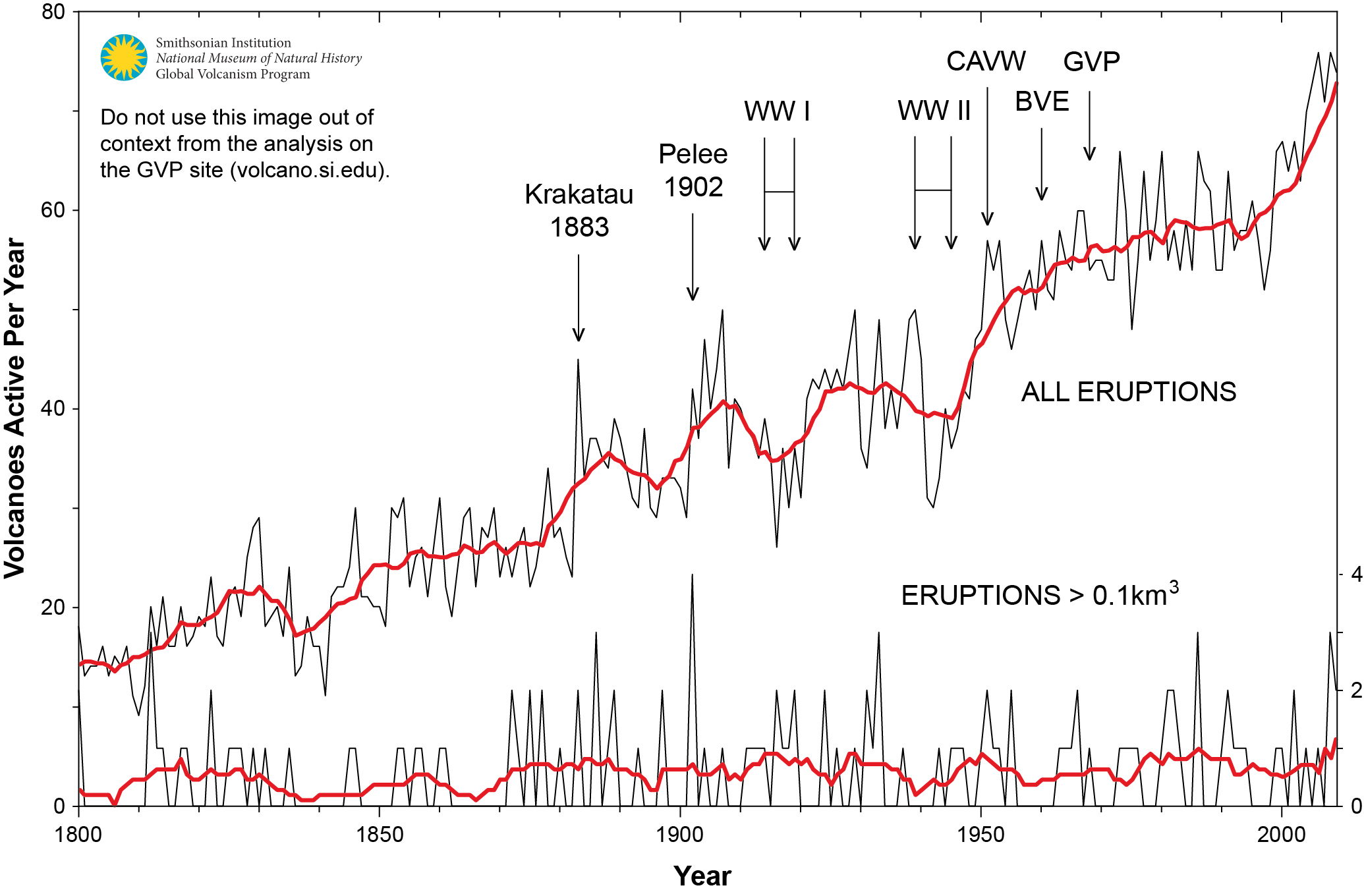

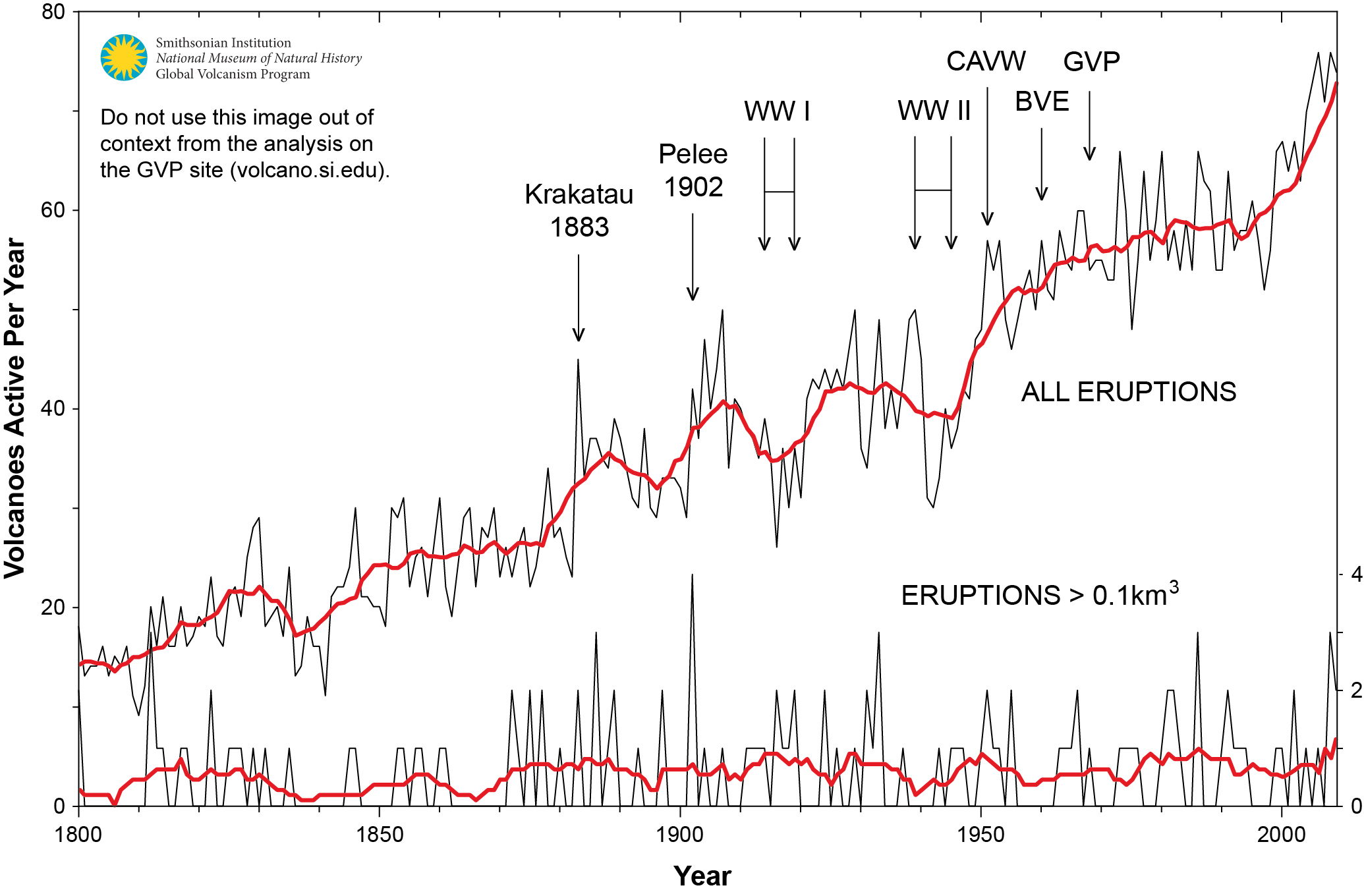

Figure 1. Graph showing the number of volcanoes reported to have been active each year since 1800 CE. Total number of volcanoes with reported eruptions per year (thin upper black line) and 10-year running mean of same data (thick upper red line). Lower lines show only the annual number of volcanoes producing large eruptions (>= 0.1 km3 of tephra or magma) and scale is enlarged on the right axis; thick red lower line again shows 10-year running mean. Global Volcanism Project Discussion

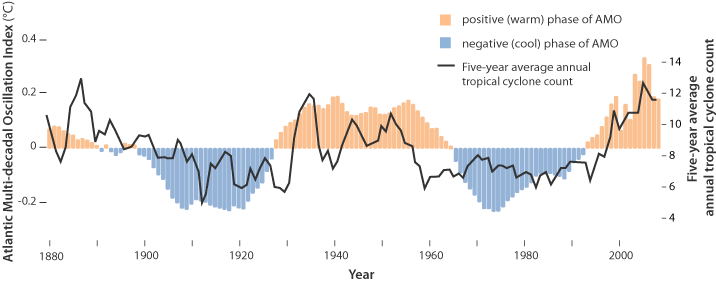

Thanks to Dr. Francis Manns for drawing my attention to the role of Volcanoes as a climate factor, particularly related to the onset of the Little Ice Age (LIA), 1400 to 1900 AD. I was aware that the temperature record since about 1850 can be explained by a steady rise of 0.5C per century rebound overlaid with a quasi-60 year cycle, most likely oceanic driven. See below Dr. Syun Akasofu 2009 diagram from his paper Two Natural Components of Recent Warming.

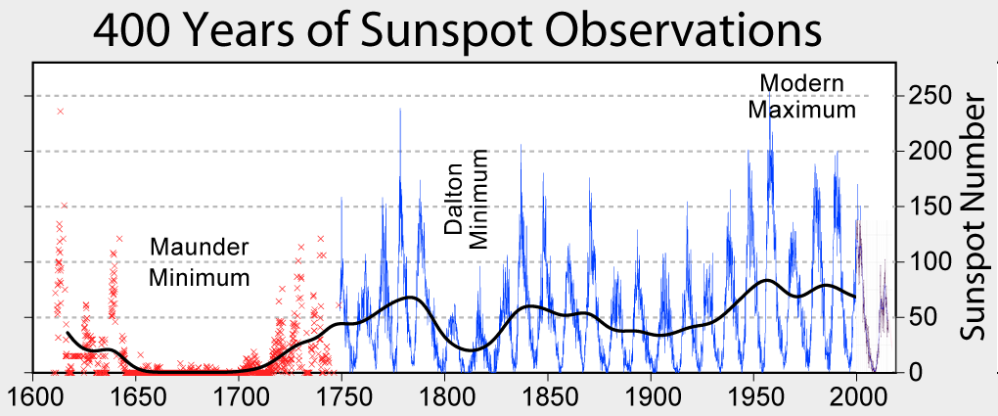

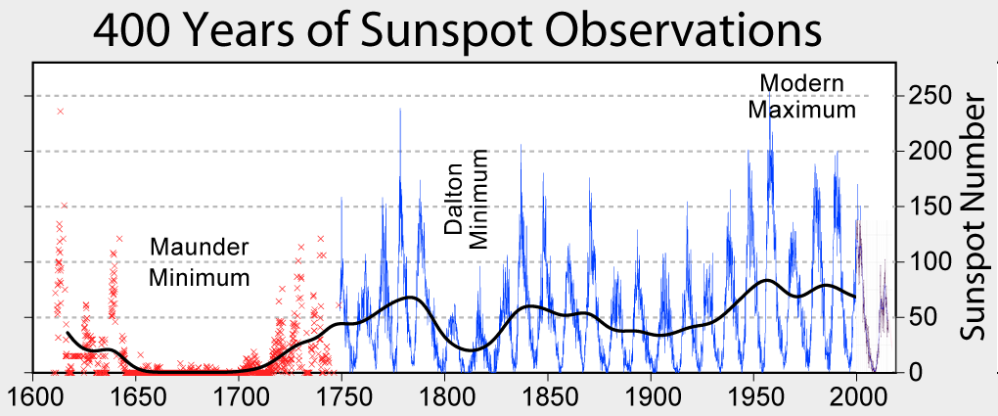

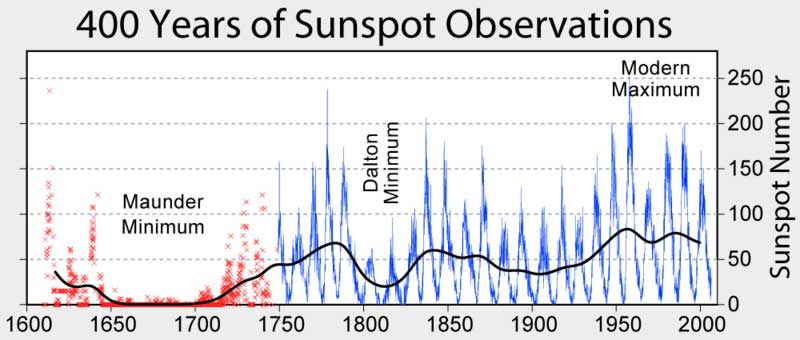

When I presented this diagram to my warmist friends, they would respond, “But you don’t know what caused the LIA or what ended it!” To which I would say, “True, but we know it wasn’t due to burning fossil fuels.” Now I find there is a body of evidence suggesting what caused the LIA and why the temperature rebound may be over. Part of it is a familiar observation that the LIA coincided with a period when the sun was lacking sunspots, the Maunder Minimum.

When I presented this diagram to my warmist friends, they would respond, “But you don’t know what caused the LIA or what ended it!” To which I would say, “True, but we know it wasn’t due to burning fossil fuels.” Now I find there is a body of evidence suggesting what caused the LIA and why the temperature rebound may be over. Part of it is a familiar observation that the LIA coincided with a period when the sun was lacking sunspots, the Maunder Minimum.

Not to be overlooked is the climatic role of volcano activity inducing deep cooling patterns such as the LIA. Jihong Cole-Dai explains in a paper published 2010 entitled Volcanoes and climate. Excerpt in italics with my bolds.

There has been strong interest in the role of volcanism during the climatic episodes of Medieval Warm Period (MWP,800–1200 AD) and Little Ice Age (LIA, 1400–1900AD), when direct human influence on the climate was negligible. Several studies attempted to determine the influence of solar forcing and volcanic forcing and came to different conclusions: Crowley and colleagues suggested that increased frequency of stratospheric eruptions in the seventeenth century and again in the early nineteenth century was responsible in large part for LIA. Shindell et al. concluded that LIA is the result of reduced solar irradiance, as seen in the Maunder Minimum of sunspots, during the time period. Ice core records show that the number of large volcanic eruptions between 800 and 1100 AD is possibly small (Figure 1), when compared with the eruption frequency during LIA. Several researchers have proposed that more frequent large eruptions during the thirteenth century(Figure 1) contributed to the climatic transition from MWP to LIA, perhaps as a part of the global shift from a warmer to a colder climate regime. This suggests that the volcanic impact may be particularly significant during periods of climatic transitions.

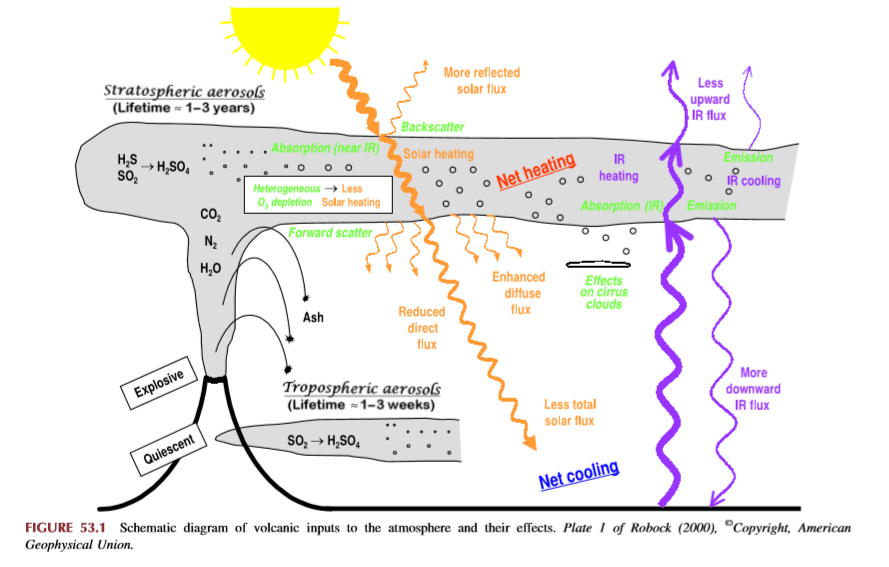

How volcanoes impact on the atmosphere and climate

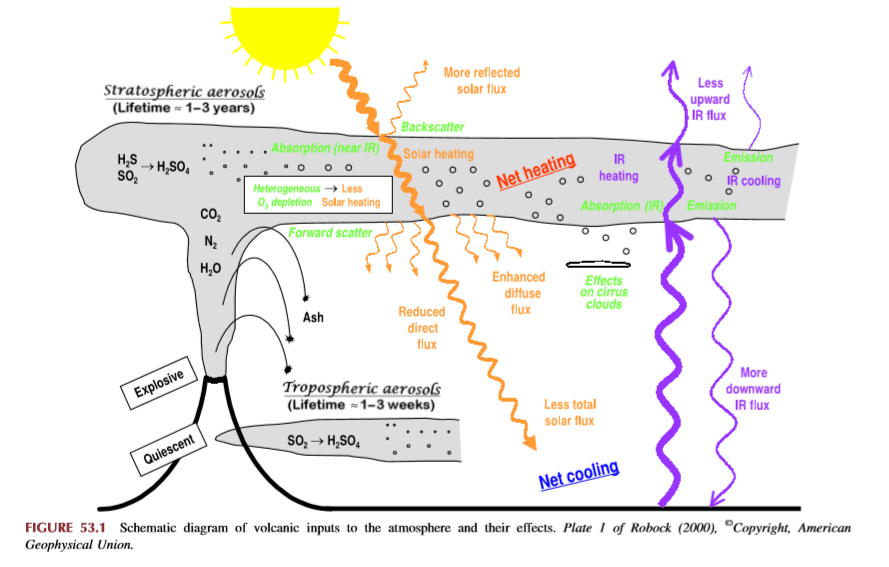

Alan Robock explains Climatic Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions in Chapter 53 of the Encyclopedia of Volcanoes. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

The major component of volcanic eruptions is the matter that emerges as solid, lithic material or solidifies into large particles, which are referred to as ash or tephra. These particles fall out of the atmosphere very rapidly, on timescales of minutes to a few days, and thus have no climatic impacts but are of great interest to volcanologists, as seen in the rest of this encyclopedia. When an eruption column still laden with these hot particles descends down the slopes of a volcano, this pyroclastic flow can be deadly to those unlucky enough to be at the base of the volcano. The destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum after the AD 79 Vesuvius eruption is the most famous example.

Volcanic eruptions typically also emit gases, with H2O, N2, and CO2 being the most abundant. Over the lifetime of the Earth, these gases have been the main source of the Earth’s atmosphere and ocean after the primitive atmosphere of hydrogen and helium was lost to space. The water has condensed into the oceans, the CO2 has been changed by plants into O2 or formed carbonates, which sink to the ocean bottom, and some of the C has turned into fossil fuels. Of course, we eat plants and animals, which eat the plants, we drink the water, and we breathe the oxygen, so each of us is made of volcanic emissions. The atmosphere is now mainly composed of N2 (78%) and O2 (21%), both of which had sources in volcanic emissions.

Of these abundant gases, both H2O and CO2 are important greenhouse gases, but their atmospheric concentrations are so large (even for CO2 at only 400 ppm in 2013) that individual eruptions have a negligible effect on their concentrations and do not directly impact the greenhouse effect. Global annually averaged emissions of CO2 from volcanic eruptions since 1750 have been at least 100 times smaller than those from human activities. Rather the most important climatic effect of explosive volcanic eruptions is through their emission of sulfur species to the stratosphere, mainly in the form of SO2, but possibly sometimes as H2S. These sulfur species react with H2O to form H2SO4 on a timescale of weeks, and the resulting sulfate aerosols produce the dominant radiative effect from volcanic eruptions.

The major effect of a volcanic eruption on the climate system is the effect of the stratospheric cloud on solar radiation (Figure 53.1). Some of the radiation is scattered back to space, increasing the planetary albedo and cooling the Earth’s atmosphere system. The sulfate aerosol particles (typical effective radius of 0.5 mm, about the same size as the wavelength of visible light) also forward scatter much of the solar radiation, reducing the direct solar beam but increasing the brightness of the sky. After the 1991 Pinatubo eruption, the sky around the sun appeared more white than blue because of this. After the El Chicho´n eruption of 1982 and the Pinatubo eruption of 1991, the direct radiation was significantly reduced, but the diffuse radiation was enhanced by almost as much. Nevertheless, the volcanic aerosol clouds reduced the total radiation received at the surface.

Crowley et al 2008 go into the details in their paper Volcanism and the Little Ice Age. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Although solar variability has often been considered the primary agent for LIA cooling, the most comprehensive test of this explanation (Hegerl et al., 2003) points instead to volcanism being substantially more important, explaining as much as 40% of the decadal-scale variance during the LIA. Yet, one problem that has continually plagued climate researchers is that the paleo-volcanic record, reconstructed from Antarctic and Greenland ice cores, cannot be well calibrated against the instrumental record. This is because the primary instrumental volcano reconstruction used by the climate community is that of Sato et al. (1993), which is relatively poorly constrained by observations prior to 1960 (especially in the southern hemisphere).

Here, we report on a new study that has successfully calibrated the Antarctic sulfate record of volcanism from the 1991 eruptions of Pinatubo (Philippines) and Hudson (Chile) against satellite aerosol optical depth (AOD) data (AOD is a measure of stratospheric transparency to incoming solar radiation). A total of 22 cores yield an area-weighted sulfate accumulation rate of 10.5 kg/km2 , which translates into a conversion rate for AOD of 0.011 AOD/ kg/km2 sulfate. We validated our time series by comparing a canonical growth and decay curve for eruptions for Krakatau (1883), the 1902 Caribbean eruptions (primarily Santa Maria), and the 1912 eruption of Novarupta/Katmai (Alaska)

We therefore applied the methodology to part of the LIA record that had some of the largest temperature changes over the last millennium.

Figure 2: Comparison of 30-90°N version of ice core reconstruction with Jones et al. (1998) temperature reconstruction over the interval 1630-1850. Vertical dashed lines denote levels of coincidence between eruptions and reconstructed cooling. AOD = Aerosol Optical Depth.

The ice core chronology of volcanoes is completely independent of the (primarily) tree ring based temperature reconstruction. The volcano reconstruction is deemed accurate to within 0 ± 1 years over this interval. There is a striking agreement between 16 eruptions and cooling events over the interval 1630-1850. Of particular note is the very large cooling in 1641-1642, due to the concatenation of sulfate plumes from two eruptions (one in Japan and one in the Philippines), and a string of eruptions starting in 1667 and culminating in a large tropical eruption in 1694 (tentatively attributed to Long Island, off New Guinea). This large tropical eruption (inferred from ice core sulfate peaks in both hemispheres) occurred almost exactly at the beginning of the coldest phase of the LIA in Europe and represents a strong argument against the implicit link of Late Maunder Minimum (1640-1710) cooling to solar irradiance changes.

Figure 1: Comparison of new ice core reconstruction with various instrumental-based reconstructions of stratospheric aerosol forcing. The asterisks refer to some modification to the instrumental data; for Sato et al. (1993) and the Lunar AOD, the asterisk refers to the background AOD being removed for the last 40 years. For Stothers (1996), it refers to the fact that instrumental observations for Krakatau (1883) and the 1902 Caribbean eruptions were only for the northern hemisphere. To obtain a global AOD for these estimates we used Stothers (1996) data for the northern hemisphere and our data for the southern hemisphere. The reconstruction for Agung eruption (1963) employed Stothers (1996) results from 90°N-30°S and the Antarctic ice core data for 30-90°S.

During the 18th century lull in eruptions, temperatures recovered somewhat but then cooled early in the 19th century. The sequence begins with a newly postulated unknown tropical eruption in midlate 1804, which deposited sulfate in both Greenland and Antarctica. Then, there are four well-documented eruptions—an unknown tropical eruption in 1809, Tambora (1815) and a second doublet tentatively attributed in part to Babuyan (Philippines) in 1831 and Cosiguina (Nicaragua) in 1835. These closely spaced eruptions are not only large but have a temporally extended effect on climate, due to the fact that they reoccur within the 10-year recovery timescale of the ocean mixed layer.

The ocean has not recovered from the first eruption so the second eruption drives the temperatures to an even lower state.

Implications for Contemporary Climate Science

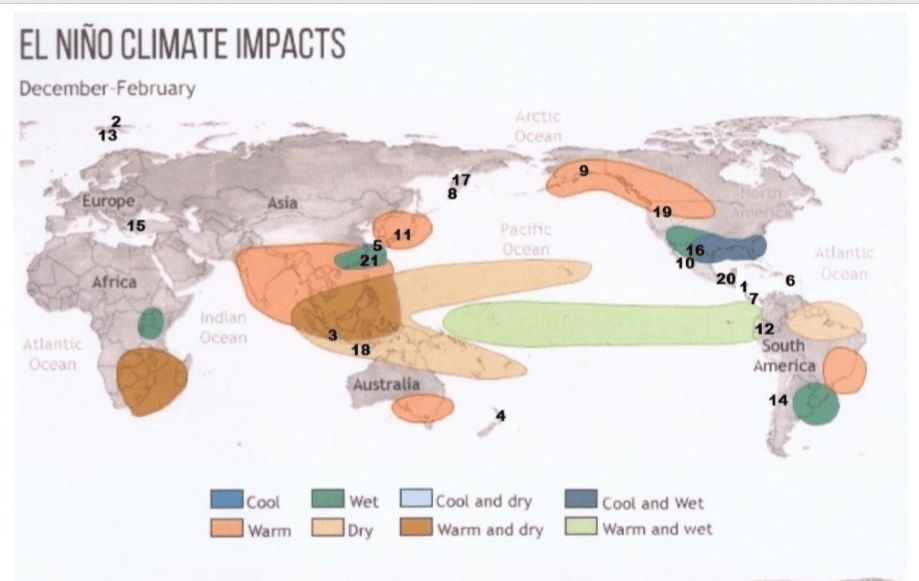

In this context Dr. Francis Manns went looking for a volcanic signature in recent temperature records. His paper is Volcano and Enso Punctuation of North American Temperature: Regression Toward the Mean Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Abstract: Contrary to popular media and urban mythology the global warming we have experienced since the Little Ice Age is likely finished. A review of 10 temperature time series from US cities ranging from the hottest in Death Valley, CA, to possible the most isolated and remote at Key West, FL, show rebound from the Little Ice Age (which ended in the Alps by 1840) by 1870. The United States reached temperatures like modern temperatures (1950 – 2000) by about 1870, then declined precipitously principally caused by Krakatoa, and a series of other violent eruptions. Nine of these time series started when instrumental measurement was in its infancy and the world was cooled by volcanic dust and sulphate spewed into the atmosphere and distributed by the jet streams. These ten cities represent a sample of the millions of temperature measurements used in climate models. The average annual temperatures are useful because they account for seasonal fluctuations. In addition, time series from these cities are punctuated by El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

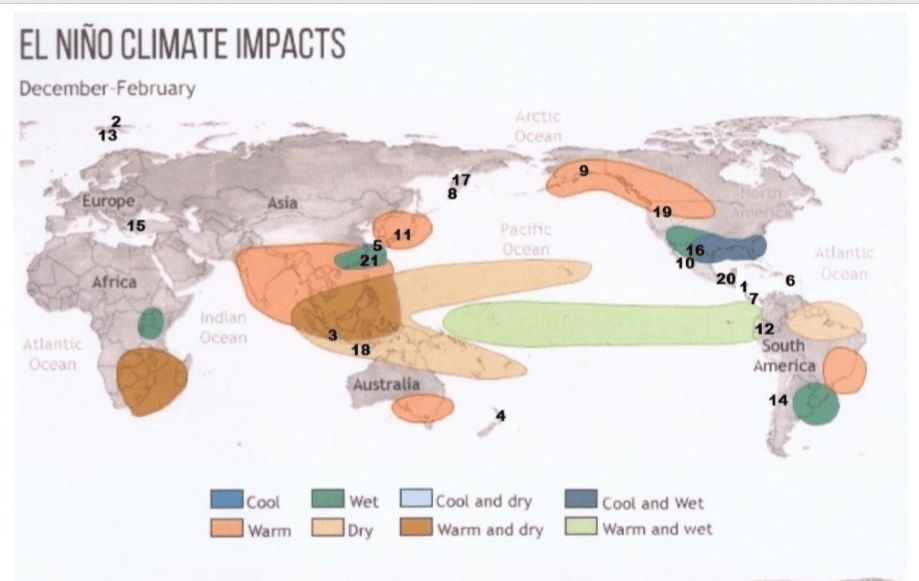

As should be expected, temperature at each city reacted differently to differing events. Several cities measured the effects of Krakatoa in 1883 while only Death Valley, CA and Berkeley CA sensed the minor new volcano Paricutin in Michoacán, Mexico. The Key West time series shows rapid rebound from the Little Ice Age as do Albany, NY, Harrisburg, PA, and Chicago. IL long before the petroleum-industrial revolution got into full swing. Recording at most sites started during a volcanic induced temperature minimum thus giving an impression of global warming to which industrial carbon dioxide is persuasively held responsible. Carbon dioxide, however, cannot be proven responsible for these temperatures. These and likely subsequent temperatures could be the result of regression to the normal equilibrium temperatures of the earth (for now). If one were to remove the volcanic punctuation and El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) input many would display very little alarming warming from 1815 to 2000. This review illustrates the weakness of linear regression as a measure of change. If there is a systemic reason for the global warming hypothesis, it is an anthropogenic error in both origin and termination. ENSO compliments and confirms the validity of NOAA temperature data. Temperatures since 2000 during the current hiatus are not available because NOAA has closed the public website.

Example of time series from Manns. Numbers refer to major named volcano eruptions listed in his paper. For instance, #3 was Krakatoa

The cooling effect is said to have lasted for 5 years after Krakatoa erupted – from 1883 to 1888. Examination of these charts, However, shows that, e.g., Krakatoa did not add to the cooling effect from earlier eruptions of Cosaguina in 1835 and Askja in 1875. The temperature charts all show rapid rebound to equilibrium temperature for the region affected in a year or two at most.

Fourteen major volcanic eruptions, however, were recorded between 1883 and 1918 (Robock, 2000, and this essay). Some erupted for days or weeks and some were cataclysmic and shorter. The sum of all these eruptions from Krakatoa onward effected temperatures early in the instrumental age. Judging from wasting glaciers in the Alps, abrupt retreat began about 1860).

Manns Conclusions:

1)Four of these time series (Albany, Harrisburg, Chicago and Key West) show recovery to the range of today’s temperatures by 1870 before the eruption of Askja in 1875. The temperature rebounded very quickly after the Little Ice Age in the northern hemisphere.

2)Volcanic eruptions and unrelated huge swings shown from ENSO largely rule global temperature. Volcanic history and the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) trump all other increments of temperature that may be hidden in the lists.

3)The sum of the eruptions from Krakatoa (1883) to Katla (1918) and Cerro Azul (1932) was a cold start for climate models.

4)It is beyond doubt that academic and bureau climate models use data that was gathered when volcanic activity had depressed global temperature. The cluster from Krakatoa to Katla (1883 -1918) were global.

5)Modern events, Mount Saint Helens and Pinatubo, moreover, were a fraction of the event intensity of the late 19th and early 20th centuries eruptions.

6) The demise of frequent violent volcanos has allowed the planet to regress toward a norm (for now).

Summary

These findings describe a natural process by which a series of volcanoes along with a period of quiet solar cycles ended the Medieval Warm Period (MWP), chilling the land and inducing deep oceanic cooling resulting in the Little Ice Age. With much less violent volcanic activity in the 20th century, coincidental with typically active solar cycles, a Modern Warm Period ensued with temperatures rebounding back to approximately the same as before the LIA.

This suggests that humans and the biosphere were enhanced by a warming process that has ended. The solar cycles are again going quiet and are forecast to continue that way. Presently, volcanic activity has been routine, showing no increase over the last 100 years. No one knows how long will last the current warm period, a benefit to us from the ocean recovering after the LIA. But future periods are as likely to be cooler than to be warmer compared to the present.

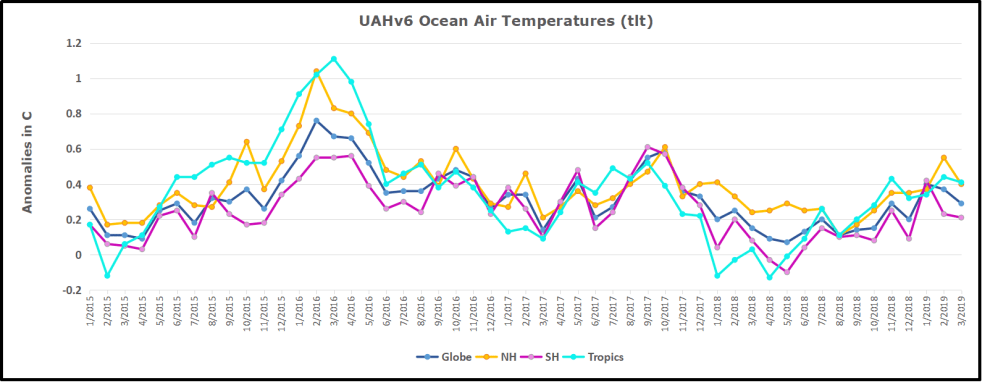

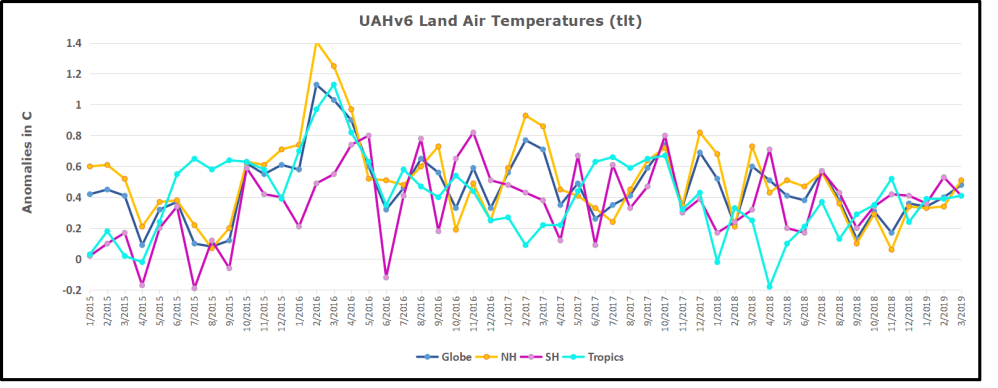

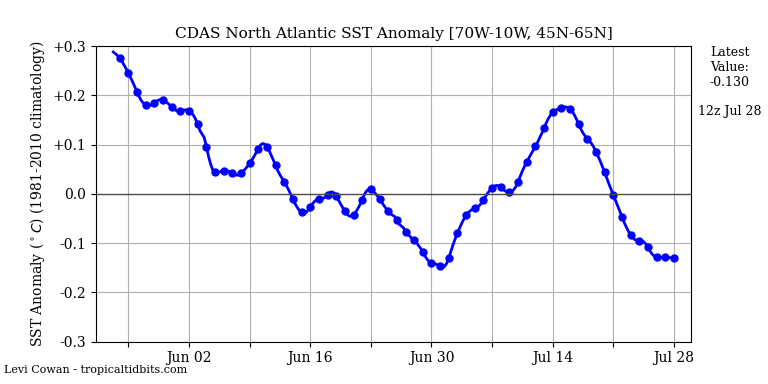

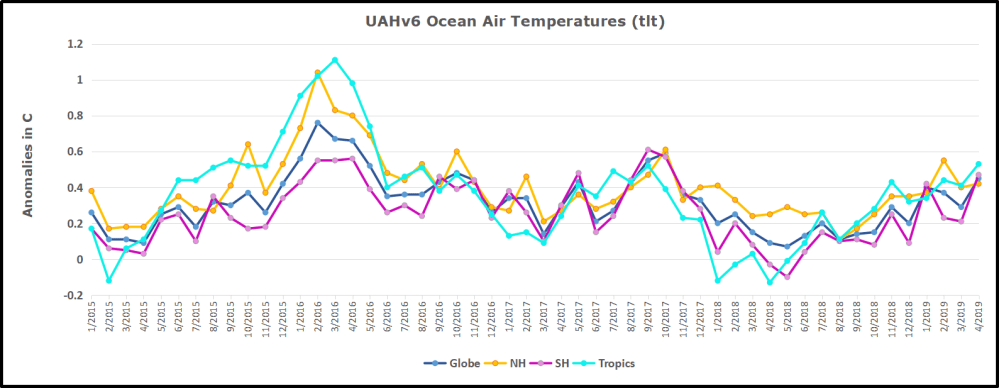

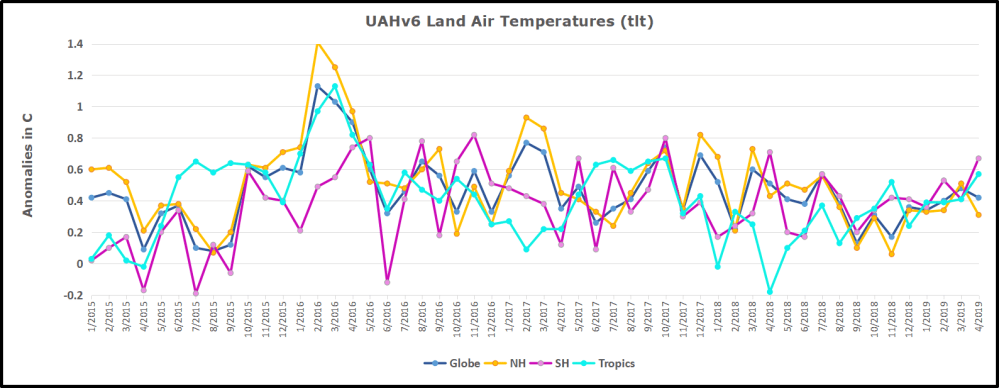

June ocean air temps rose in all regions after May’s drop, resulting in the Global average back up matching June 2017. NH warming in June was slight while warming in SH and the Tropics was stronger. The temps this June are warmer than 2018, similar to 06/2017, and of course lower than 2016.

June ocean air temps rose in all regions after May’s drop, resulting in the Global average back up matching June 2017. NH warming in June was slight while warming in SH and the Tropics was stronger. The temps this June are warmer than 2018, similar to 06/2017, and of course lower than 2016.

When I presented this diagram to my warmist friends, they would respond, “But you don’t know what caused the LIA or what ended it!” To which I would say, “True, but we know it wasn’t due to burning fossil fuels.” Now I find there is a body of evidence suggesting what caused the LIA and why the temperature rebound may be over. Part of it is a familiar observation that the LIA coincided with a period when the sun was lacking sunspots, the Maunder Minimum.

When I presented this diagram to my warmist friends, they would respond, “But you don’t know what caused the LIA or what ended it!” To which I would say, “True, but we know it wasn’t due to burning fossil fuels.” Now I find there is a body of evidence suggesting what caused the LIA and why the temperature rebound may be over. Part of it is a familiar observation that the LIA coincided with a period when the sun was lacking sunspots, the Maunder Minimum.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/0b/1f/0b1f80a6-748b-405a-a08a-5f35e3a59290/ev115-020.jpg)

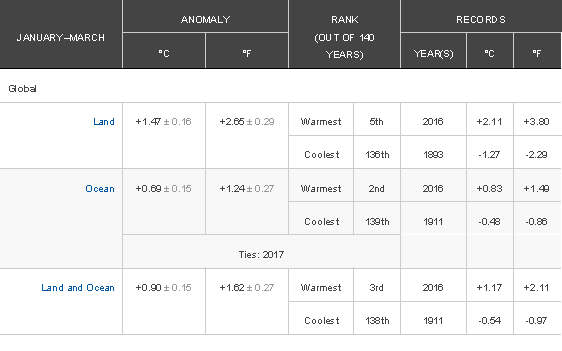

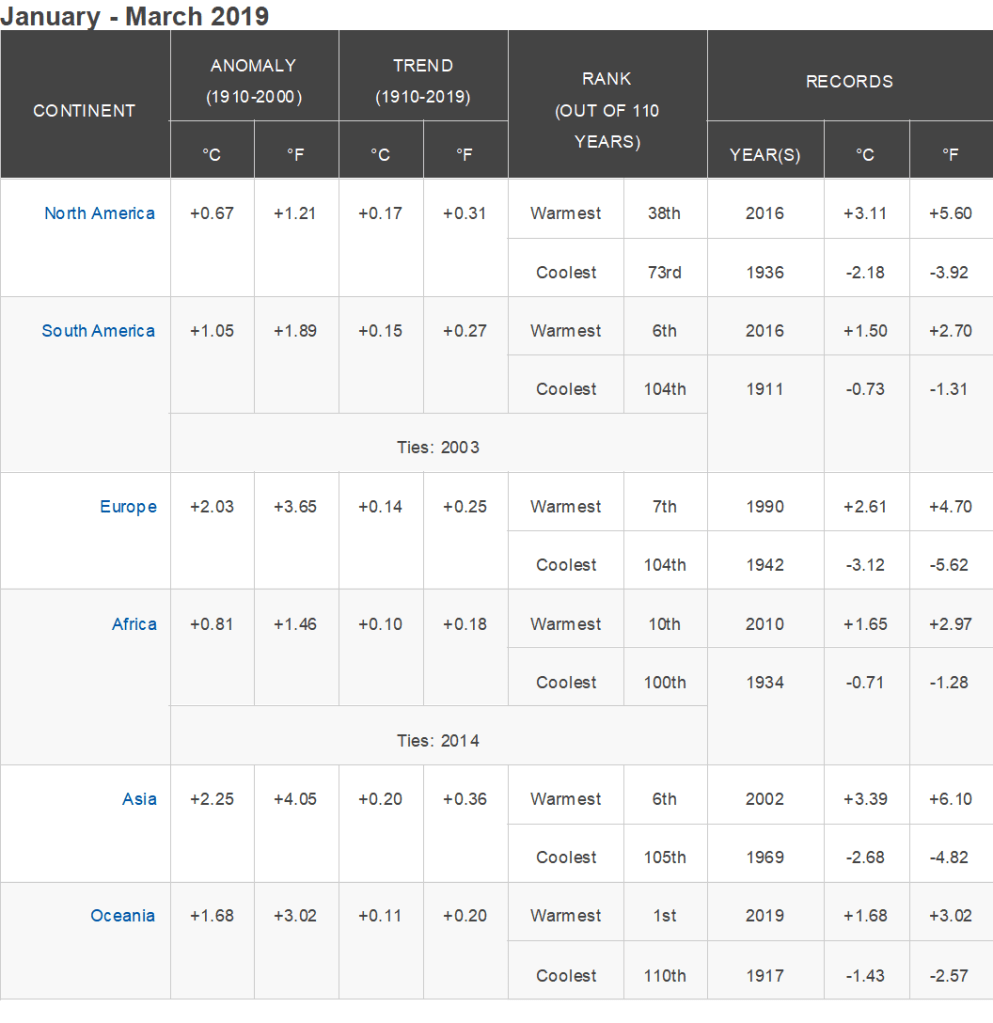

Any warming is good, even this small amount seen in the context of a year in the life of a typical American. Moreover, the details of the statistics reveal that the rise is the result of cold months being warmer, while hotter months have cooled very slightly. False Alarm.

Any warming is good, even this small amount seen in the context of a year in the life of a typical American. Moreover, the details of the statistics reveal that the rise is the result of cold months being warmer, while hotter months have cooled very slightly. False Alarm.