Perhaps you noticed how public health officials direct the war on coronavirus. The generals obsess over “cases” and “deaths” while hiding numbers of “recoveries” and “cures.” The military paradigm has led pandemic policies seriously astray, as explained by Norman Doidge in his Tablet article Mad Science, Sane Science. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

There are more reasonable approaches to science and COVID-19 than the ‘eradication’ mentality that we lean on.

One cannot underestimate the extent to which modern medicine took up Bacon’s military metaphor of conquest and applied it to itself. This involved rejecting the ancient Hippocratic idea of healing, which—being part of that Greek worldview that saw us as of nature, and not against it—saw the physician as trying to work in alliance with nature, the patient (mind and body and spirit) and the patient’s family. But by the mid-1600s Thomas Sydenham, who became known as the “English Hippocrates,” saw medicine in a new way: “I attack the enemy within by means of cathartics and refrigerants, and by means of a diet”; he wrote, “a murderous array of disease has to be fought against, and the battle is not a battle for the sluggard …” Little has changed since. We see ourselves as engaged in endless wars: “The war against the virus,” “the war against cancer,” or against AIDS, “the war on drugs,” the “battle against heart disease,” we “combat” Alzheimer’s, and so on. As modern physicians came to see themselves as warriors and disease as “the enemy,” treatments became “weapons,” and drugs went from being healing potions to “magic bullets” and vaccines became “shots.”

We combat the enemy with “doctor’s orders,” from the medical “armamentarium,” or “arsenal” as we physicians call our bag of therapeutic tricks.

This military metaphor in medicine gives rise to a mentality that esteems invasive high-tech treatments as somehow more serious than less invasive ones—any collateral damage be damned. Of course, there is a time for a martial attitude in medicine, as, say, in emergencies: If a blood vessel in the brain bursts, the patient needs invasive surgery and a neurosurgeon with nerves of steel, to operate. But there are times when it sets us back. Today, rather than work with the patient as a key ally, we physicians often barely have time to listen to him or her speak. In this metaphor, the patient’s body is less an ally than the battlefield, and the patient is rendered passive, a helpless bystander, as he watches the confrontation that will determine his fate between the two great antagonists, the doctor (plus the scientific research establishment) and the disease (or pathogen). And of course, in the “war against the virus,” it is total “eradication” of such an enemy that is the goal. That, it would seem to us, Bacon’s offspring, as the only sensible approach.

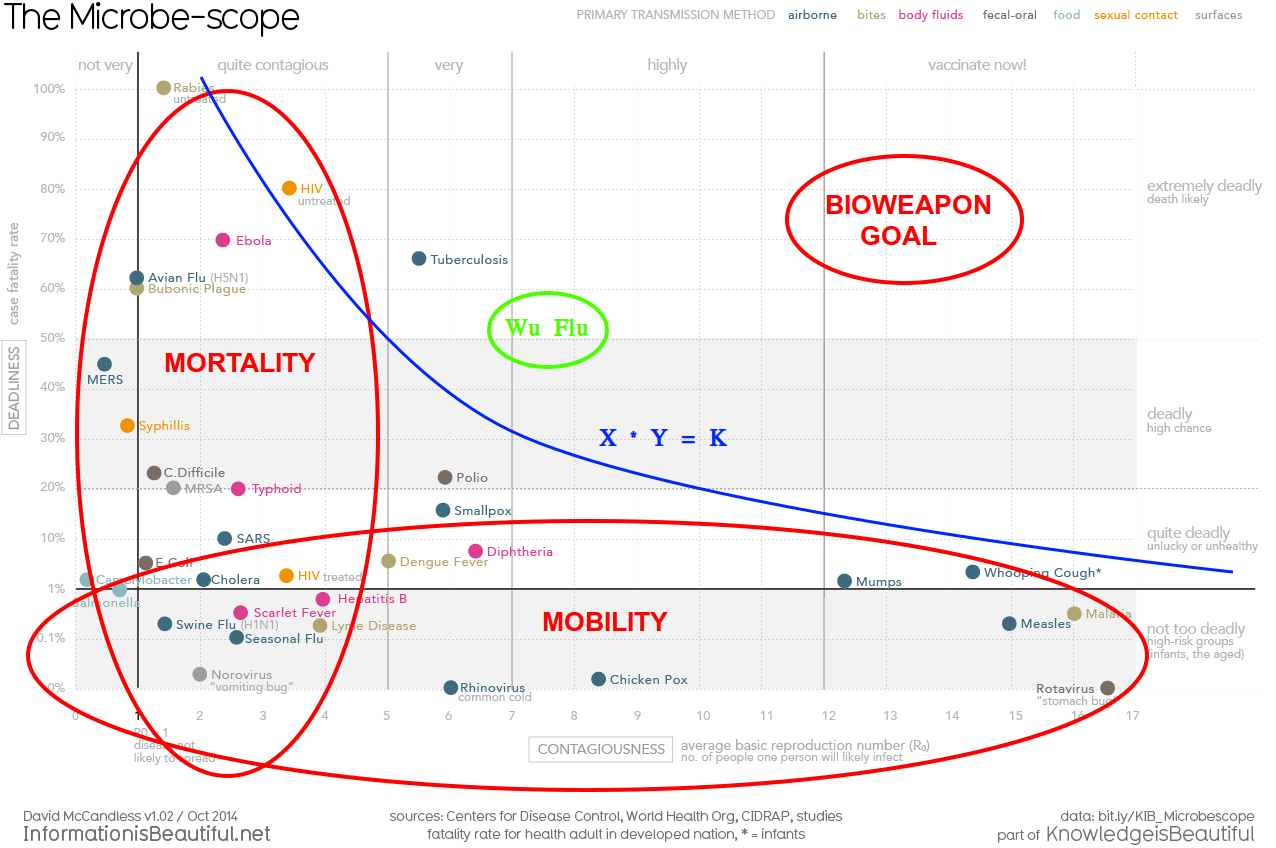

As it turns out, so much of what ails us today are products of modern science and technology gone wild: lethal antibiotic-resistant organisms that our “total eradication of disease mentality” produced because we vastly overused the antibiotics we had (which, by the way, were originally natural products of nature, not the lab); pollution (of every element), chemicals in our baby food, toys, floors, and mattresses causing skyrocketing childhood illnesses; bioterrorism; loss of biodiversity affecting the food chain; fabulous totalitarian surveillance tools called cellphones, global networks that allow our enemies thousands of miles away to reach into the controls of our electrical grids, water systems, food delivery systems, banks, nuclear systems, computers, and control them, turning them on and off with a keystroke; 3D printers to make assault weapons in the basement, nuclear weapons to empower lunatics, industrialized death camps with cyanide showers, and, not to mention man-made environmental disruptions causing ecological catastrophes.

On this list of course, is also a pandemic that spread so rapidly because of air travel, and the “efficient” design of our urban centers which maximize overcrowding—and a microbe that may have originated in a lab known to be unsafe, and experimenting with bat viruses. “Just last year,” an article in Newsweek reported, “the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the organization led by Dr. Fauci, funded scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and other institutions for work on gain-of-function research on bat coronaviruses.”

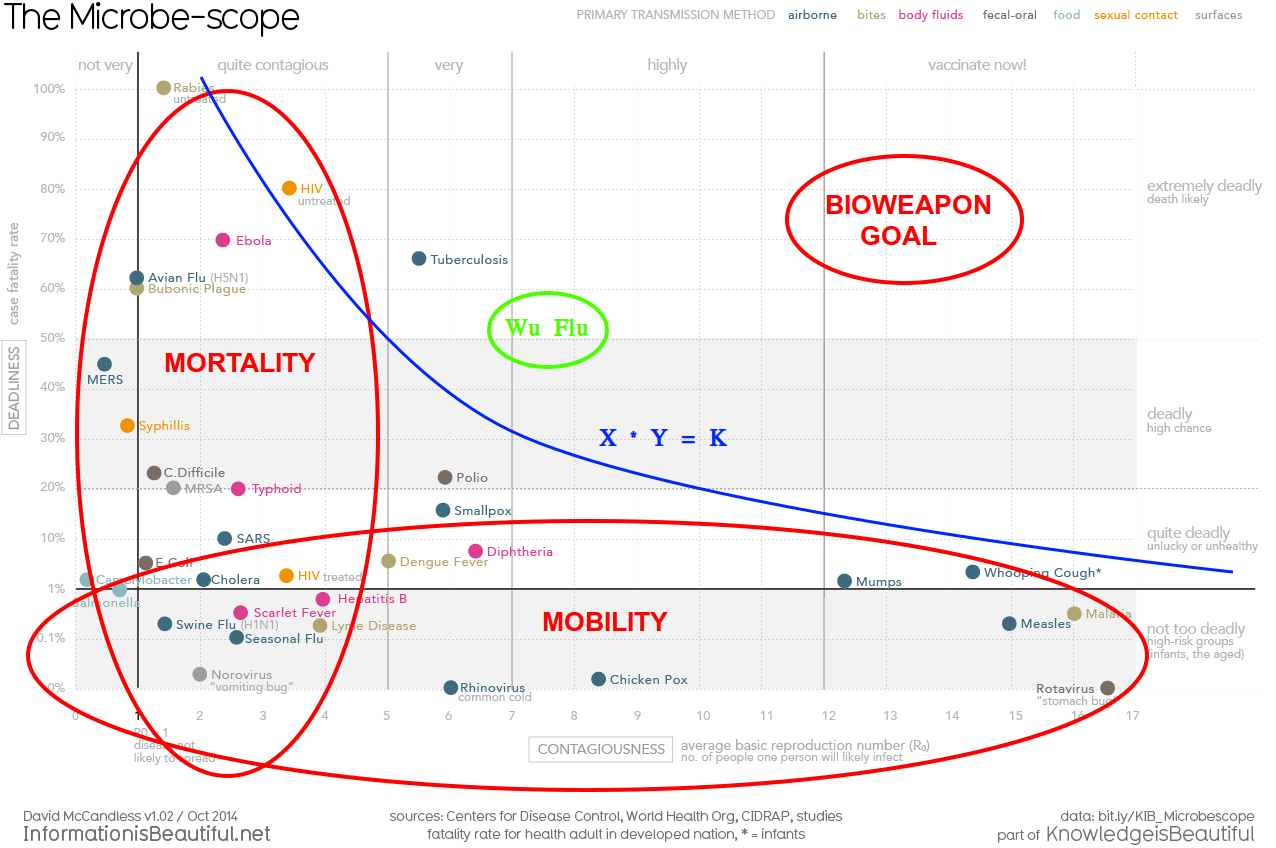

“Gain-of-function research” in this case means augmenting the virus’s contagiousness, and even lethality for the purpose of getting a head start on developing therapeutics or vaccines should it mutate in that direction. Such research is also the meat and potatoes germ-warfare research.. . . Whether or not Wuhan’s gain-of-function work involved creating an artificially enhanced coronavirus has been made almost impossible for outsiders to ascertain, because that lab’s government conveniently insisted it destroy its virus samples and records before an outside investigation could be done.

We are so reliably surprised and caught off guard by the unforeseen consequences of our technologies, and there are now so many serious cases of “science going wrong,” that it might be argued that, in practice, modern science (and the tech it produces) seems to be a machine designed to generate and maximize unintended consequences. And is hence, along with being powerful, also, quite often, ridiculous.

All of this is relevant to the current pandemic. In a way, there are three grand “strategies” to deal with a pandemic. But only one of them indulges the more lunatic strains of military metaphor in medicine.

- The first strategy is never let it in.

- The second, the approach most widely used at present, is to go to rather blunt lockdowns, while we develop therapeutics and vaccines to eradicate the virus.

- The third is to resist lockdowns whenever possible, and instead focus on more differentiated measures than total societal closures, again while we develop therapeutics and vaccines to eradicate the virus.

If the virus doesn’t get in, people are not dying, there isn’t talk of eradication and the military metaphor isn’t used. That strategy has worked so far in Nauru, an island speck, in the paradise of Oceania, a country that is isolated, and small enough to walk across and around in one day, and which, along with Oceania’s Tuvalu, is tied for the record as being the least visited country in the world.

Even the relatively isolated, double-island paradise of New Zealand, was still too connected with the rest of the world to keep the virus out. When it did arrive there, New Zealand tried the second strategy, to eradicate it with a blunt lockdown.

The military metaphors began. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern set the goal of “complete elimination of the virus.” France’s President Emmanuel Macron said, “We are at war … The enemy is there—invisible, elusive—and it is advancing.” Donald Trump described himself as “a wartime president.” War requires emergency measures, which require emergency powers, which demand the immediate suspension of civil liberties—with executives not bothering to go to legislatures because the enemy is coming at us “in waves,” and “surges,” is “killing us in droves.” We “hunker in our bunkers”—in total lockdown. Home’s the only place that’s safe. We must “mobilize” all society in immobility. Punish those who disobey orders. We do it, too, for the health care workers, the heroes on “the frontline,” who risked their lives.

But these undeniable similarities do not mean that medicine is war, any more than war is healing.

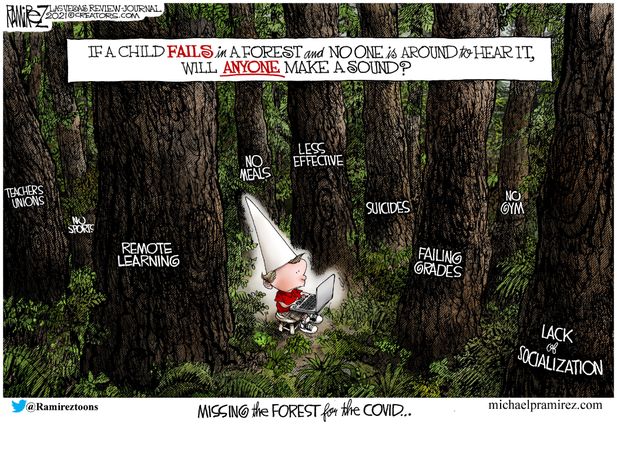

Perhaps the biggest problem with the military metaphor, is how it causes us to narrow our focus almost exclusively on “eradicating the virus,” and “cases of the infected.” This causes us to miss other important ways of dealing with it, that might help us survive it. Public health officials in the “the eradication mode” almost never mention how we can boost our immune systems with vitamins D and C, and zinc, exercise and weight loss. Not their focus. And the narrow focus on eradicating the virus is now causing serious “collateral” harm and death.

But it was not maliciousness but rather the virus eradication mindset that has caused much of the harm. That mindset has led many politicians, and also public health officials, to become oblivious to the death, illness, and devastation that have resulted from the lockdowns. Tedros’ own language speaks this obliviousness, when he says he knows people are “understandably frustrated with being confined to their homes” as though “frustration” is the extent of the problem. What is actually happening is that people’s worlds are collapsing. Fauci early on called the lockdown measure “inconvenient.”

Tedros and other lockdown supporters are almost all themselves employed, and working comfortably, many from home.

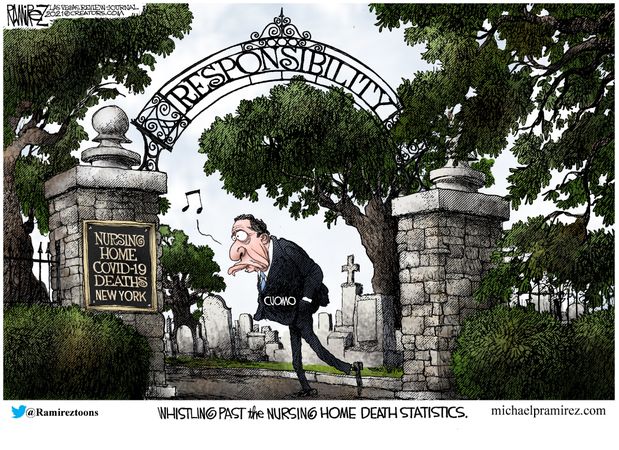

They are part of a class that has government, bureaucratic, educational, media, and corporate salaries, or are in Big Tech, which thrives in lockdown. With an often staggering indifference, they gloss over that fact that the measures they recommend “for all of us” are devastating to those working-class people, the poor, and small-business owners who are losing or have already lost their life savings, health insurance, health, and who are at risk of, or who have already been evicted from their apartments. By September we knew that nearly 60% of (mostly small) businesses that had been forced to close in lockdown were destroyed so their workers would have no jobs to return to. Many more have gone under since. They were closed by often illegal edicts, that left their large corporate competitors like Costco and Walmart open. Thus, instead of going to small widely separated community stores, that admitted a few at a time, people crowded into a few stores without social distancing—the complete reverse of a sensible, scientifically based policy. How did public health officials get away with destroying small business? This is war! Ignore that a meta-analysis of 10 countries and their regions, shows that during last spring, stringent stay and home and business closures did no better in slowing the virus than those that rely on voluntary measures (such as hand washing, social distancing, discouraging travel and large gatherings, successful case tracking, and testing). Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s own latest scientific statistics confirm that 74% of all New York COVID-19 transmission comes from indoor gatherings in private homes, and only 1.4% from in-restaurant dining (all set up for COVID now). The commander in chief says no to indoor restaurant dining in December. Now, even the WHO, which supported lockdowns, is claiming that closed Western economies are devastating poorer countries that are trading partners, and its special envoy for COVID-19, Dr. David Nabarro, has said the WHO anticipates a doubling of world poverty and a doubling of childhood malnutrition because of lockdowns.

The officials, blinded by the eradication at all costs mentality, discarded the practical wisdom required to respond to such a crisis, and endorsed an intervention that defies the standard public health practice of taking a holistic approach and always taking into account a measure’s total effects, and not just its immediate effects on the pathogen labeled as “the invisible enemy.”

“COVID denial” is real. So is “COVID-management-induced-devastation denial.”

What does a scientific approach look like, one that takes the best of our modern instruments that Bacon helped to facilitate, but which does not get us tangled up in the military metaphor, or make delusional attempts to artificially cut us off from the rest of nature?

That would be the approach of Janelle Ayres, Ph.D., a brilliantly original and constructive molecular and systems physiologist, and expert in both immunology and evolution, who heads two labs affiliated with the Salk Institute. Ayres’ work opens up a radically different approach to infectious disease—radical in the original sense of the word, meaning having to do with the root, i.e., the broader biological foundations of infectious disease and health in the “biome,” the sphere of living organisms in which we dwell, and which dwell within us. Thus, to my mind, her work has echoes with some of the ancient insights and intuitions about biological interconnectedness, though I’ve not seen her make this claim.

Ayres’ work is helping us reconceive our relationship to microbial organisms, including pathogens, and showing how they can, for instance, influence our evolution, and we theirs, and it gives us a much more detailed picture of how we actually survive serious infections. She happens to have written one of the best articles ever on COVID-19, that shows a breadth and depth of biological comprehension that is extremely rare among modern scientists who are often specialists in very circumscribed areas, who analyze things into ever smaller parts, and know an incredible amount about incredibly little. Ayres is both a first-rank specialist, and a big-think generalist.

She says, “The way we have been thinking about treating infectious diseases is that we have to annihilate the pathogens through vaccines and antimicrobials.” She completely reframes the problem, and challenges our thinking:

“Instead of asking how do we fight infections, we should be asking ‘how do we survive infections?’”

Changing that single word—“fight” to “survive”—transforms everything. Consider, for example, that new organisms, and strains are evolving all the time. A new coronavirus strain identified in December is said to be 70% more transmissible. Some new strains may be resistant to our existing vaccines and antivirals. Developing different antibiotics or vaccines to eradicate each of them, is not always possible, and when it is, generally takes a long time, and costs a fortune. But if, as is often the case, death is caused by our bodies’ own reactions to the infection, reactions which are very similar, regardless of the pathogen that caused them, learning to block the body from going into overdrive should help people survive multiple infections. As well, there is no reason to believe this approach will cause antibiotic-resistant, antiviral-resistant, or vaccine-resistant strains, because it is not targeting the pathogen per se.

In cooperative co-evolution, there is an incentive for us (or any infested animal) to develop methods to both prevent collateral damage to ourselves, as well as fix it when it occurs. That is the essence of the tolerance system. What Ayres and her colleagues are doing is describing these mechanisms—in minute molecular detail—in the body, and learning to read how organisms that are co-evolving with their hosts are communicating with them—sending signals back and forth. Ideally, the lab would ultimately learn how to use this information to enhance co-evolution in some way, to treat disease.

Ayres’ approach to COVID is not to minimize other approaches but point out that “if we can step beyond our focus on the virus,” there is much more we can learn. For instance, it was assumed early in the pandemic, that severe cases were caused by high viral load, and now we know it is the secondary collateral damage caused by our bodies that is the real killer.

Fewer and fewer medical schools now require the graduating physician to take the ancient Hippocratic oath, the first recorded articulation of medical ethics, that sanctified medical confidentiality and the idea that the doctor worked for his or her patient, and not a third party. How sad, how telling.

It is the same Hippocrates, who boiled all medicine down to two principles in his Epidemics Book I, “Practice two things in your dealing with disease: either help or do not harm the patient.”

And, in this light—of doing no harm, or at least far less—we might remember that we are part of nature, depend on it, it lives in us, and we have links to parts we think remote from us, that we often cannot even see. We might consider setting aside the utopian dream that always becomes a nightmare, because all too often we can’t conquer nature without conquering ourselves.

See Also:

The Virus Wars

Rx for Covid-fighting Politicians

Twelve Forgotten Principles of Public Health