UAH July 2024: Little Warming from “Hot” July

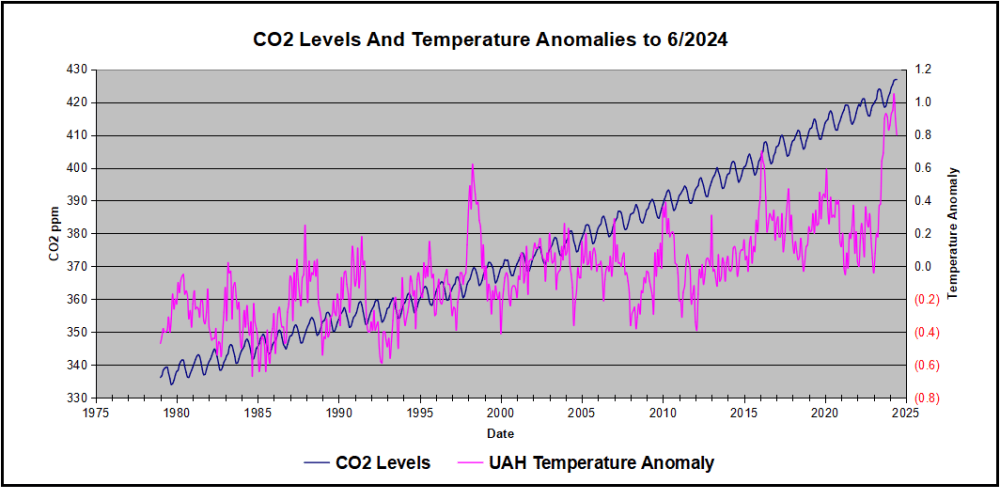

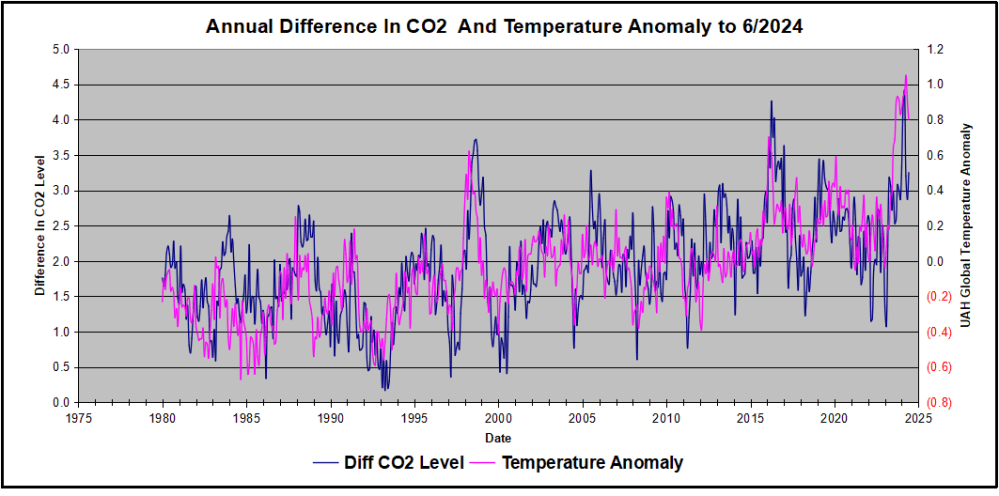

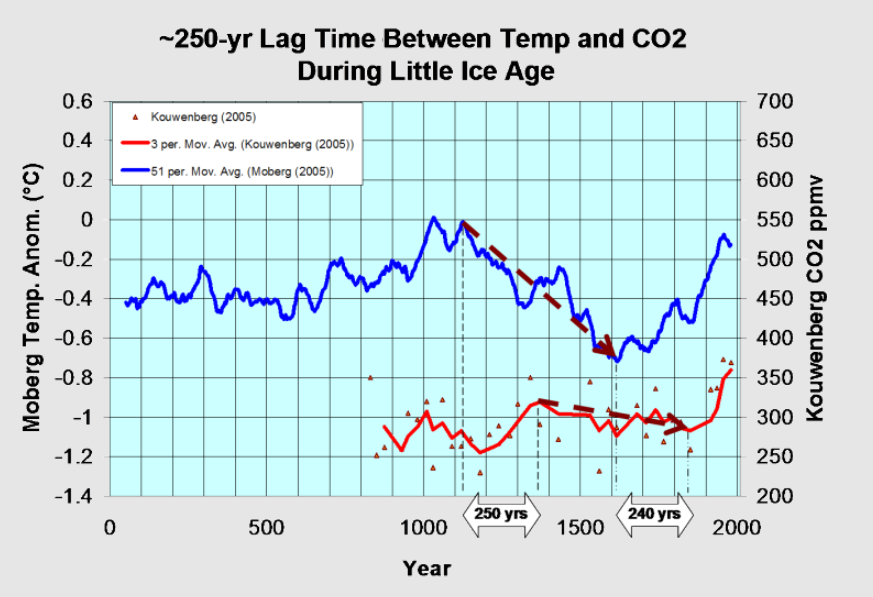

The post below updates the UAH record of air temperatures over land and ocean. Each month and year exposes again the growing disconnect between the real world and the Zero Carbon zealots. It is as though the anti-hydrocarbon band wagon hopes to drown out the data contradicting their justification for the Great Energy Transition. Yes, there has been warming from an El Nino buildup coincidental with North Atlantic warming, but no basis to blame it on CO2.

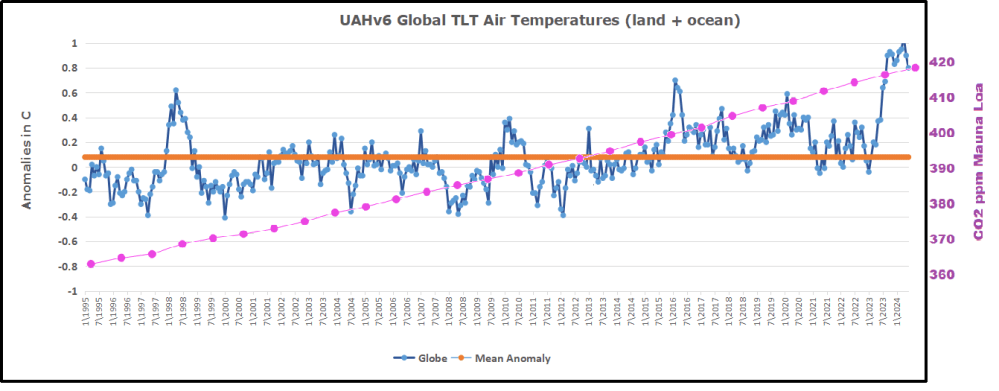

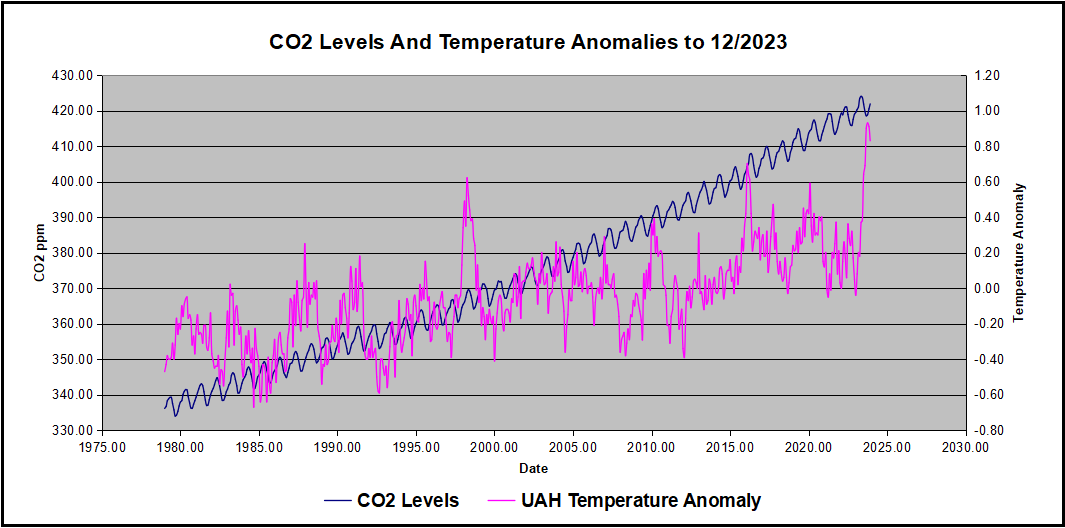

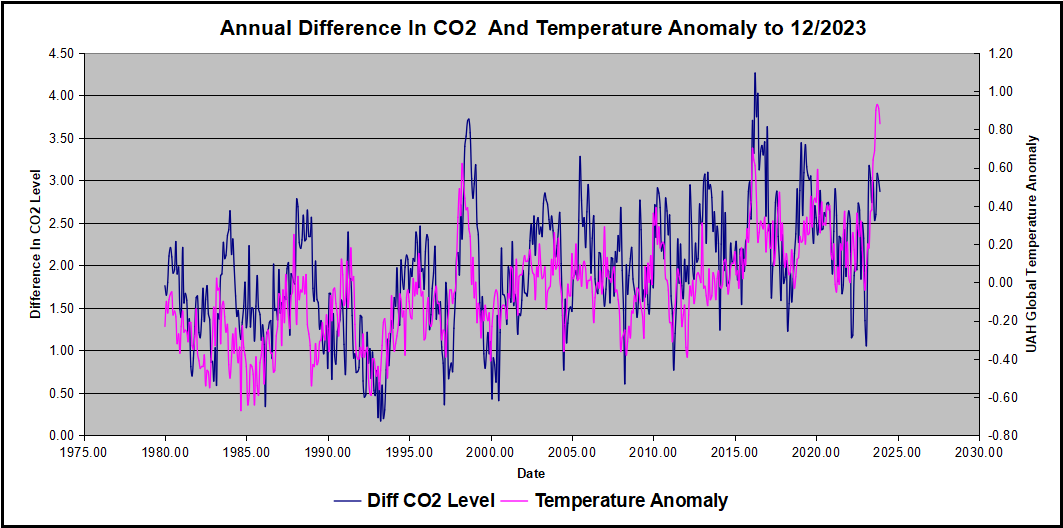

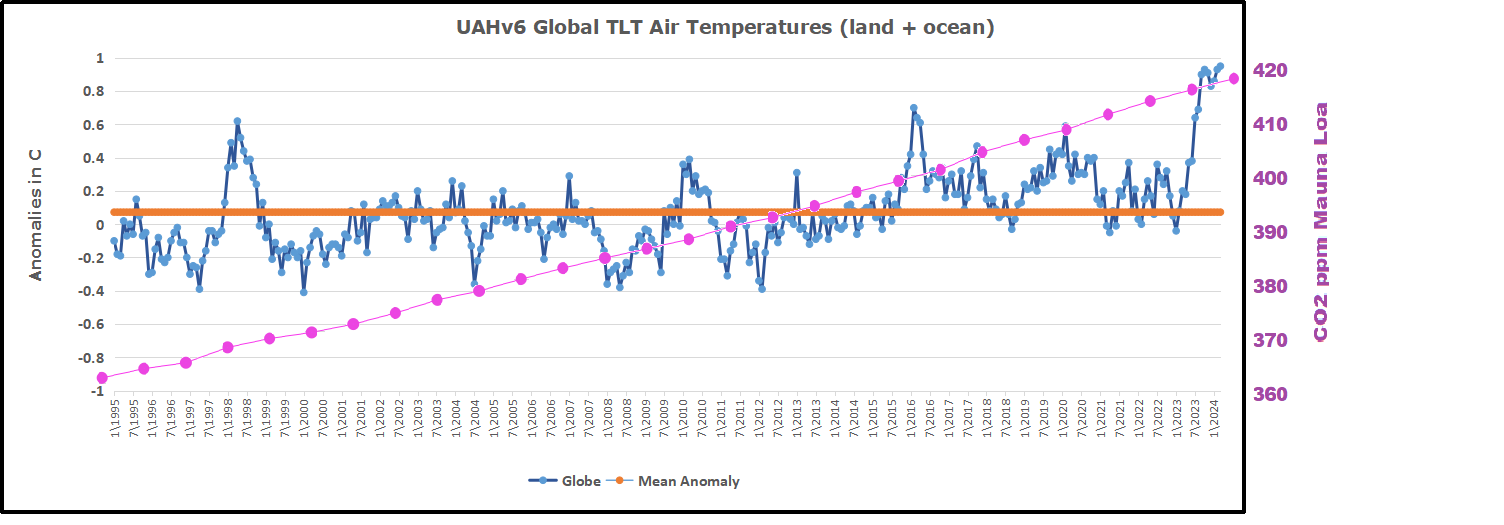

As an overview consider how recent rapid cooling completely overcame the warming from the last 3 El Ninos (1998, 2010 and 2016). The UAH record shows that the effects of the last one were gone as of April 2021, again in November 2021, and in February and June 2022 At year end 2022 and continuing into 2023 global temp anomaly matched or went lower than average since 1995, an ENSO neutral year. (UAH baseline is now 1991-2020). Now we have an usual El Nino warming spike of uncertain cause, but unrelated to steadily rising CO2.

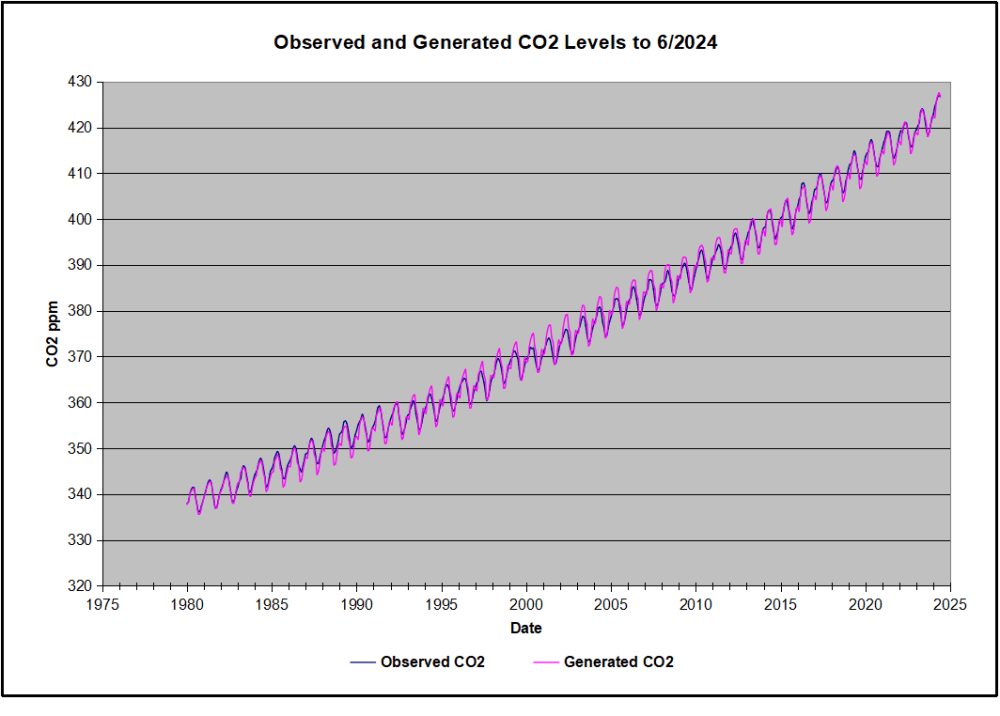

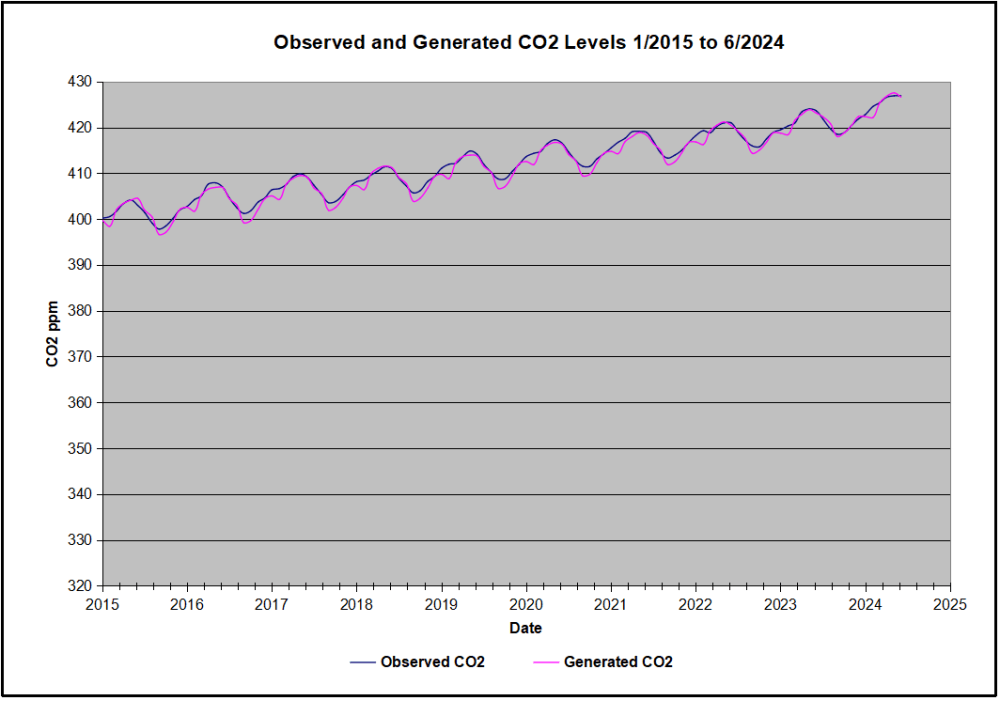

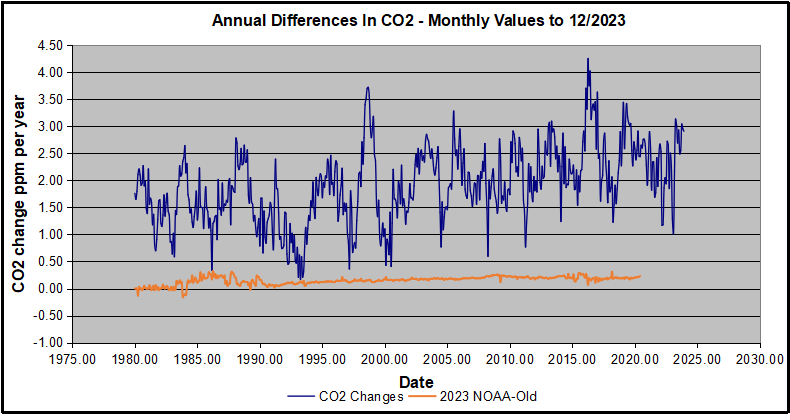

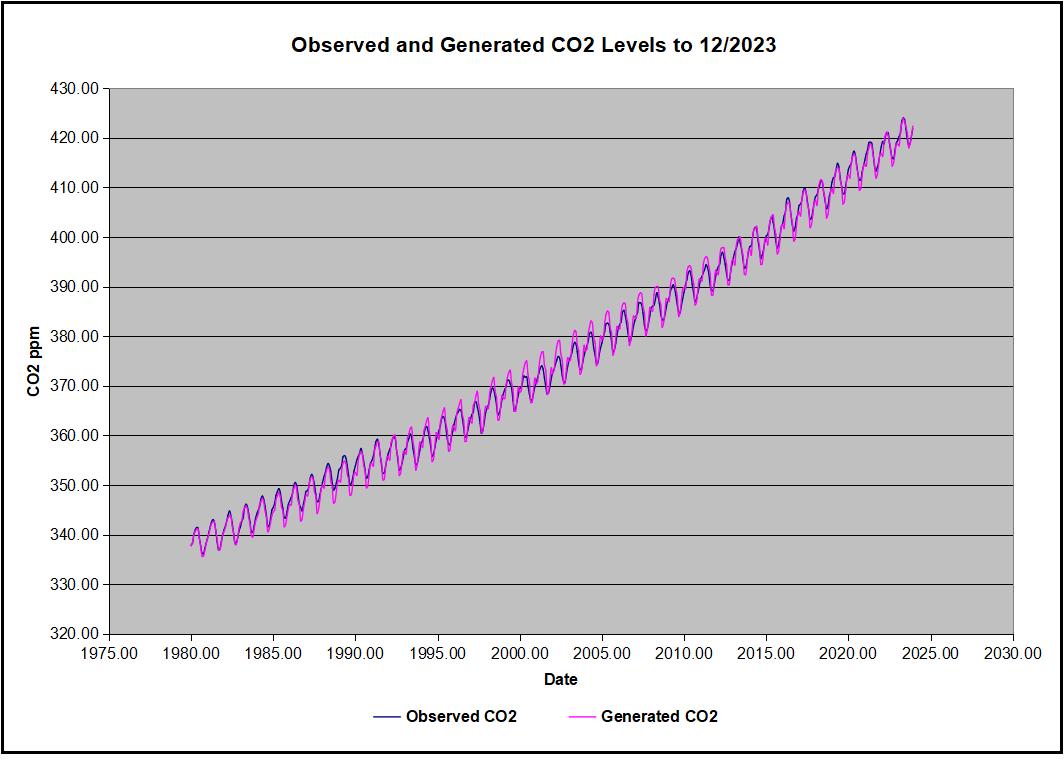

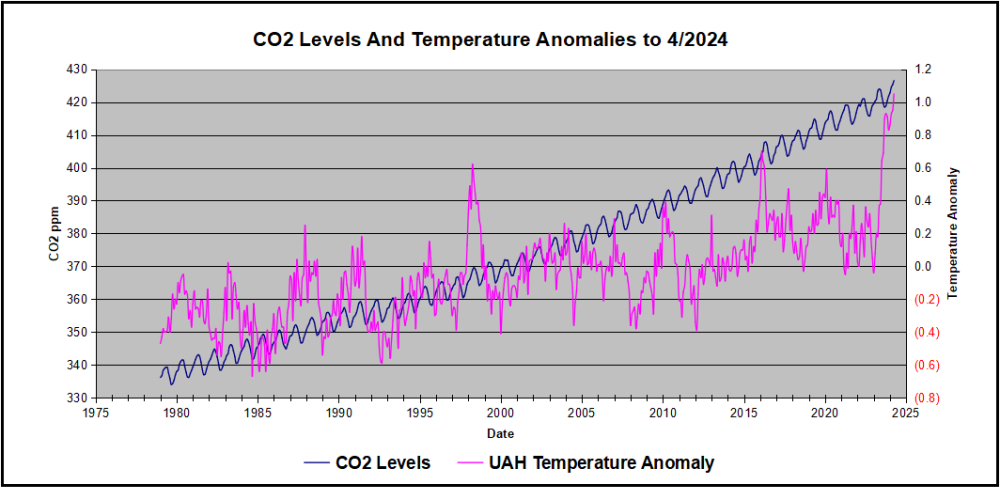

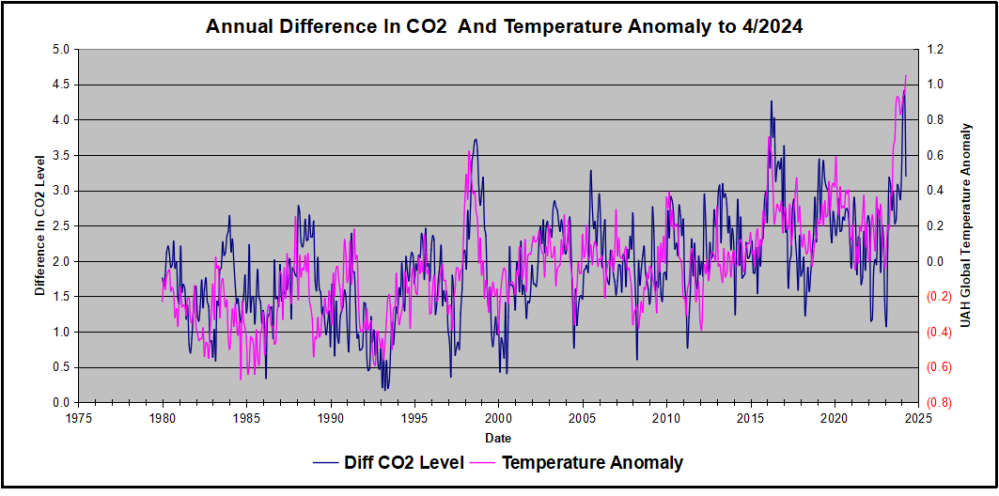

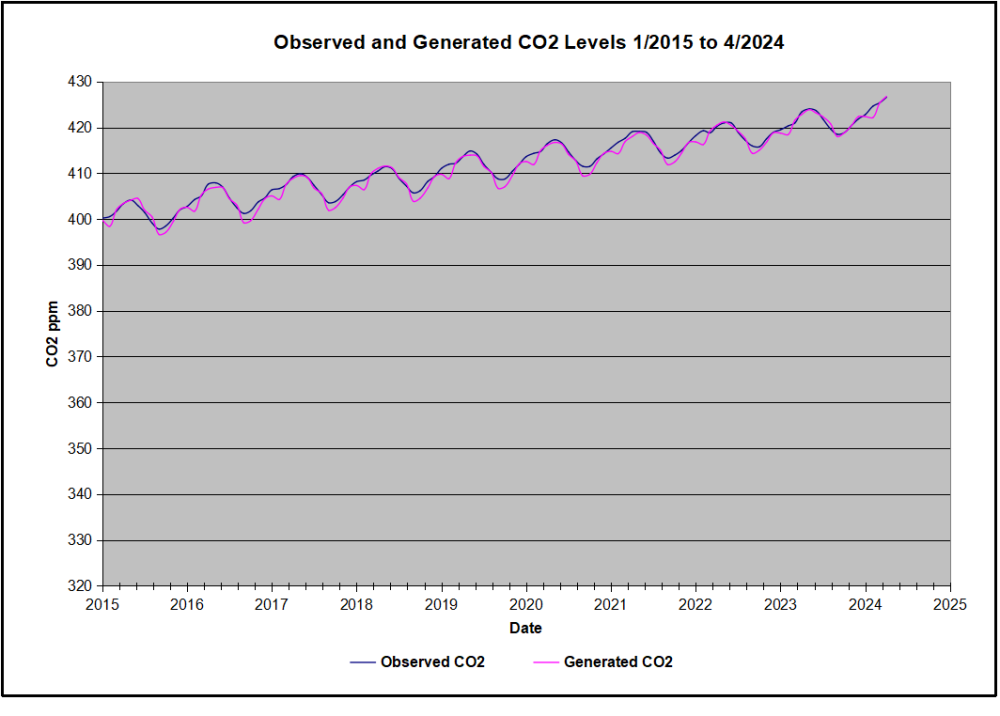

For reference I added an overlay of CO2 annual concentrations as measured at Mauna Loa. While temperatures fluctuated up and down ending flat, CO2 went up steadily by ~60 ppm, a 15% increase.

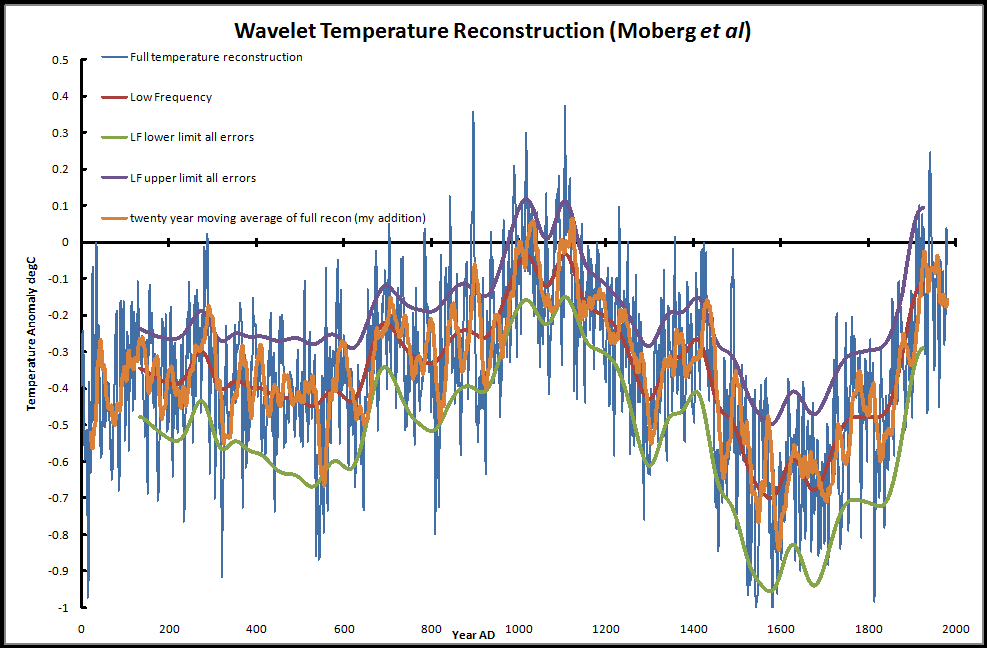

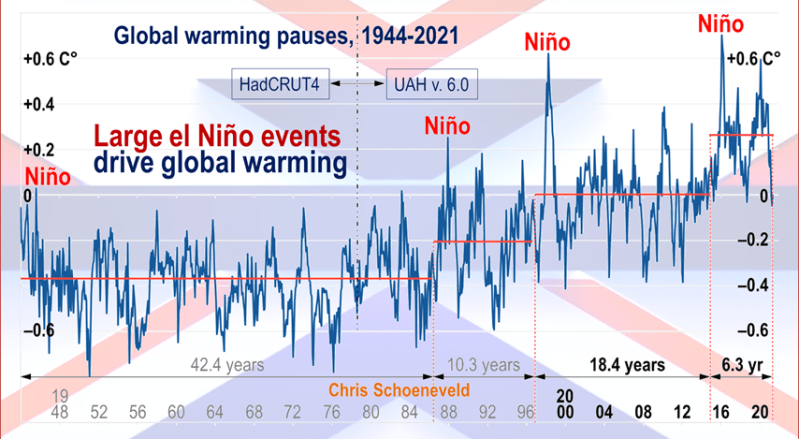

Furthermore, going back to previous warmings prior to the satellite record shows that the entire rise of 0.8C since 1947 is due to oceanic, not human activity.

The animation is an update of a previous analysis from Dr. Murry Salby. These graphs use Hadcrut4 and include the 2016 El Nino warming event. The exhibit shows since 1947 GMT warmed by 0.8 C, from 13.9 to 14.7, as estimated by Hadcrut4. This resulted from three natural warming events involving ocean cycles. The most recent rise 2013-16 lifted temperatures by 0.2C. Previously the 1997-98 El Nino produced a plateau increase of 0.4C. Before that, a rise from 1977-81 added 0.2C to start the warming since 1947.

Importantly, the theory of human-caused global warming asserts that increasing CO2 in the atmosphere changes the baseline and causes systemic warming in our climate. On the contrary, all of the warming since 1947 was episodic, coming from three brief events associated with oceanic cycles. And now in 2024 we have seen an amazing episode with a temperature spike driven by ocean air warming in all regions, along with rising NH land temperatures, now receding from its peak.

Chris Schoeneveld has produced a similar graph to the animation above, with a temperature series combining HadCRUT4 and UAH6. H/T WUWT

See Also Worst Threat: Greenhouse Gas or Quiet Sun?

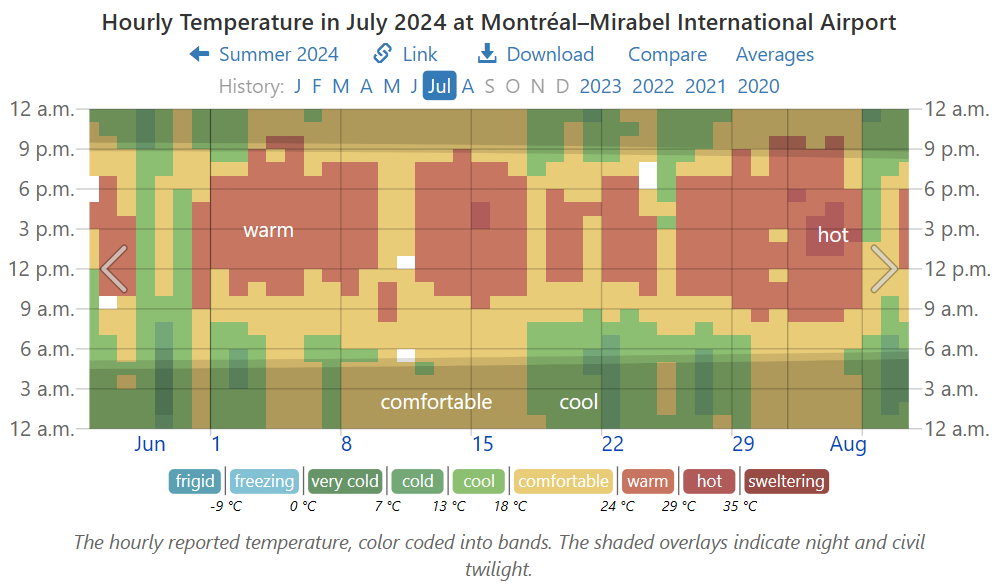

July 2024 Global Temps Little Changed by Land Warming

With apologies to Paul Revere, this post is on the lookout for cooler weather with an eye on both the Land and the Sea. While you heard a lot about 2020-21 temperatures matching 2016 as the highest ever, that spin ignores how fast the cooling set in. The UAH data analyzed below shows that warming from the last El Nino had fully dissipated with chilly temperatures in all regions. After a warming blip in 2022, land and ocean temps dropped again with 2023 starting below the mean since 1995. Spring and Summer 2023 saw a series of warmings, continuing into October, followed by cooling.

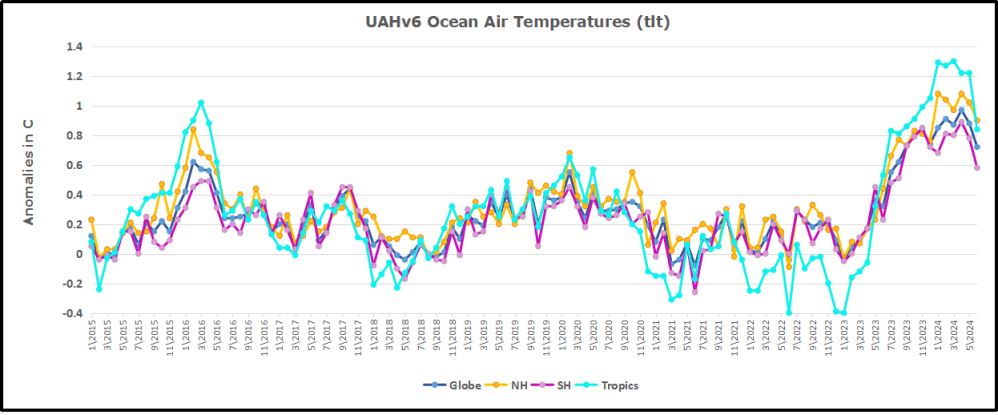

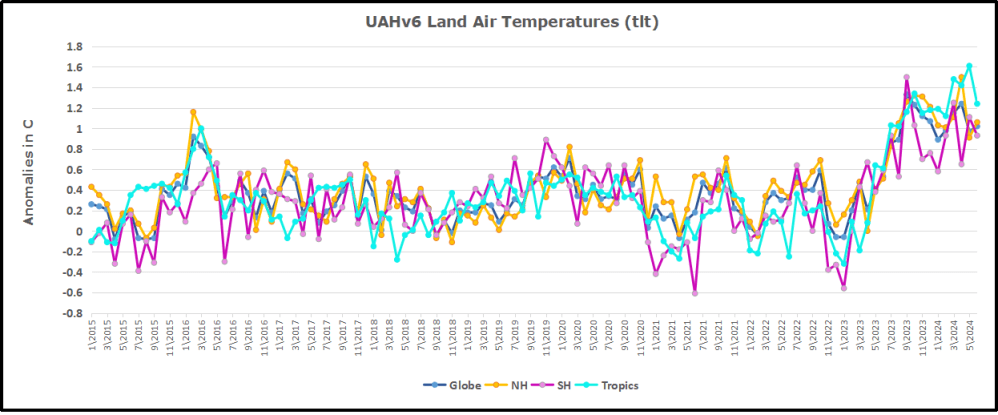

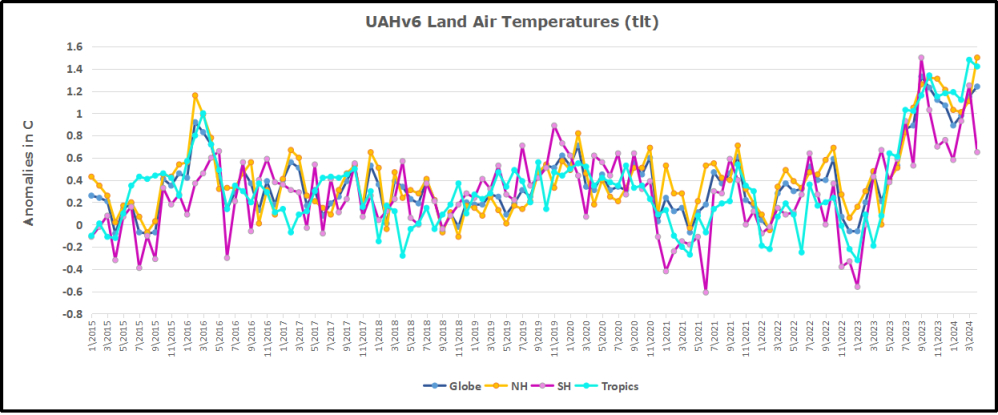

UAH has updated their tlt (temperatures in lower troposphere) dataset for July 2024. Posts on their reading of ocean air temps this month follows the update from HadSST4. I posted last week on SSTs using HadSST4 Oceans Warming Uptick July 2024. This month also has a separate graph of land air temps because the comparisons and contrasts are interesting as we contemplate possible cooling in coming months and years.

Sometimes air temps over land diverge from ocean air changes. Last February 2024, both ocean and land air temps went higher driven by SH, while NH and the Tropics cooled slightly, resulting in Global anomaly matching October 2023 peak. Then in March Ocean anomalies cooled while Land anomalies rose everywhere. After a mixed pattern in April, the May anomalies were back down led by a large drop in NH land, and a smaller ocean decline in all regions. In June all Ocean regions dropped down, as well as dips in SH and Tropical land temps. Now in July all Oceans were unchanged except for Tropical warming, while all land regions rose slightly.

Note: UAH has shifted their baseline from 1981-2010 to 1991-2020 beginning with January 2021. In the charts below, the trends and fluctuations remain the same but the anomaly values changed with the baseline reference shift.

Presently sea surface temperatures (SST) are the best available indicator of heat content gained or lost from earth’s climate system. Enthalpy is the thermodynamic term for total heat content in a system, and humidity differences in air parcels affect enthalpy. Measuring water temperature directly avoids distorted impressions from air measurements. In addition, ocean covers 71% of the planet surface and thus dominates surface temperature estimates. Eventually we will likely have reliable means of recording water temperatures at depth.

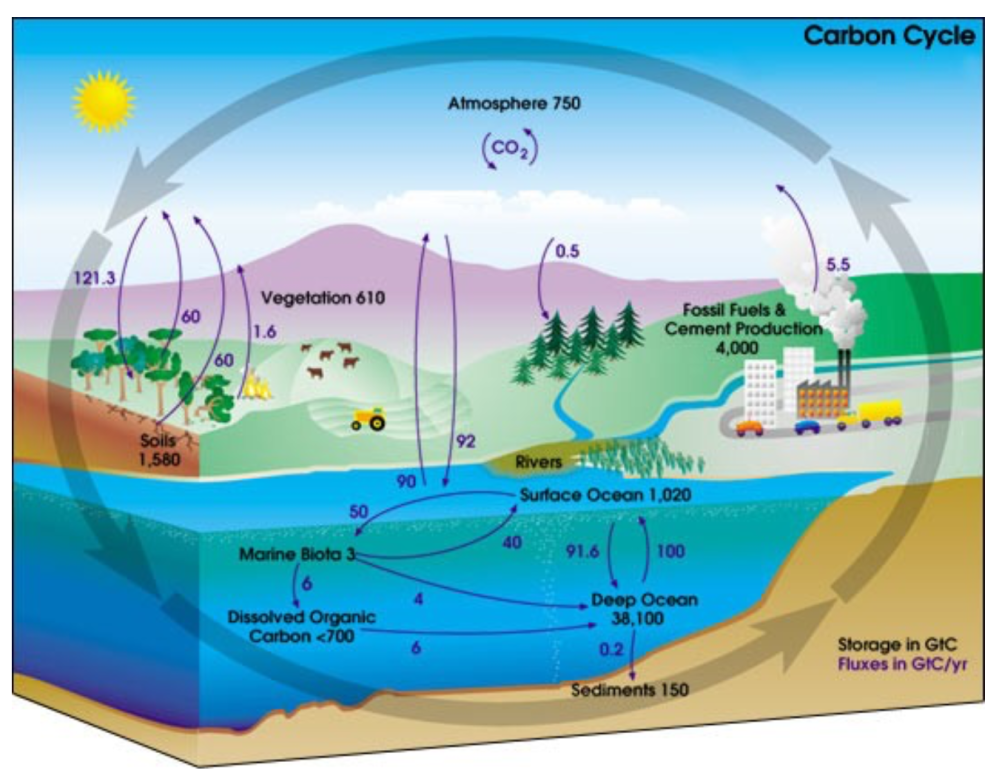

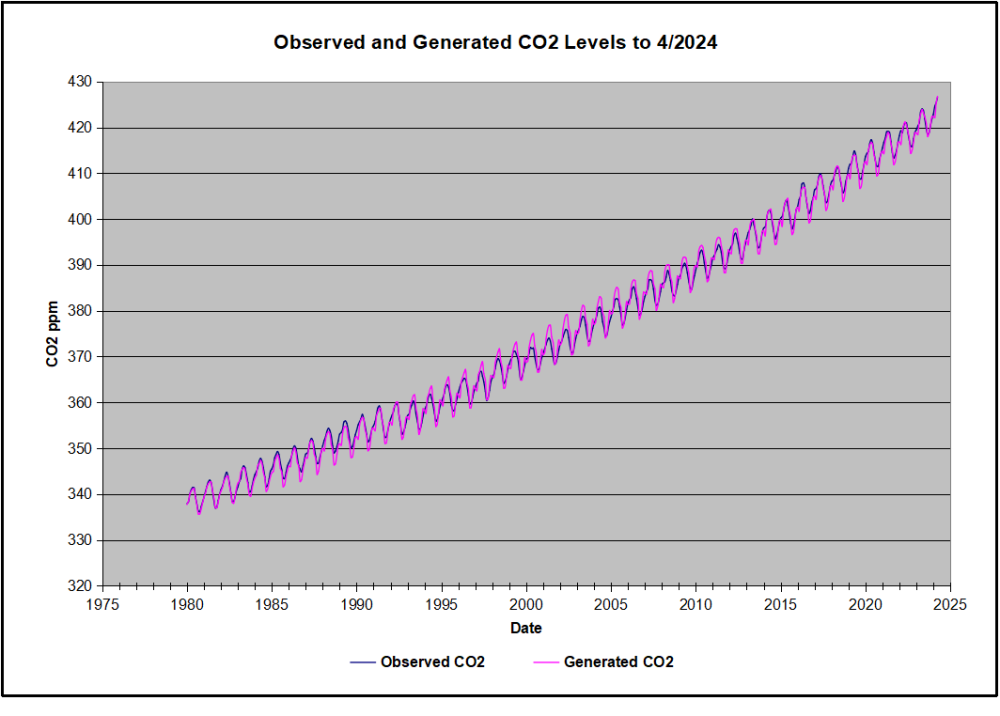

Recently, Dr. Ole Humlum reported from his research that air temperatures lag 2-3 months behind changes in SST. Thus cooling oceans portend cooling land air temperatures to follow. He also observed that changes in CO2 atmospheric concentrations lag behind SST by 11-12 months. This latter point is addressed in a previous post Who to Blame for Rising CO2?

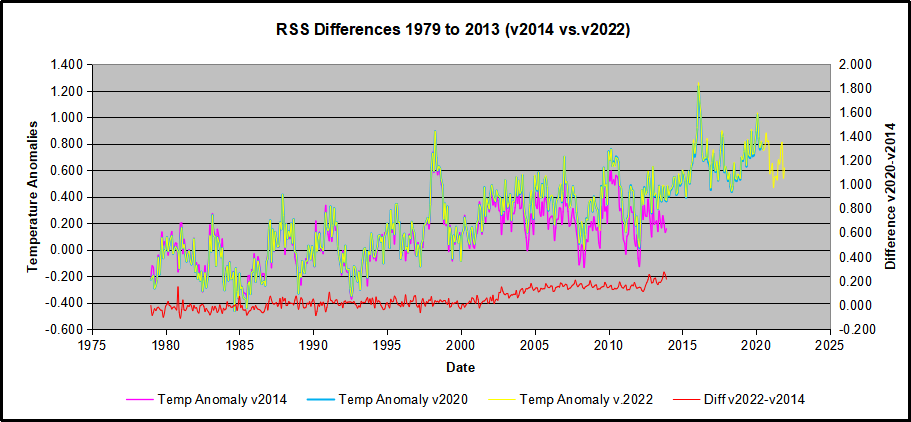

After a change in priorities, updates are now exclusive to HadSST4. For comparison we can also look at lower troposphere temperatures (TLT) from UAHv6 which are now posted for July. The temperature record is derived from microwave sounding units (MSU) on board satellites like the one pictured above. Recently there was a change in UAH processing of satellite drift corrections, including dropping one platform which can no longer be corrected. The graphs below are taken from the revised and current dataset.

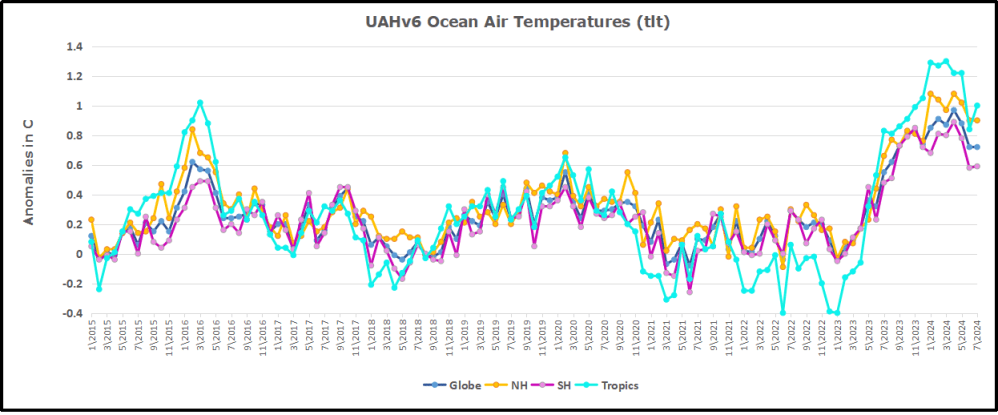

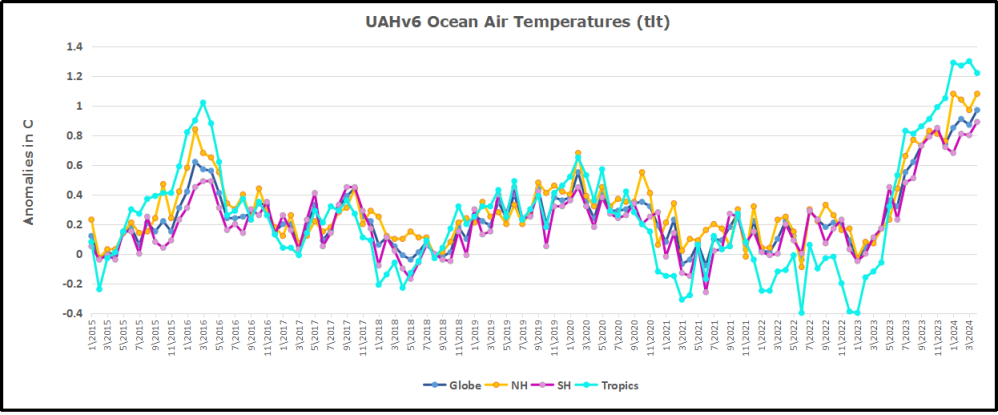

The UAH dataset includes temperature results for air above the oceans, and thus should be most comparable to the SSTs. There is the additional feature that ocean air temps avoid Urban Heat Islands (UHI). The graph below shows monthly anomalies for ocean air temps since January 2015.

Note 2020 was warmed mainly by a spike in February in all regions, and secondarily by an October spike in NH alone. In 2021, SH and the Tropics both pulled the Global anomaly down to a new low in April. Then SH and Tropics upward spikes, along with NH warming brought Global temps to a peak in October. That warmth was gone as November 2021 ocean temps plummeted everywhere. After an upward bump 01/2022 temps reversed and plunged downward in June. After an upward spike in July, ocean air everywhere cooled in August and also in September.

After sharp cooling everywhere in January 2023, all regions were into negative territory. Note the Tropics matched the lowest value, but since have spiked sharply upward +1.7C, with the largest increases in April to July, and continuing through adding to a new high of 1.3C January to March 2024. In April and May that started dropping in all regions. June showed a sharp decline everywhere, led by the Tropics down 0.5C. The Global anomaly fell to nearly match the September 2023 value. Now in July, the Tropics rose slightly while SH, NH and the Global Anomaly were unchanged.

Land Air Temperatures Tracking in Seesaw Pattern

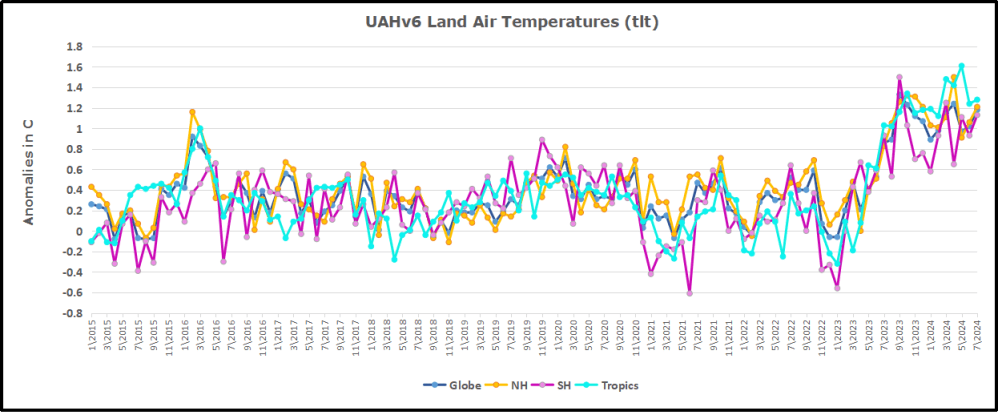

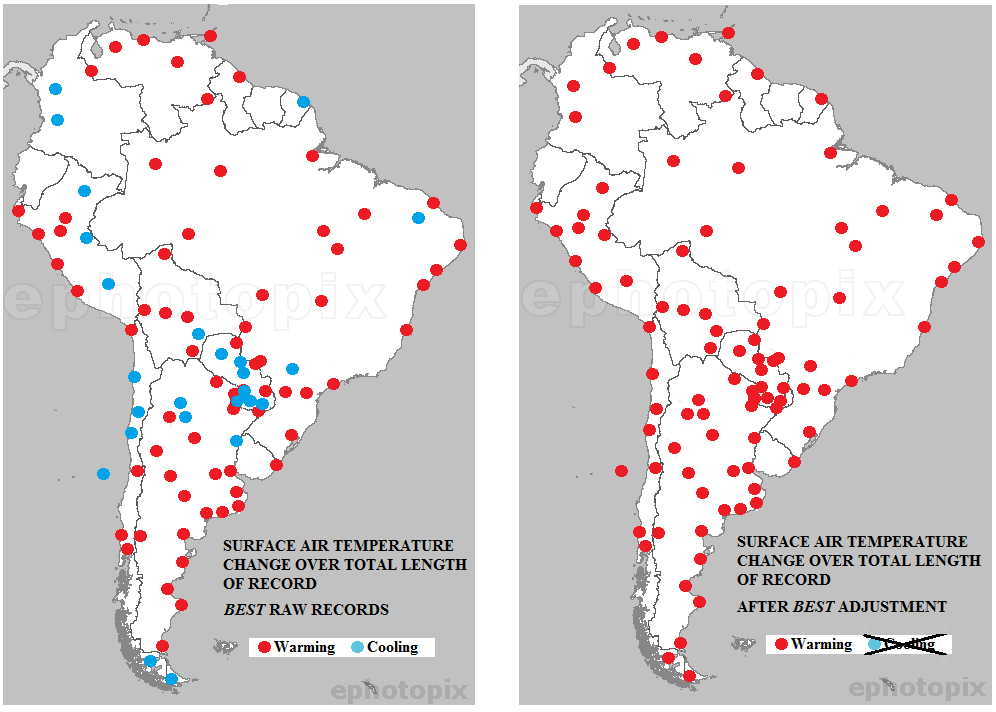

We sometimes overlook that in climate temperature records, while the oceans are measured directly with SSTs, land temps are measured only indirectly. The land temperature records at surface stations sample air temps at 2 meters above ground. UAH gives tlt anomalies for air over land separately from ocean air temps. The graph updated for July is below.

Here we have fresh evidence of the greater volatility of the Land temperatures, along with extraordinary departures by SH land. Land temps are dominated by NH with a 2021 spike in January, then dropping before rising in the summer to peak in October 2021. As with the ocean air temps, all that was erased in November with a sharp cooling everywhere. After a summer 2022 NH spike, land temps dropped everywhere, and in January, further cooling in SH and Tropics offset by an uptick in NH.

Remarkably, in 2023, SH land air anomaly shot up 2.1C, from -0.6C in January to +1.5 in September, then dropped sharply to 0.6 in January 2024, matching the SH peak in 2016. Then in February and March SH anomaly jumped up nearly 0.7C, and Tropics went up to a new high of 1.5C, pulling up the Global land anomaly to match 10/2023. In April SH dropped sharply back to 0.6C, Tropics cooled very slightly, but NH land jumped up to a new high of 1.5C, pulling up Global land anomaly to its new high of 1.24C.

In May that NH spike started to reverse. Despite warming in Tropics and SH, the much larger NH land mass pulled the Global land anomaly back down to the February value. In June, sharp drops in SH and Tropics land temps overcame an upward bump in NH, pulling Global land anomaly down to match last December. Now in July, all land regions rose slightly, pulling the Global land anomaly up by o.16°C. Despite this land warming, the Global land and ocean combined anomaly rose only 0.05°C.

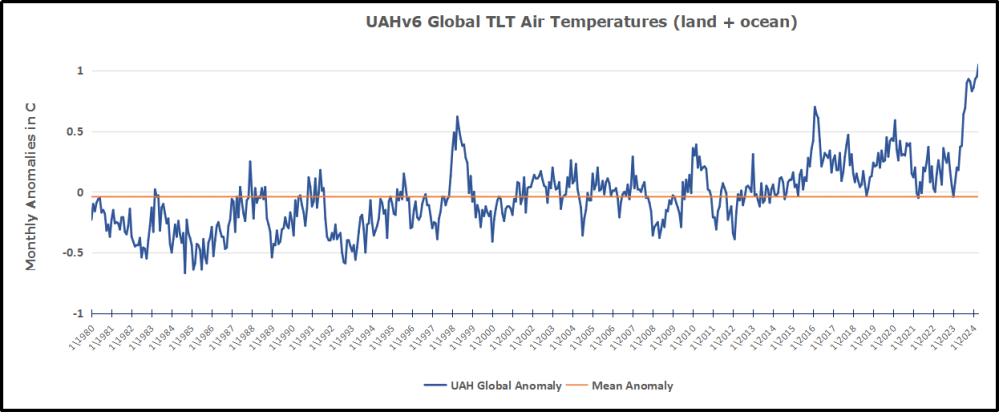

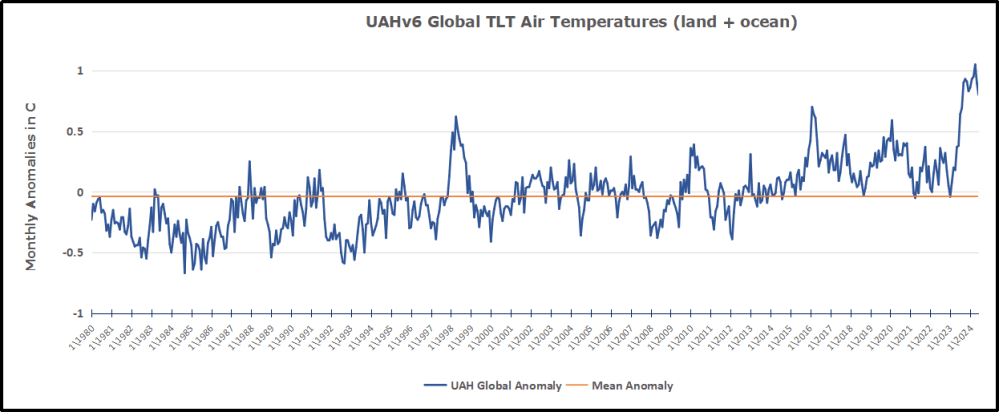

The Bigger Picture UAH Global Since 1980

The chart shows monthly Global anomalies starting 01/1980 to present. The average monthly anomaly is -0.04, for this period of more than four decades. The graph shows the 1998 El Nino after which the mean resumed, and again after the smaller 2010 event. The 2016 El Nino matched 1998 peak and in addition NH after effects lasted longer, followed by the NH warming 2019-20. An upward bump in 2021 was reversed with temps having returned close to the mean as of 2/2022. March and April brought warmer Global temps, later reversed

The chart shows monthly Global anomalies starting 01/1980 to present. The average monthly anomaly is -0.04, for this period of more than four decades. The graph shows the 1998 El Nino after which the mean resumed, and again after the smaller 2010 event. The 2016 El Nino matched 1998 peak and in addition NH after effects lasted longer, followed by the NH warming 2019-20. An upward bump in 2021 was reversed with temps having returned close to the mean as of 2/2022. March and April brought warmer Global temps, later reversed

With the sharp drops in Nov., Dec. and January 2023 temps, there was no increase over 1980. Then in 2023 the buildup to the October/November peak exceeded the sharp April peak of the El Nino 1998 event. It also surpassed the February peak in 2016. After March and April took the Global anomaly to a new peak of 1.05C. The cool down started with May dropping to 0.90C, and in June a further decline to 0.80C. Despite an uptick to 0.85 in July, it remains to be seen whether El Nino will weaken or gain strength, and it whether we are past the recent peak.

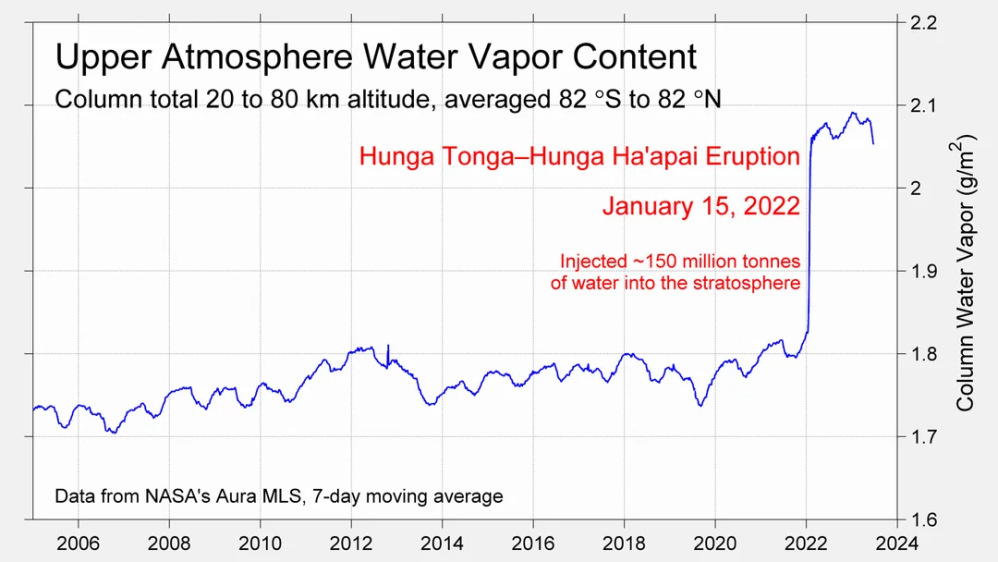

The graph reminds of another chart showing the abrupt ejection of humid air from Hunga Tonga eruption.

TLTs include mixing above the oceans and probably some influence from nearby more volatile land temps. Clearly NH and Global land temps have been dropping in a seesaw pattern, nearly 1C lower than the 2016 peak. Since the ocean has 1000 times the heat capacity as the atmosphere, that cooling is a significant driving force. TLT measures started the recent cooling later than SSTs from HadSST4, but are now showing the same pattern. Despite the three El Ninos, their warming has not persisted prior to 2023, and without them it would probably have cooled since 1995. Of course, the future has not yet been written.