Climate Pacemaker: The AMOC

Update May 19, 2015 text added at end.

We hear a lot about CO2 as climate’s “control knob, but about the oceans’ pacemaker, AMOC? Not so much.

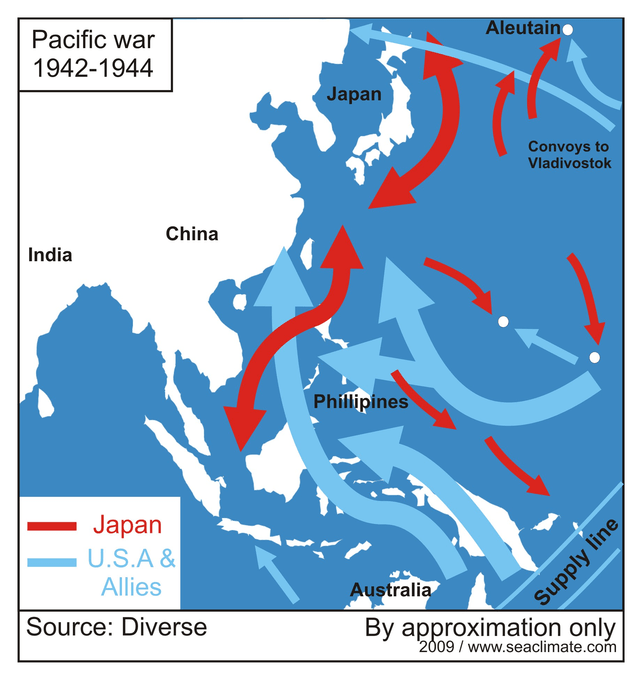

In the Water World post, I referenced the match between SSTs (sea surface temperatures) as recorded in HadISSAT and the IPO, an index of SSTs in the Eastern Pacific: North, Central and South. This is a brief discussion of the Atlantic role in shaping climate patterns, especially in Europe and North America.

The Big Picture

Since global average temperatures are dominated by the oceans as measured by SSTs, it is significant that multidecadal cycles are presently shifting from warmer phases to cooler. The PDO entered its cooler period recently, and the current weak El Nino is evidence of this. (Pacific Decadal Oscillation is an index of Northeastern Pacific based upon ~30-year periods, warm when El Ninos dominate, and cool when La Ninas rule.)

Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). Source: http://www.appinsys.com/globalwarming/SixtyYearCycle.htm

Now the focus is on the Atlantic SSTs and what to expect from the AMO (Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation), which has peaked and is likely to trend downward. In the background is a large scale actor, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) which is the Atlantic part of the global “conveyor belt” moving warm water from the equatorial oceans to the poles and back again.

The notion of the AMOC as the climate pacemaker derives from its role in conveying Pacific shifts into the Atlantic.

“An index of AMOC variability is defined, and the manner in which key variables covary with it is determined. In both models the following is found. (i) AMOC variability is associated with upper-ocean (top 1 km) density anomalies (dominated by temperature) on the western margin of the basin in the region of the Mann eddy with a period of about 20 years. These anomalies modulate the trajectory and strength of the North Atlantic Current. The importance of the western margin is a direct consequence of the thermal wind relation and is independent of the mechanisms that create those density anomalies. (ii) Density anomalies in this key region are part of a larger-scale pattern that propagates around the subpolar gyre and acts as a “pacemaker” of AMOC variability. (iii) The observed variability is consistent with the primary driving mechanism being stochastic wind curl forcing, with Labrador Sea convection playing a secondary role.”

http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00460.1

The Atlantic Leading the Stadium Wave

The critical role of the AMOC and the Atlantic’s global influence is described as part of a “stadium wave” by which the effects ripple throughout all the ocean oscillations.

“A warm (cool) Atlantic triggers a cascade of polarity changes in participating teleconnections, resulting in a cooling (warming) hemispheric climate signal about 30 years later – the “stadium wave”. The periodicity of changes in the North Atlantic AMO appears to be largely governed by the Atlantic sector of the meridional overturning circulation (AMOC). As the cascade of atmospheric and lagged oceanic teleconnections converts a warm (cool)-Atlantic-born signal into a Pacific cooling (warming) signal, the AMOC is re-configuring the Atlantic SST signature. By the time the Pacific begins to cool (warm) as a result of an initially warm (cool) North Atlantic, the North Atlantic, itself, is cooling (warming). The conflated result of temperature profiles within each oceanic basin is a cooling (warming) hemisphere, poised to reverse trend as a result of the once-again-cooling (warming) North Atlantic SSTs (which will ultimately lead to a warming (cooling) climate). No conclusion on what exactly causes the NHT is given, just that it strongly coincides with the trends of combined PDO and AMO.”

Marcia Wyatt comment here:

A draft of Wyatt et al (2011) can be read here:

Click to access 1WKT_2012_author_manuscript.pdf

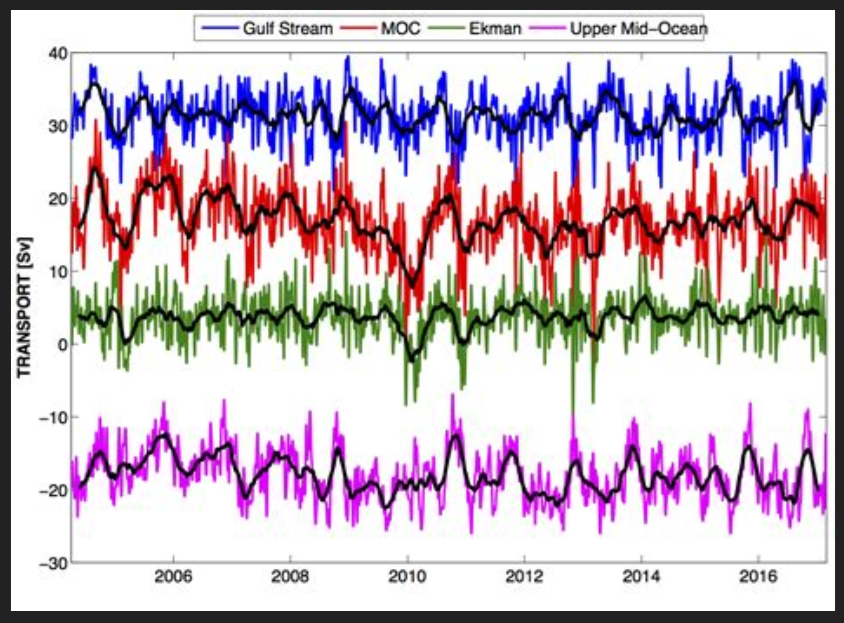

What is the AMOC up to these days?

“We have shown that there was a slowdown in the AMOC transport between 2004 and 2012 amounting to an average of −0.54 Sv yr−1 (95 % c.i. −0.08 to −0.99 Sv yr−1) at 26◦ N, and that this was primarily due to a strengthening of the southward flow in the upper 1100 m and a reduction of the southward transport of NADW below 3000 m. This trend is an order of magnitude larger than that predicted by climate models associated with global climate change scenarios, suggesting that this decrease represents decadal variability in the AMOC system rather than a response to climate change. (lower North Atlantic deep water (LNADW) upper (UNADW) . . .our observations show no significant change in the Gulf Stream transport over the 2004–2012 period when the AMOC is decreasing.”

Click to access os-10-29-2014.pdf

Implications for AMO and Atlantic SSTs

“The poleward transport of heat in the sub-tropical North Atlantic has been shown (Johns et al., 2011) to be highly correlated with the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC). One petawatt (PW = 1015 W) of heat carried by the AMOC is released to the atmosphere between 26◦ N and 50◦ N and has important impacts on the climate of the North Atlantic region (e.g. Srokoz et al., 2012). The AMOC varies on a range of timescales (e.g. Eden and Willebrand, 2001; Kanzow et al., 2010) and is thought to have played a key role in rapid climate change in the past (Ganopolski and Rahmstorf, 2001).”

Click to access Kerr%20Science%2005.pdf

“A speed up (slow down) of the AMOC is in favor of generating a warm (cold) phase of the AMO by the anomalous northward (southward) heat transport in the upper ocean, which reversely leads to a weakening (strengthening) of the AMOC through changes in the meridional density gradient after a delayed time of ocean adjustment. This suggests that on multidecadal timescales the AMO and AMOC are related and interact with each other.”

Click to access Zhang_Wang_JGR2013.pdf

Are we on the cusp of oceanic climate change?

“Sometime after the turn of the century the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation peaked. Due to the volatility of the data and the short time frame, it’s tough to determine when it peaked. But for illustration purposes, Figure 2 compares the same two sea surface temperature data subsets starting in 2003. The surface of the North Atlantic has cooled slightly over that time, while the surfaces of the rest of the global oceans show very little warming.”

New Study Predicts a Slight Cooling of North Atlantic Sea Surface Temperatures over the Next Decade

“The AMO tracks to the solar irradiance with a lag of about 8-9 years. This suggests the current warm AMO state will end by around 2015. Northern Hemispheric temperature will take a leg down. With the cooling of the Pacific now and more La Ninas, look for net cooling especially in the tropics until then.” Joseph D’Aleo

Click to access AMO_Important_in_Northern_Hemispheric_Anomalies.pdf

Update May 19, 2015

Dr. William Gray in his 2012 paper:

“The global surface warming of about 0.7°C that has been experienced over the last 150 years and the multi-decadal up-and-down global temperature changes of 0.3-0.4°C that have been observed over this period are hypothesized to be driven by a combination of multi-century and multi-decadal ocean circulation changes. These ocean changes are due to naturally occurring upper ocean salinity variations. Changes in CO2 play little role in these salinity driven ocean climate forcings. “

A great deal of AMOC explanation is available in Dr. Gray’s paper:

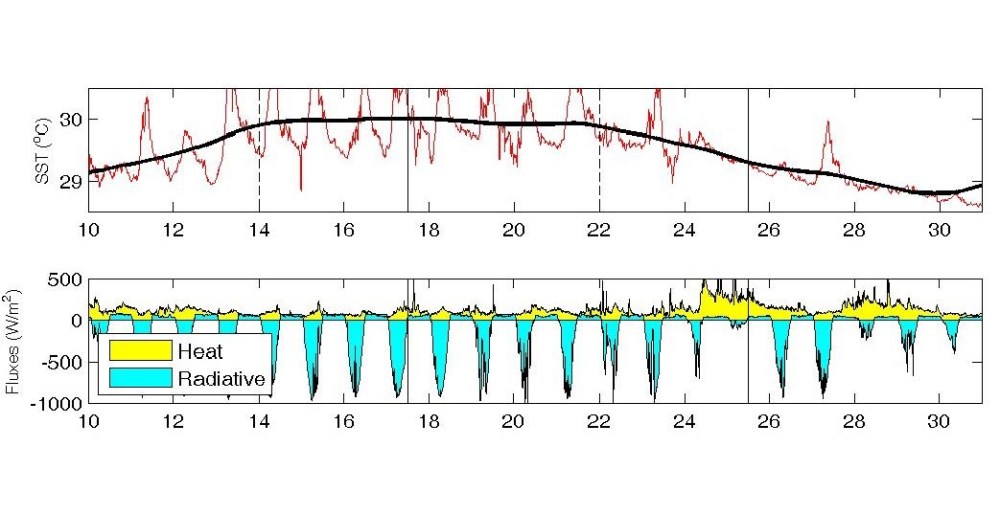

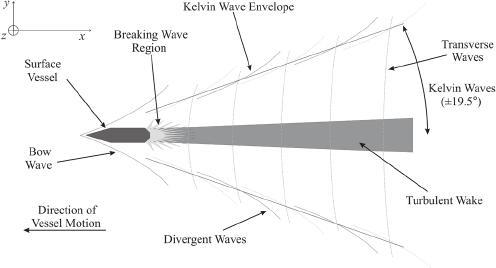

Included are excellent diagrams and charts, such as these: