McKitrick: COP28 Worse Threat Than You Think

A demonstration against fossil fuels at the COP28 United Nations climate summit in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. PHOTO BY PETER DEJONG/AP

Ross McKitrick writes at Financial Post: The only thing wrong with the globalist climate agenda — the people won’t have it Excerpts in italics with my bolds and added images.

Phasing out fossil fuels is going to cost way more than ordinary people

will accept. Delegates to COP28 clearly didn’t understand that

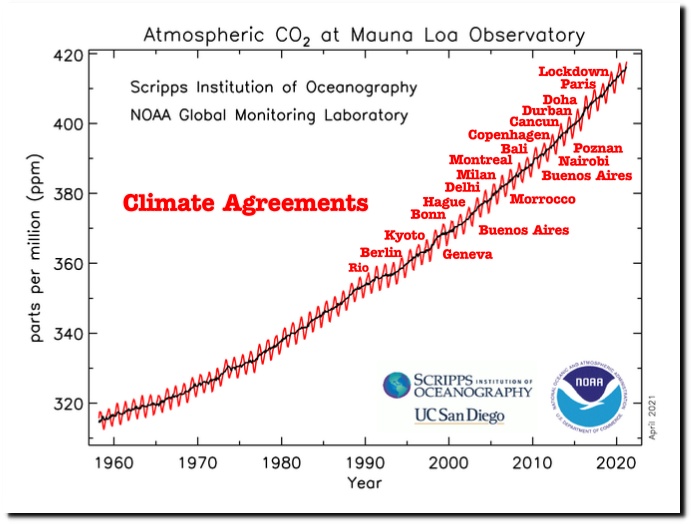

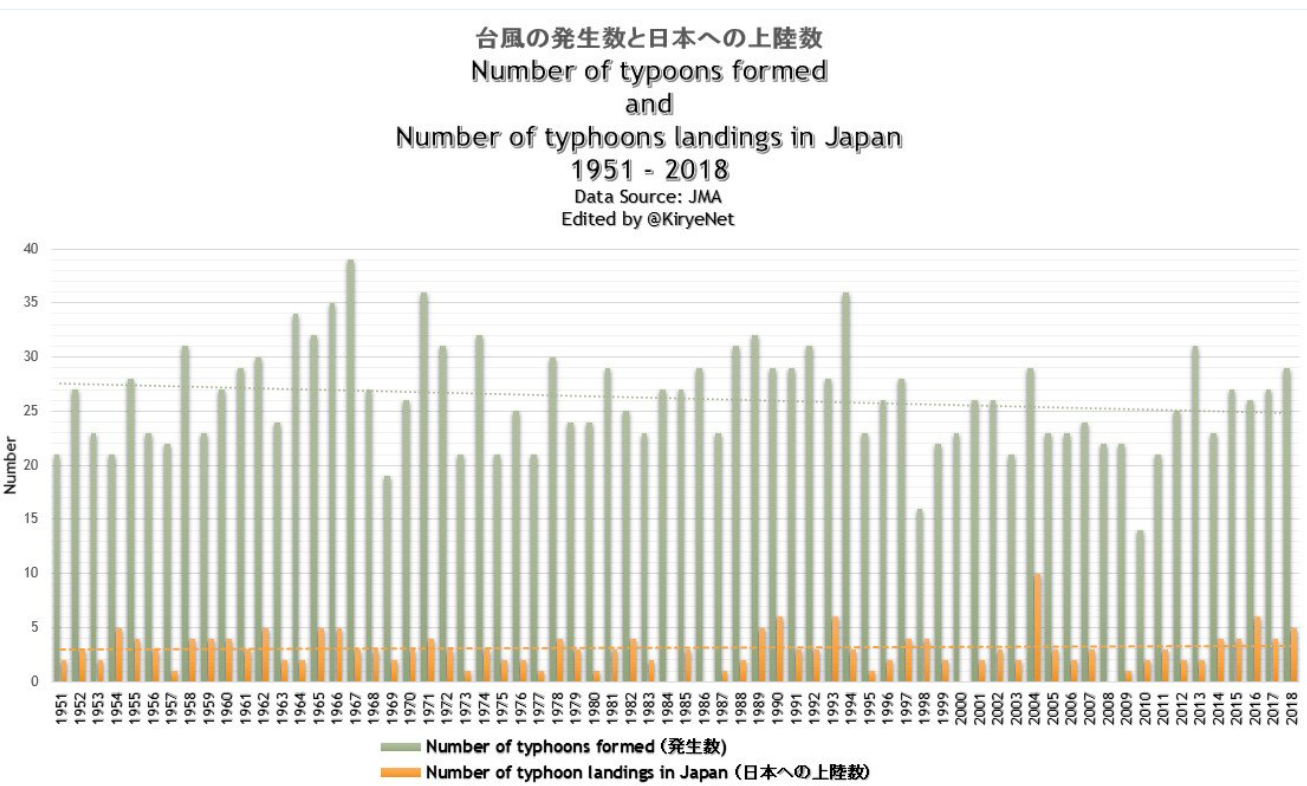

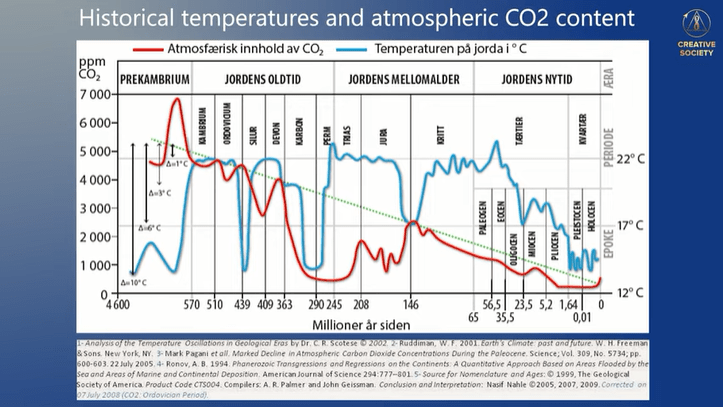

It’s tempting to dismiss the outcome of COP28, the recent United Nations climate change conference in the United Arab Emirates, as mere verbiage, especially the “historic” UAE Consensus about transitioning away from fossil fuels. After all, this is the 28th such conference and the previous ones all pretty much came to nothing. On a chart showing the steady rise in global CO2 emissions since 1950 you cannot spot when the 1997 Kyoto Protocol entered into force (2002), with its supposedly historic language binding developed countries to cap their CO2 emissions at five per cent below 1990 levels by 2012, which they didn’t do. The 2015 Paris Agreement also contained “historic” language that bound countries to further deep emission reductions. Yet the COP28 declaration begins with an admission that the parties are not on track for compliance.

Still, we should not overlook the real meaning of the UAE Consensus.

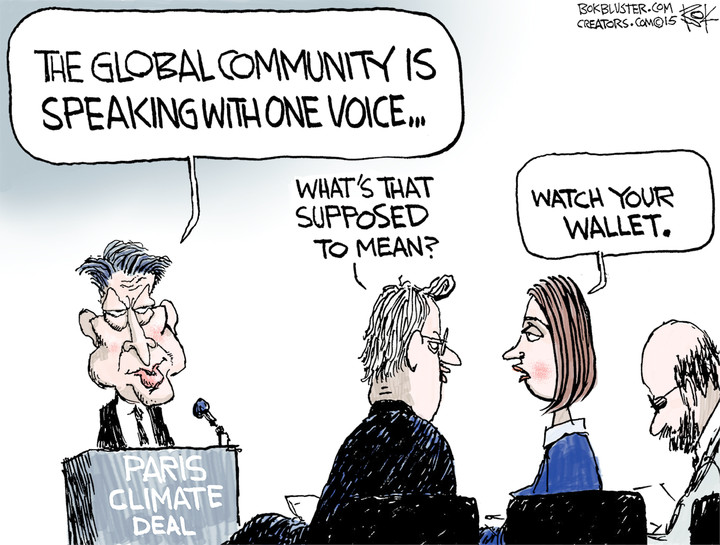

COP agreements used to focus on one thing: targets for reducing greenhouse gases. The UAE Consensus is very different. Across its 196 paragraphs and 10 supplementary declarations it’s a manifesto for global central planning. In their own words, some 90,000 government functionaries aspire to oversee and micromanage agriculture, finance, energy, manufacturing, gender relations, health care, air conditioning, building design and countless other economic and social decisions. It’s all supposedly in the name of fighting climate change, but that’s just the pretext. Take climate away and they’d likely appeal to something else.

Climate change doesn’t necessitate such plans.

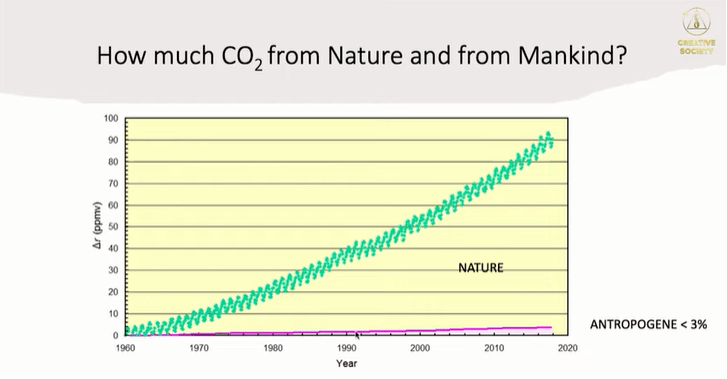

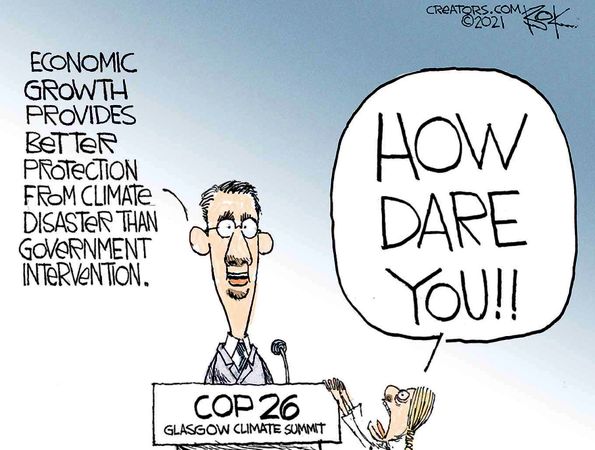

Economists have been studying climate change for many decades and have never considered it grounds to phase out fossil fuels, micromanage society, manage gender relations and so on. Mainstream scientific findings, coupled with mainstream economic analysis, prescribe moderate emission-pricing policies that rely much more on adaptation than mitigation.

The fact that the UAE Consensus is currently non-binding is beside the point. What matters is what the COP28 delegates have said they want to achieve. Two facts stand out: the consensus document announced plans that would cause enormous economic harm if implemented, and it was approved unanimously — yes, by everyone in the room.

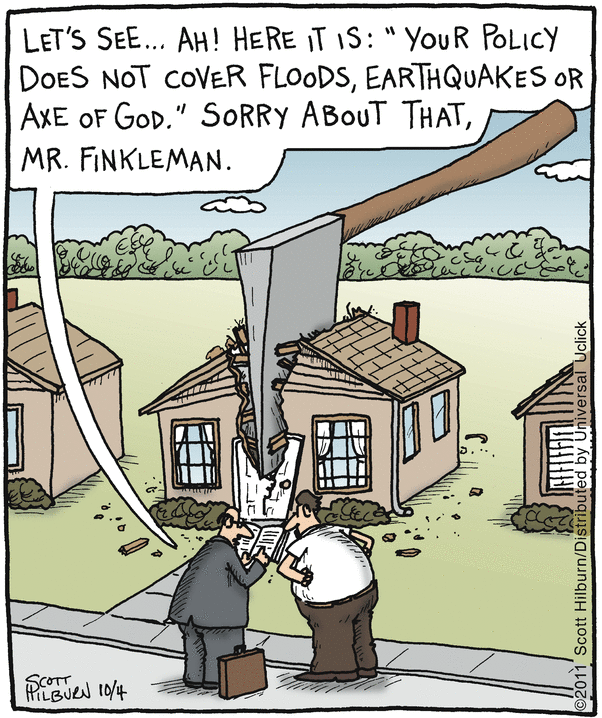

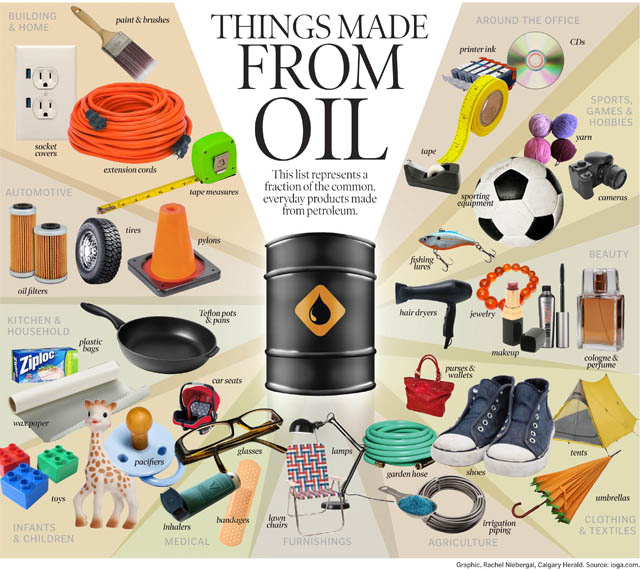

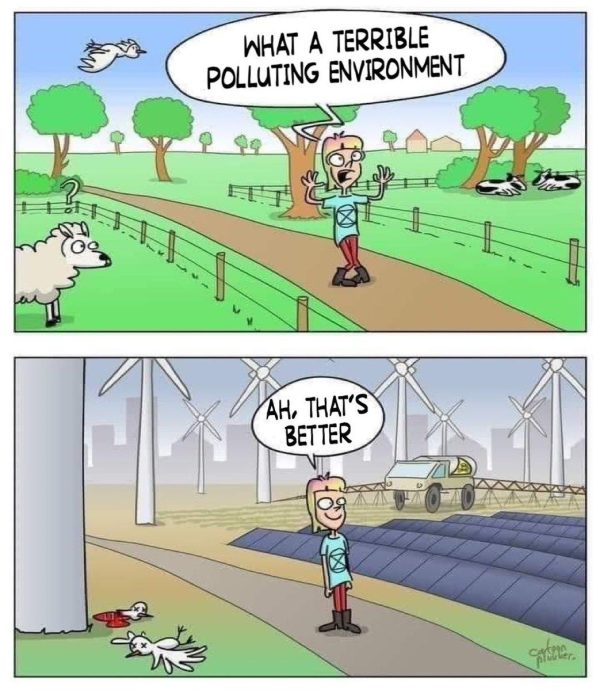

The first point is best illustrated by the language around eliminating fossil fuels. Climate policy is supposed to be about optimally reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. As technology gradually allows emissions to be de-coupled from fuel use, there may eventually be no need to cut back on fuels. But activist delegates insisted on abolitionist language anyway, making elimination of fossil fuels an end in itself. Such fuels are of course essential for our economic standard of living, and 30 years of economic analysis has consistently shown that, even taking account of emissions, phasing out fuels would do humanity far more harm than good. The Consensus statement ignores this, even while claiming to be guided by “the science.”

The second point refers to the fact that all representatives of all governments worldwide endorsed policies that will, if implemented, do extraordinary harm to their own people. Where governments have made even small attempts to take these radical steps, the public has rebelled. This calls into question whom the COP28 delegates actually “represent.” A few elected officials did attend, but no one voted for the great majority of attendees. And have no doubt: even if some heads of state, whether courageous or foolhardy, did go to COP intent on opposing the overall agenda, they would almost certainly be browbeaten into signing the final package.

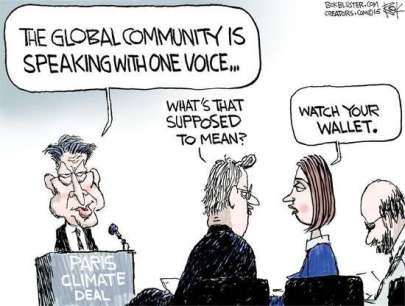

The UAE Consensus is the latest indication that the real fault line in contemporary society is not right versus left, it’s the people versus (for lack of a better word) the globalists. A decade ago this term was only heard on the conspiracy fringe. It has since migrated to the mainstream as the most apt descriptor of a permanent transnational bureaucracy that aspires to run everything, even to the public’s detriment, while insulating themselves from democratic limits.

A hallmark of globalists is their credo of “rules for thee but not for me.” Thousands of delegates fly to Davos or to the year’s COP, many on private jets, to be wined and dined as they advise the rest of us to learn to do without.

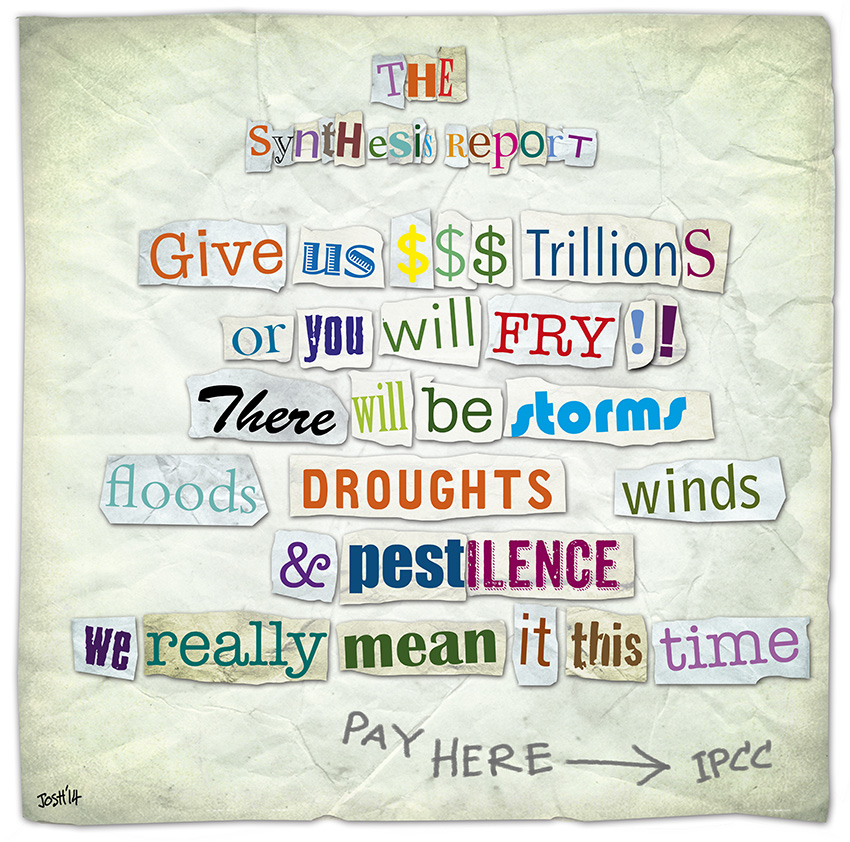

On both COVID-19 and climate change, the same elite has invoked “the science,” not in support of good decision-making, but as a talisman to justify everything they do, including censoring public debate. Complex and uncertain matters are reduced to dogmatic slogans by technocrats who force-feed political leaders a one-sided information stream. Experts outside the process are accorded standing based solely on their obeisance to the preferred narrative, not their knowledge or qualifications. Critics are attacked as purveyors of “misinformation” and “disinformation.” Any opposition to government plans therefore proves the need to suppress free speech.

Eventually, however, the people get the last word. And despite nonstop fear-mongering about an alleged climate crisis, the people tolerate climate policy only insofar as it costs almost nothing.

The climate movement may think that by embedding itself in the globalist elite it can accelerate policy adoption without needing to win elections. In fact, the opposite is happening. Globalists have co-opted the climate issue to try to sell a grotesque central planning agenda that the public has repeatedly rejected. If the UAE Consensus is the future of climate policy, climate policy’s failure is guaranteed.

Then there are billions upon billions of dollars — with Canada and the EU scrambling to match American subsidies — being lavished upon electric battery manufacturers, making “green jobs” a giant tax-funded boondoggle. That the great climate villain in the auto sector, Volkswagen, is a beneficiary of such largesse only makes the absurdity more galling.

Then there are billions upon billions of dollars — with Canada and the EU scrambling to match American subsidies — being lavished upon electric battery manufacturers, making “green jobs” a giant tax-funded boondoggle. That the great climate villain in the auto sector, Volkswagen, is a beneficiary of such largesse only makes the absurdity more galling.