Head, Heart and Science Updated

A man who has not been a socialist before 25 has no heart. If he remains one after 25 he has no head.—King Oscar II of Sweden

H/T to American Elephants for linking to this Jordan Peterson video: The Fatal Flaw in Leftist Thought. He has an outstanding balance between head and heart, and also applies scientific analysis to issues, in this case the problem of identity politics and leftist ideology.

As usual Peterson makes many persuasive points in this talk. I was struck by his point that we have established the boundary of extremism on the right, but no such boundary exists on the left. Our society rejects right wingers who cross the line and assert racial superiority. Conservative voices condemn that position along with the rest.

We know from the Soviet excesses that the left can go too far, but what is the marker? Left wingers have the responsibility to set the boundary and sanction the extremists. Peterson suggests that the fatal flaw is the attempt to ensure equality of outcomes for identity groups, and explains why that campaign is impossible.

From Previous Post on Head, Heart and Science

Recently I had an interchange with a friend from high school days, and he got quite upset with this video by Richard Lindzen. So much so, that he looked up attack pieces in order to dismiss Lindzen as a source. This experience impressed some things upon me.

Climate Change is Now Mostly a Political Football (at least in USA)

My friend attributed his ill humor to the current political environment. He readily bought into slanderous claims, and references to being bought and paid for by the Koch brothers. At this point, Bernie and Hilliary only disagree about who is the truest believer in Global Warming. Once we get into the general election process, “Fighting Climate Change” will intensify as a wedge issue, wielded by smug righteous believers on the left against the anti-science neanderthals on the right.

So it is a hot label for social-media driven types to identify who is in the tribe (who can be trusted) and the others who can not. For many, it is not any deeper than that.

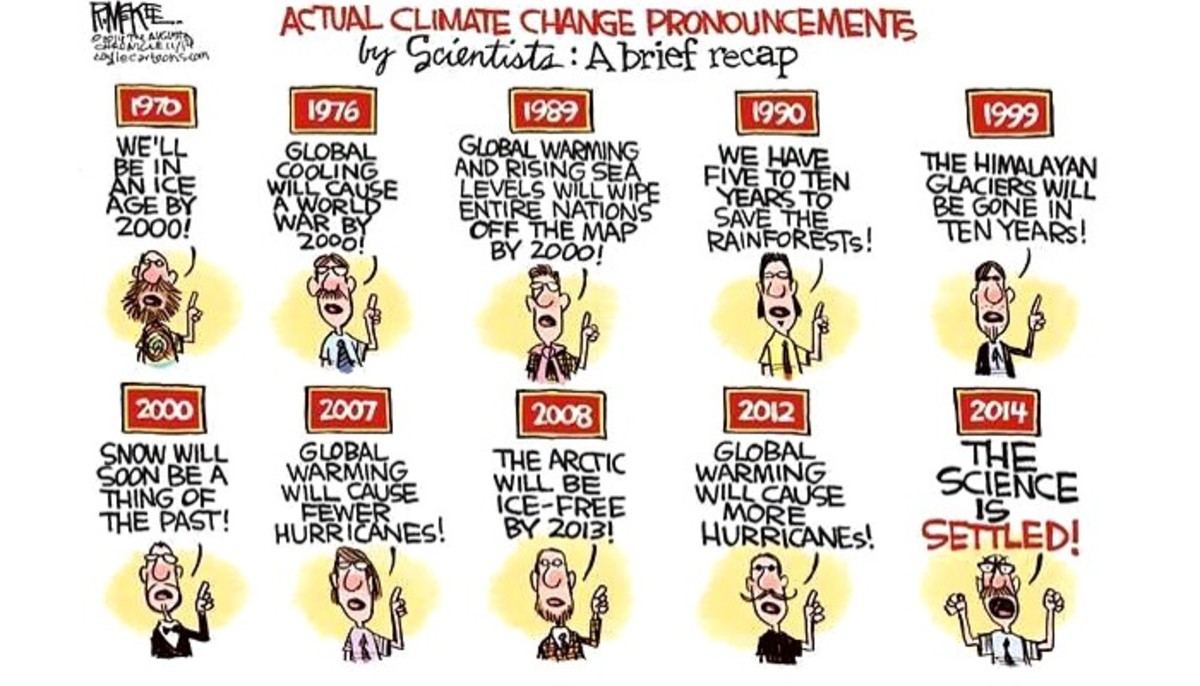

The Warming Consensus is a Timesaver

My friend acknowledged that his mind was made up on the issue because 95+% of scientists agreed. It was extremely important for him to discredit Lindzen as untrustworthy to maintain the unanimity. When a Warmist uses: “The Scientists say: ______” , it is much the same as a Christian reference: “The Bible says: _______.” In both cases, you can fill in the blank with whatever you like, and attribute your idea to the Authority. And most importantly, you can keep the issue safely parked in a No Thinking Zone. There are plenty of confusing things going on around us, and no one wants one more ambiguity requiring time and energy.

Science Could Lose the Delicate Balance Between Head and Heart

Decades ago Arthur Eddington wrote about the tension between attitudes of artists and scientists in their regarding nature. On the one hand are people filled with the human impulse to respect, adore and celebrate the beauty of life and the world. On the other are people driven by the equally human need to analyze, understand and know what to expect from the world. These are Yin and Yang, not mutually exclusive, and all of us have some of each.

Most of us can recall the visceral response in the high school biology lab when assigned to dissect a frog. Later on, crayfish were preferred (less disturbing to artistic sensibilities). For all I know, recent generations have been spared this right of passage, to their detriment. For in the conflict between appreciating things as they are, and the need to know why and how they are, we are exposed to deeper reaches of the human experience. If you have ever witnessed, as I have, a human body laid open on an autopsy table, then you know what I mean.

Anyone, scientist or artist, can find awe in contemplating the mysteries of life. There was a time when it was feared that the march of science was so advancing the boundaries of knowledge that the shrinking domain of the unexplained left ever less room for God and religion. Practicing scientists knew better. Knowing more leads to discovering more unknowns; answers produce cascades of new questions. The mystery abounds, and the discovery continues. Eddington:

It is pertinent to remember that the concept of substance has disappeared from fundamental physics; what we ultimately come down to is form. Waves! Waves!! Waves!!! Or for a change — if we turn to relativity theory — curvature! Energy which, since it is conserved, might be looked upon as the modern successor of substance, is in relativity theory a curvature of space-time, and in quantum theory a periodicity of waves. I do not suggest that either the curvature or the waves are to be taken in a literal objective sense; but the two great theories, in their efforts to reduce what is known about energy to a comprehensible picture, both find what they require in a conception of “form”.

What do we really observe? Relativity theory has returned one answer — we only observe relations. Quantum theory returns another answer — we only observe probabilities.

It is impossible to trap modern physics into predicting anything with perfect determinism because it deals with probabilities from the outset.

― Arthur Stanley Eddington

Works by Eddington on Science and the Natural World are here.

Summary

The science problem today is not the scientists themselves, but with those attempting to halt its progress for the sake of political power and wealth.

Eddington:

Religious creeds are a great obstacle to any full sympathy between the outlook of the scientist and the outlook which religion is so often supposed to require … The spirit of seeking which animates us refuses to regard any kind of creed as its goal. It would be a shock to come across a university where it was the practice of the students to recite adherence to Newton’s laws of motion, to Maxwell’s equations and to the electromagnetic theory of light. We should not deplore it the less if our own pet theory happened to be included, or if the list were brought up to date every few years. We should say that the students cannot possibly realise the intention of scientific training if they are taught to look on these results as things to be recited and subscribed to. Science may fall short of its ideal, and although the peril scarcely takes this extreme form, it is not always easy, particularly in popular science, to maintain our stand against creed and dogma.

― Arthur Stanley Eddington

But enough about science. It’s politicians we need to worry about:

Footnote:

“Asked in 1919 whether it was true that only three people in the world understood the theory of general relativity, [Eddington] allegedly replied: ‘Who’s the third?”

Postscript: For more on how we got here see Warmists and Rococo Marxists.