What is Scientific Truth? Previous posts here have discussed the difference between science as a process of discovery (“sciencing” if you will), and science as a catalog of answers to how the world works (“scientism” in this sense). On this issue, I am following Richard Feynman, and also Arthur Eddington, who is quoted at the end.

This post dives into the struggle over truth and science in contemporary society. It also discusses some underlying philosophical confusions leading to distortions of scientific processes and discoveries. Michela Massimi is Professor of Philosophy of Science at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. She works in history and philosophy of science and was the recipient of the 2017 Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Medal by the Royal Society, London, UK. Her article recently published at Aeron is entitled Getting it right. Excerpts in italics with my bolds and images. My takeaway: Science matters only because Truth matters. But do read her entire essay for your own edification. Title is link to essay.

Truth is neither absolute nor timeless. But the pursuit of truth remains at the heart of the scientific endeavour

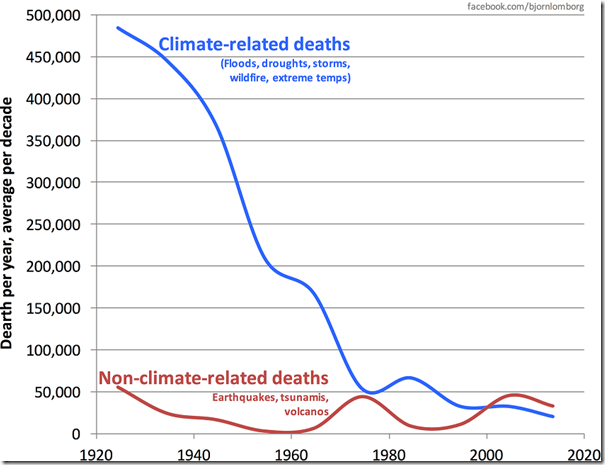

Think of the number of scenarios in which truth matters in science. We care to know whether increased CO2 emission levels cause climate change, and how fast. We care to know whether smoking tobacco increases the risk of lung cancer. We care to know whether poor diet exposes children to the risk of developing obesity, or whether forecasts of economic growth are correct. Truth in science is not esoteric dilly-dallying. It shapes climate science, medicine, public health, the economy and many other worldly endeavours.

That truth matters to science is hardly news. For a long time, people have looked to science for truths about the world. The Scientific Revolution was nothing if not the triumph of Galileo’s scientific truth – hard-won through his telescopic observations – over centuries of dogma about the geocentric system. With its system of epicycles and deferents, Ptolemaic astronomy was at once sophisticated and false. It served to, at best, ‘save the appearances’ about how planets seemed to move in the sky. It did not tell the truth about planetary motion until the discovery of the Copernican explanation. Or consider the Chemical Revolution at the end of the 18th century. We no longer, after all, believe in phlogiston – the fictional imponderable fluid that Georg Ernst Stahl, Joseph Priestley and other natural philosophers at the time believed to be at work in combustion and calcination phenomena. Antoine Lavoisier’s scientific truth about oxygen prevailed over false beliefs about phlogiston.

The main actors of these scientific revolutions often fostered this way of thinking about science as an enquiry leading to the inevitable triumph of truth over past errors. Two centuries after Galileo’s successful defence of the heliocentric system, this idea of the course of scientific truth continued to inspire philosophers. In his Cours de philosophie positive (1830-42), Auguste Comte saw the evolution of human knowledge in three main stages: ‘the Theological, or fictitious; the Metaphysical, or abstract; and the Scientific, or positive’. In the ‘positive’, the third and last stage, ‘an explanation of facts is simply the establishment of a connection between single phenomena and some general facts, the number of which continually diminishes with the progress of science’.

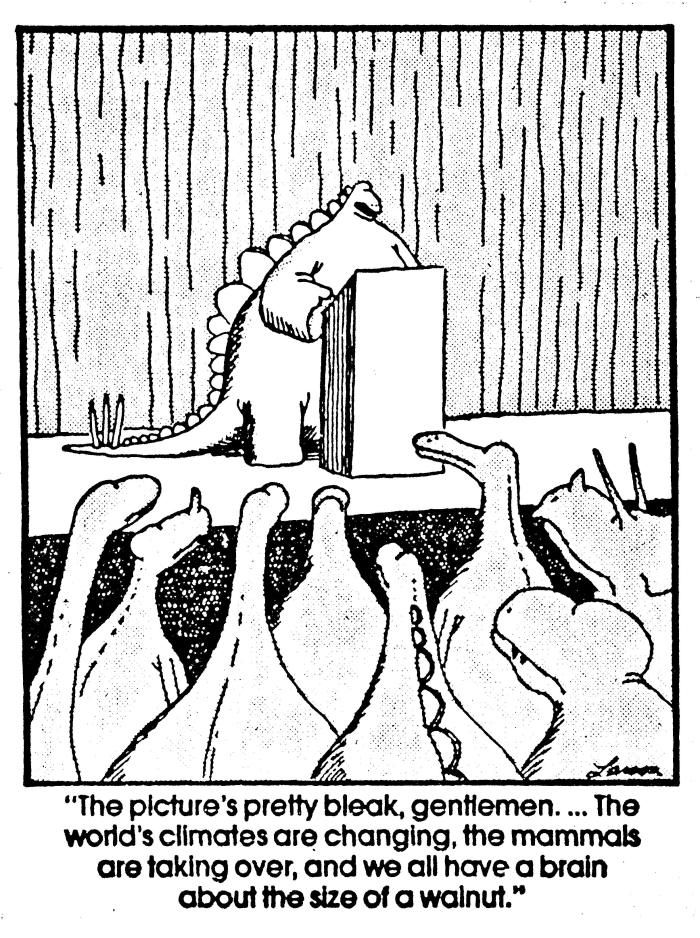

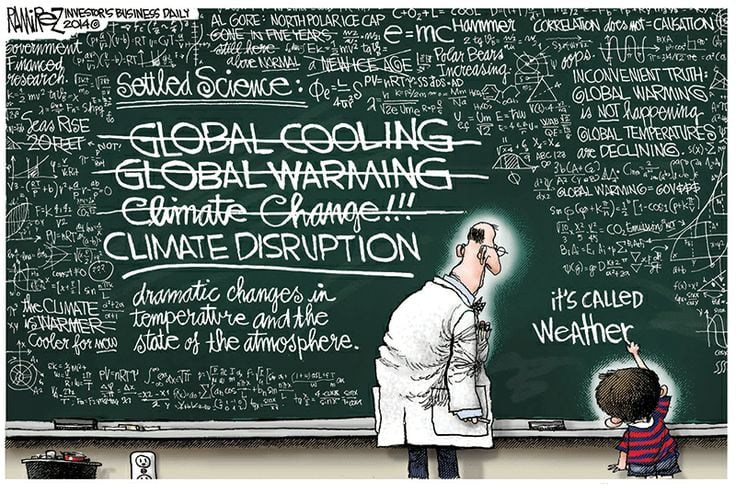

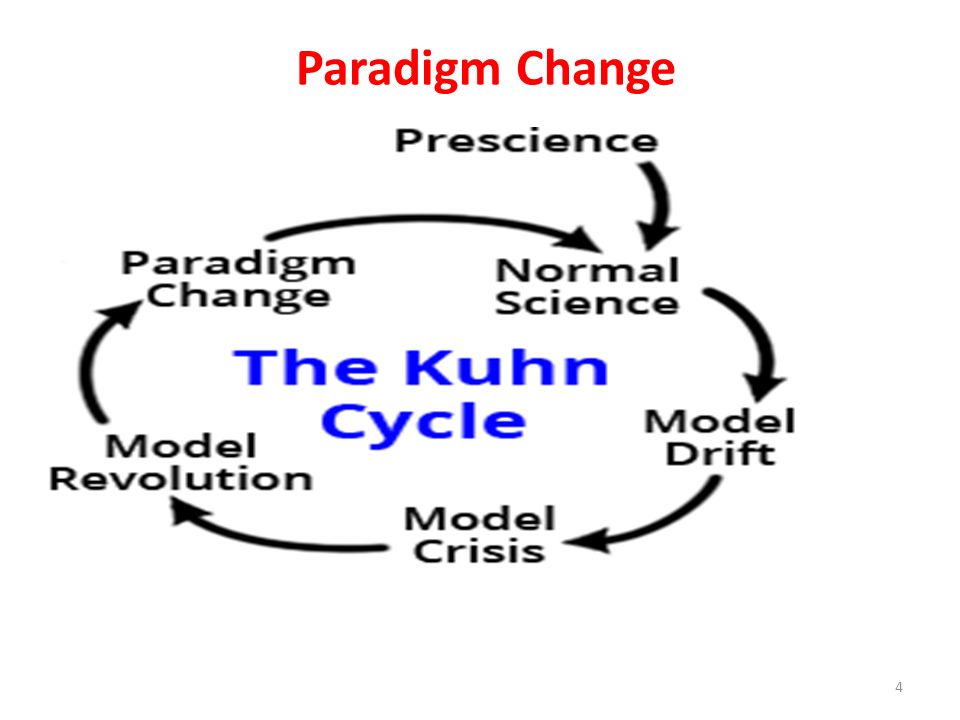

In some scientific quarters, this Comtean notion of how science evolves and progresses remains common currency. But philosophers of science, over the past half-century, have turned against the representation of science as a ceaseless forward march toward truth. It is just not how science works, how it moves through history. It flies in the face of the wonderful and subtle historical nuances of how scientific revolutions have in fact occurred. It does not accommodate how some of the greatest scientific minds held dearly to some false beliefs. It wilfully ignores the many voices, disagreements and controversies through which scientific knowledge has often advanced and progressed over time.

However, many (and legitimate in their own right) criticisms against this naive view of science have committed a similar mistake. They have offered a portrait of science purged of any commitment to truth. They see truth as an inconvenient and disposable feature of science. Fraught as the ideal and pursuit of truth is with tendencies to petty doctrinairism, it is nonetheless a mistake to try to purge it. The fallacy of positivist philosophy was to think of science as coming in stages of some sort, or following a particular path, or historical cycles. The anti-truth trend in the philosophy of science has often ended up repeating this same misstep. It is important to move beyond the sterile dichotomy between the old (quasi-positivist) view of truth in science and the rival anti-truth trend of recent decades.

Let us start with some genuine philosophical questions about truth in science. Here are three: 1) Does science aim at truth? 2) Does science tell us the truth? 3) Should we expect science to tell us the truth?

In each of these questions, ‘science’ is a generic placeholder for whichever scientific discipline we are interested in questioning. Question one might strike us as otiose but, in fact, it triggered one of the liveliest debates of the past 40 years. Bas van Fraassen launched this debate as to whether science aims at truth with his pioneering book The Scientific Image (1980). Does science aim to tell us a true story about nature? Or does it aim only at saving the observable phenomena (namely, providing an account that makes sense of what we can observe, without expecting it to be the true account about nature)?

There are philosophers today who embrace the view that science does not need to be true in order to be good. They argue that asking for truth is risky because it commits one to believing in things (be it epicycles, phlogiston, ether or something else) that might prove false in the future. In their view, ‘empirically adequate’ theories, theories that ‘save the observable phenomena’, are good enough for science. For example, one might take the Standard Model in high-energy physics not as aiming at the truth about whether the world is really carved up into quarks, leptons and force carriers; whether these entities really have the properties that the Standard Model says they have; and so on.

When it comes to the second question – does science tell us the truth? – scientific realists and anti-realists of various stripes have debated it. Leaving aside the aim of science, let us concentrate on its track record instead. Has science told us the truth? Looking at the history of science, does it amount to a persuasive story of truth accumulated over the centuries? Philosophers, historians, sociologists and science-studies scholars have all challenged a simple affirmative answer to this question.

This decades-long, multi-pronged, disenchantment-with-truth trend in philosophy of science starts by rejecting the idea that there are facts about nature that make our scientific claims true or false. Fact-constructivism is only one aspect of this multi-pronged disenchantment-with-truth trend. Outlandish as this might sound, its defenders claim that there is not a single, objective way that the world is; there are rather many different and ‘equally true descriptions of the world, and their truth is the only standard of their faithfulness’, in the words of the philosopher Nelson Goodman. For example, he claimed that we do make facts, but not like, say, a baker makes bread, or a sculptor makes a statue. In Goodman’s view, we make facts any time we construct what he called a ‘version’ of the world (via works of art, of music, of poetry, or of science).

We do this all the time, for example, with stars and constellations. As the philosopher Hilary Putnam expresses it: ‘Nowadays, there is a Big Dipper up there in the sky, and we, so to speak, “put” a Big Dipper up there in the sky by constructing that version.’ Goodman’s world-making view has severe implications for truth in science. ‘Truth,’ he wrote, ‘far from being a solemn and severe master, is a docile and obedient servant. The scientist who supposes that he is single-mindedly dedicated to the search for truth deceives himself … He as much decrees as discovers the laws he sets forth, as much designs as discerns the patterns he delineates.’

Fact-constructivism sounds too radical to many philosophers, and alienating to most scientists. So here is another approach against factual truth, well-known among philosophers of science. Over the past 40 years, they have produced an extraordinary amount of work on models in science. The role of abstractions and idealisations in scientific models, they maintain, is to select and to distort aspects of the relevant target system. The billiard-ball model of Brownian motion, for example, represents the motion of molecules by idealising them as perfectly spherical billiard balls. Moreover, the model abstracts, or removes, molecules from their actual environment, which is of course where collisions among molecules take place.

Studying modelling practices in science has led some to argue that science does not tell the truth but it does provide important non-factive understanding. Consider, for instance, Boyle’s gas law, which captures the relation between pressure p and volume v in an ideal gas at constant temperature. At best, Boyle’s law is true ceteris paribus (ie, all else being equal) in highly idealised and contrived circumstances. There simply is no ideal gas with perfectly spherical molecules displaying ‘atomic facts’ (in a quasi-Wittgensteinian sense) that make Boyle’s law true. Despite being true of nothing real, the billiard-ball model of Brownian motion and Boyle’s ideal gas law do nonetheless provide important non-factual understanding of the behaviour of real gases. For they allow scientists to understand the relation between decreasing volume and increasing pressure in any gas, even if there are no atomic facts in nature about perfectly spherical molecules corresponding to such idealisations.

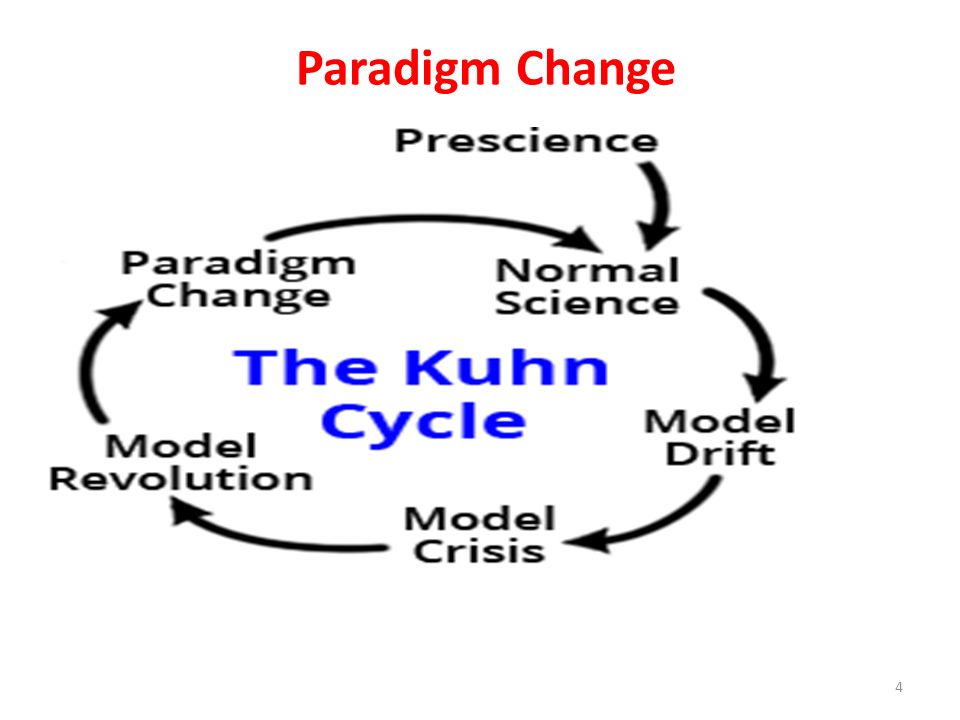

Anti-dogmatic and anti-monist approaches to science have also questioned the value, as well as the facticity, of truth. From the 1960s, science-studies scholars began to see the word ‘truth’ as evoking unpalatable petty doctrinairism and intracultural battles in the wake of the Vietnamese war, postmodernism and, later on, what became known as the ‘science wars’. Many saw the physicist Thomas Kuhn as the forefather of a new historicist trend that dismantled what they perceived as the naive view that science aims at or tracks truth. Kuhn saw himself as ‘a fact lover and a truth seeker’. Yet in the final remarks to his classic The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), he made a prescient, almost ominous, warning:

Does it really help to imagine that there is some one full, objective, true account of nature and that the proper measure of scientific achievement is the extent to which it brings us closer to the ultimate goal? … Successive stages in that developmental process are marked by an increase in articulation and specialisation. And the entire process might have occurred, as we now suppose biological evolution did, without benefit of a set goal, a permanent fixed scientific truth, of which each stage in the development of scientific knowledge is a better exemplar.

For Kuhn, truth is not an overarching aim of science across scientific revolutions. Nor do scientific revolutions (eg, from Ptolemaic to Copernican astronomy) track truth either. What they do, at best, is to increase our ability to solve anomalies that beset the previous paradigm (as when we eventually discovered that retrograde motion was only an illusion, and not something that needed epicycles and deferents to be explained).

We see the spirit of Kuhn’s warning in discussions today. Truth itself is not enough to settle or even guide debates about expertise, trust, consensus and dissent in science. The philosophers of science Inmaculada de Melo-Martín and Kristen Intemann have described the matter well in their book The Fight Against Doubt (2018). When it comes to the role of science in policymaking, the key is ‘engaging in discussions with all relevant parties about the values at stake, rather than the truth of particular scientific claims’. Policymaking involves politics and values, and ‘disagreement about values cannot, and should not, be decided by scientists alone’ or by just scientific evidence.

We see the spirit of Kuhn’s warning in discussions today. Truth itself is not enough to settle or even guide debates about expertise, trust, consensus and dissent in science. The philosophers of science Inmaculada de Melo-Martín and Kristen Intemann have described the matter well in their book The Fight Against Doubt (2018). When it comes to the role of science in policymaking, the key is ‘engaging in discussions with all relevant parties about the values at stake, rather than the truth of particular scientific claims’. Policymaking involves politics and values, and ‘disagreement about values cannot, and should not, be decided by scientists alone’ or by just scientific evidence.

The third question is whether we should expect science to tell us the truth, or is truth (or at least the notion of factual truth) not best left to logicians and metaphysicians?

While critical analyses of factual truth are indeed best left to logicians and metaphysicians, philosophers of science should not abdicate their responsibility to talk about truth in science. The quasi-Wittgensteinian myth of atomic facts as the truth-makers of scientific claims has proved inadequate to even scratch the surface of very complex practices in science. But that is not a good reason (or pretext) for forgoing truth altogether. Nor is it a reason for concluding that science should not be expected to tell us the truth.

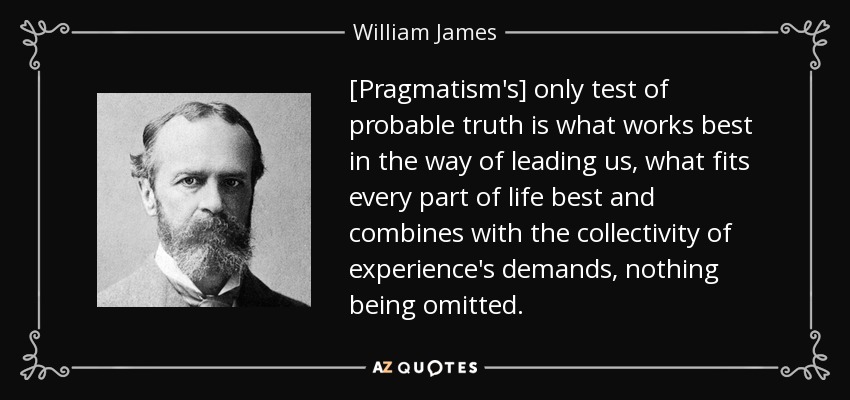

But whose truth? By whose lights? Some might be tempted at this point by a Jamesian pragmatist theory of truth. American pragmatism has traditionally provided an alternative way of thinking about truth, which some philosophers of science see as more congenial to capturing the complex nuances and the power structure of scientific practice.

In James’s words: ‘“The true” … is only the expedient in the way of our thinking, just as “the right” is only the expedient in the way of our behaving.’ Stripped of its rhetorical flourishes, for James to be true is (to a good approximation) to work successfully. A scientific model is true – on a loosely Jamesian view – if it successfully facilitates and enables activities (be they epistemic or not). If the billiard-ball model of Brownian motion helps scientists to predict the behaviour of gas molecules, for example, the model is (pragmatically) true. The falseness of the presumption of perfectly spherical molecules does not matter.

The risk with a James-inspired conception of truth, as I see it, is that it is too malleable to resist the tides of time and the stresses of social forces endlessly at work in science. A James-inspired view of truth abdicates the expectation that science tells us the truth in the name of a non-better-qualified kind of success of a scientific practice. But how to tell apart cases where success does indeed track truth from cases where it does not? More to the point, when it comes to matters such as climate change, the benefit of vaccinating children, or economic forecasts, we seem to need more than a malleable Jamesian conception of truth for the sake of scientifically informed decisions that do not bow to pressure from powerful lobbies and political agendas (in the name of what ‘might work’). But, someone might reply, how can truth and pluralism go hand in hand if not by opting for a Jamesian conception of truth (if we really care about truth at all)?

There is another way of thinking about how truth and pluralism might go hand in hand, without reducing matters of truth to calculations of what is pragmatically good to individuals or communities sharing a scientific perspective at some point in time. First, it is necessary to understand the key term ‘scientific perspective’ and how it impinges on scientific pluralism. In its original use by the philosopher Ronald Giere in 2006, ‘scientific perspective’ is akin to Kuhn’s disciplinary matrix: a set of scientific models (including the relevant experimental instruments to gather data). In broader terms, scientific perspective is the disciplinary practice of a real scientific community at any given historical time. It includes the knowledge they produce, and the theoretical, technological and experimental resources they use, or that guide their work.

The time for a defence of truth in science has come. It begins with a commitment to get things right, which is at the heart of the realist programme, despite mounting Kuhnian challenges from the history of science, considerations about modelling, and values in contemporary scientific practice. In the simple-minded sense, getting things right means that things are as the relevant scientific theory says that they are. Climate science is true if what it says about CO2 emissions (and their effects on climate change) corresponds to the way that things are in nature. For the sake of powerful economic interests, sociopolitical consequences or simply different economic principles, one can try to discount, mitigate, compensate for, disregard or ignore altogether the way that things are. But doing so is to forgo the normative nature of the realist commitment in science. The scientific world, we have seen, is too complex and messy to be represented by any quasi-Wittgensteinian picture of atomic facts. Nor can the naive image of Comte’s positive science render justice to it. But acknowledging complexity and historical nuances gives no reason (or justification) for forgoing truth altogether; much less for concluding that science trades in falsehoods of some kind. It is part of our social responsibility as philosophers of science to set the record straight on such matters.

We should expect science to tell us the truth because, by realist lights, this is what science ought to do. Truth – understood as getting things right – is not the aim of science, because it is not what science (or, better, scientists) should aspire to (assuming one has realist leanings). Instead, it is what science ought to do by realist lights. Thus, to judge a scientific theory or model as true is to judge it as one that ‘commands our assent’. Truth, ultimately, is not an aspiration; a desirable (but maybe unachievable) goal; a figment in the mind of the working scientist; or, worse, an insupportable and dispensable burden in scientific research. Truth is a normative commitment inherent in scientific knowledge.

Constructive empiricists, instrumentalists, Jamesian pragmatists, relativists and constructivists do not share the same commitment. They do not share with the realist a suitable notion of ‘rightness’. As an example, compare the normative commitment to get things right with the view of the philosopher Richard Rorty, in whose hands Putnam’s truth as ‘idealised warranted assertibility’ reduces to what is acceptable to ‘us as we should like to be … us educated, sophisticated, tolerant, wet liberals, the people who are always willing to hear the other side, to think out all the implications’.

Getting things right is not a norm about us at our best, ‘educated, sophisticated, tolerant, wet liberals’. It is a norm inherent in scientific knowledge. To claim to know something in science (or about a scientific topic or domain) is to claim for the truth of the relevant beliefs about that topic or domain.

Getting things right is not a norm about us at our best, ‘educated, sophisticated, tolerant, wet liberals’. It is a norm inherent in scientific knowledge. To claim to know something in science (or about a scientific topic or domain) is to claim for the truth of the relevant beliefs about that topic or domain.

Thinking of truth as a normative commitment inherent in the very notion of scientific knowledge brings some benefits. It overcomes a false dichotomy between atomic facts and non-factive, non-truth-conducive inferences. And it makes realism compatible with perspectivism. Scientific communities that endorse historically and culturally situated scientific perspectives (either across the history of science or in contemporary science, across different fields or different scientific programmes) share (and indeed ought to) a normative commitment to get things right. That is a minimum requirement to pass the bar of what we count as ‘scientific knowledge’.

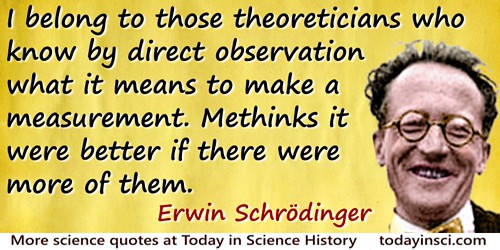

Getting the evidence right, in the first instance – via accurate measurements, sound non-ad-hoc procedures, and robust inferential strategies – defines any research programme that is worth being called ‘scientific’. The realist commitment to get things right must begin with getting the evidence right. No perspective worthy of being called ‘scientific’ survives fudging the evidence, massaging or altering the data or discarding evidence.

Scientists ought to share rules for cross-perspectival assessment. That our knowledge is situated and perspectival does not make scientific truths relativised to perspectives. Often enough, scientific perspectives themselves provide the rules for cross-perspectival assessment. Those rules can be as simple as translating the 10 degree Celsius temperature in Edinburgh today into the 50 degree equivalent on the Fahrenheit scale. Or they can be as complex as retrieving the viscosity of a fluid in statistical mechanics, where fluids are treated as statistical ensembles of a large number of discrete molecules.

Let there be no doubt: scientific knowledge is the product of our getting it right across our perspectival multicultural scientific history. Scientific knowledge is not a prerogative of our Western cultural perspective (and its discipline-specific scientific perspectives) but the outcome of a plurality of historically and culturally situated scientific perspectives that, over millennia, have reliably produced knowledge with the tools, resources and concepts respectively available to each and every one of them.

Scientific truths are the resilient and robust outcome of a plurality of scientific perspectives that, over time, have meshed with one another in their (tacit, implicit and often survival-adaptive) normative commitment to reliably produce scientific knowledge for us as humankind. That is why, far from being an insufferable hindrance to scientific pluralism, truth is in fact its best safeguard in tolerant, open and democratic societies that are genuinely committed to the advancement of scientific knowledge in the very many faces it comes with.

Footnote:

Religious creeds are a great obstacle to any full sympathy between the outlook of the scientist and the outlook which religion is so often supposed to require … The spirit of seeking which animates us refuses to regard any kind of creed as its goal. It would be a shock to come across a university where it was the practice of the students to recite adherence to Newton’s laws of motion, to Maxwell’s equations and to the electromagnetic theory of light. We should not deplore it the less if our own pet theory happened to be included, or if the list were brought up to date every few years. We should say that the students cannot possibly realise the intention of scientific training if they are taught to look on these results as things to be recited and subscribed to. Science may fall short of its ideal, and although the peril scarcely takes this extreme form, it is not always easy, particularly in popular science, to maintain our stand against creed and dogma.

― Arthur Stanley Eddington

See Also:

Data, Facts and Information

Three Wise Men Talking Climate

Head, Heart and Science

Post-Truth Climatism

How Science Is Losing Its Humanity

It’s not what happens in class that matters. The university has long been corrupted by athletics, politicization of the curriculum, identity politics, grade inflation, affirmative action, the death of the humanities, and ideological bias among faculty. What matters is the chit you receive at graduation.

It’s not what happens in class that matters. The university has long been corrupted by athletics, politicization of the curriculum, identity politics, grade inflation, affirmative action, the death of the humanities, and ideological bias among faculty. What matters is the chit you receive at graduation.

We see the spirit of Kuhn’s warning in discussions today. Truth itself is not enough to settle or even guide debates about expertise, trust, consensus and dissent in science. The philosophers of science Inmaculada de Melo-Martín and Kristen Intemann have described the matter well in their book The Fight Against Doubt (2018). When it comes to the role of science in policymaking, the key is ‘engaging in discussions with all relevant parties about the values at stake, rather than the truth of particular scientific claims’. Policymaking involves politics and values, and ‘disagreement about values cannot, and should not, be decided by scientists alone’ or by just scientific evidence.

We see the spirit of Kuhn’s warning in discussions today. Truth itself is not enough to settle or even guide debates about expertise, trust, consensus and dissent in science. The philosophers of science Inmaculada de Melo-Martín and Kristen Intemann have described the matter well in their book The Fight Against Doubt (2018). When it comes to the role of science in policymaking, the key is ‘engaging in discussions with all relevant parties about the values at stake, rather than the truth of particular scientific claims’. Policymaking involves politics and values, and ‘disagreement about values cannot, and should not, be decided by scientists alone’ or by just scientific evidence.

Getting things right is not a norm about us at our best, ‘educated, sophisticated, tolerant, wet liberals’. It is a norm inherent in scientific knowledge. To claim to know something in science (or about a scientific topic or domain) is to claim for the truth of the relevant beliefs about that topic or domain.

Getting things right is not a norm about us at our best, ‘educated, sophisticated, tolerant, wet liberals’. It is a norm inherent in scientific knowledge. To claim to know something in science (or about a scientific topic or domain) is to claim for the truth of the relevant beliefs about that topic or domain.