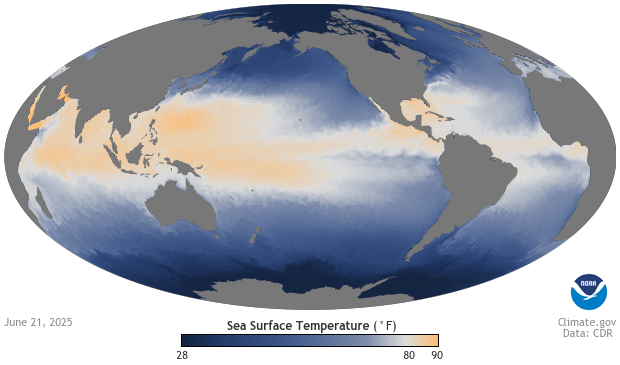

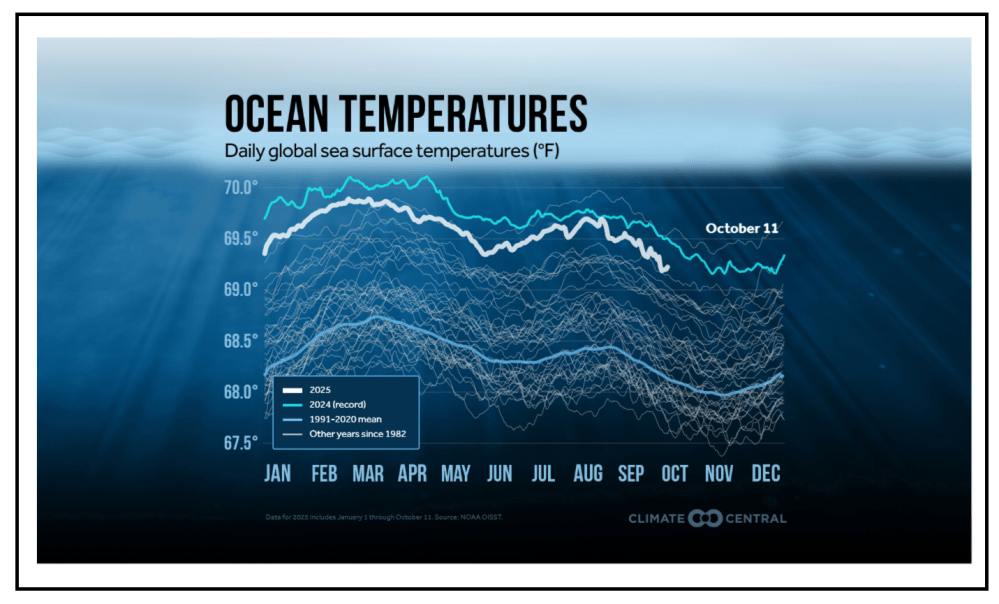

If you watch legacy media, you must also be wondering after seeing all the current headlines about Marine Heat Waves raising the ocean to its boiling point.

Ocean heatwaves are breaking Earth’s hidden climate engine, Science Daily

The Pacific Ocean is overheated, making fall feel like summer, CBC

The ‘blob’ is back — except this time it stretches across the entire north Pacific, CNN

Record marine heatwaves may signal a permanent shift in the oceans, New Scientist

Global warming drives a threefold increase in persistence and 1 °C rise in intensity of marine heatwaves, PNAS

Etc., etc. etc.

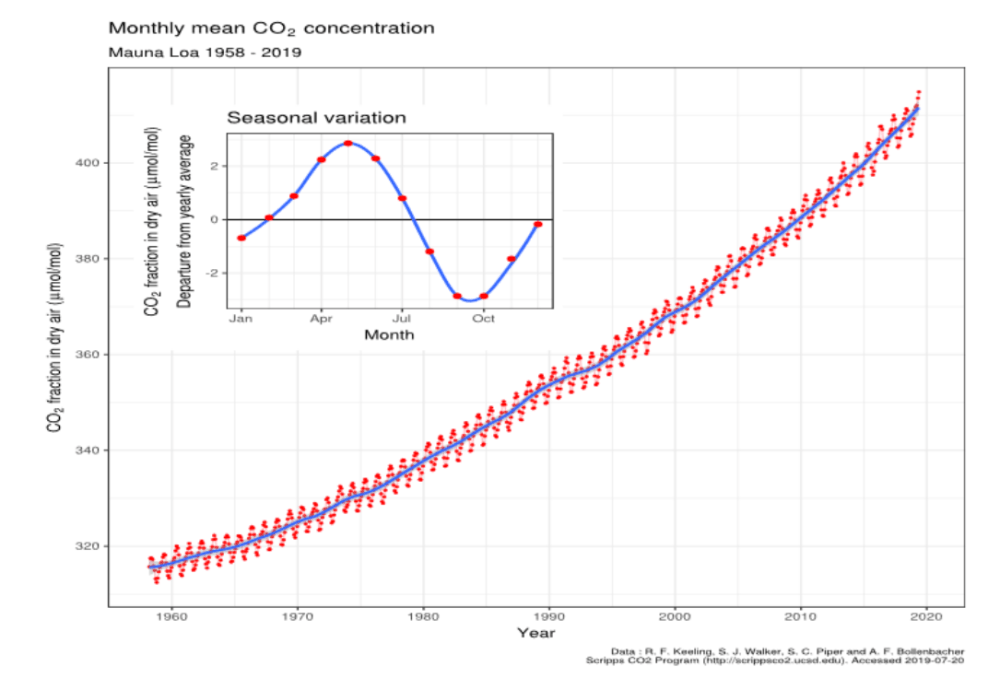

The last one is the paper driving this recent clamor over Ocean SSTs Marcos et al. 2025 From the abstract:

We determine that global warming is responsible for nearly half of these extreme events and that, on a global average, it has led to a three-fold increase in the number of days per year that the oceans experience extreme surface heat conditions. We also show that global warming is responsible for an increase of 1 °C in the maximum intensity of the events. Our findings highlight the detrimental role that human-induced global warming plays on marine heatwaves. This study supports the need for mitigation and adaptation strategies to address these threats to marine ecosystems.

The coordinated media reports are exposed by all of them containing virtually the same claim:

As climate change causes our planet to warm, marine heatwaves are

becoming more frequent, more intense, and longer lasting.

Animation shows locations of moderate to severe MHWs mid-month 2025 January to October. A marine heatwave is defined as one where the measured temperature is within 10% of the maximum values observed (i.e., above the Threshold (90th quantile) , for at least 5 consecutive days. For this, the intensity is compared to the difference between the climatological mean and the 90th percentile value (threshold). A marine heatwave intensity between 1 and 2 times this difference corresponds to a heatwave of moderate category; between 2 and 3 times, to a strong category; between 3 and 4 times, to a severe category; and a difference greater than 4 times corresponds to an extreme category.

First some background context on the phenomena (in italics with my bolds).

Background from perplexity.ai How Do Warm and Cool Ocean Blobs Circulate?

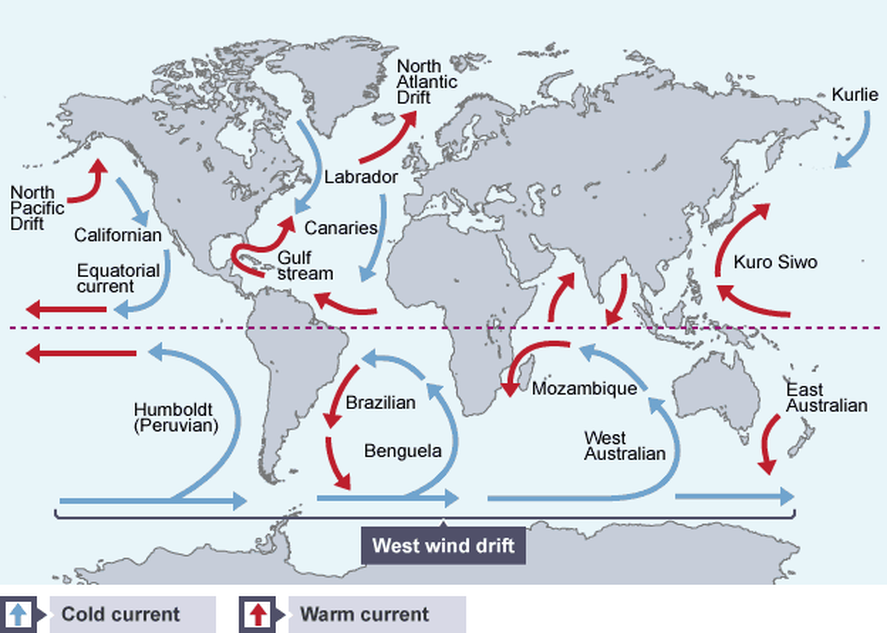

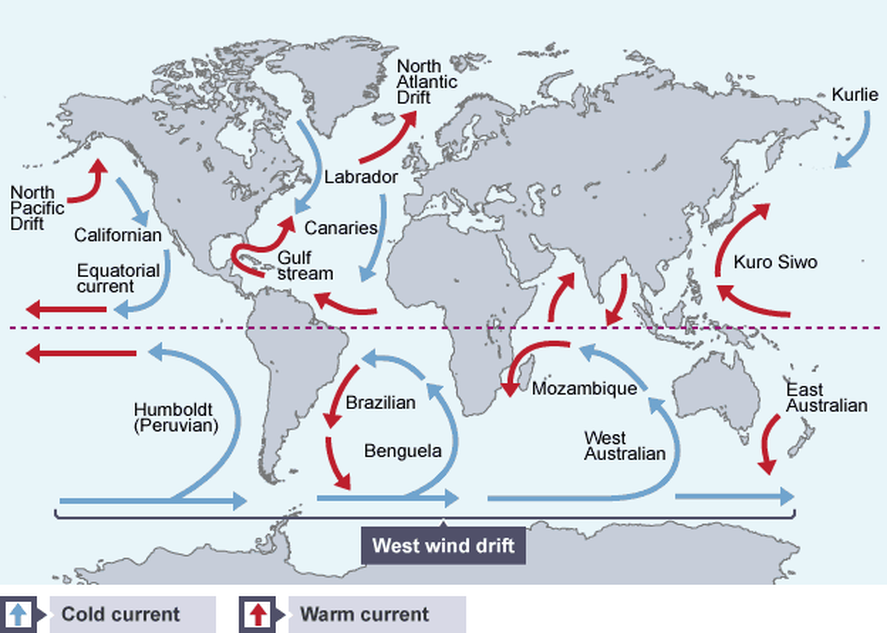

Warm and cool ocean blobs circulate through distinct oceanic and atmospheric processes, often linked to major currents and atmospheric patterns.

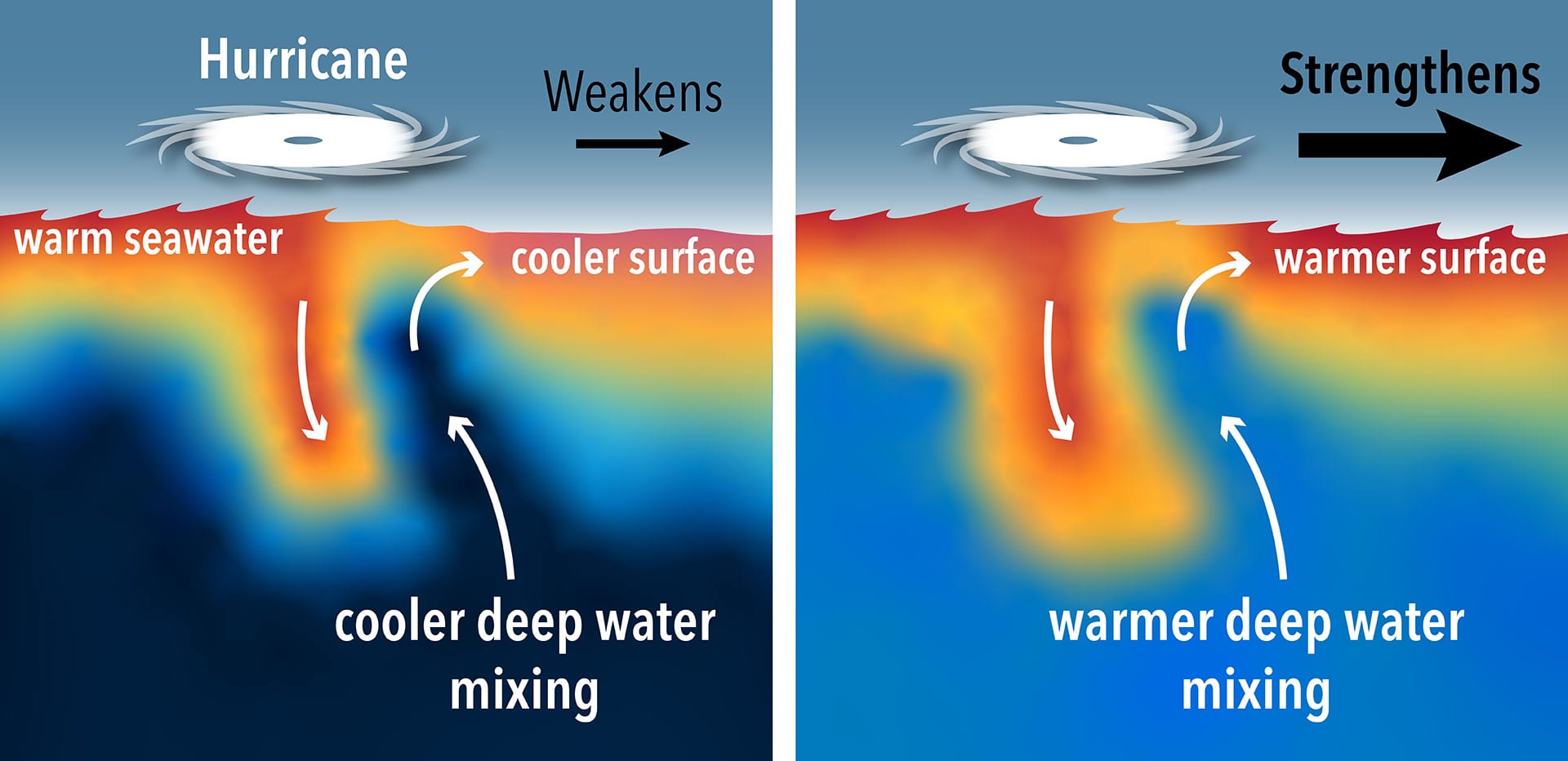

Warm ocean blobs, such as the “warm blob” in the northeast Pacific, form due to atmospheric circulation changes triggered by factors like Arctic warming. This leads to a high-pressure system over the region, weakening westerly winds and reducing ocean heat loss, causing surface waters to warm and creating persistent warm anomalies. The formation of these warm blobs involves a feedback loop between weakened winds, reduced ocean-atmosphere heat exchange, and ocean circulation, which retains heat in the mixed layer of the ocean.

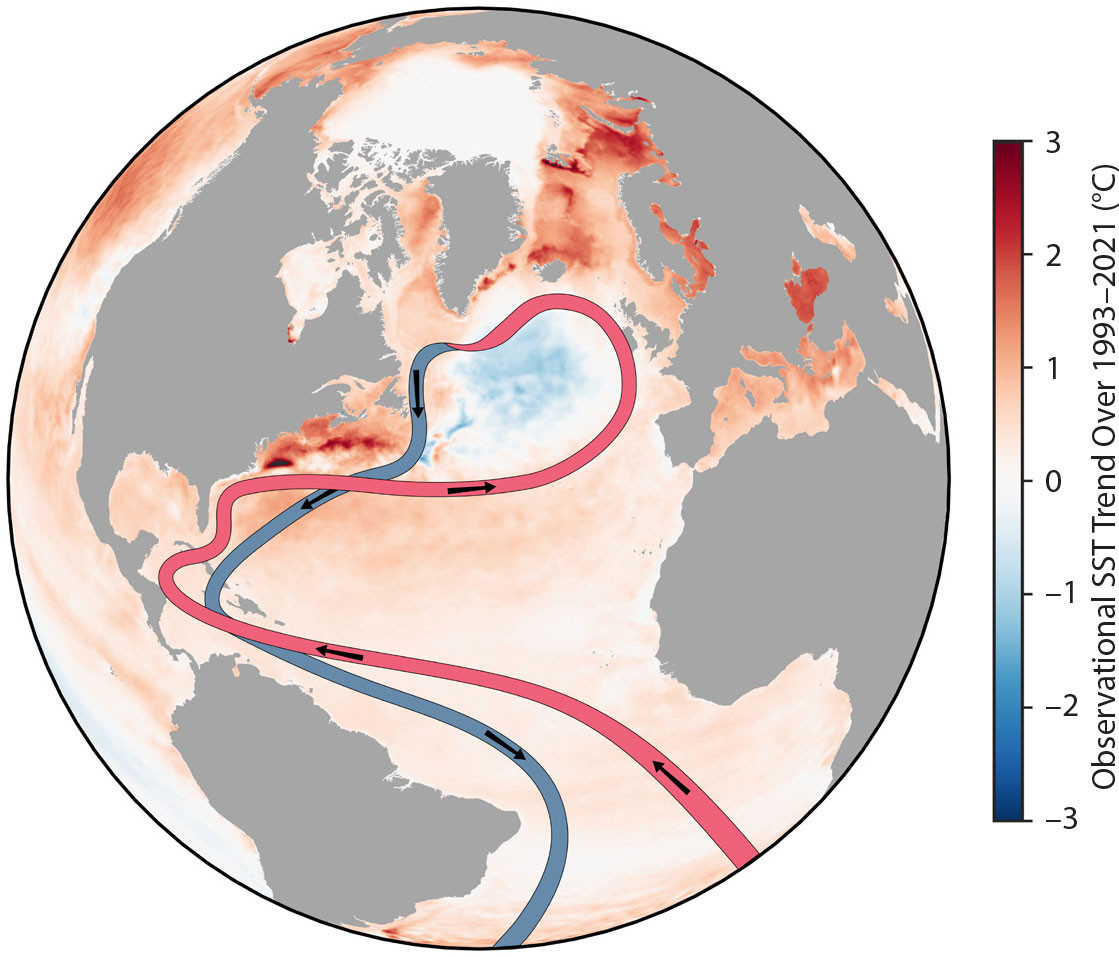

Cool ocean blobs, like the North Atlantic “cold blob,” are influenced by weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). This circulation moves warm, salty water northward, which cools, sinks, and then the cooler deep water travels southward in a conveyor-belt style flow. The cold blob forms when excess freshwater from ice melt dilutes the salty water, reducing its density and sinking ability, weakening this circulation and causing cooler surface water to persist. This cooling also affects the atmosphere by reducing water vapor, which decreases greenhouse effect locally and amplifies the cold anomaly, creating a coupled ocean-atmosphere feedback loop.

In summary, warm and cool ocean blobs circulate through a combination of ocean current dynamics and atmospheric interactions. Warm blobs form where atmospheric changes reduce ocean heat loss and circulation shifts retain heat, while cool blobs occur where circulation weakens, allowing cooler, less dense waters to persist and affect atmospheric conditions as well.

Then a summary of the issues undermining the alarmists’ claim.

From perplexity.ai What are reasons to doubt climate change is increasing marine heatwaves?

There are several reasons to doubt that climate change is definitively increasing the frequency, intensity, duration, and spatial extent of marine heatwaves, based on some ongoing scientific debates and uncertainties.

Natural Variability and Other Factors

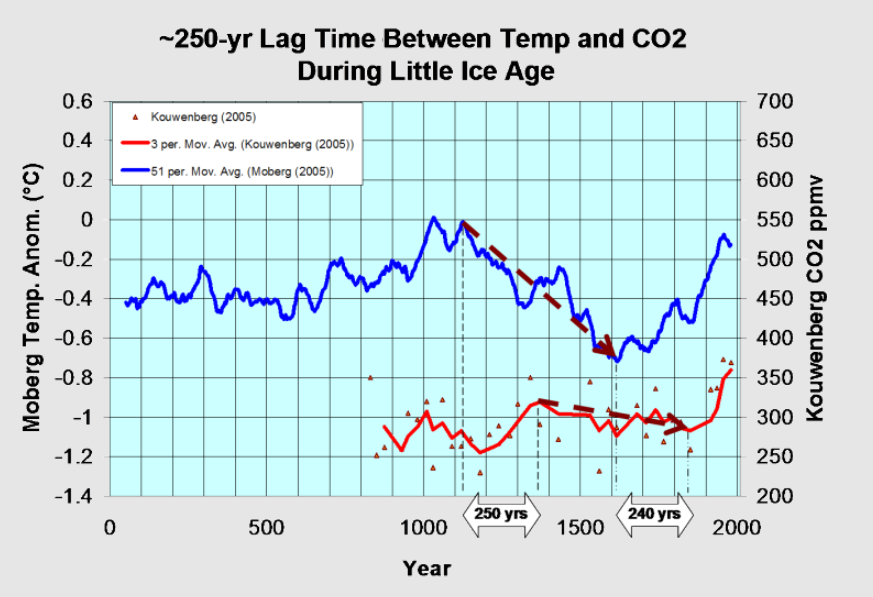

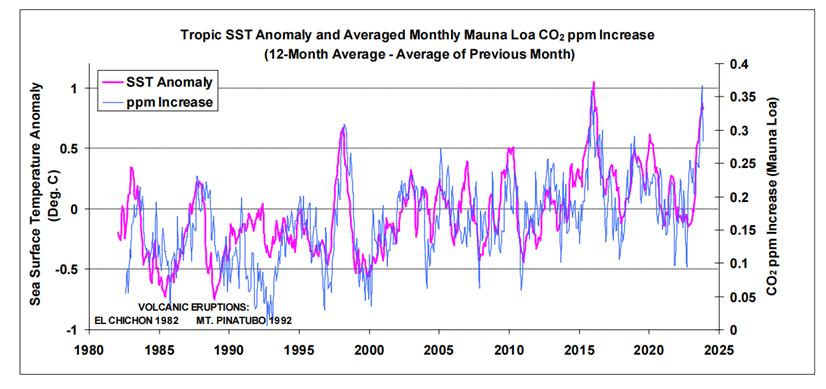

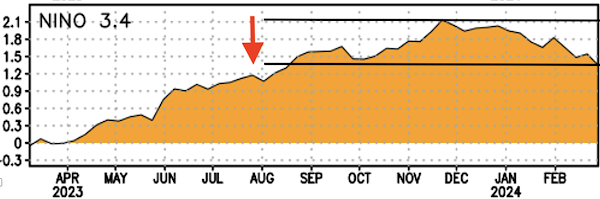

♦ Marine heatwaves are influenced by natural climate variability, such as El Niño, Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and other oceanic and atmospheric processes. These phenomena can cause fluctuations in sea surface temperatures independent of long-term climate change, leading to periods of warmer ocean conditions that may be mistaken for climate-driven trends.

♦ Some studies emphasize the role of internal ocean variability, which can cause significant short-term temperature anomalies without requiring a direct link to anthropogenic climate change.

Complexity of Attribution

♦ The attribution of marine heatwave trends specifically to climate change involves complex modeling and statistical analysis, which can have uncertainties. Certain models suggest that long-term temperature increases are the primary driver, but the contribution of natural variability remains significant and sometimes difficult to separate clearly from climate signals.

♦ Regional differences and localized oceanic processes can obscure the global patterns, leading some scientists to argue that not all observed phenomena are directly attributable to climate change, particularly in areas with strong natural variability.

Limitations of Climate Models

♦ Climate models predicting future marine heatwave conditions depend heavily on assumptions about greenhouse gas emissions and other factors. These models often have limitations in resolution and in capturing small-scale processes, which could lead to overestimations or underestimations of climate change impacts.

Data Gaps and Uncertainties

♦ Although current observations show increasing trends in marine heatwaves, data gaps exist, especially in remote or deep-sea regions, making comprehensive global assessments challenging. These gaps contribute to uncertainty regarding the full extent and causality of observed changes.

♦ The precise long-term ecological impacts and possible adaptation or resilience mechanisms of marine ecosystems also remain uncertain, complicating the understanding of climate change’s role versus natural variability.

Summary

While a considerable body of evidence supports the role of climate change in increasing marine heatwaves, skepticism persists due to the influence of natural variability, model limitations, regional differences, and data gaps. These factors suggest that attribution is complex, and ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of the relative contributions of human influences and natural climate fluctuations.

Finally, a discussion of a specific example revealing flawed methods supposedly connecting CO2 emissions to marine heatwaves.

Much Ado About Marine Heat Waves

The promotion of this scare was published in 2022 at Nature by Barkhordarian et al. Recent marine heatwaves in the North Pacific warming pool can be attributed to rising atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases. This post will unpack the reasons to distrust this paper and its claims. First the Abstract of the subject and their declared findings in italics with my bolds.

Abstract

Over the last decade, the northeast Pacific experienced marine heatwaves that caused devastating marine ecological impacts with socioeconomic implications. Here we use two different attribution methods and show that forcing by elevated greenhouse gases levels has virtually certainly caused the multi-year persistent 2019–2021 marine heatwave. There is less than 1% chance that the 2019–2021 event with ~3 years duration and 1.6 ∘C intensity could have happened in the absence of greenhouse gases forcing. We further discover that the recent marine heatwaves are co-located with a systematically-forced outstanding warming pool, which we attribute to forcing by elevated greenhouse gases levels and the recent industrial aerosol-load decrease. The here-detected Pacific long-term warming pool is associated with a strengthening ridge of high-pressure system, which has recently emerged from the natural variability of climate system, indicating that they will provide favorable conditions over the northeast Pacific for even more severe marine heatwave events in the future.

Background on Ocean Warm Pools

Wang and Enfield study is The Tropical Western Hemisphere Warm Pool Abstract in italics with my bolds.

Abstract

The Western Hemisphere warm pool (WHWP) of water warmer than 28.5°C extends from the eastern North Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, and at its peak, overlaps with the tropical North Atlantic. It has a large seasonal cycle and its interannual fluctuations of area and intensity are significant. Surface heat fluxes warm the WHWP through the boreal spring to an annual maximum of SST and areal extent in the late summer/early fall, associated with eastern North Pacific and Atlantic hurricane activities and rainfall from northern South America to the southern tier of the United States. SST and area anomalies occur at high temperatures where small changes can have a large impact on tropical convection. Observations suggest that a positive ocean-atmosphere feedback operating through longwave radiation and associated cloudiness is responsible for the WHWP SST anomalies. Associated with an increase in SST anomalies is a decrease in atmospheric sea level pressure.

Chou and Chou published On the Regulation of the Pacific Warm Pool Temperature:

Abstract

Analyses of data on clouds, winds, and surface heat fluxes show that the transient behavior of basin-wide large-scale circulation has a significant influence on the warm pool sea surface temperature (SST). Trade winds converge to regions of the highest SST in the equatorial western Pacific. The reduced evaporative cooling due to weakened winds exceeds the reduced solar heating due to enhanced cloudiness. The result is a maximum surface heating in the strong convective and high SST regions. The maximum surface heating in strong convective regions is interrupted by transient atmospheric and oceanic circulation. Regions of high SST and low-level convergence follow the Sun. As the Sun moves away from a convective region, the strong trade winds set in, and the evaporative cooling enhances, resulting in a net cooling of the surface. We conclude that the evaporative cooling associated with the seasonal and interannual variations of trade winds is one of the major factors that modulate the SST distribution of the Pacific warm pool.

Comment:

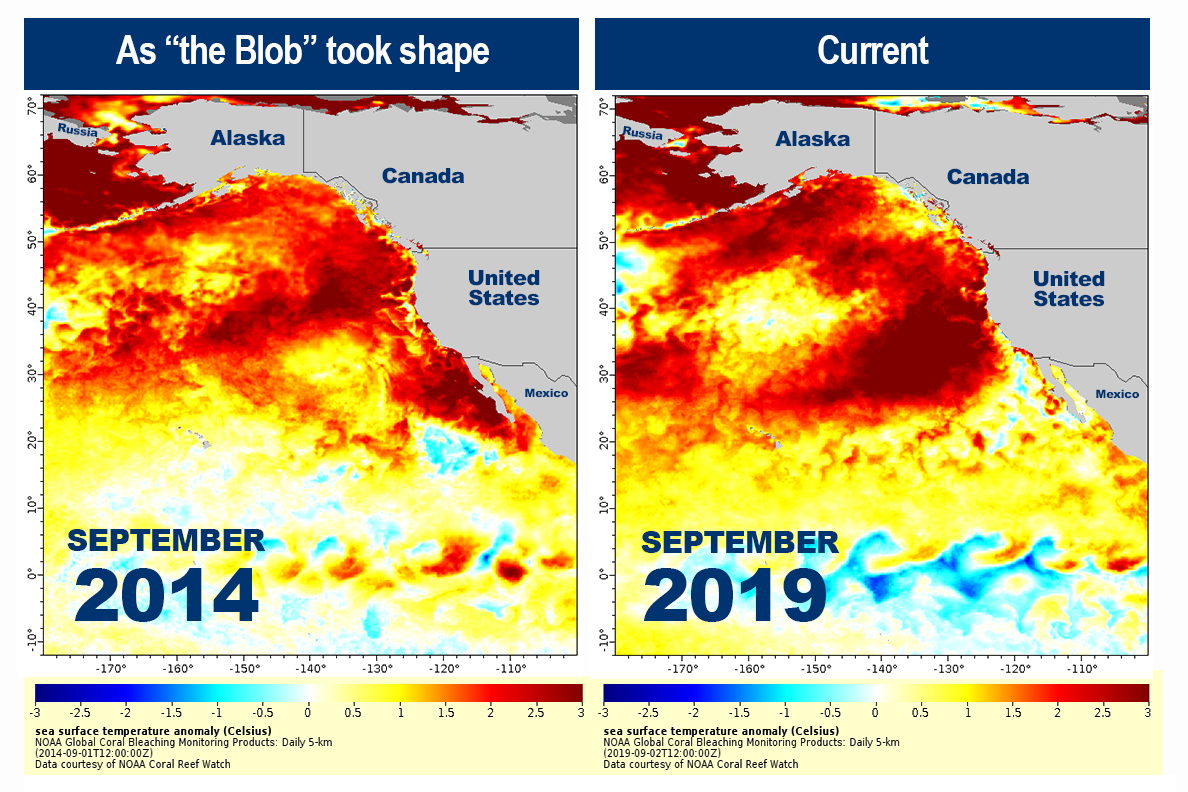

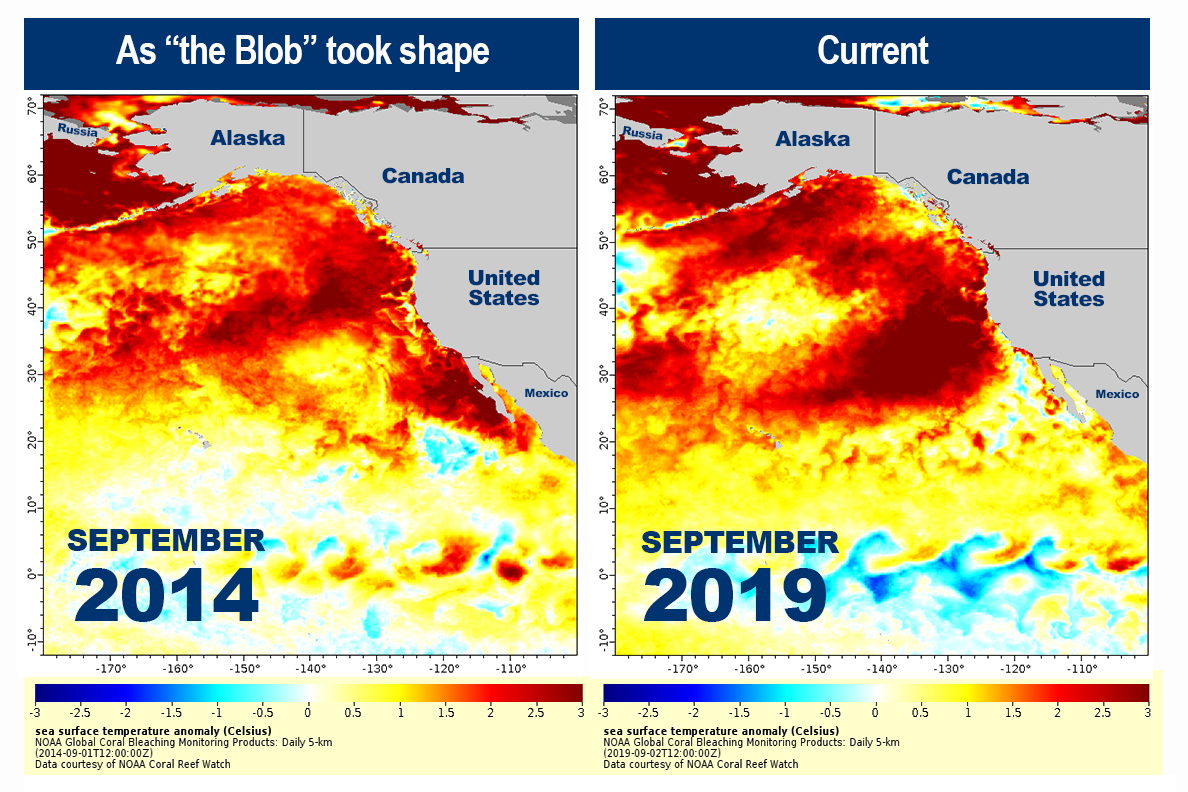

So these are but two examples of oceanographic studies describing natural factors driving the rise and fall of Pacific warm pools. Yet the Nature paper claims rising CO2 from fossil fuels is the causal factor, waving away natural processes. Skeptical responses were already lodged upon the first incidence of the North Pacific marine heat wave, the “Blob” much discussed by west coast US meteorologists. One of the most outspoken against the global warming attributionists has been Cliff Mass of Seattle and University of Washington. Writing in 2014 and 2015, he observed the rise and fall of the warming blob and then posted a critique of attribution attempts at his blog. For example, Media Miscommunication about the Blob. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Blob Media Misinformation

One of the most depressing things for scientists is to see the media misinform the public about an important issue.

During the past few days, an unfortunate example occurred regarding the warm water pool that formed over a year ago in the middle of the north Pacific, a.k.a., the blob. Let me show how this communication failure occurred, with various media outlets messed things up in various ways.

The stimulant for the nationwide coverage of the Blob was a very nice paper published by Nick Bond (UW scientist and State Climatologist), Meghan Cronin, Howard Freeland, and Nathan Mantua in Geophysical Research Letters.

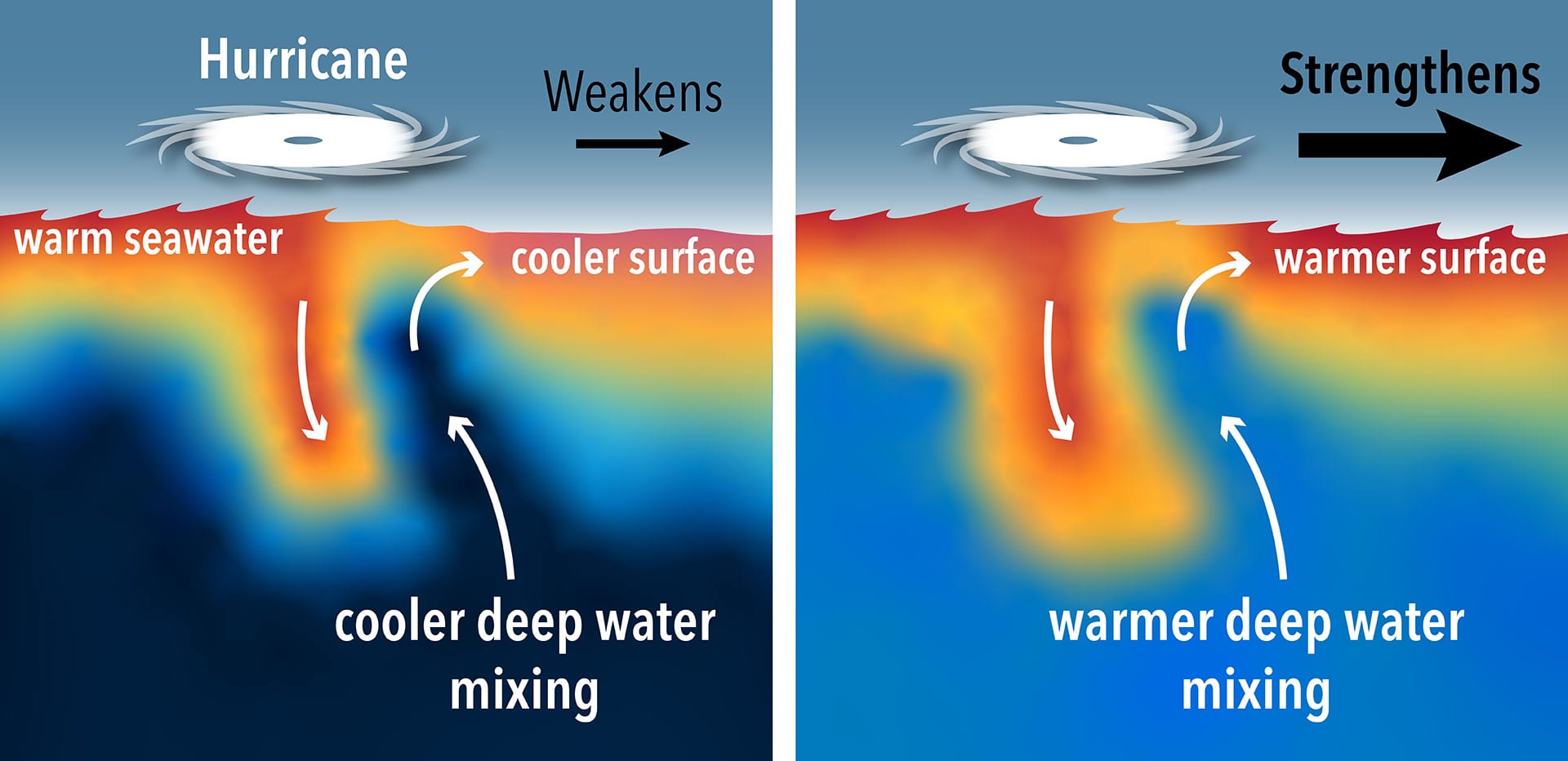

This publication described the origin of the Blob, showing that it was the result of persistent ridging (high pressure) over the Pacific. The high pressure, and associated light winds, resulted in less vertical mixing of the upper layer of the ocean; with less mixing of subsurface cold water to the surface. Furthermore, the high pressure reduced horizontal movement of colder water from the north. Straightforward and convincing work.

The inaccurate press release then led to a media frenzy, with the story going viral. And unfortunately, many of the media got it wrong.

There were two failure modes. In one, the headline was wrong, but the internal story was correct. . . In the second failure mode, the story itself was essentially flawed, with most claiming that the Blob off of western North America was the cause of the anomalous circulation (big ridge over West Coast, trough over the eastern U.S.). (The truth: the Blob was the RESULT of the anomalous circulations.) That the Blob CAUSED the California drought or the cold wave in the eastern U.S. These deceptive stories were found in major outlets around the country, including the Washington Post, NBC News, and others.

Blob Returns, Attribution Misinformation

When the Blob returned 2020-2021, Cliff Mass had cause to again lament how the public is misled. This time misdirection instigated by activist scientists using flawed methods. His post Miscommunication in Recent Climate Attribution Studies. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

This attribution report, and most media stories that covered it, suggested a central role for global warming for the heatwave. As demonstrated in my previous blog, their narrative simply does not hold up to careful examination.

This blog will explain why their basic framing and approach is problematic, leading readers (and most of the media) to incorrect conclusions.

For the heatwave, the attribution folks only examine the statistics of temperatures hitting the record highs (108F in Seattle), but avoid looking at the statistics of temperature exceeding 100F, or even the record highs (like 103F in Seattle). There is a reason they don’t do that. It would tell a dramatically different (and less persuasive) story.

In the attribution studies, the main technology for determining changed odds of extreme weather is to use global climate models. First, they run the models with greenhouse gas forcing (which produces more extreme precipitation and temperature), and then they run the models again without increased greenhouse gases concentrations. By comparing the statistics of the two sets of simulations, they attempt to determine how the odds of extreme precipitation or temperature change.

Unfortunately, there are serious flaws in their approach: climate models fail to produce sufficient natural variability (they underplay the black swans) and their global climate models don’t have enough resolution to correctly simulate critical intense, local precipitation features (from mountain enhancement to thunderstorms). On top of that, they generally use unrealistic greenhouse gas emissions in their models (too much, often using the RCP8.5 extreme emissions scenario) And there is more, but you get the message. ( I am weather/climate modeler, by the way, and know the model deficiencies intimately.)

Vaunted Fingerprinting Attribution Is Statistically Unsound

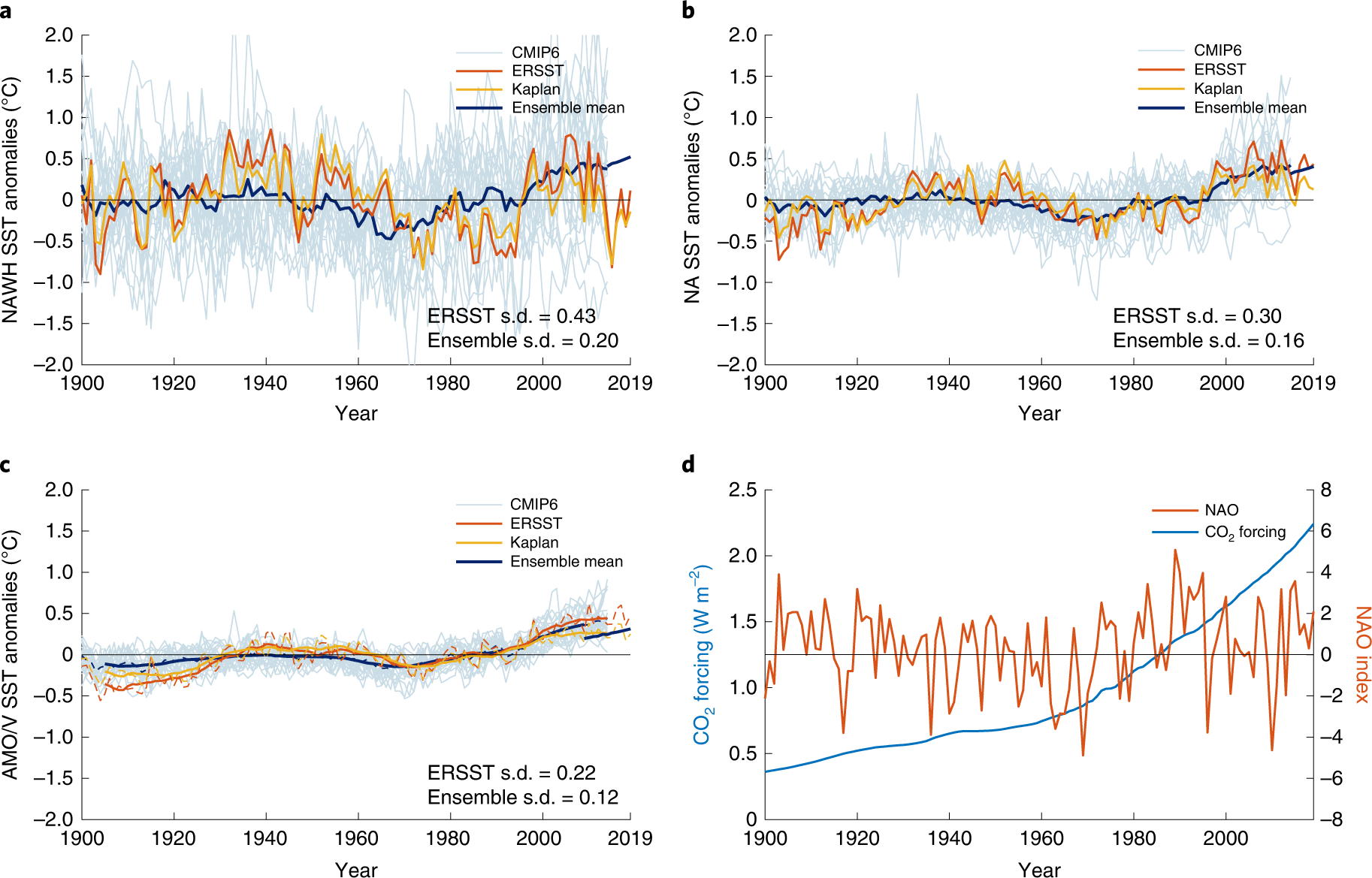

From Barkhordarian et al.

Unlike previous studies which have focused on linking the SST patterns in the North Pacific to changes in the oceanic circulation and the extratropical/tropical teleconnections2,12,17,18,20,24,26, we here perform two different statistical attribution methodologies in order to identify the human fingerprint in Northeast Pacific SST changes both on multidecadal timescale (changes of mean SST) and on extreme SST events on daily timescale (Marine Heatwaves). Evidence that anthropogenic forcing has altered the base state (long-term changes of mean SST) over the northeast Pacific, which is characterized by strong low-frequency SST fluctuations, would increase confidence in the attribution of MHWs27, since rising mean SST is the dominant driver of increasing MHW frequency and intensity, outweighing changes due to temperature variability1,2.

In this study, we provide a quantitative assessment of whether GHG forcing, the main component of anthropogenic forcings, was necessary for the North Pacific high-impact MHWs (the Blob-like SST anomalies) to occur, and whether it is a sufficient cause for such events to continue to repeatedly occur in the future. With these purposes, we use two high-resolution observed SST datasets, along with harnessing two initial-condition large ensembles of coupled general circulation models (CESM1-LE28,29 with 35 members, and MPI-GE30 with 100 members). These large ensembles can provide better estimates of an individual model’s internal variability and response to external forcing31,32, and facilitate the explicit consideration of stochastic uncertainty in attribution results33. We also use multiple single-forcing experiments from the Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparision Project (DAMIP34) component of Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 6 (CMIP635).

From Barkhordarian et al. References

The IPCC’s attribution methodology is fundamentally flawed

The central paper underpinning the attribution analysis was assessed and found unreliable by statistician Ross McKitrick’s published evaluation. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

One day after the IPCC released the AR6 I published a paper in Climate Dynamics showing that their “Optimal Fingerprinting” methodology on which they have long relied for attributing climate change to greenhouse gases is seriously flawed and its results are unreliable and largely meaningless. Some of the errors would be obvious to anyone trained in regression analysis, and the fact that they went unnoticed for 20 years despite the method being so heavily used does not reflect well on climatology as an empirical discipline.

My paper is a critique of “Checking for model consistency in optimal fingerprinting” by Myles Allen and Simon Tett, which was published in Climate Dynamics in 1999 and to which I refer as AT99. Their attribution methodology was instantly embraced and promoted by the IPCC in the 2001 Third Assessment Report (coincident with their embrace and promotion of the Mann hockey stick). The IPCC promotion continues today: see AR6 Section 3.2.1. It has been used in dozens and possibly hundreds of studies over the years. Wherever you begin in the Optimal Fingerprinting literature (example), all paths lead back to AT99, often via Allen and Stott (2003). So its errors and deficiencies matter acutely.

Abstract

Allen and Tett (1999, herein AT99) introduced a Generalized Least Squares (GLS) regression methodology for decomposing patterns of climate change for attribution purposes and proposed the “Residual Consistency Test” (RCT) to check the GLS specification. Their methodology has been widely used and highly influential ever since, in part because subsequent authors have relied upon their claim that their GLS model satisfies the conditions of the Gauss-Markov (GM) Theorem, thereby yielding unbiased and efficient estimators.

But AT99:

- stated the GM Theorem incorrectly, omitting a critical condition altogether,

- their GLS method cannot satisfy the GM conditions, and

- their variance estimator is inconsistent by construction.

- Additionally, they did not formally state the null hypothesis of the RCT nor

- identify which of the GM conditions it tests, nor

- did they prove its distribution and critical values, rendering it uninformative as a specification test.

The continuing influence of AT99 two decades later means these issues should be corrected. I identify 6 conditions needing to be shown for the AT99 method to be valid.”

In Conclusion, McKitrick:

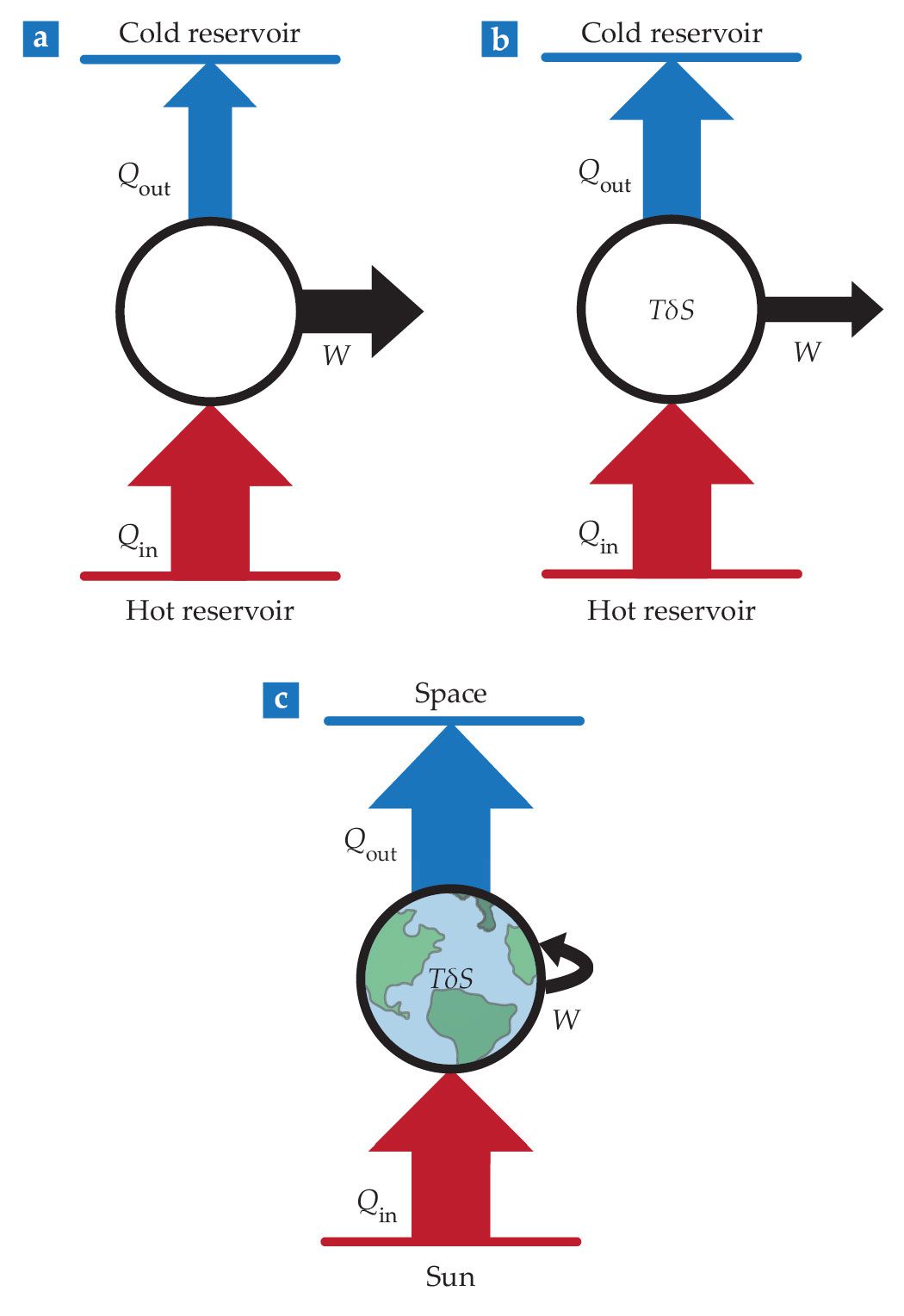

One point I make is that the assumption that an estimator of C provides a valid estimate of the error covariances means the AT99 method cannot be used to test a null hypothesis that greenhouse gases have no effect on the climate. Why not? Because an elementary principle of hypothesis testing is that the distribution of a test statistic under the assumption that the null hypothesis is true cannot be conditional on the null hypothesis being false. The use of a climate model to generate the homoscedasticity weights requires the researcher to assume the weights are a true representation of climate processes and dynamics.

The climate model embeds the assumption that

greenhouse gases have a significant climate impact.

Or, equivalently, that natural processes alone cannot generate a large class of observed events in the climate, whereas greenhouse gases can. It is therefore not possible to use the climate model-generated weights to construct a test of the assumption that natural processes alone could generate the class of observed events in the climate.