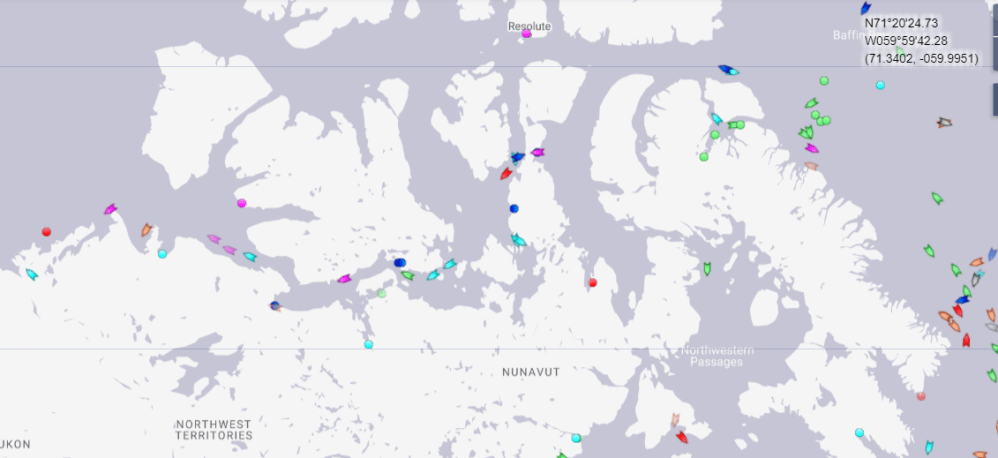

Update on Northwest Passage September 1, 2019

Background information is reprinted later on. Above shows the last two weeks of shifting ice concentrations in the NWP choke point, Queen Maud region. Aug. 19 Prince Regent Inlet, top center was plugged, while Peel Sound, top left opened up and allowed passage. In just a week or so, Prince Regent turned green (<3/10 covered) to blue. At the same time thick ice dissipated in Franklin Strait, center left, opening the way SW. In just the last few days a tongue of thick ice has formed at the extreme top of Peel Sound, obstructing entrance from the north.

Note on the map right edge the reference to Foxe Basin, a body of open water south of Baffin Island. The channel connecting into Gulf of Boothia is blocked most years, but was open in 2016, and passable now. This is an alternate NWP route when Bellot Strait is also open.

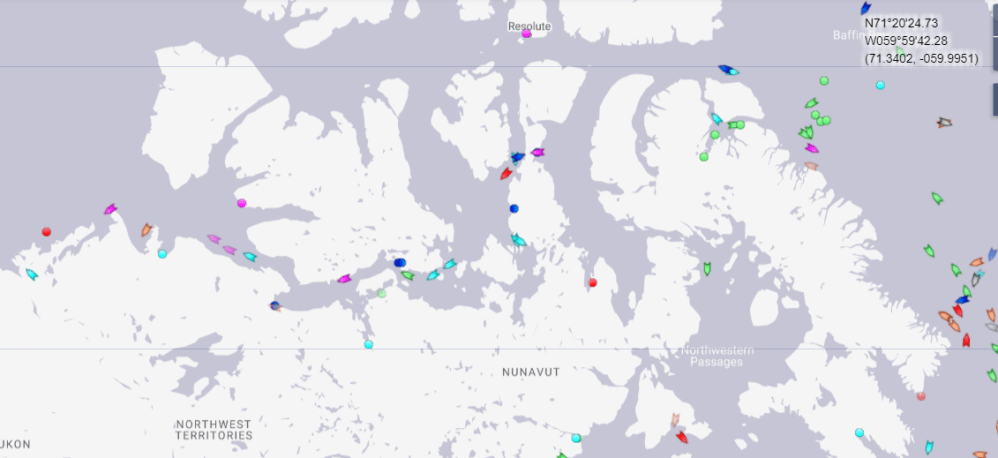

This is today’s map of vessels in the NWP. Cargo ships in green, tugs in cyan, Passenger ships in blue, yachts in purple. Note that Peel Sound was the preferred route earlier, now ships are using Bellot strait.

Less Artic Ice This year

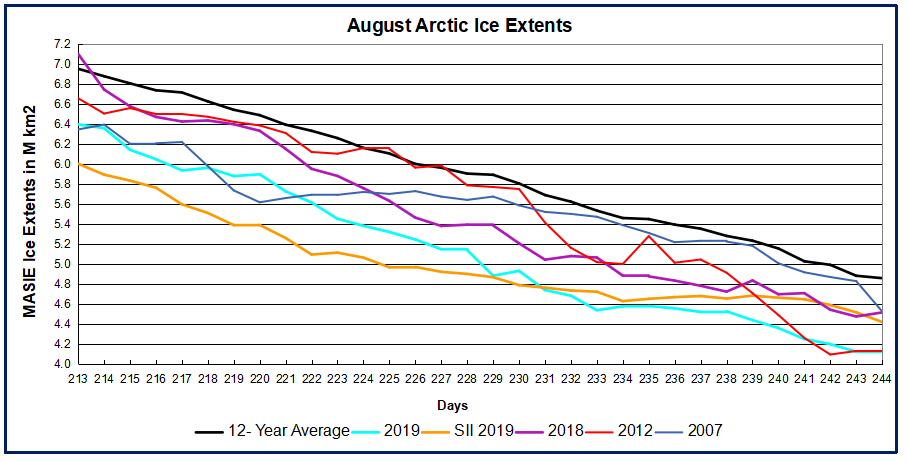

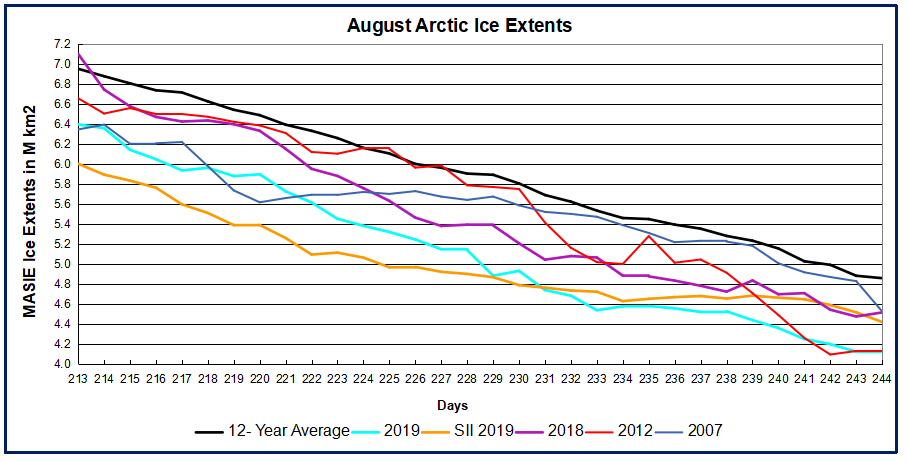

The CAA region (Canadian Arctic Archipelago) shown above has much less ice this year, along with most of the Arctic ocean.

As the graph shows, MASIE ice extent this year is presently as low as 2012, year of the Great Arctic Cyclone. SII is showing about 300k km2 more ice, and matching MASIE 2018 and 2007. All are below the 12 year average at Sept. 1 (day 244). The table below provides the numbers by regions.

| Region |

2019244 |

Day 244 Average |

2019-Ave. |

2018244 |

2019-2018 |

| (0) Northern_Hemisphere |

4113725 |

4857617 |

-743892 |

4514946 |

-401222 |

| (1) Beaufort_Sea |

362877 |

531979 |

-169101 |

529700 |

-166823 |

| (2) Chukchi_Sea |

139335 |

219474 |

-80139 |

178633 |

-39299 |

| (3) East_Siberian_Sea |

96512 |

356347 |

-259835 |

475647 |

-379135 |

| (4) Laptev_Sea |

102556 |

172240 |

-69684 |

21366 |

81190 |

| (5) Kara_Sea |

2479 |

40884 |

-38405 |

235 |

2244 |

| (6) Barents_Sea |

23037 |

21055 |

1981 |

0 |

23037 |

| (7) Greenland_Sea |

127514 |

171819 |

-44304 |

79706 |

47808 |

| (8) Baffin_Bay_Gulf_of_St._Lawrence |

10485 |

27726 |

-17241 |

28385 |

-17900 |

| (9) Canadian_Archipelago |

238187 |

307540 |

-69353 |

364406 |

-126219 |

| (10) Hudson_Bay |

0 |

21905 |

-21905 |

23268 |

-23268 |

| (11) Central_Arctic |

3010000 |

2985788 |

24211 |

2813056 |

196944 |

The NH ice extent is 744k km2 or 15% below average. Most of the deficit is in the first four regions, BCE and Laptev. CAA is almost 70k km2 or 23% below its average. Other regions have smaller deficits and Central Arctic is in slight surplus.

Background: The Outlook in 2007

From Sea Ice in Canada’s Arctic: Implications for Cruise Tourism by Stewart et al. December 2007. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Although cruise travel to the Canadian Arctic has grown steadily since 1984, some commentators have suggested that growth in this sector of the tourism industry might accelerate, given the warming effects of climate change that are making formerly remote Canadian Arctic communities more accessible to cruise vessels. Using sea-ice charts from the Canadian Ice Service, we argue that Global Climate Model predictions of an ice-free Arctic as early as 2050-70 may lead to a false sense of optimism regarding the potential exploitation of all Canadian Arctic waters for tourism purposes. This is because climate warming is altering the character and distribution of sea ice, increasing the likelihood of hull-penetrating, high-latitude, multi-year ice that could cause major pitfalls for future navigation in some places in Arctic Canada. These changes may have negative implications for cruise tourism in the Canadian Arctic, and, in particular, for tourist transits through the Northwest Passage and High Arctic regions.

The most direct route through the Northwest Passage is via Viscount Melville Sound into the M’Clure Strait and around the coast of Banks Island. Unfortunately, this route is marred by difficult ice, particularly in the M’Clure Strait and in Viscount Melville Sound, as large quantities of multi-year ice enter this region from the Canadian Basin and through the Queen Elizabeth Islands.

As Figure 5 illustrates, difficult ice became particularly evident, hence problematic, as sea-ice concentration within these regions increased from 1968 to 2005; as well, significant increases in multi-year ice are present off the western coast of Banks Island as well. Howell and Yackel (2004) illustrated that ice conditions within this region during the 1969–2002 navigation seasons exhibited greater severity from 1969 to1979 than from 1991 to 2002. This variability likely is a reflection of the extreme light-ice season present in 1998(Atkinson et al., 2006), from which the region has since recovered. Cruise ships could use the Prince of Wales Strait to avoid the choke points on the western coast of Banks Island, but entry is difficult; indeed, Howell and Yackel (2004) showed virtually no change in ease of navigation from 1969 to 2002.

An alternative, longer route through the Northwest Passage passes through either Peel Sound or the Bellot Strait. The latter route potentially could avoid hazardous multi-year ice in Peel Sound, but its narrow passageway makes it unfeasible for use by larger vessels. Regardless of which route is selected, a choke point remains in the vicinity of the Victoria Strait (Fig. 5). This strait acts as a drain trap for multi-year ice that has entered the M’Clintock Channel region and gradually advances south-ward (Howell and Yackel, 2004; Howell et al., 2006). While Howell and Yackel (2004) showed slightly safer navigation conditions from 1991 to 2002 compared to 1969 to 1990, they attributed this improvement to the anomalous warm year of 1998 that removed most of the multi-year ice in the region. From 2000 to 2005, when conditions began to recover from the 1998 warming, atmospheric forcing was insufficient to break up the multi-year ice that entered the M’Clintock Channel. Instead the ice became mobile, flowing southward into the Victoria Strait as the surrounding first-year ice broke up earlier (Howell et al., 2006).

During the past 20 years, cruises gradually have become an important element of Canadian Arctic tourism, and currently there seems to be consensus about the cruise industry’s inevitable growth, especially in the vicinity of Baffin Bay. However, we have stressed the likelihood that sea-ice hazards will continue to exist and will present ongoing navigational challenges to tour operators, particularly those operating in the western regions of the Canadian Arctic.

Fast Forward to Summer of 2018: Northwest Passage Proved Impassable

August 23, 2018 . At least 22 vessels are affected and several have turned back to Greenland.

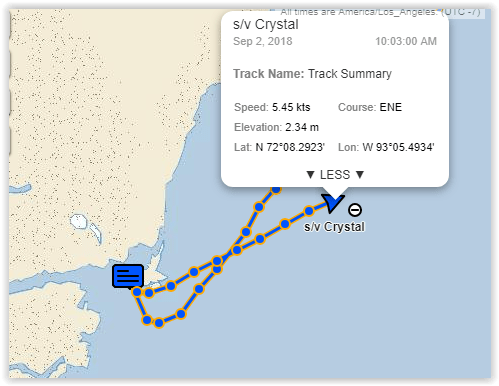

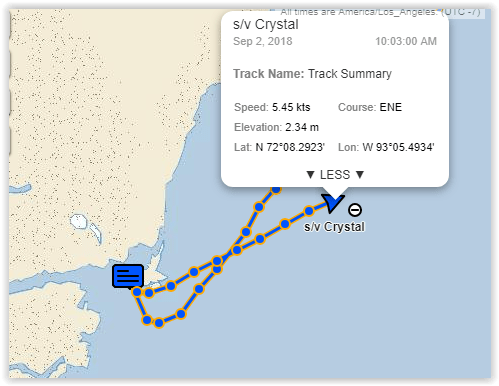

Reprinted from post on September 3, 2018: News today from the Northwest Passage blog that S/V CRYSTAL has given up after hanging around Fort Ross hoping for a storm or melting to break the ice barrier blocking their way west.

As the vessel tracker shows, they have been forced to Plan C, which is returning to Greenland and accept that the NW Passage is closed this year. The latest ice chart gave them no hope for getting through. Note yachts can sail through green (3/10), so the hope is for red to yellow to green. But that did not happen last year.

The image below shows the ice with which they were coping.

More details at NW Passage blog 20180902 S/V CRYSTAL and S/V ATKA give up and retreat back to Greenland – Score ICE 3 vs YACHTS 0

Current Situation in Canadian Arctic Archipelago

The current ice map of Queen Maude region shows the difference between 2019 and last year.

Remembering that yachts need at most 1-3/10 ice conditions (light green), it is showing Peel Sound on the left side is open now, but was the obstruction last year. Not shown but also important is open water in Barrow Strait allowing access to Peel Sound from the north. Conversely, on the top right Prince Regent Inlet is plugged at the top and impassable for now, and perhaps for the year.

As reported at the Northwest Passage Blogspot, yachts are taking the Peel Sound route this year, rather than using Prince Regent Inlet and Bellot Strait, due to ice conditions. Excerpts in italics with my bolds.

Peel Sound, With Trepidation

by Randall

August 16, 2019

Days at Sea: 262

Over the last few days, charts have shown a significant reduction in ice concentrations in Peel, but there is still ice, lots of ice. One hundred miles into the Sound from the N, there is a band of 4-6/10ths ice that is sixty-five miles long and covers both the eastern and western shores. Another one hundred miles below that is a large band of 1-3/10ths ice. Below that there is open water, but it is threatened by the heavy ice feeding in from M’Clintock Channel.

Add to this an imminent change in the weather. Long range forecasts are calling for a switch from these long-running E winds to SW winds and then strong southerlies that could scramble the current ice configuration.

Add to this a paucity of anchorages in Peel. Two of the best on the W coast are icebound. The next, False Strait, is just above Bellot Strait and 165 miles from the opening.

In the evening I reach out to the ice guide, Victor Wejer, for a consult on anchorages. Mo needs a place to hide if things go badly. I show him the areas I’ve chosen.

“This is a subject I would like to avoid,” he replies. “It is not written in stone that you must take the entirety of Peel in one go, but it is the usual way. Read the Canadian Sailing Directions. The height of Somerset Island does weird things to the wind; it can go from calm to gale in an instant. Most of what look like anchorages on the chart are just not safe.”

“As to ice,” he continues, “this is also difficult. Peel is narrow and fed from M’Clintock. Most sailboat crews fight tooth and ice pole to get through. Consider that Matt Rutherford chose Prince Regent. But for you there may not be an option. Regent will not be clear for a long time; maybe not at all this year.”

By now four boats are through Peel, below Bellot Strait and on their way to Gjoa Haven. Yellow-hulled Breskell is one of them, but it has taken her four days to transit 200 miles, and I can tell from the way Olivier writes his encouraging emails that he has his doubts about doing it solo.

MO IS THROUGH THE ICE!

by Randall

August 19, 2019

1845 local

70 32S 97 27W

Larsen Sound

The Arctic

Just a quick note to report that Mo is through the ice and sailing fast on a N wind for Cambridge Bay, 235 miles SW.

I have been pushing to get to Alioth’s position for two days. She has a busted gear box and can’t make more than three knots under power. She has been hove to at the head of our last major ice plug waiting for an escort as she’d have to sail through, a tricky business.

We’ve all been sweating bullets over this last 30 miles of ice, and for four days I’ve been underway and hand steering for 18 to 20 hours a day through 3 – 5/10ths ice to get here. Only a few hours sleep a night this last week.

As it turns out, today was a piece of cake. We saw huge ice floes the size of city blocks but with wide lanes in between. Alioth and another boat, Mandregore, sailed downwind without trouble with Mo bringing up the rear under power just in case.

June ocean air temps rose in all regions after May’s drop, resulting in the Global average back up matching June 2017. All regions dropped back down to May levels in July and are little changed in August. The temps this August are warmer than 2018 but cooler than earlier years, and also more synchronized across regions.

June ocean air temps rose in all regions after May’s drop, resulting in the Global average back up matching June 2017. All regions dropped back down to May levels in July and are little changed in August. The temps this August are warmer than 2018 but cooler than earlier years, and also more synchronized across regions.