Other posts have addressed the murky science underneath the claim that burning fossil fuels makes the earth warmer, and the alarmist claims that a warmer world is more dangerous than a colder one. This post takes up the issue that even if rising human CO2 emission were causing dangerous warming, what are the likely consequences of policies to cut down on carbon-based energy. Text below in italics comes from sources listed as links at the end.

This issue arises in the US context because presidential candidates of leftist stripes have pledged to do away with fracking operations and forego the resulting boom in natural gas and tight oil production.

The Narrative

“I will ban fracking—everywhere.”

— Elizabeth Warren

“Any proposal to avert the climate crisis must include a full fracking ban on public and private lands.”

— Bernie Sanders

“I favor a ban on new fracking and a rapid end to existing fracking.”

— Pete Buttigieg

“I want you to look in my eyes. I guarantee you, I guarantee you we’re gonna end fossil fuel.”

— Joe Biden

And don’t forget the Democratic 2016 nominee whose election was narrowly averted by the Trump surprise:

“So by the time we get through all of my conditions, I do not think there will be many places in America where fracking will continue to take place.”

– Hillary Clinton in 2016

In other words, she declared her intention to follow the Obama program: Regulate anything that moves until it stops moving.

Some skeptics caution against overreacting to electioneering rhetoric, citing the practical limits of presidential authority to implement a ban on fracking. But “elections have consequences,” executive orders have an impact, and few industries have been subjected to such consistent attack and misinformation. It might be hard to imagine serious proposals to ban, say, farming or at least all grain farms, but it would be theoretically possible to do so by radically increasing imports. Administrative agencies can pursue creative interpretations of the labyrinth of rules and issue aggressive “guidances.” A broad and coordinated set of such actions can slow or outright stop all manner of industrial activities up and down supply chains, including, especially, the construction of vital pipelines and ports. And lest one forget, Congress enacted legislation in 1972 and 1982 to ban oil production on about 90% of America’s offshore domains.

A detailed analysis has been performed by the Global Energy Institute. The updated report is What if . . . Hydraulic Fracturing Was Banned?

The Economic Benefits of the Shale Revolution and the Consequences of Ending It.

The Reality

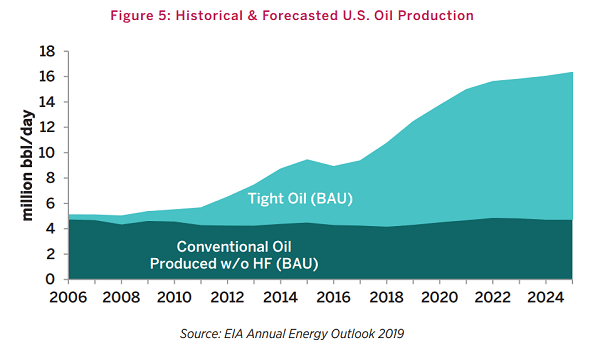

The extraction of oil and gas through the techniques of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (colloquially, “fracking”) has catapulted the United States into leadership of the world’s energy markets. Since 2007, fracking has doubled U.S. oil production and increased gas production by 60%. Instead of a major importer, America is rapidly becoming the largest exporter of oil and is expected to supply the majority of net new energy traded on global markets over the next two decades.

If the U.S. imposed a fracking ban, the supply disruption would trigger the biggest oil and natural gas price spikes in history—almost certainly by more than 200%—which would, in turn, tip the world into recession. Even the expectation that a ban could be enacted would destabilize markets. U.S. imports and the trade imbalance would soar, as would consumers’ spending on energy. To keep the lights on, America would have to nearly double the quantity of coal burned, as well as import up to 1 million barrels of oil per day for dual-fueled power plants that would lose access to natural gas.

“A fracking ban, regardless of motivation, is anchored in magical thinking that non-hydrocarbon energy sources could fill a massive global energy shortfall if the U.S. exited the world stage as a major supplier of oil and natural gas. Both fuels will be critical for the global economy for decades to come. The key issue is not whether wind and solar can supply more energy—they can and will—but whether a future American administration would reverse the progress of the last decade in lowering energy prices and enhancing geopolitical stability.”

—Mark Mills, senior fellow, Manhattan Institute

Supply Impact

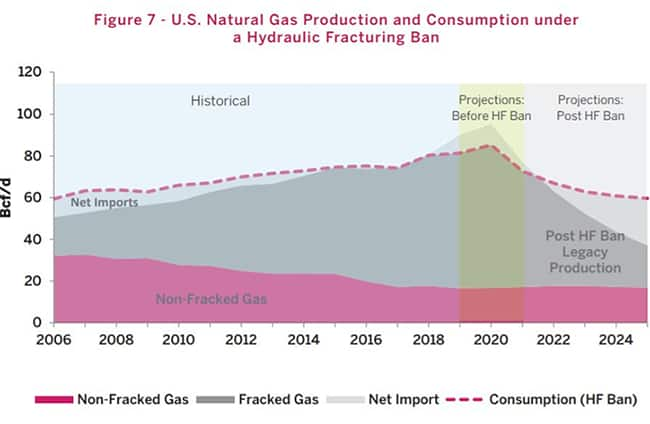

The study is based on what GEI calls conservative assumptions. These include the continued use of hydraulic fracturing in non-tight oil and gas plays, and a 23.7% annual decline rate for existing shale plays. GEI also assumes a drop in gas exports to Mexico, and increase in gas imports from Canada, and a shift from LNG exporting to LNG importing—all designed to close the supply/demand gap that would occur as shale gas is phased out.

“Currently, shale production is about 50.5 Bcf/d or 62 percent of U.S. production. Under a hydraulic fracturing ban, production from existing sources would drop significantly due to the field production decline rates. Similarly, natural gas production from tight gas formations would drop quickly as well, since they rely on hydraulic fracturing to generate production,” GEI said.

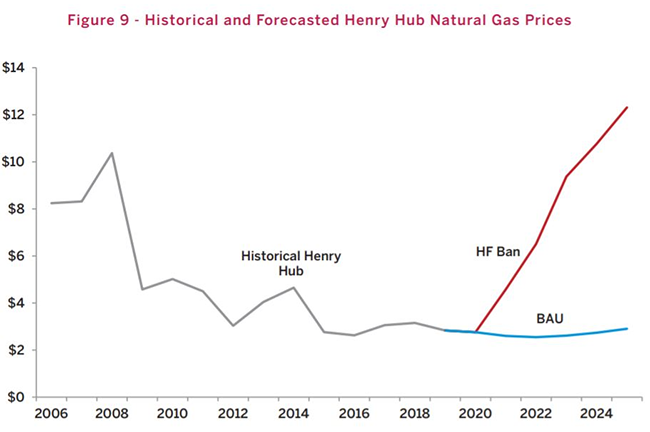

With gas in tighter supply (see graph above), prices would soar to $12/MMBtu by 2025 (2nd graph below).

Economic Impact

With supply for gas and oil constricted, energy prices would rise dramatically. In addition to $12/MMBtu gas, GEI says that West Intermediate crude would reach about $130/bbl by 2025, or more than double today’s price and nearly double the forecast out to 2025.

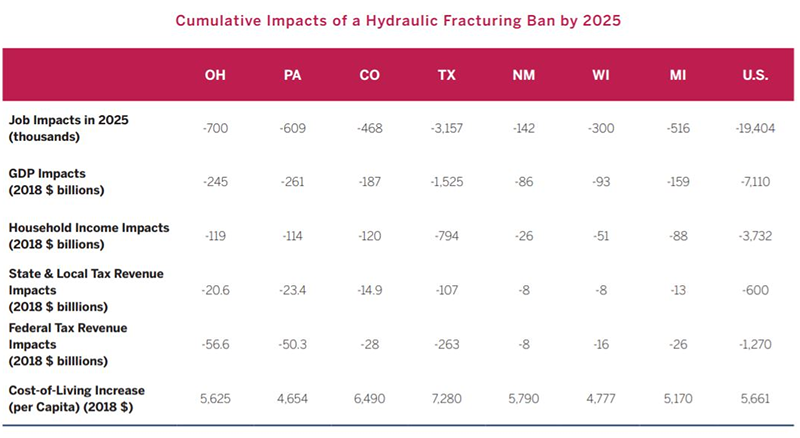

“In 2025, the U.S. would lose around 19 million jobs and $2.3 trillion in GDP. For comparison, this is roughly three times the economic impact of the Great Recession of the late 2010s,” GEI said. “Disallowing hydraulic fracturing would shrink the size of the U.S. energy industry and eliminate its ability to cushion the economy against large swings in prices. A ban on hydraulic fracturing would essentially be the worst of both worlds – low production as if prices were low, while the rest of the economy (in the form of millions of households and businesses) struggles to adapt to a doubling of oil prices and quadrupling of natural gas prices,” it said.

The economic results for the nation and for key energy-producing states (as well as two, Michigan and Wisconsin, which are considered to be close in the 2020 election) is shown below.

Why a US Self-embargo is Unicorns All the Way Down

The fracking ban campaign is neither new nor connected only to the politics of this presidential election cycle. The movement emerged from the intersection of two global trends: the expansion of hydrocarbon production; and a time when many pundits and policymakers believe that an “energy transition” to something different is urgently needed. For example, some 400 domestic and international environmental leaders and organizations petitioned the United Nations in September to demand “a global ban on fracking.”[14] Essentially all fracking production is done in the United States.

A ban on fracking would end U.S. exports, cause imports to soar, and increase the trade deficit by hundreds of billions of dollars. The more serious impact would come from the shock to global markets. Global oil prices swing widely when markets are surprised by even a 1%–2% change in the supply/demand balance. A fracking ban would entail a loss of 7% of global oil production, comparable to the 7% lost with the infamous 1973 Arab oil embargo—an embargo that drove world oil prices up 400% and triggered a global recession.[25] Similarly, the 1979 Iranian revolution took 5% of oil off global markets. Prices rose more than 200%, sparking another global recession.[26] Today, taking shale production off the market would also constitute an additional 17% loss to global markets in the form of natural gas.[27] Higher energy prices would hit global consumers; Americans would pay more than $100 billion a year at the gas pump alone, an average of $1,000 per household.[28] Even a slow 10-year production phase-out would trigger an estimated two-year recession in America and eliminate $270 billion of private investment.[29] There would be some winners: Russia and OPEC would derive huge revenue and geopolitical benefits.

Losing the share of new electricity generation that is now fueled from natural gas (produced by fracking) would push utilities to increase the use of existing underutilized power plants where they’re available, which are mainly coal-fired.[30] That would increase carbon dioxide emissions by some 600%—more than all emissions avoided from wind and solar on U.S. grids.[31]

Regions heavily dependent on natural gas but with minimal coal capacity would be faced with rolling blackouts—such as New England (where gas currently provides 49% of electricity), the Mid-Atlantic region (38%), and the Pacific coast (30%).[32] Some of that shortfall could come from burning oil in the 130 GW of gas-fired turbines designed to be dual-fueled.[33] If fully utilized, those turbines would burn about 1 mmbd of oil (necessarily imported), a 10-fold increase in U.S. oil-fired power generation.

The Impossibility of Filling the Gap

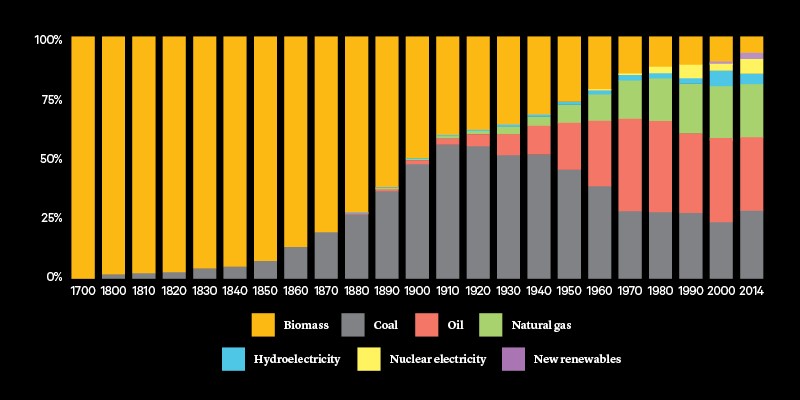

The central motivation for the movement to ban fracking is the global abundance of hydrocarbons at a time when many pundits and policymakers believe that an “energy transition” is urgently needed. But America’s shale production could not be replaced quickly by alternatives, at any price, regardless of climate-change motivations. To the extent that there is an “energy transition” to new technologies, it is happening in slow motion.

Politically popular wind and solar power have become far less expensive and have enjoyed massive global subsidies; but together, they still provide only 1.8% of global energy. The 5 million electric vehicles on all the world’s roads now displace 0.1% of global oil use.[34]

Replacing the quantity of energy produced by fracking in the U.S. shale fields would entail (in energy-equivalent terms) expanding all of America’s solar and wind production by 2,000% more than what has been added in the past decade.[35] Somehow accomplishing that miracle wouldn’t help the 99% of Americans driving oil-fueled cars. In fact, because the hydrocarbon market is global, the entire world would have to increase global wind and energy supply by 500% to replace the energy that would be lost from an American fracking ban—never mind the additional energy needed to fuel global economic growth.[36]

Resources:

New Study by Global Energy Institute Puts Impact of Fracking Ban at $7.1 Trillion Over Four Years

A Fracking Ban Would Trigger Global Recession

New Chamber Analysis Quantifies Economic Risks of Proposed Fracking Ban

U.S. Chamber of Commerce says proposed fracing ban puts Texas economy at risk

Good post. My thought this morning was the time it takes for an energy transition such as proposed by the energy innumerate. My grandparents grew up using horses, my parents remembered when electricity came to their farms, and I remember when natural gas replaced coal in my home. I see no reason that an energy transition to a massively different energy mix would take place any faster, that is to say before my grandchildren get to my age, i.e. 60 years or so.

LikeLike

Thanks Roger. You’re on the same page as Bill Gates, source of this chart:

More at https://rclutz.wordpress.com/2018/06/28/on-energy-transitions/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Roger, actually I was thinking of another post where Richard Rhodes recounts how past societies were transformed by energy transitions.

https://rclutz.wordpress.com/2018/06/30/energy-changes-society-transition-stories/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ron,

We are scheduled for a propane delivery later this week. Our cost for a gallon will be around $1.80/gallon at this time of year. By chance did you notice if propane costs were evaluated in the various scenarios?

LikeLike

kakatoa, not in that study. Maybe you can get what you want here:

https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/propane

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Climate Collections.

LikeLike