady state climate the ocean and atmosphere must move excess heat from the tropics to the heat deficit polar regions. Additionally the ocean and atmosphere must move freshwater to balance regions with excess dryness with those of excess rainfall. The movement of freshwater in its vapor, liquid and solid state is referred to as the hydrological cycle.

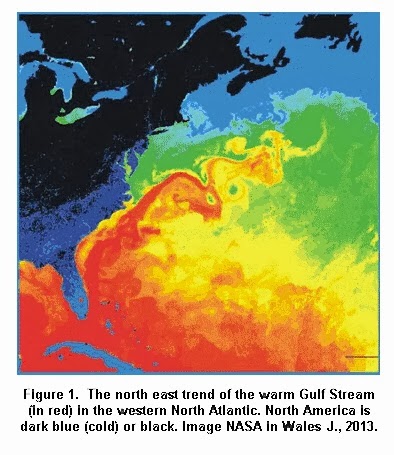

In low latitudes the ocean moves more heat poleward than does the atmosphere, but at higher latitudes the atmosphere becomes the big carrier. The wind driven ocean circulation moves heat mainly on the horizontal plane. For example, in the North Atlantic, warm surface water move northward within the Gulf Stream on the western side of the ocean, to be balanced by cold surface water moving southward within the Canary Current on the eastern side of the ocean. The thermohaline circulation moves heat mainly in the vertical plane. For example, North Atlantic Deep Water with a temperature of about 2°C flows towards the south in the depth range 2000 to 4000 meters to be balanced by warmer water (greater than 4°C) flowing northward within the upper 1000 meters.

The ocean role in climate would be zero if there were an impervious lid over the ocean, but there is not, across the sea surface pass heat, water, momentum, gases and other materials. The wind exerts a stress on the sea surface that induces the Ekman transport and wind driven circulation.

http://eesc.columbia.edu/courses/ees/climate/lectures/o_atm.html

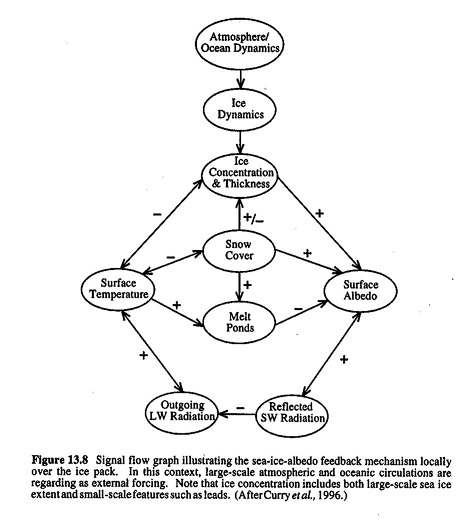

A lot of factors affect heat transfers from oceans to atmosphere, but the main ones are advection (heat in water flowing horizontally), mixing (vertical upwelling and downwelling of warmer and colder waters) and surface evaporation (latent heat rising with water vapor converted from liquid). The latter is greatly affected by wind which adds to the complexity of the process. For this essay, I will leave on the side the issue of sea ice dynamics, including the latent heat released in its freezing.

Ocean-atmosphere Interactions

The ocean can warm or cool the air in a number of different ways. For example, when the air is at a lower temperature than seawater, the ocean transfers heat to the lower atmosphere, which becomes less dense as the heat causes molecules in the air to move farther apart. As a result, a low-pressure air mass forms over that part of the ocean. (Conversely, cool or cold waters lead to the formation of high-pressure air masses as air molecules move closer together.) Because air always flows from areas of higher pressure to those of lower pressure, winds are diverted toward the low-pressure area.

Among winds that are affected by such pressure changes are the jet streams, bands of fast-moving, high-altitude air currents. Jet streams supply energy to developing storms at lower altitudes and then influence their movement. In this way, the ocean alters the direction of storm tracks. Some storms even reverse direction as the result of ocean-influenced air-pressure changes.

The ocean’s currents make it possible for these weather effects to be widely distributed. Some currents carry warm water from tropical and subtropical regions toward the poles, while other currents move cool water in the opposite direction. The Gulf Stream is a current that transports warm water across the North Atlantic Ocean from Florida toward Europe. Before reaching Europe, the Gulf Stream breaks up into several other currents, one of which flows to the British Isles and Norway. The heat carried in this current warms the winds that blow over these regions, helping to keep winters there from becoming bitterly cold.

In this way, the ocean’s circulation compensates somewhat for the sun’s unequal heating of the Earth, in which the tropics receive more energy from the sun than the poles. Were it not for the moderating effects of ocean currents on air temperatures, the tropics would be much hotter than they are and the polar regions even colder.

Besides transferring heat to the atmosphere, the ocean also adds water to the air through evaporation. When the sun’s heat causes surface water to evaporate, warm water vapor rises into the atmosphere. As the water vapor rises higher, it cools into tiny water droplets and ice crystals, which collect together to form large clouds. The clouds soon return their moisture to the surface as rain, snow, sleet, or hail. Most evaporation occurs in the warm waters of the tropics and subtropics, providing moisture for tropical storms.

Virtually all rain comes from the evaporation of seawater. Though this may seem surprising, it makes sense when one considers that about 97 percent of all water on Earth is in the ocean. The Earth’s water cycle, or hydrologic cycle, consists largely of the never-ending circulation of water from the ocean to the atmosphere and then back to the ocean.

http://science.howstuffworks.com/how-the-ocean-affects-climate-info1.htm

Oceanic Oscillations

Most widely known is the El Nino Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. Many other naturally occurring ocean-atmosphere oscillations in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans have been recognized and named. Some of them have much more of an impact on climate and weather patterns in the U.S. and elsewhere than ENSO. As during ENSO, in many of these ocean and atmosphere interact as a coupled system, with ocean conditions influencing the atmosphere and atmospheric conditions influencing the ocean. However, not all exert as strong an influence on global weather patterns, and some are even less regular than ENSO.

Many oscillations are under study:

Antarctic Oscillation (AAO), also referred to as the Southern Annular Mode (SAM).

Arctic Oscillation (AO)

The AO and the North Atlantic Oscillation (see below) are collectively referred to as the Northern Annular Mode (NAM).

Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)

Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)

Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO)

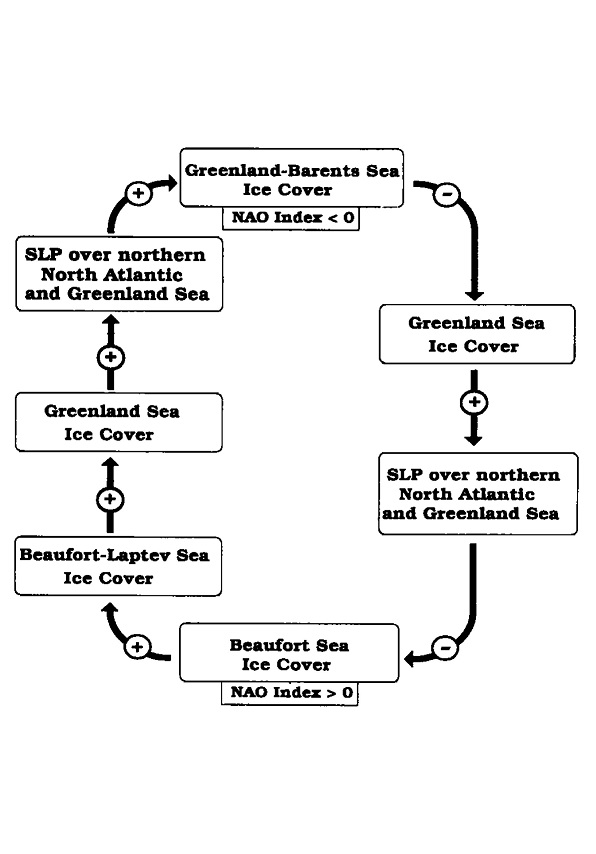

North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)

North Pacific Gyre Oscillation (NPGO)

North Pacific Oscillation (NPO)

Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)

Pacific-North American (PNA) Pattern

http://www.whoi.edu/main/topic/el-nino-other-oscillations

Each of these patterns has its distinctive qualities, ranging from phases lasting a month or so to multi-decadal phases. Some fundamental features can be seen in all of them:

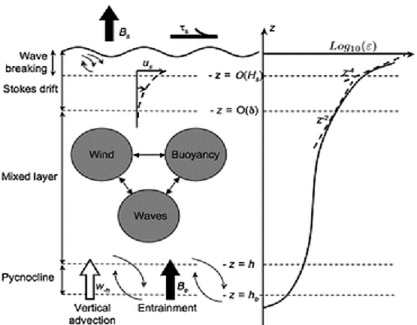

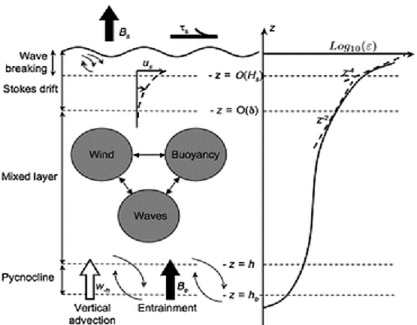

The diagram shows the vertical structure of the ocean surface boundary layer (OSBL) and the processes that deepen. The three sources of turbulence are: wind, buoyancy and waves.

The bulk of the OSBL can be termed the mixed layer, where the temperature and salinity are approximately uniform with depth, and which is often capped below, at the mixed layer depth, by a sharp pycnocline, which extends deeper into the ocean. Three sources of turbulence, namely wind, buoyancy and waves, drive turbulence in this mixed layer, which then deepens the OSBL. Hence a quantitative understanding of these turbulent processes in the OSBL is likely to be the key to understanding the shallow biases in mixed layer depth.

Deepening of the OSBL implies an increase in potential energy, and hence requires an energy source, such as turbulent kinetic energy (TKE).

Belcher, S. E., et al. (2012), A global perspective on Langmuir turbulence in the ocean surface boundary

layer, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L18605, doi:10.1029/2012GL052932.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2012GL052932/full

The Madden-Julian Oscillation is one of the simpler oscillations to understand, partly because of its short 30-60 day cycle.

Even so, you can see there is a lot going on, and a lot of variables affecting both strength and timing. But the same dynamic plays out in all the oscillations, including ENSO.

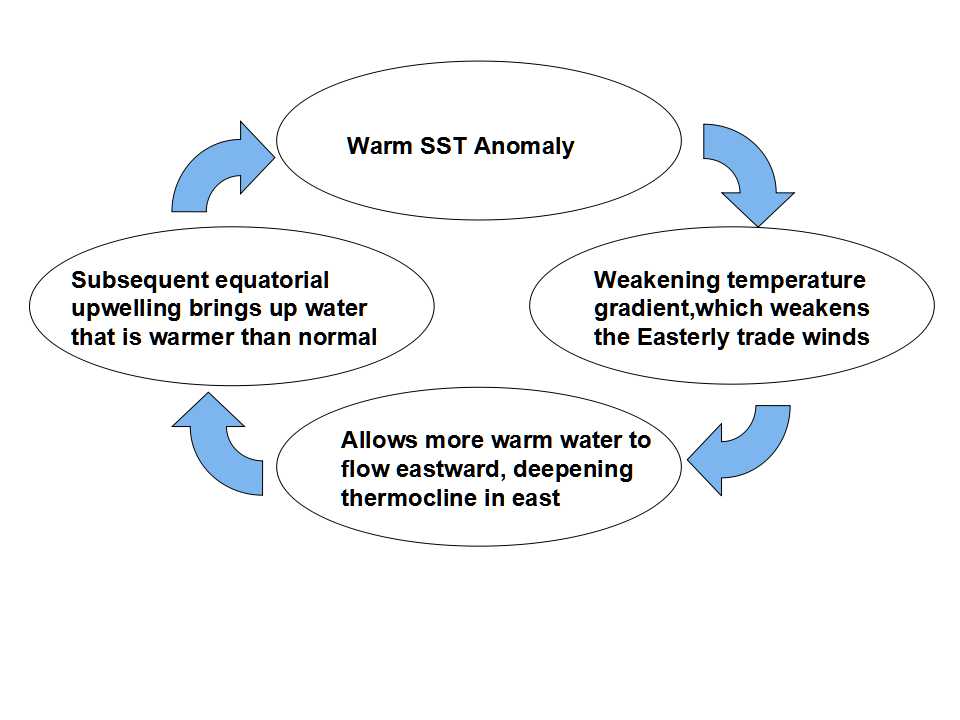

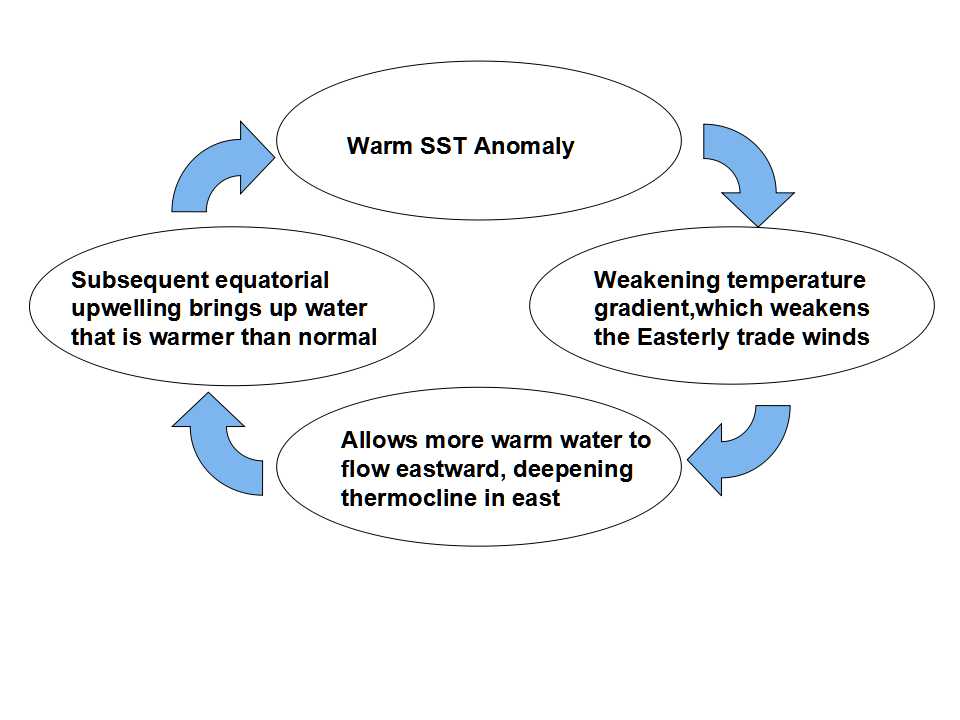

First, the atmosphere responds to the ocean: the atmospheric fluctuations manifested as the Southern Oscillation are mostly an atmospheric response to the changed lower boundary conditions associated with El Nino SST fluctuations.

Second, the ocean responds to the atmosphere: the oceanic fluctuations manifested as El Nino seem to be an oceanic response to the changed wind stress distribution associated with the Southern Oscillation.

Third, the El Nino-Southern Oscillation phenomenon arises spontaneously as an oscillation of the coupled ocean-atmosphere system.

Once the El Nino event is fully developed, negative feedbacks begin to dominate the Bjerknes positive feedback, lowering the SST and bringing the event to its end after several months.

Schematic of the feedback inherent in the Pacific Ocean-atmosphere interaction. This has become known as the Bjerknes feedback.

When ocean and atmospheric conditions in one part of the world change as a result of ENSO or any other oscillation, the effects are often felt around the world. The rearrangement of atmospheric pressure, which governs wind patterns, and sea-surface temperature, which affects both atmospheric pressure and precipitation patterns, can drastically rearrange regional weather patterns, occasionally with devastating results.

Because it affects ocean circulation and weather, an El Niño or La Niña event can potentially lead to economic hardships and disaster. The potential is made worse when these combine with another, often overlooked environmental problem. For example, overfishing combined with the cessation of upwelling during an El Niño event in 1972 led to the collapse of the Peruvian anchovy fishery.

Extreme climate events are often associated with positive and negative ENSO events. Severe storms and flooding have been known to ravage areas of South America and Africa, while intense droughts and fires have occurred in Australia and Indonesia during El Niño events.

http://faculty.washington.edu/kessler/occasionally-asked-questions.html

Summary

The picture that emerges from this analysis is that the wind-driven meridional overturning circulation in the upper Pacific Ocean has been slowing down since the 1970s. This slowdown can account for the recent anomalous surface warming in the tropical Pacific, as the supply of cold pycnocline water originating at higher latitudes to feed equatorial upwelling has decreased. The Southern Hemisphere is responsible for about half of the observed decrease in equatorward pycnocline transport. Thus, perspectives on decadal variability limited to the Northern Hemisphere alone are incomplete. The fact that few studies have considered a role for the Southern Hemisphere ocean is presumably a consequence of limited data availability rather than a lack of decadal signal in the southern tropics and Subtropics.

The oceanic and atmospheric processes that we have described work together so as to reinforce each other, similar to the positive feedbacks that occur during ENSO events. For example, weaker easterly trade winds in the equatorial Pacific would result in reduced Ekman and geostrophic meridional transports, reduced equatorial upwelling, and warmer equatorial sea surface temperatures. Warmer surface temperatures in turn would alter patterns of deep atmospheric convection so as to favour weaker trade winds. If the system is to oscillate on decadal timescales, then delayed negative feedback mechanisms, one candidate for which involves planetary scale ocean waves, must also be important.

Similarities in the spatial structures of the PDO and ENSO (both, for example, have phases that are characterized by warm tropics and a cool central North Pacific, and vice versa) have raised questions about the possible interaction between interannual- and decadal timescale phenomena in the Pacific. In particular, since 1976±77 there have been fewer La Nina events, and more frequent, stronger, and longer-lasting El Nino events.

Whether this recent change in the character of the ENSO cycle is a consequence or a cause of underlying decadal-timescale variability is unknown. It could be that the decadal changes in circulation described here operate independently from those that affect the ENSO cycle. If so, they would modify the background state on which ENSO develops, and thereby precondition interannual fluctuations to preferred modes of

behaviour. Alternatively, the observed decadal changes may simply be the low-frequency residual of random or chaotic fluctuations in tropical ocean±atmosphere interactions that give rise to the ENSO cycle itself. In either case, a complete understanding of climate variability spanning interannual to decadal timescales in the Pacific basin will need to account for the slowly varying meridional overturning circulation between the tropics and subtropics.

Click to access mcphaden+zhang_nature_2002.pdf

Conclusion

Ocean oscillations are profoundly uncertain, not only because each one is erratic in the timing and strength of phase changes, but also because they have interactive effects upon each other. And with time cycles differing from 1-2 months to 30-60 years the complexity of movements is enormous.

Even today, after many years of study by highly intelligent people, the factors are murky enough that coupled ocean-atmospheric models still lack skill to forecast the patterns. And so, in 2015, we find advocates for reducing use of fossil fuels hoping and praying for a warm water blob in the Northern Pacific to intensify or endure so that the average global temperature will trend higher than last year.

Of course, the satellite records have 1998 as the warmest year by a wide margin. And why was that year so warm? It was a super El Nino. This is Oceans making climate, no mistake about it.

Update May 19, 2015

Dr. William Gray adds the longer term context to these oscillations in his 2012 paper:

“The global surface warming of about 0.7°C that has been experienced over the last 150 years and the multi-decadal up-and-down global temperature changes of 0.3-0.4°C that have been observed over this period are hypothesized to be driven by a combination of multi-century and multi-decadal ocean circulation changes. These ocean changes are due to naturally occurring upper ocean salinity variations. Changes in CO2 play little role in these salinity driven ocean climate forcings. “

Many ocean-climate dynamics are explained in Dr. Gray’s paper:

http://tropical.atmos.colostate.edu/Includes/Documents/Publications/gray2012.pdf

Included are excellent diagrams and charts, such as these:

The Dynamic Duo: Ocean and Air

Oceans make climate is by partnering with the atmosphere. It’s a match made in heaven: Ocean is dense, powerful, slow and constrained; Atmosphere is thin, light, fast and free. Ocean has solar heat locked in its Abyss, Atmosphere is open to the cold of space. Together they take on the mission of spreading energy far and wide from the equator to the poles, and into space, the final frontier.

Here’s how it goes. Working together as companion fluids, and feeding off each other, they make winds, waves, weather and climate.

But make no mistake: Ocean is Batman, Atmosphere is Robin; Ocean is Captain Kirk, Atmosphere is Spock; Ocean the dog, Atmosphere the tail.

As for the villainous CO2, that does not rise to the level of Joker or Penguin; CO2 is probably best cast as the Riddler:

The RAPID moorings being deployed. Credit: National Oceanography Centre

The RAPID moorings being deployed. Credit: National Oceanography Centre