The New York Post Editorial Board reviews the New York Attorney General’s blundering performance before the Judge in their investor fraud case against Exxon. Their article is New York AG’s office totally disgraced itself in the Exxon trial. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Closing arguments finished up Thursday in the People of New York v. ExxonMobil — a trial that has utterly disgraced the people’s representatives, prosecutors from the state Attorney General’s Office.

Time and again, state Supreme Court Justice Judge Barry Ostrager chided the prosecution — for being unprepared, for indulging in “agonizing, repetitious questioning about documents that are not being disputed”; for pretending a witness was an expert when she wasn’t; for presenting an expert (paid $1,050 an hour) who wouldn’t stop “rambling” and more.

At one point, he snapped: “OK, that’s the fifth time that he has given you the same answer.” At another, he all but accused the state of manipulating Exxon’s stock price on the basis of false information — in a trial where the state was trying to show that Exxon was doing that.

In a final bit of self-disgrace, late Thursday the prosecutors dropped two of their three main charges — the ones that required proving intent.

All that’s left is a charge under the Martin Act, which allows for criminal guilt for an accidental misrepresentation that might mislead the public. But the state failed to even produce any clear evidence that Exxon ever misled the public in any respect, even inadvertently.

That’s a huge comedown for a prosecution that opened under the banner “#ExxonKnew.”

To be clear, the main blame for this debacle falls on disgraced former AG Eric Schneiderman, who started the whole thing as an exercise in headline-hunting back in 2015. He handed off the actual work to subordinates who repeatedly revised the entire theory of the case — that is, the wrong they claimed Exxon had committed — with the charges growing less explosive every time.

They originally claimed Exxon had suppressed research — when in fact its scientists have always published freely, and the company has openly discussed the risks of climate change and so on in its annual reports and on its website.

Then they suggested the company had deceived investors by “overstating” its assets by “trillions.” But it turned out Exxon had clearly disclosed all the relevant info.

Finally, they claimed it used one risk-assessment standard in public, another in private. But the Securities and Exchange Commission cleared Exxon on that front before this trial even opened.

It seems the prosecutors feared it would just be too humiliating to admit they had nothing, and hoped they’d somehow stumble on . . . something.

Still, Thursday’s final retreat, dropping most charges at the very end, was a shocker. It left the judge dismissing those charges “with prejudice,” so the state can never refile them. And Exxon’s infuriated lawyers say those claims “have cost in many respects the most severe reputation harm to the company and to the executives,” so they want still stronger sanctions.

Judge Ostrager has 30 days to issue a decision. The prosecutors are surely praying he’ll find the Martin Act gives them so much leeway that he actually has to find Exxon guilty. If so, it’ll be a blaring alarm to businesses to have nothing to do with New York, because they have no hope of a fair break here.

Otherwise, the judge should explore every possible option for censuring the state’s attorneys — whose abuse of power here has been utterly mind-blowing.

Background from Previous Post

A legal summary of this week’s proceedings comes from Seth Kerschner Laura Mulry article at White & Case

Trial Concludes for Exxon in New York Climate Change Investor Fraud Case. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Overview

In New York Supreme Court, Exxon was on trial for allegedly misleading investors about the business costs of climate change. The central allegation was that Exxon fraudulently used two distinct sets of metrics to calculate financial risks relating to climate change: one that was shared with investors and another that was used internally. New York State alleged that the practice exposed investors to greater risks than Exxon had disclosed and inflated the company’s value. Exxon maintained that it made accurate disclosures about the two cost metrics to investors, that the state was conflating the two metrics, and that there was no material impact to Exxon regardless of which metric it applies. The state is seeking between $476 million and $1.6 billion as the basis for a shareholder restitution fund, among other relief. The outcome of the case could have significant implications going forward on (i) how companies disclose and internally account for climate change risks and (ii) the outcomes of future climate change litigation.

(Left) New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood announced her office’s lawsuit against Exxon for climate fraud. October 24, 2018. (Right) Attorney General of New York, Letitia James took over January 6, 2019 and has also opened a civil investigation into President Donald Trump’s business dealings.

The bench trial commenced on October 22, 2019 and was the first lawsuit to go to trial in the United States that addresses how companies manage and disclose climate change-related risks. The New York Attorney General (NYAG) filed the civil lawsuit against Exxon Mobil Corporation (Exxon) in October 2018; it was the culmination of an investigation by NYAG that began in 2015. NYAG alleged statutory and common law securities fraud claims, however, in its closing remarks on November 7, 2019, NYAG dropped two of the four fraud claims. NYAG’s remaining claims include alleged violations of the state’s Martin Act, one of the strictest anti-fraud laws in the country that does not require an intent to defraud or knowledge of fraud for there to be a violation of the law, and a persistent fraud claim. NYAG requests injunctive relief, damages, disgorgement of all amounts gained as a result of the alleged fraud, and restitution.

NYAG asserted that Exxon engaged in a “longstanding fraudulent scheme” to deceive investors by providing misleading statements that (i) Exxon was effectively managing risks posed by regulations to address climate change, such as carbon taxes, and (ii) such regulations did not pose a significant risk to the company. NYAG asserted that Exxon’s internal practices were inconsistent with these statements, were undisclosed to investors, and exposed the company to greater risk from climate change regulation than investors were led to believe.

According to the NYAG complaint, Exxon used internal climate change cost projections that differed from publicly-disclosed projections and are in alleged violation of US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. Exxon claimed NYAG is trying to show a false discrepancy by conflating two cost projections that serve different purposes. NYAG claimed that Exxon provided misleading statements to investors in reports that Exxon drafted in response to shareholder proposals and resolutions requesting information about climate change-related risks, its 2015 Corporate Citizen Report, and in its 2014 and 2016 proxy statements, among other public documents. NYAG asserted that Exxon’s alleged climate cost misrepresentations are material to the company’s investors, who include public pension funds in New York and around the United States that hold billions of dollars of Exxon stock.

To account for the impact of future climate change regulations, Exxon stated that it “rigorously and consistently” applied an escalating proxy cost of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (together, GHGs) to its business, according to NYAG’s complaint. NYAG claimed, however, that Exxon’s GHG proxy cost representations were materially false and misleading because Exxon did not in fact apply the GHG proxy cost it represented to investors in its business decisions. NYAG claimed that, in projecting its future costs for purposes of making investment decisions, conducting business planning, and assessing oil and gas reserves, Exxon applied either (i) an undisclosed, lower set of GHG proxy costs in its internal corporate guidance, (ii) an even-lower cost based on existing climate regulations that held flat for decades into the future or (iii) no GHG-related costs at all. Exxon maintained that it made accurate disclosures about the two cost metrics to investors and claimed that NYAG is manipulating the content of such disclosures to make it appear as though Exxon misled the public.

The linchpin of the case may rest on whether Exxon conflated two distinct climate change cost projections. Exxon’s publicly-disclosed GHG proxy cost assumed carbon costs would be significantly higher than the internal GHG cost estimate. Exxon did not dispute that it used two distinct projections for the future impacts of climate regulations and argued that each had a legitimate business purpose: the publicly-disclosed GHG proxy cost was used to project global energy demand (and future prices) and the GHG cost was a proprietary internal number used to evaluate investment opportunities. Exxon representatives, including former Chairman and CEO Rex Tillerson, testified that Exxon’s publicly-disclosed GHG proxy cost represented a “macro level” assessment of climate change mitigation policies that Exxon expects to see adopted around the world, from fuel efficiency standards in the United States to carbon taxes in Europe, and was used in a data guide used by the company. Exxon’s position is that the different, lower GHG costs that Exxon used internally represented “micro level” direct costs and capital projects at specific Exxon facilities and were informed by a more limited set of regulations applicable to specific projects. Exxon has contended in court that the publicly-disclosed GHG proxy cost, which is a purported demand-side estimate of how future regulations, like a carbon tax, would depress global demand for oil, is only one part of its climate cost calculations. NYAG argued that Exxon obfuscated differences in the two accounting projections and a reasonable investor had every reason to believe that Exxon was using the two sets of costs interchangeably.

Exxon maintains that there was and would be no impact on its value or finances, including corporate earnings, regardless of whether it applied a higher or lower GHG cost estimate. Exxon asserted that NYAG failed to identify a specific oil or gas project investment decision that would have been swayed by applying the higher GHG proxy cost and that the practice of having two distinct cost metrics had no impact on how investors assessed the company.

Richard Auter, the head of the Exxon audit team at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), testified that (i) he was not aware of any attempt by Exxon to conceal or manipulate the two cost metrics and (ii) GHG proxy costs do not have a material impact on Exxon’s financial health. Mr. Auter stated that the publicly-disclosed GHG proxy costs “were part of management’s planning and budgeting process, but they do not reflect real costs in many situations.”

NYAG claimed that Exxon’s failure to employ the publicly-disclosed GHG proxy costs was most prevalent in its projections for investments with high GHG emissions. Applying the publicly-disclosed GHG proxy costs to these investments would have had a particularly significant negative impact on the company’s economic and financial projections and assessments, according to NYAG. NYAG alleged that using the lower cost estimate for future GHG costs made projects with high GHG emissions look more attractive than those projects would have looked if the higher GHG proxy cost were applied. NYAG stated that Exxon chose not to use the higher, publicly-disclosed GHG proxy costs in connection with 14 oil sands projects in Canada, which allegedly resulted in understating costs in the company’s cash flow projections by more than $25 billion. Bitumen from oil sands is harder to extract and then must be upgraded into synthetic crudes, so the extraction process from oil sands projects typically emits higher GHG emissions than other oil and gas upstream operations. NYAG claimed that, while corporate estimates projected GHG prices continuing to rise up to $80 per ton in 2040, Exxon planners in Canada applied a cost estimate that held flat at $24 per ton through to the end of the assets’ projected life (decades into the future) and didn’t apply to all of the assets’ GHG emissions.

Throughout the three-year probe and trial, NYAG claimed that Exxon senior management sanctioned the alleged fraudulent conduct, including Mr. Tillerson. NYAG stated that Mr. Tillerson knew for years that the company’s GHG proxy cost representations were misleading, but allowed the gap between the two cost metrics to persist. NYAG alleged that, in May 2014, Exxon’s corporate greenhouse gas manager gave a presentation to the company’s senior management, including Mr. Tillerson, that warned that the way the company had been accounting for climate risks was misleading and recommended aligning the cost metrics in evaluating investments. NYAG asserted that, after Exxon revised its internal guidance, Exxon’s planners realized that applying the increased GHG proxy cost figures would result in severe consequences to its economic and financial projections, such as “massive GHG costs” and “large write-downs” (i.e., reductions in estimated volume) of company reserves. NYAG claimed that, when confronted with the negative impacts from applying GHG proxy costs in a manner consistent with the company’s representations to investors, Exxon’s management directed the company’s planners to adopt what an Exxon employee allegedly called an “alternate methodology.” NYAG claimed that Exxon then applied only the existing GHG-related costs presently imposed by governments (i.e., legislated costs) and assumed that those existing costs would remain in effect indefinitely into the future, contrary to the company’s repeated representations to investors that it expects governments to impose increasingly stringent climate regulations in the future. By applying this “alternate methodology,” NYAG alleged that Exxon (i) avoided the significant write-downs it would have incurred had it abided by its stated risk management practices and (ii) failed to take into account significant GHG costs resulting from expected climate change regulation.

Climate Activists storm the bastion of Exxon Mobil, here seen without their shareholder disguises.

Exxon’s counsel argued that certain of NYAG’s key Exxon investor witnesses are politically-motivated and bought the company’s stock with the sole purpose to lobby the company on climate change issues. Exxon noted that one such investor, the New York City comptroller’s office, supports efforts to divest from fossil fuels.

In its closing remarks, NYAG abruptly dropped its common law fraud and equitable fraud claims. Exxon’s counsel responded that NYAG dropped the claims for strategic purposes before the judge could rule against them due to a lack of evidence and indicated that the two dropped claims caused severe reputational harm to the company and its executives, including Mr. Tillerson in particular. Exxon’s counsel stated that Exxon and its officials deserved a ruling to clear their reputations. The court dismissed the two claims with prejudice and invited Exxon’s counsel to submit post-trial briefing on whether Exxon had a right to a stipulation stating that NYAG lacked evidence to prove the dismissed fraud claims at trial.

Exxon and other energy companies are also the subject of other climate change lawsuits brought by (i) local and state governments seeking damages to help pay for the costs imposed by rising seas and extreme weather caused by climate change and (ii) children and non-profit organizations that claim that the federal and state governments are responsible for preventing and addressing the consequences of climate change. [For more information on climate change litigation see links at end.]

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Attorney General commenced an investigation of Exxon in 2015 similar to that of NYAG’s and filed a lawsuit against Exxon on October 24, 2019 for alleged violations of Massachusetts’ investor and consumer protection laws relating to the company’s climate change-related disclosure and advertising. Exxon has fought the New York and Massachusetts investigations in courtrooms. In a New York federal court, a judge earlier this year rejected Exxon’s plea to block the dual investigations. Exxon has argued that the states’ attorneys general were violating Exxon’s First Amendment right to free speech relating to climate change. Exxon has asserted that the claims are politically-motivated, targeting energy companies to be held accountable for climate change.

The three-week bench trial in New York began on October 22, 2019 and the parties have until November 18, 2019 to file post-trial submissions. The presiding Justice Barry Ostrager has said that he will issue a ruling within 30 days after such submission deadline, with a verdict expected sometime in mid-December. NYAG requested that the court (i) enjoin Exxon from violating New York law, (ii) direct a comprehensive review of Exxon’s failure to apply a proxy cost consistent with its representations and the economic and financial consequences of that failure, (iii) award damages caused, directly or indirectly, by the fraudulent and deceptive acts, (iv) award disgorgement of all amounts obtained in connection with the alleged violations of law and all amounts by which Exxon has been unjustly enriched, (v) award restitution of all funds obtained from investors in connection with or as a result of the alleged fraudulent and deceptive acts, and (vi) award the state its costs and fees, including attorney’s fees.

The decision reached in this case is likely to be cited in future climate change litigation. If Exxon prevails, litigation over companies’ climate change-related disclosure could wane.

Companies should be on alert that they could be scrutinized by shareholders, governmental officials, and the public for how they disclose and internally account for climate change-related risks. It may be prudent for companies to align publicly-disclosed climate-related metrics and methodologies with their internal climate-related risk management and accounting practices. At a minimum, companies should ensure that their public disclosure is not misleading and consider any appropriate disclosure on internal climate-related metrics used in business decisions or in the preparation of publicly-disclosed financial information.

The case is People of the State of New York v. ExxonMobil Corp., case number 452044/2018, in the Supreme Court of the State of New York, County of New York. NYAG’s October 24, 2018 complaint can be found here. Exxon’s October 7, 2019 pre-trial memorandum can be found here.

Click here to download PDF.

Background: Inside “Blame Big Oil” Litigation

Legal Calamity: Climate Nuisance Lawsuits

Critical Climate Intelligence for Jurists (and others)

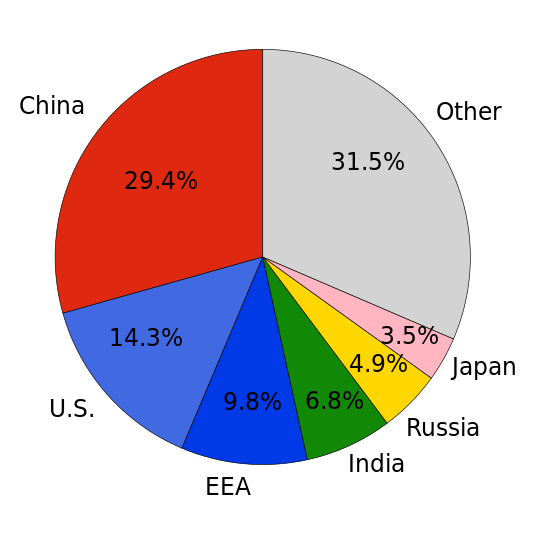

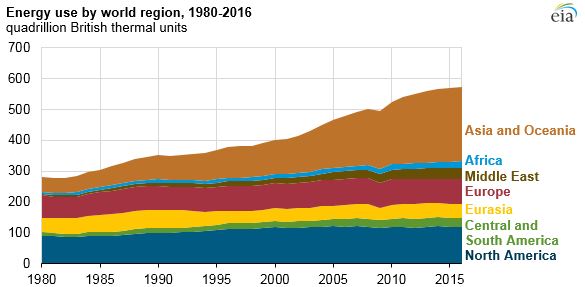

If we look at the situation by part of the world, we see an even more concerning pattern.

If we look at the situation by part of the world, we see an even more concerning pattern. The group US+EU+Japan has been able to reduce its CO2 emissions by 5% since 2005. Emissions were slowly rising between 1981 and 2005. There was a dip at the time of the Great Recession of 2008-2009, followed by a downward trend. A person might get the impression that CO2 emissions for the EU tend to rise during periods when the economy is doing well and tend to fall when it is doing poorly.

The group US+EU+Japan has been able to reduce its CO2 emissions by 5% since 2005. Emissions were slowly rising between 1981 and 2005. There was a dip at the time of the Great Recession of 2008-2009, followed by a downward trend. A person might get the impression that CO2 emissions for the EU tend to rise during periods when the economy is doing well and tend to fall when it is doing poorly. The group that is simply outstanding for population growth is the Remainder Group, with 35% growth between 1997 and 2018. A big part of this population growth comes from improved sanitation and basic medical care, such as antibiotics. With these changes, a larger percentage of the babies that are born have been able to live to maturity.

The group that is simply outstanding for population growth is the Remainder Group, with 35% growth between 1997 and 2018. A big part of this population growth comes from improved sanitation and basic medical care, such as antibiotics. With these changes, a larger percentage of the babies that are born have been able to live to maturity.

Climate modelers keep telling us about what could happen, if indeed we use too much fossil fuel. In fact, the climate currently is changing, bolstering this point of view.

Climate modelers keep telling us about what could happen, if indeed we use too much fossil fuel. In fact, the climate currently is changing, bolstering this point of view. If we are in danger of collapse from low prices, renewables would not seem to be of much assistance unless they (a) are significantly less expensive than fossil fuels and (b) can be scaled up sufficiently rapidly to more than replace fossil fuels. Neither of these seems to be a possibility.

If we are in danger of collapse from low prices, renewables would not seem to be of much assistance unless they (a) are significantly less expensive than fossil fuels and (b) can be scaled up sufficiently rapidly to more than replace fossil fuels. Neither of these seems to be a possibility.

It seems to me that climate modelers should be considering more reasonable scenarios regarding fossil fuel consumption. One scenario which should be considered is the possible near term collapse of several governmental organizations, such as the European Union, World Trade Organization, and the governments of several oil exporting countries. Such a model would be more realistic than one in which energy consumption continues to grow indefinitely.

It seems to me that climate modelers should be considering more reasonable scenarios regarding fossil fuel consumption. One scenario which should be considered is the possible near term collapse of several governmental organizations, such as the European Union, World Trade Organization, and the governments of several oil exporting countries. Such a model would be more realistic than one in which energy consumption continues to grow indefinitely.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65243326/1.0.jpg)